Disease X

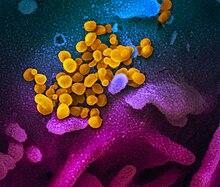

Disease X is a placeholder name that was adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February 2018 on their shortlist of blueprint priority diseases to represent a hypothetical, unknown pathogen that could cause a future epidemic.[4][5] The WHO adopted the placeholder name to ensure that their planning was sufficiently flexible to adapt to an unknown pathogen (e.g., broader vaccines and manufacturing facilities).[4][6] Director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci stated that the concept of Disease X would encourage WHO projects to focus their research efforts on entire classes of viruses (e.g., flaviviruses), instead of just individual strains (e.g., zika virus), thus improving WHO capability to respond to unforeseen strains.[7] In 2020, experts, including some of the WHO's own expert advisors, speculated that COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus strain, met the requirements to be the first Disease X.[1][2][3]

Rationale

[edit]

In May 2015, in pandemic preparations prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO was asked by member organizations to create an "R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Epidemics" to generate ideas that would reduce the time lag between the identification of viral outbreaks and the approval of vaccines/treatments, to stop the outbreaks from turning into a "public health emergency".[4][9] The focus was to be on the most serious emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) for which few preventive options were available.[9][10] A group of global experts, the "R&D Blueprint Scientific Advisory Group",[11] was assembled by the WHO to draft a shortlist of less than ten "blueprint priority diseases".[4][5][9]

Since 2015, the shortlist of EIDs has been reviewed annually and originally included widely known diseases such as Ebola and Zika which have historically caused epidemics, as well as lesser known diseases which have potential for serious outbreaks, such as SARS, Lassa fever, Marburg virus, Rift Valley fever, and Nipah virus.[5][10] Since then, COVID-19 has been added to the list.[12]

In February 2018, after the "2018 R&D Blueprint" meeting in Geneva, the WHO added Disease X to the shortlist as a placeholder for a "knowable unknown" pathogen.[4][6][13] The Disease X placeholder acknowledged the potential for a future epidemic that could be caused by an unknown pathogen, and by its inclusion, challenged the WHO to ensure their planning and capabilities were flexible enough to adapt to such an event.[5][14][15]

At the 2018 announcement of the updated shortlist of blueprint priority diseases, the WHO said: "Disease X represents the knowledge that a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease".[5][6][16] John-Arne Røttingen, of the R&D Blueprint Special Advisory Group,[8] said: "History tells us that it is likely the next big outbreak will be something we have not seen before", and "It may seem strange to be adding an 'X' but the point is to make sure we prepare and plan flexibly in terms of vaccines and diagnostic tests. We want to see 'plug and play' platforms developed which will work for any or a wide number of diseases; systems that will allow us to create countermeasures at speed".[6][10] US expert Anthony Fauci said: "WHO recognizes it must 'nimbly move' and this involves creating platform technologies", and that to develop such platforms, WHO would have to research entire classes of viruses, highlighting flaviviruses. He added: "If you develop an understanding of the commonalities of those, you can respond more rapidly".[7]

Adoption

[edit]Jonathan D. Quick, the author of End of Epidemics, described the WHO's act of naming Disease X as "wise in terms of communicating risk", saying "panic and complacency are the hallmarks of the world's response to infectious diseases, with complacency currently in the ascendance".[17] Women's Health wrote that the establishment of the term "might seem like an uncool move designed to incite panic" but that the whole purpose of including it on the list was to "get it on people's radars".[18]

Richard Hatchett of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), wrote "It might sound like science fiction, but Disease X is something we must prepare for", noting that despite the success in controlling the 2014 Western African Ebola virus epidemic, strains of the disease had returned in 2018.[19] In February 2019, CEPI announced funding of US$34 million to the German-based CureVac biopharmaceutical company to develop an "RNA Printer prototype", that CEPI said could "prepare for rapid response to unknown pathogens (i.e., Disease X)".[20]

Parallels were drawn with the efforts by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and their PREDICT program, which was designed to act as an early warning pandemic system, by sourcing and researching animal viruses in particular "hot spots" of animal-human interaction.[21]

In September 2019, The Daily Telegraph reported on how Public Health England (PHE) had launched its own investigation for a potential Disease X in the United Kingdom from the diverse range of diseases reported in their health system; they noted that 12 novel diseases and/or viruses had been recorded by PHE in the last decade.[22]

In October 2019 in New York, the WHO's Health Emergencies Program ran a "Disease X dummy run" to simulate a global pandemic by Disease X, for its 150 participants from various world health agencies and public health systems to better prepare and share ideas and observations for combatting such an eventuality.[23][24]

In March 2020, The Lancet Infectious Diseases published a paper titled "Disease X: accelerating the development of medical countermeasures for the next pandemic", which expanded the term to include Pathogen X (the pathogen that leads to Disease X), and identified areas of product development and international coordination that would help in combatting any future Disease X.[25]

In April 2020, The Daily Telegraph described remdesivir, a drug being trialed to combat COVID-19, as an anti-viral that Gilead Sciences started working on a decade previously to treat a future Disease X.[26]

In August 2023, the UK Government announced the creation of a new research center, located on the Porton Down campus, which is tasked at researching pathogens with the potential to emerge as Disease X. Live viruses will be kept in specialist containment facilities in order to develop tests and potential vaccines within 100 days in case a new threat is identified.[27]

In January 2024, during the World Economic Forum's annual meeting, Disease X was once again discussed as being a potential threat following the COVID-19 pandemic.[28][29]

Strategy

[edit]A paper published in 2022 listed the following strategies in preparation for Disease X:[30]

- steps to reduce the risk of spillover and the consequent introduction and spread of a new disease in humans;

- improving disease surveillance in humans and animals, to rapidly detect and sequence the infectious agent;

- strengthening research programs to shorten the time lag between the development and production of medical countermeasures;

- rapid implementation of pharmaceutical (e.g. vaccination) and non-pharmaceutical (e.g. social distancing) measures, to contain a large-scale epidemic;

- develop international protocols to ensure fair distribution and global coverage of drugs and vaccines.[30]

Candidates

[edit]Zoonotic viruses

[edit]On the addition of Disease X in 2018, the WHO said it could come from many sources citing hemorrhagic fevers and the more recent non-polio enterovirus.[6] However, Røttingen speculated that Disease X would be more likely to come from zoonotic transmission (an animal virus that jumps to humans), saying: "It's a natural process and it is vital that we are aware and prepare. It is probably the greatest risk".[6][10] WHO special advisor Professor Marion Koopmans, also noted that the rate at which zoonotic diseases were appearing was accelerating, saying: "The intensity of animal and human contact is becoming much greater as the world develops. This makes it more likely new diseases will emerge but also modern travel and trade make it much more likely they will spread".[10][31]

COVID-19 (2019–present)

[edit]

From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts have speculated whether COVID-19 met the criteria to be Disease X.[32][33] In early February 2020, Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli from the Wuhan Institute of Virology wrote that the first Disease X is from a coronavirus.[3] Later that month, Marion Koopmans, Head of Viroscience at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, and a member of the WHO's R&D Blueprint Special Advisory Group,[8][34] wrote in the scientific journal Cell, "Whether it will be contained or not, this outbreak is rapidly becoming the first true pandemic challenge that fits the disease X category".[2][35][36] At the same time, Peter Daszak, also a member of the WHO's R&D Blueprint, wrote in an opinion piece in The New York Times saying: "In a nutshell, Covid-19 is Disease X".[1]

Synthetic viruses/bioweapons

[edit]At the 2018 announcement of the updated shortlist of blueprint priority diseases, the media speculated that a future Disease X could be created intentionally as a biological weapon.[37] In 2018, WHO R&D Blueprint Special Advisor Group member Røttingen was questioned about the potential of Disease X to come from the ability of gene-editing technology to produce synthetic viruses (e.g., the 2017 synthesis of Orthopoxvirus in Canada was cited), which could be released through an accident or even an act of terror. Røttingen said it was unlikely that a future Disease X would originate from a synthetic virus or a bio-weapon. However, he noted the seriousness of such an event, saying, "Synthetic biology allows for the creation of deadly new viruses. It is also the case that where you have a new disease there is no resistance in the population and that means it can spread fast".[10]

Bacterial infection

[edit]In September 2019, Public Health England (PHE) reported that the increasing antibiotic resistance of bacteria, even to "last-resort" antibiotics such as carbapenems and colistin, could also turn into a potential Disease X, citing the antibiotic resistance in gonorrhea as an example.[38]

In popular culture

[edit]In 2018, the Museum of London ran an exhibition titled "Disease X: London's next epidemic?", hosted for the centenary of the Spanish flu epidemic from 1918.[39][40]

The term features in the title of several works of fiction that involve global pandemic diseases, such as Disease (2020),[41] and Disease X: The Outbreak (2019).[42]

Conspiracy theories

[edit]Disease X has become the subject of several conspiracy theories, claiming that it may be a real disease, or conceived as a biological weapon, or engineered to create a planned epidemic.[43][44]

See also

[edit]- Bioterrorism

- Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI)

- Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GloPIR-R)

- Synthetic virology

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Daszak, Peter (22 February 2020). "We Knew Disease X Was Coming. It's Here Now". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Gale, Jason (22 February 2020). "Coronavirus May Be 'Disease X' Health Experts Warned About". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Shi, Zhengli; Jiang, Shibo (2020). "The First Disease X is Caused by a Highly Transmissible Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". Virologica Sinica. 35 (3): 263–265. doi:10.1007/s12250-020-00206-5. PMC 7091198. PMID 32060789.

- ^ a b c d e "List of Blueprint priority diseases". World Health Organization. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Editorial (13 March 2018). "What is Disease X?". Economist. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

By listing Disease X, an undetermined disease, the WHO is acknowledging that outbreaks do not always come from an identified source and that, as it admits, "a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease".

- ^ a b c d e f Barns, Tom (11 March 2018). "World Health Organisation fears new 'Disease X' could cause a global pandemic". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b Scutti, Susan (12 March 2018). "World Health Organization gets ready for 'Disease X'". CNN. Archived from the original on 2018-03-12. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d "R&D Blueprint - Scientific Advisory Group members". World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (6–7 February 2018). 2018 Annual review of diseases prioritized under the Research and Development Blueprint (PDF) (Report). Geneva, Switzerland. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Nuki, Paul; Shaikh, Alanna (10 March 2018). "Scientists put on alert for deadly new pathogen – 'Disease X'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "R&D Blueprint". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts (Published 2018, revision in progress 2023)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Shaikh, Alanna; Nuki, Paul (22 July 2019). "What is 'Disease X', the mystery killer keeping scientists awake?". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Lee, Bruce Y. (March 10, 2018). "Disease X is what may Become the Biggest Infectious Threat to our World". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "WHO | List of Blueprint priority diseases". WHO. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Whittam Smith, Andreas (11 March 2018). "One hundred years on from the Spanish Flu, we are facing another major pandemic". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Gulland, Anne (15 May 2018). "Panic and complacency: how the world reacts to disease outbreaks". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Miller, Korin (12 March 2018). "Disease X Might Cause The Next Big Global Epidemic". Women's Health. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Hatchett, Richard (15 May 2018). "It might sound like science fiction, but Disease X is something we must prepare for". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Gouglas, Dimitrios; Christodoulou, Mario; Plotkin, Stanley A.; Hatchett, Richard (November 2019). "CEPI: Driving Progress Towards Epidemic Preparedness And Response". Epidemiologic Reviews. 41 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxz012. PMC 7108492. PMID 31673694.

- ^ Shute, Joe (September 2019). "Virus hunters: Meet the scientists searching for Disease X". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Gulland, Anne (11 September 2019). "Revealed: Public Health England 'hot on the trail' of Disease X". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Harriet (21 October 2019). "Disease X dummy run: World health experts prepare for a deadly pandemic and its fallout". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Hamblin, James (28 March 2020). "The Curve Is Not Flat Enough". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Simpson, Shmona; Kaufmann, Michael C.; Glozman, Vitaly; Chakrabarti, Ajoy (March 2020). "Disease X: accelerating the development of medical countermeasures for the next pandemic". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (5): e108–e115. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30123-7. PMC 7158580. PMID 32197097.

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (1 April 2020). "Drug created to fight 'Disease X' over 10 years ago will be tested in battle against coronavirus". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Adu, Aletha (6 August 2023). "New vaccine research centre in UK to help scientists prepare for 'disease X'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-31. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Singh, Simrin (2024-01-17). "World leaders are gathering to discuss Disease X. Here's what to know about the hypothetical pandemic. - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ a b Mipatrini, Daniele; Montaldo, Chiara; Bartolini, Barbara; Rezza, Giovanni; Iavicoli, Sergio; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Zumla, Alimuddin; Petersen, Eskild (2022-10-17). "'Disease X'—time to act now and prepare for the next pandemic threat". The European Journal of Public Health. 32 (6): 841–842. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckac151. ISSN 1101-1262. PMC 9713389. PMID 36250806.

- ^ Cousins, Sophie (10 May 2018). "WHO hedges its bets: the next global pandemic could be disease X". The BMJ. 361: k2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2015. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 29748222. S2CID 13668695. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Gulland, Anne (2020-01-09). "Have Chinese researchers uncovered the new disease X?". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ McKie, Robin (6 February 2020). "Coronavirus: the huge unknowns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

This hope now looks forlorn with the sudden emergence of the respiratory disease Covid-19, which has rapidly acquired most of the characteristic of a Disease X.

- ^ "R&D Blueprint: Marion Koopmans (Biography)". World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Mercer, David (25 February 2020). "Coronavirus outbreak could be feared 'Disease X', says World Health Organisation adviser". Sky News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Aaro, David (27 February 2020). "What is Disease X?". Fox News. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Cousins, Sophie (2018-05-10). "WHO hedges its bets: the next global pandemic could be disease X". BMJ. 361: k2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2015. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 29748222. S2CID 13668695. Archived from the original on 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ Campbell, Denis (11 September 2019). "Bacteria developing new ways to resist antibiotics, doctors warn". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Addley, Esther (November 2018). "Queen Victoria's mourning dress among items in Disease X exhibition". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Disease X: London's next epidemic?". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ N. J. Croft (January 2020). Disease X. Sideways Books. ASIN B081XS6FN7.

- ^ Burdette, Shannon C. (October 2019). Disease X: The Outbreak. Amazon Digital Services LLC - KDP Print US. ISBN 978-1703667806.

- ^ Graham, Freya (2024-01-15). "'Disease X' is stoking the fire of right-wing conspiracies". Metro. Archived from the original on 2024-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Swann, Sara. "PolitiFact - Conspiracy theorists falsely claim 'Disease X' is the next 'plandemic'". @politifact. Archived from the original on 2024-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

External links

[edit]- Blueprint priority diseases (Archived 2020-03-01 at the Wayback Machine)—World Health Organization (6–7 February 2018)

- Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts—World Health Organization (March 2018)

- (Video) What is Disease X—World Health Organization (16 March 2018)

- The mystery viruses far worse than flu—BBC News (November 2018)