Palladian architecture

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and the principles of formal classical architecture from ancient Greek and Roman traditions. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Palladio's interpretation of this classical architecture developed into the style known as Palladianism.

Palladianism emerged in England in the early 17th century, led by Inigo Jones, whose Queen's House at Greenwich has been described as the first English Palladian building. Its development faltered at the onset of the English Civil War. After the Stuart Restoration, the architectural landscape was dominated by the more flamboyant English Baroque. Palladianism returned to fashion after a reaction against the Baroque in the early 18th century, fuelled by the publication of a number of architectural books, including Palladio's own I quattro libri dell'architettura (The Four Books of Architecture) and Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus. Campbell's book included illustrations of Wanstead House, a building he designed on the outskirts of London and one of the largest and most influential of the early neo-Palladian houses. The movement's resurgence was championed by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, whose buildings for himself, such as Chiswick House and Burlington House, became celebrated. Burlington sponsored the career of the artist, architect and landscaper William Kent, and their joint creation, Holkham Hall in Norfolk, has been described as "the most splendid Palladian house in England".[1] By the middle of the century Palladianism had become almost the national architectural style, epitomised by Kent's Horse Guards at the centre of the nation's capital.

The Palladian style was also widely used throughout Europe, often in response to English influences. In Prussia the critic and courtier Francesco Algarotti corresponded with Burlington about his efforts to persuade Frederick the Great of the merits of the style, while Knobelsdorff's opera house in Berlin on the Unter den Linden, begun in 1741, was based on Campbell's Wanstead House. Later in the century, when the style was losing favour in Europe, Palladianism had a surge in popularity throughout the British colonies in North America. Thomas Jefferson sought out Palladian examples, which themselves drew on buildings from the time of the Roman Republic, to develop a new architectural style for the American Republic. Examples include the Hammond–Harwood House in Maryland and Jefferson's own house, Monticello, in Virginia. The Palladian style was also adopted in other British colonies, including those in the Indian subcontinent.

In the 19th century, Palladianism was overtaken in popularity by Neoclassical architecture in both Europe and in North America. By the middle of that century, both were challenged and then superseded by the Gothic Revival in the English-speaking world, whose champions such as Augustus Pugin, remembering the origins of Palladianism in ancient temples, deemed the style too pagan for true Christian worship. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Palladianism has continued to evolve as an architectural style; its pediments, symmetry and proportions are evident in the design of many modern buildings, while its inspirer is regularly cited as having been among the world's most influential architects.

Palladio's architecture

[edit]

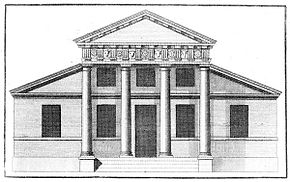

Andrea Palladio was born in Padua in 1508, the son of a stonemason.[2] He was inspired by Roman buildings, the writings of Vitruvius (80 BC), and his immediate predecessors Donato Bramante and Raphael. Palladio aspired to an architectural style that used symmetry and proportion to emulate the grandeur of classical buildings.[3] His surviving buildings are in Venice, the Veneto region, and Vicenza,[4] and include villas and churches such as the Basilica del Redentore in Venice.[5] Palladio's architectural treatises follow the approach defined by Vitruvius and his 15th-century disciple Leon Battista Alberti, who adhered to principles of classical Roman architecture based on mathematical proportions rather than the ornamental style of the Renaissance.[6] Palladio recorded and publicised his work in the 1570 four-volume illustrated study, I quattro libri dell'architettura (The Four Books of Architecture).[7]

Palladio's villas are designed to fit with their setting.[8] If on a hill, such as Villa Almerico Capra Valmarana (Villa Capra, or La Rotonda), façades were of equal value so that occupants could enjoy views in all directions.[9] Porticos were built on all sides to enable the residents to appreciate the countryside while remaining protected from the sun.[10][n 1] Palladio sometimes used a loggia as an alternative to the portico. This is most simply described as a recessed portico, or an internal single storey room with pierced walls that are open to the elements. Occasionally a loggia would be placed at second floor level over the top of another loggia, creating what was known as a double loggia.[12] Loggias were sometimes given significance in a façade by being surmounted by a pediment. Villa Godi's focal point is a loggia rather than a portico, with loggias terminating each end of the main building.[13]

Palladio would often model his villa elevations on Roman temple façades. The temple influence, often in a cruciform design, later became a trademark of his work.[14][n 2] Palladian villas are usually built with three floors: a rusticated basement or ground floor, containing the service and minor rooms; above this, the piano nobile (noble level), accessed through a portico reached by a flight of external steps, containing the principal reception and bedrooms; and lastly a low mezzanine floor with secondary bedrooms and accommodation. The proportions of each room (for example, height and width) within the villa were calculated on simple mathematical ratios like 3:4 and 4:5. The arrangement of the different rooms within the house, and the external façades, were similarly determined.[15][n 3] Earlier architects had used these formulas for balancing a single symmetrical façade; however, Palladio's designs related to the entire structure.[13] Palladio set out his views in I quattro libri dell'architettura: "beauty will result from the form and correspondence of the whole, with respect to the several parts, of the parts with regard to each other, and of these again to the whole; that the structure may appear an entire and complete body, wherein each member agrees with the other, and all necessary to compose what you intend to form."[17]

Palladio considered the dual purpose of his villas as the centres of farming estates and weekend retreats.[18] These symmetrical temple-like houses often have equally symmetrical, but low, wings, or barchessas, sweeping away from them to accommodate horses, farm animals, and agricultural stores.[19] The wings, sometimes detached and connected to the villa by colonnades, were designed not only to be functional but also to complement and accentuate the villa. Palladio did not intend them to be part of the main house, but the development of the wings to become integral parts of the main building – undertaken by Palladio's followers in the 18th century – became one of the defining characteristics of Palladianism.[20]

Venetian and Palladian windows

[edit]

Palladian, Serlian,[n 4] or Venetian windows are a trademark of Palladio's early career. There are two different versions of the motif: the simpler one is called a Venetian window, and the more elaborate a Palladian window or "Palladian motif", although this distinction is not always observed.[22]

The Venetian window has three parts: a central high round-arched opening, and two smaller rectangular openings to the sides. The side windows are topped by lintels and supported by columns.[23] This is derived from the ancient Roman triumphal arch, and was first used outside Venice by Donato Bramante and later mentioned by Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) in his seven-volume architectural book Tutte l'opere d'architettura et prospetiva (All the Works of Architecture and Perspective) expounding the ideals of Vitruvius and Roman architecture.[24] It can be used in series, but is often only used once in a façade, as at New Wardour Castle,[25] or once at each end, as on the inner façade of Burlington House (true Palladian windows).[26][n 5]

Palladio's elaboration of this, normally used in a series, places a larger or giant order in between each window, and doubles the small columns supporting the side lintels, placing the second column behind rather than beside the first. This was introduced in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice by Jacopo Sansovino (1537), and heavily adopted by Palladio in the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza,[28] where it is used on both storeys; this feature was less often copied. The openings in this elaboration are not strictly windows, as they enclose a loggia. Pilasters might replace columns, as in other contexts. Sir John Summerson suggests that the omission of the doubled columns may be allowed, but the term "Palladian motif" should be confined to cases where the larger order is present.[29]

Palladio used these elements extensively, for example in very simple form in his entrance to Villa Forni Cerato.[31] It is perhaps this extensive use of the motif in the Veneto that has given the window its alternative name of the Venetian window. Whatever the name or the origin, this form of window has become one of the most enduring features of Palladio's work seen in the later architectural styles evolved from Palladianism.[32][n 6] According to James Lees-Milne, its first appearance in Britain was in the remodelled wings of Burlington House, London, where the immediate source was in the English court architect Inigo Jones's designs for Whitehall Palace rather than drawn from Palladio himself. Lees-Milne describes the Burlington window as "the earliest example of the revived Venetian window in England".[34]

A variant, in which the motif is enclosed within a relieving blind arch that unifies the motif, is not Palladian, though Richard Boyle seems to have assumed it was so, in using a drawing in his possession showing three such features in a plain wall. Modern scholarship attributes the drawing to Vincenzo Scamozzi.[n 7] Burlington employed the motif in 1721 for an elevation of Tottenham Park in Savernake Forest for his brother-in-law Lord Bruce (since remodelled).[36][n 8] William Kent used it in his designs for the Houses of Parliament, and it appears in his executed designs for the north front of Holkham Hall.[38] Another example is Claydon House, in Buckinghamshire; the remaining fragment is one wing of what was intended to be one of two flanking wings to a vast Palladian house. The scheme was never completed and parts of what was built have since been demolished.[30]

Early Palladianism

[edit]

During the 17th century, many architects studying in Italy learned of Palladio's work, and on returning home adopted his style, leading to its widespread use across Europe and North America.[40][41] Isolated forms of Palladianism throughout the world were brought about in this way, although the style did not reach the zenith of its popularity until the 18th century.[42] An early reaction to the excesses of Baroque architecture in Venice manifested itself as a return to Palladian principles. The earliest neo-Palladians there were the exact contemporaries Domenico Rossi (1657–1737)[n 9] and Andrea Tirali (1657–1737).[n 10] Their biographer, Tommaso Temanza, proved to be the movement's most able proponent; in his writings, Palladio's visual inheritance became increasingly codified and moved towards neoclassicism.[44]

The most influential follower of Palladio was Inigo Jones, who travelled throughout Italy with the art collector Earl of Arundel in 1613–1614, annotating his copy of Palladio's treatise.[45][n 11][n 12] The "Palladianism" of Jones and his contemporaries and later followers was a style largely of façades, with the mathematical formulae dictating layout not strictly applied. A handful of country houses in England built between 1640 and 1680 are in this style.[48][49] These follow the success of Jones's Palladian designs for the Queen's House at Greenwich,[50] the first English Palladian house,[51] and the Banqueting House at Whitehall, the uncompleted royal palace in London of Charles I.[52]

Palladian designs advocated by Jones were too closely associated with the court of Charles I to survive the turmoil of the English Civil War.[53][54] Following the Stuart restoration, Jones's Palladianism was eclipsed by the Baroque designs of such architects as William Talman,[55] Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor, and Jones's pupil John Webb.[56][57]

Neo-Palladianism

[edit]English Palladian architecture

[edit]

The Baroque style proved highly popular in continental Europe, but was often viewed with suspicion in England, where it was considered "theatrical, exuberant and Catholic."[58][59] It was superseded in Britain in the first quarter of the 18th century when four books highlighted the simplicity and purity of classical architecture.[60][61] These were:

- Vitruvius Britannicus (The British Architect), published by Colen Campbell in 1715 (of which supplemental volumes appeared through the century);[62]

- I quattro libri dell'architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), by Palladio himself, translated by Giacomo Leoni and published from 1715 onwards;[62]

- De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building), by Leon Battista Alberti, translated by Giacomo Leoni and published in 1726;[63] and

- The Designs of Inigo Jones... with Some Additional Designs, published by William Kent in two volumes in 1727. A further volume, Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. William Kent was published in 1744 by the architect John Vardy, an associate of Kent.[63]

The most favoured among patrons was the four-volume Vitruvius Britannicus by Campbell,[64][65][n 13] The series contains architectural prints of British buildings inspired by the great architects from Vitruvius to Palladio; at first mainly those of Inigo Jones, but the later works contained drawings and plans by Campbell and other 18th-century architects.[67][n 14] These four books greatly contributed to Palladian architecture becoming established in 18th-century Britain.[69] Campbell and Kent became the most fashionable and sought-after architects of the era. Campbell had placed his 1715 designs for the colossal Wanstead House near to the front of Vitruvius Britannicus, immediately following the engravings of buildings by Jones and Webb, "as an exemplar of what new architecture should be".[70] On the strength of the book, Campbell was chosen as the architect for Henry Hoare I's Stourhead house.[71] Hoare's brother-in-law, William Benson, had designed Wilbury House, the earliest 18th-century Palladian house in Wiltshire, which Campbell had also illustrated in Vitruvius Britannicus.[72][n 15]

At the forefront of the new school of design was the "architect earl", Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, according to Dan Cruikshank the "man responsible for this curious elevation of Palladianism to the rank of a quasi-religion".[74][75][n 16] In 1729 he and Kent designed Chiswick House.[77][78] This house was a reinterpretation of Palladio's Villa Capra, but purified of 16th century elements and ornament.[79] This severe lack of ornamentation was to be a feature of English Palladianism.[80]

In 1734 Kent and Burlington designed Holkham Hall in Norfolk.[81][82] James Stevens Curl considers it "the most splendid Palladian house in England".[1] The main block of the house followed Palladio's dictates, but his low, often detached, wings of farm buildings were elevated in significance. Kent attached them to the design, banished the farm animals, and elevated the wings to almost the same importance as the house itself.[83] It was the development of the flanking wings that was to cause English Palladianism to evolve from being a pastiche of Palladio's original work. Wings were frequently adorned with porticos and pediments, often resembling, as at the much later Kedleston Hall, small country houses in their own right.[84][n 17]

Architectural styles evolve and change to suit the requirements of each individual client. When in 1746 the Duke of Bedford decided to rebuild Woburn Abbey, he chose the fashionable Palladian style, and selected the architect Henry Flitcroft, a protégé of Burlington.[85][86] Flitcroft's designs, while Palladian in nature, had to comply with the Duke's determination that the plan and footprint of the earlier house, originally a Cistercian monastery, be retained.[87] The central block is small, has only three bays, while the temple-like portico is merely suggested, and is closed. Two great flanking wings containing a vast suite of state rooms[88] replace the walls or colonnades which should have connected to the farm buildings;[n 18] the farm buildings terminating the structure are elevated in height to match the central block and given Palladian windows, to ensure they are seen as of Palladian design.[90] This development of the style was to be repeated in many houses and town halls in Britain over one hundred years. Often the terminating blocks would have blind porticos and pilasters themselves, competing for attention with, or complementing the central block. This was all very far removed from the designs of Palladio two hundred years earlier. Falling from favour during the Victorian era, the approach was revived by Sir Aston Webb for his refacing of Buckingham Palace in 1913.[91][n 19]

The villa tradition continued throughout the late 18th century, particularly in the suburbs around London. Sir William Chambers built many examples, such as Parkstead House.[94] But the grander English Palladian houses were no longer the small but exquisite weekend retreats that their Italian counterparts were intended as. They had become "power houses", in Sir John Summerson's words, the symbolic centres of the triumph and dominance of the Whig Oligarchy who ruled Britain unchallenged for some fifty years after the death of Queen Anne.[95][96] Summerson thought Kent's Horse Guards on Whitehall epitomised "the establishment of Palladianism as the official style of Great Britain".[63] As the style peaked, thoughts of mathematical proportion were swept away. Rather than square houses with supporting wings, these buildings had the length of the façade as their major consideration: long houses often only one room deep were deliberately deceitful in giving a false impression of size.[97]

Irish Palladian architecture

[edit]

During the Palladian revival period in Ireland, even modest mansions were cast in a neo-Palladian mould. Irish Palladian architecture subtly differs from the England style. While adhering as in other countries to the basic ideals of Palladio, it is often truer to them.[98] In Ireland, Palladianism became political; both the original and the present Irish parliaments in Dublin occupy Palladian buildings.[99][n 20]

The Irish architect Sir Edward Lovett Pearce (1699–1733) became a leading advocate.[101] He was a cousin of Sir John Vanbrugh, and originally one of his pupils. He rejected the Baroque style, and spent three years studying architecture in France and Italy before returning to Ireland. His most important Palladian work is the former Irish Houses of Parliament in Dublin.[102] Christine Casey, in her 2005 volume Dublin, in the Pevsner Buildings of Ireland series, considers the building, "arguably the most accomplished public set-piece of the Palladian style in [Britain]".[103] Pearce was a prolific architect who went on to design the southern façade of Drumcondra House in 1725[104] and Summerhill House in 1731,[105] which was completed after his death by Richard Cassels.[106] Pearce also oversaw the building of Castletown House near Dublin, designed by the Italian architect Alessandro Galilei (1691–1737).[98] It is perhaps the only Palladian house in Ireland built with Palladio's mathematical ratios, and one of a number of Irish mansions which inspired the design of the White House in Washington, D.C.[107]

Other examples include Russborough, designed by Richard Cassels,[108] who also designed the Palladian Rotunda Hospital in Dublin and Florence Court in County Fermanagh.[97] Irish Palladian country houses often feature robust Rococo plasterwork – an Irish specialty which was frequently executed by the Lafranchini brothers and far more flamboyant than the interiors of their contemporaries in England.[109] In the 20th century, during and following the Irish War of Independence and the subsequent civil war, large numbers of Irish country houses, including some fine Palladian examples such as Woodstock House,[110] were abandoned to ruin or destroyed.[111][112][113][n 21]

North American Palladian architecture

[edit]

Palladio's influence in North America is evident almost from its first architect-designed buildings.[n 22] The Irish philosopher George Berkeley, who may be America's first recorded Palladian, bought a large farmhouse in Middletown, Rhode Island, in the late 1720s, and added a Palladian doorcase derived from Kent's Designs of Inigo Jones (1727), which he may have brought with him from London.[119] Palladio's work was included in the library of a thousand volumes amassed for Yale College.[120] Peter Harrison's 1749 designs for the Redwood Library in Newport, Rhode Island, borrow directly from Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura, while his plan for the Newport Brick Market, conceived a decade later, is also Palladian.[121]

Two colonial period houses that can be definitively attributed to designs from I quattro libri dell'architettura are the Hammond-Harwood House (1774) in Annapolis, Maryland, and Thomas Jefferson's first Monticello (1770). Hammond-Harwood was designed by the architect William Buckland in 1773–1774 for the wealthy farmer Matthias Hammond of Anne Arundel County, Maryland. The design source is the Villa Pisani,[122] and that for the first Monticello, the Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese.[123] Both are taken from Book II, Chapter XIV of I quattro libri dell'architettura.[124] Jefferson later made substantial alterations to Monticello, known as the second Monticello (1802–1809),[125] making the Hammond-Harwood House the only remaining house in North America modelled directly on a Palladian design.[126][127]

Jefferson referred to I quattro libri dell'architettura as his bible.[n 23] Although a statesman, his passion was architecture,[130] and he developed an intense appreciation of Palladio's architectural concepts; his designs for the James Barbour Barboursville estate, the Virginia State Capitol, and the University of Virginia campus were all based on illustrations from Palladio's book.[131][132][n 24] Realising the political significance of ancient Roman architecture to the fledgling American Republic, Jefferson designed his civic buildings, such as The Rotunda,[134] in the Palladian style, echoing in his buildings for the new republic examples from the old.[135]

In Virginia and the Carolinas, the Palladian style is found in numerous plantation houses, such as Stratford Hall,[136] Westover Plantation[137] and Drayton Hall.[138] Westover's north and south entrances, made of imported English Portland stone, were patterned after a plate in William Salmon's Palladio Londinensis (1734).[139][n 25] The distinctive feature of Drayton Hall, its two-storey portico, was derived from Palladio,[141] as was Mount Airy, in Richmond County, Virginia, built in 1758–1762.[142] A particular feature of American Palladianism was the re-emergence of the great portico which, as in Italy, fulfilled the need of protection from the sun; the portico in various forms and size became a dominant feature of American colonial architecture. In the north European countries the portico had become a mere symbol, often closed, or merely hinted at in the design by pilasters, and sometimes in very late examples of English Palladianism adapted to become a porte-cochère; in America, the Palladian portico regained its full glory.[143]

The White House in Washington, D.C., was inspired by Irish Palladianism.[107] Its architect James Hoban, who built the executive mansion between 1792 and 1800, was born in Callan, County Kilkenny, in 1762, the son of tenant farmers on the estate of Desart Court, a Palladian House designed by Pearce.[144] He studied architecture in Dublin, where Leinster House (built c. 1747) was one of the finest Palladian buildings of the time.[107] Both Cassel's Leinster House and James Wyatt's Castle Coole have been cited as Hoban's inspirations for the White House but the more neoclassical design of that building, particularly of the South façade which closely resembles Wyatt's 1790 design for Castle Coole, suggests that Coole is perhaps the more direct progenitor. The architectural historian Gervase Jackson-Stops describes Castle Coole as "a culmination of the Palladian traditions, yet strictly neoclassical in its chaste ornament and noble austerity",[145] while Alistair Rowan, in his 1979 volume, North West Ulster, of the Buildings of Ireland series, suggests that, at Coole, Wyatt designed a building, "more massy, more masculine and more totally liberated from Palladian practice than anything he had done before."[146]

Because of its later development, Palladian architecture in Canada is rarer. In her 1984 study, Palladian Style in Canadian Architecture, Nathalie Clerk notes its particular impact on public architecture, as opposed to the private houses in the United States.[147] One example of historical note is the Nova Scotia Legislature building, completed in 1819.[148] Another example is Government House in St. John's, Newfoundland.[149]

Palladianism elsewhere

[edit]

The rise of neo-Palladianism in England contributed to its adoption in Prussia. Count Francesco Algarotti wrote to Lord Burlington to inform him that he was recommending to Frederick the Great the adoption in his own country of the architectural style Burlington had introduced in England.[150] By 1741, Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff had already begun construction of the Berlin Opera House on the Unter den Linden, based on Campbell's Wanstead House.[151]

Palladianism was particularly adopted in areas under British colonial rule. Examples can be seen in the Indian subcontinent; the Raj Bhavan, Kolkata (formerly Government House) was modelled on Kedleston Hall,[152] while the architectural historian Pilar Maria Guerrieri identifies its influences in Lutyens' Delhi.[153] In South Africa, Federico Freschi notes the "Tuscan colonnades and Palladian windows" of Herbert Baker's Union Buildings.[154]

Legacy

[edit]

By the 1770s, British architects such as Robert Adam and William Chambers were in high demand, but were now drawing on a wide variety of classical sources, including from ancient Greece, so much so that their forms of architecture became defined as neoclassical rather than Palladian.[156][157] In Europe, the Palladian revival ended by the close of the 18th century. In the 19th century, proponents of the Gothic Revival such as Augustus Pugin, remembering the origins of Palladianism in ancient temples, considered it pagan, and unsuited to Anglican and Anglo-Catholic worship.[158][159][n 26] In North America, Palladianism lingered a little longer; Thomas Jefferson's floor plans and elevations owe a great deal to Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura.[161]

The term Palladian is often misused in modern discourse and tends to be used to describe buildings with any classical pretensions.[162][163] There was a revival of a more serious Palladian approach in the 20th century when Colin Rowe, an influential architectural theorist, published his essay, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa, (1947), in which he drew links between the compositional "rules" in Palladio's villas and Le Corbusier's villas at Poissy and Garches.[164][165] Suzanne Walters' article The Two Faces of Modernism suggests a continuing influence of Palladio's ideas on architects of the 20th century.[166][n 27] In the 21st century Palladio's name regularly appears among the world's most influential architects.[168][169][170] In England, Raymond Erith (1904–1973) drew on Palladian inspirations, and was followed in this by his pupil, subsequently partner, Quinlan Terry.[171] Their work, and that of others,[155] led the architectural historian John Martin Robinson to suggest that "the Quattro Libri continues as the fountainhead of at least one strand in the English country house tradition."[172][n 28][n 29]

See also

[edit]- City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto

- New Classical architecture

- Giacomo Quarenghi

- Riviera del Brenta

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Palladio's description of the Villa Capra includes the commentary; "One enjoys the most beautiful views on all sides and for this reason, porticos have been built on all four sides."[11]

- ^ Giles Worsley, in his study Inigo Jones and the European Classicist Tradition, writes; "The portico is so strongly associated today with the country house, and specifically with Palladio's villas, it is easy to forget that, outside of the Veneto, it was principally associated with religious buildings until the late seventeenth century".[10]

- ^ Wundram and Pape describe Palladio's approach in the chapter on the Villa Capra in their 2004 study, Palladio: The Complete Buildings; "The proportions and principles become clear in the ground-plan with positively mathematical precision. The porticos take up half the width of the cubical central building. The column entrance halls and flights of steps each correspond to half the depth of the core of the building. In other words, the sum of the four porticos and flights of steps covers the same area as the main building."[16]

- ^ After Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554), an architect and illustrator whose L'Architetturra was a model for Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura.[21]

- ^ The architectural historian Timothy Mowl notes that the placing of the Venetian windows in each end bay was, in fact, "something Palladio never did."[27]

- ^ A notable example in America is the Palladian window set into the north front of Mount Vernon, George Washington's home in Virginia. The centrepiece of the New Room, and installed during Washington's second rebuilding, the window draws heavily on a design from Batty Langley's City and Country Builder's and Workman's Treasury of Designs, published in 1750.[33]

- ^ Inigo Jones met Scamozzi in Venice in 1613–1614 and the former's acerbic criticisms of the latter, "in this as in most things Scamozzi errs", have been much analysed by architectural historians. Nonetheless, Giles Worsley notes the large number of books and drawings by Scamozzi Jones held in his library, and their considerable influence on his work.[35]

- ^ A design by Burlington for a Kitchen block at Tottenham draws inspiration very directly from a Palladio design for the Villa Valmarana (Vigardolo).[37]

- ^ Rossi built the new façade for the rebuilt Sant'Eustachio, known in Venice as San Stae, 1709, which was among the most sober in a competition that was commemorated with engravings of the submitted designs, and he rebuilt Ca' Corner della Regina, 1724–1727.[43]

- ^ His façade of San Vidal is a faithful restatement of Palladio's San Francesco della Vigna and his masterwork is Tolentini, Venice (1706–1714).[43]

- ^ Inigo Jones's annotated copy of I quattro libri dell'architettura is held in the library of Worcester College, Oxford. Summerson described it as "a document fraught with great significance for English architecture."[46]

- ^ Jones travelled as far south as Naples where he closely studied the church of San Paolo Maggiore. Palladio had written about, and illustrated, this church which, before severe damage in an earthquake in 1688, "looked like the Roman temple it essentially was".[47]

- ^ Modern scholarship suggests that Campbell's talents as a copyist and self-publicist exceeded his architectural ability. John Harris, in his 1995 catalogue The Palladian Revival, accuses Campbell of "outrageous plagiari[sm]".[66]

- ^ Howard Colvin writes; "It was a book with a message, the superiority of ‘antique simplicity’ over the ‘affected and licentious’ forms of the Baroque".[68]

- ^ In 1718 William Benson manoeuvred Sir Christopher Wren out of his post of Surveyor of the King's Works, but held the job for less than a year; John Summerson notes, "Benson proved his incompetence with surprising promptitude and resigned in 1719".[73]

- ^ James Stevens Curl considers Burlington, "one of the most potent influences on the development of English architecture in its entire history".[76]

- ^ At Holkham, the four wings contain a chapel, a kitchen, a guest wing and a private family wing.[82]

- ^ The architectural historian Mark Girouard, in his work, Life In The English Country House, notes that the arrangement developed by Palladio with the wings of the villa containing farm buildings was never followed in England. Although there are examples in Ireland and in North America, such "a close connection between house and farm was entirely at variance with the English tradition".[89]

- ^ Sir Aston Webb drew inspiration for his Buckingham Palace east frontage from the south front of Lyme Park, Cheshire by Giacomo Leoni (1686–1746).[92][93]

- ^ So much of Dublin was built in the 18th century that it set a Georgian stamp on the city; however, due to poor planning and poverty, Dublin was until recently one of the few cities where fine 18th-century housing could be seen in ruinous condition.[100]

- ^ Kilboy House, in Dolla, County Tipperary is a Palladian mansion that first burnt down in 1922. The reconstructed house was again destroyed by fire in 2005[114] and was rebuilt in a Palladian style by Quinlan Terry and his son Francis[115] for Tony Ryan, the founder of Ryanair.[116] Country Life described Kilboy as "the greatest new house in Europe".[117][118]

- ^ A brief survey is Robert Tavernor, "Anglo-Palladianism and the birth of a new nation" in Palladio and Palladianism, (1991), pp.181–209; Walter Muir Whitehill, Palladio in America, (1978) is still the standard work.

- ^ An exhibition, Jefferson and Palladio: Constructing a New World was held at the Palladio Museum in Vicenza in 2015–2016. The exhibition was dedicated to Mario Valmarana, Professor of Architecture at the University of Virginia and a descendant of the family who commissioned Palladio to design the Villa Valmarana.[128][129]

- ^ In a letter to James Oldham, dated Christmas Eve 1804, Jefferson wrote, "there never was a Palladio here even in private hands until I brought one. I send you my portable edition. It contains only the 1st book on the orders, which is the essential part".[133]

- ^ Specifically, both doors seem to have been derived from plates XXV and XXVI of Palladio Londinensis, a builder's guide first published in London in 1734, the year when the doorways may have been installed.[140]

- ^ In Contrasts, his trumpet blast against Classical architectural forms, Pugin quotes approvingly from Charles Forbes René de Montalembert; "modern Catholics have formed the types of their churches from the detestable models of pagan error, raising temples in imitation of the Parthenon and the Pantheon, representing the Eternal Father under the semblance of Jupiter, the blessed Virgin as a draped Venus, saints as amorous nymphs and angels in the form of Cupids."[160]

- ^ Examples include Peter Zumthor's Secular Retreat in Devon, a "countryside villa in the tradition of Andrea Palladio",[167] and Julian Bicknell's Henbury Hall in Cheshire.[155]

- ^ The Palladian inspiration for modern British architects has not always been appreciated. In an article in Apollo entitled "The curse of Palladio", the critic Gavin Stamp critiqued Erith and Terry's work as "photocopy-Palladian, classical details stuck onto dull boxes".[173]

- ^ The continuing Palladian influence in North America has also drawn criticism. The critic Stephen Bayley, in a review of the 2009 Palladio exhibition at the Royal Academy, wrote of "American realtors describ(ing) any dire Miami McMansion with a classical portico and the odd volute as Palladian."[174]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Curl 2016, p. 409.

- ^ Tavernor 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 549.

- ^ "City of Vincenza and the Palladian villas of the Veneto". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Wundram & Pape 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Wittkower 1988, p. 31.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 551.

- ^ Wundram & Pape 2004, p. 240.

- ^ Wundram & Pape 2004, p. 186.

- ^ a b Worsley 2007, p. 129.

- ^ Kruft 1994, p. 90.

- ^ "Palazzo Chiericati". Palladio Museum. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ a b Copplestone 1963, p. 251.

- ^ Tavernor 1991, p. 77.

- ^ Wassell, Stephen R. (19 January 2004). "The Mathematics of Palladio's Villas" (PDF). Nexus Network Journal. doi:10.1007/s00004-998-0011-3. S2CID 119876036. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Wundram & Pape 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Matuke, Samantha (12 May 2016). "Mathematical Beauty in Renaissance Architecture" (PDF). Renaissance Architecture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Kerley, Paul (10 September 2015). "Palladio: The architect who inspired our love of columns". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ O'Brien & Guinness 1993, p. 52.

- ^ Copplestone 1963, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 696.

- ^ "Seven Palladian windows". RIBA Journal. 7 September 2014. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Summerson 1981, p. 134.

- ^ Wittkower 1974, p. 156.

- ^ "Wardour Castle". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Royal Academy including Burlington House and Galleries and Royal Academy Schools Buildings". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Mowl 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Summerson 1981, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Summerson 1981, p. 130.

- ^ a b "Claydon House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Wundram & Pape 2004, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Constant 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Brandt, Lydia Mattice. "Palladian Window". Mount Vernon Estate. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Lees-Milne 1986, p. 100.

- ^ Worsley 2007, p. 99.

- ^ Bold 1988, pp. 140–144.

- ^ Harris 1995, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Lees-Milne 1986, p. 133.

- ^ "Queen's House". Royal Museums Greenwich. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Ackerman 1991, p. 80.

- ^ "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Copplestone 1963, p. 252.

- ^ a b Howard & Quill 2002, p. 238.

- ^ Tavernor 1991, p. 112.

- ^ Pevsner 1960, p. 516.

- ^ Summerson 1953, p. 66.

- ^ Chaney 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Bold 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Bold 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Whinney 1970, pp. 33–35.

- ^ "Designing the Queen's House". Royal Museums Greenwich. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Copplestone 1963, p. 280.

- ^ Bold 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Whyte, William. "What is Palladianism?". National Trust. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Colvin 1978, p. 803.

- ^ Copplestone 1963, p. 281.

- ^ "Introduction to Georgian Architecture". The Georgian Group. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (10 September 2011). "English baroque architecture: seventy years of excess". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Summerson 1953, pp. 295–297.

- ^ Cruikshank 1985, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Summerson 1953, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Summerson 1953, p. 208.

- ^ Summerson 1953, pp. 297–308.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 140.

- ^ Harris 1995, p. 15.

- ^ "Palladianism – an introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Colvin 1978, p. 182.

- ^ Wainright, Oliver (11 September 2015). "Why Palladio is the world's favourite 16th-century architect". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Vitruvius Britannicus, or The British Architect, Volume I". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Stourhead House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Orbach, Pevsner & Cherry 2021, p. 784.

- ^ Summerson 1953, p. 170.

- ^ Cruikshank 1985, p. 8.

- ^ Summerson 1953, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 128.

- ^ "History of Chiswick House and Gardens". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Summerson 1953, pp. 309–313.

- ^ Yarwood 1970, p. 104.

- ^ "Palladianism – An Introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Bold 1988, p. 141.

- ^ a b "Holkham Hall". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Summerson 1953, p. 194.

- ^ "Kedleston Hall". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Woburn Abbey: Official list entry". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Henry Flitcroft – 'Burlington Harry'". Twickenham Museum. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ O'Brien & Pevsner 2014, p. 331.

- ^ Jenkins 2003, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Girouard 1980, p. 151.

- ^ O'Brien & Pevsner 2014, p. 332.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2006, p. 94.

- ^ "Lyme Park, Cheshire". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Lyme Park (Lyme Hall)". DiCamillo. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Worsley 1996, p. 82.

- ^ Ruhl 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Spens, Michael (14 February 2009). "Andrea Palladio and the New Spirit in Architecture". Studio International Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ a b Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 70.

- ^ a b Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 55.

- ^ "Palladian style (1720–1770)". Dublin Civic Trust. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Casey 2005, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 59.

- ^ Casey 2005, p. 380.

- ^ "Sir Edward Lovett Pearce – Drumcondra House, Dublin". Dictionary of Irish Architects 1720–1940. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Summerhill, Co. Meath". Sir John Soane's Museum. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Sheridan, Pat (2014). "Sir Edward Lovett Pearce 1699–1733: the Palladian architect and his buildings". Dublin Historical Record. 67 (2): 19–25. JSTOR 24615990.

- ^ a b c Fedderly, Eva (11 March 2021). "Meet the Man who Designed and Built the White House". Architectural Digest. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ MacDonnell 2002, p. 77.

- ^ O'Brien & Guinness 1993, pp. 246–247.

- ^ "Palladian architecture". Ask About Ireland. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ MacDonnell 2002, Introduction.

- ^ Mount, Harry (16 March 2019). "Irish Ruins". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Dooley, Terence (28 May 2022). "The Power of Ruins". Centre for the Study of Historic Irish Houses and Estates (CSHIHE). Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Kilboy House". National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Kilboy House". Francis Terry and Associates. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Gleeson, Peter (6 April 2006). "Ryans to rebuild 18th century mansion". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Stamp, Agnes (7 September 2016). "Contents". Country Life. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Kilboy House". Garland Consultants. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Gaustad 1979, p. 70.

- ^ Gaustad 1979, p. 86.

- ^ "Building America". The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 December 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Palladio and English-American Palladianism". The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Hawthorne, Christopher (30 November 2008). "A very fine Italian House". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Benson, Sarah B. "Hammond-Harwood House Architectural Tour" (PDF). Hammond-Harwood House Museum. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Monticello House and Garden FAQs". Monticello.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Hammond-Harwood House". Society of Architectural Historians. 17 July 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "The Palladian Connection". Hammond-Harwood House. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Jefferson and Palladio: Constructing a New World". Palladio Museum. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Villa Valmarana, Lisiera". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, pp. 139–141.

- ^ De Witt & Piper 2019, p. 1.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson's Library – The architecture of A. Palladio". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Extract from Thomas Jefferson to James Oldham". Monticello.org. 24 December 1804. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Farber & Reed 1980, p. 107.

- ^ Tavernor 1991, p. 188.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 121.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 127.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, p. 84.

- ^ Severens 1981, p. 37.

- ^ Morrison 1952, p. 340.

- ^ Severens 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Guinness & Sadler 1976, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Loth, Calder (10 August 2010). "Palladio and his legacy – a transatlantic journey". National Building Museum. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Co. Kilkenney, Desart Court". Dictionary of Irish Architects. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Jackson-Stops 1990, p. 106.

- ^ Rowan 1979, p. 176.

- ^ Clerk 1984, p. 5.

- ^ "Province House National Historic Site of Canada". Canadian Register of Historic Places. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Government House National Historic Site of Canada". Canadian Register of Historic Places. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Lees-Milne 1986, p. 120.

- ^ Weekes, Ray. "The Architecture of Wansted House" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Metcalf 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Guerrieri 2021, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Freschi 2017, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Brittain-Catlin, Timothy (19 December 2019). "When Palladio came to Cheshire – in the 1980s". Apollo. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Curl 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 161.

- ^ Frampton 2001, p. 36.

- ^ "Georgians: Architecture". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Charlesworth 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Curl 2016, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Lofgren, Mike (17 January 2022). "The growing blight of infill McMansions". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Bayley, Stephen (1 February 2009). "Endlessly copied but never bettered". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Rowe, Colin (31 March 1947). "The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa, Palladio and Le Corbusier compared". Architectural Review. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 658.

- ^ Waters, Suzanne. "The Two Faces of Modernism". RIBA. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Frearson, Amy (29 October 2018). "Peter Zumthor completes Devon countryside villa in the tradition of Andrea Palladio". Dezeen. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Glancy, Jonathan (9 January 2009). "The stonecutter who shook the world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Andrea Palladio: the man who made ancient modern". George Washington University. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Kerley, Paul (10 September 2015). "Palladio: The architect who inspired our love of columns". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Neville, Flora (23 March 2017). "Interview with Quinlan Terry". Spears. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Robinson 1983, p. 173.

- ^ Stamp, Gavin (November 2004). "The curse of Palladio". Apollo. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Bayley, Stephen (1 February 2009). "Endlessly copied, but never bettered". The Observer. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Ackerman, James S. (1991). Palladio. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-141-93638-3. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Bold, John (1988). Wilton House and English Palladianism. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-113-00022-7.

- Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin. Buildings of Ireland. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10923-8.

- Chaney, Edward (2006). George Berkeley's Grand Tours: The Immaterialist as Connoisseur of Art and Architecture. Vol. The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations Since the Renaissance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-714-64577-3. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Charlesworth, Michael (2002). The Gothic Revival 1720–1870 – Literary Sources and Documents: Gothic and National Architecture. Vol. 3. Robertsbridge, East Sussex: Helm Information. ISBN 978-1-873-40367-9.

- Clerk, Nathalie (1984). Palladian Style in Canadian Architecture (PDF). Ottawa, Canada: Parks Canada. ISBN 978-0-660-11530-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- Colvin, Howard (1978). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects. London: John Murray. OCLC 757798516.

- Constant, Caroline (1993). The Palladio Guide. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-878-27185-3.

- Copplestone, Trewin (1963). World Architecture. London: Hamlyn. OCLC 473368368.

- Cruikshank, Dan (1985). A guide to Georgian buildings of Britain and Ireland. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson (with the National Trust and Irish Georgian Society). ISBN 978-0-297-78610-8.

- Curl, James Stevens (2016). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-67499-2.

- De Witt, Lloyd; Corey, Piper (2019). Thomas Jefferson Architect. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24620-9. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Farber, Joseph C.; Reed, Henry Hope (1980). Palladio's Architecture and Its Influence: A Photographic Guide. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-23922-4.

- Frampton, Kenneth (2001). Studies in Tectonic Culture. Cambridge, US: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-06173-5.

- Freschi, Federico (2017). "Poetry in Pidgin – Notes on the Persistence of Classicism in the Architecture of Johannesburg". In Grant Parker (ed.). South Africa, Greece, Rome – Classical Confrontations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10081-7.

- Gaustad, Edwin (1979). George Berkeley in America. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02394-7.

- Girouard, Mark (1980). Life In The English Country House. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-05406-4.

- Guerrieri, Pilar Maria (December 2021). "Migrating architectures: Palladio's legacy from Calcutta to New Delhi". City, Territory and Architecture. 8 (1). doi:10.1186/s40410-021-00135-0. hdl:11311/1261786. S2CID 235307212. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- Guinness, Desmond; Sadler, Julius Trousdale (1976). The Palladian Style in England, Ireland and America. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-34067-7.

- Harris, John (1995). The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05983-0.

- Howard, Deborah; Quill, Sarah (2002). The Architectural history of Venice. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09028-4.

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. London: Pavilion Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-851-45383-2.

- Jenkins, Simon (2003). England's Thousand Best Houses. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-713-99596-1.

- Kruft, Hanno-Walter (1994). A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Princeton, US: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-568-98010-2. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Lees-Milne, James (1986). The Earls of Creation. London: Century Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-712-69464-3.

- MacDonnell, Randal (2002). The Lost Houses of Ireland. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84301-6.

- Metcalf, Thomas R. (1989). An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain's Raj. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-15419-7.

- Morrison, Hugh (1952). American's First Architecture: From the First Colonial Settlements to the National Period. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 1152916624.

- Mowl, Timothy (2006). William Kent: Architect, Designer, Opportunist. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-07350-9.

- O'Brien, Charles; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2014). Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire and Peterborough. The Buildings of England. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20821-4.

- O'Brien, Jacqueline; Guinness, Desmond (1993). Great Irish Houses and Castles. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-83236-2.

- Orbach, Julian; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2021). Wiltshire. The Buildings of England. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25120-3.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1960). An Outline of European Architecture. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. OCLC 154230727.

- Robinson, John Martin (1983). The Latest Country Houses. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-370-30562-2.

- Rowan, Alistair (1979). North West Ulster. The Buildings of Ireland. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-300-09667-5.

- Ruhl, Carsten (2011). Palladianism: From the Italian Villa to International Architecture. Mainz, Germany: Institute of European History. OCLC 1184498677. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- Severens, Kenneth (1981). Southern Architecture: 350 Years of Distinctive American Buildings. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-20692-7.

- Summerson, John (1953). Architecture in Britain: 1530–1830. Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. OCLC 1195758004.

- — (1981). The Classical Language of Architecture. World of Art. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20177-0.

- Sutcliffe, Anthony (2006). London: An Architectural History. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11006-7.

- Tavernor, Robert (1991). Palladio and Palladianism. World of Art. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20242-5.

- Whinney, Margaret (1970). Howard Colvin; John Harris (eds.). A Unknown Design for a Villa by Inigo Jones. Vol. The Country Seat: Studies Presented to Sir John Summerson. London: Penguin Books. OCLC 1160730033.

- Wittkower, Rudolf (1974). Palladio and English Palladianism. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 462688249.

- — (1988) [1949]. Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (PDF). London: Academy Editions. ISBN 978-0-471-97763-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- Worsley, Giles (1996). "The Villa and the Classical Country Houses". In John Harris; Michael Snodin (eds.). Sir William Chambers: Architect to George III. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06940-2. OCLC 750912646.

- — (2007). Inigo Jones and the European Classicist Tradition. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11729-5.

- Wundram, Manfred; Pape, Thomas (2004). Palladio: The Complete Buildings. Koln, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-822-83200-4.

- Yarwood, Doreen (1970). Robert Adam. New York: Scribner. OCLC 90417.

External links

[edit]- Center for Palladian Studies in America

- Inigo Jones document collection at Worcester College, Oxford

- International centre for the study of the architecture of Andrea Palladio (CISA) (in English and Italian)

- Thomas Jefferson's architecture Archived 6 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Article on Palladian architecture in colonial Singapore, published by the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning