Pacific Guano Company

Pacific Guano Company (also known as Pacific Guano Company of Boston; 1861–1889) was an American company chartered by the State of Massachusetts, with a capital of US$1,000,000. Its business office was located in Boston. Its stockholders were residents of Massachusetts, New York, Maryland, South Carolina, and Georgia. Its works were located at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and at Charleston, South Carolina.[1] It manufactured fertilizer from guano imported from islands in the Pacific Ocean, the Caribbean, and off the coast of South Carolina.[2] In its day, the Pacific Guano Company was the largest manufacturer of superphosphates in the U.S., using fish and the Charleston phosphate for the manufacture of their superphosphate, the "Soluble Pacific Guano".[3]

History

[edit]

This company was established in 1861 by a number of ship-owners in search of business for their unemployed vessels. Having purchased Howland Island in the Southern Pacific, where there was a rich deposit of bird guano, they established their business on Spectacle Island, in Boston Harbor, and here they carried their guano, and, having dried it in the vats of the deserted salt-works, put it up in bags for the market. After a time, it was suggested that the guano might be improved by the admixture of refuse fish, and that the ammonia lost by exposure to the weather might thus be replaced. In this way, the use of menhaden chum, already well known as a manure, was introduced into the manufacture.[2]

In 1863, the works were removed to Woods Hole, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, with the intention of capturing the fish needed, and after extracting the oil, applying the pumice to the manufacture of guano.[2] By 1879, the plant had discontinued the fisheries and oil pressing branch of business.[3]

To this end an extensive outfit of vessels and nets was obtained and a force of men employed. The location, however, proved to be unfavorable, and after five years’ trial the fishery project was abandoned. At this point, however, there was little difficulty in procuring the necessary supply of fish-serap from the oil-works on Narragansett Bay and Long Island Sound.[2]

About 1866, the supply of guano on Howland's Island having become nearly exhausted, its place was gradually supplied by the phosphate of lime brought from Swan Island, and two years later by the South Carolina phosphates.[2]

The use of the bird-guano, from which the company originally took its name, was later entirely discontinued, though for some years, it was the custom to add a small percentage of that substance. The mineral phosphates were found to supply its place satisfactorily.[2]

Factories

[edit]

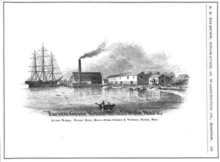

The Boston-based company had two factories: that at Woods Hole, Massachusetts and another near Charleston, South Carolina. The capacity of the latter was about two-thirds of the former, although the working force was about the same.

That at Woods Hole, which was considered to be the representative establishment, was situated on Long Neck peninsula (now known as Penzance Point),[4] about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) northwest of the village. The factory buildings were very extensive, covering nearly 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land, and were used exclusively in the manufacture of the guano, and sulphuric acid used in its development, and for storing the raw materials.[2]

A group of about 85 men were employed, one-third of whom were engaged in loading and unloading wharf-work, one-third in manufacture, and one-third in packing for shipment. At one time, as many as 125 men were employed, but the introduction of labor-saving machinery rendered a considerable reduction of the force practicable, while at the same time, the working capacity of the factory was largely increased.[2]

A steam-engine of 120 horse-power was used; also two small hoisting engines for loading and discharging cargoes. The ingredients of manufacture were few and simple, viz: fish-scrap, mineral phosphate of lime, sulphuric acid, and incidentally kainite, and sometimes common salt.[2]

The average annual purchase of scrap amounted to not far from 10,000 tons. It was stored in bulk in great wooden sheds, and was sometimes retained a long time before it could be used. By 1875, a large quantity remained over from the previous year. The storehouses covered an area of 16,640 square feet (1,546 m2), and the scrap was stowed to the depth of 15 feet (4.6 m), giving a storage space of 159,600 cubic feet.[2]

The mineral phosphate was obtained chiefly from South Carolina, from the Ashley and Cooper Rivers and from Chisholm's Island in Bull River, near Saint Helena Sound. The company owned Swan Island, situated in the Caribbean Sea, about 290 miles (470 km) off Jamaica, and the phosphate of lime was obtained from that point until 1866 or 1867, when the reopening of the south gave access to the Charleston beds. The company used a considerable quantity of the rock from Navassa, a small island lying between Cuba and Santo Domingo, a reddish deposit, rich in phosphate of lime. This deposit was estimated to contain on the average 72 per cent of phosphate of lime, while the brown deposit from Saint Helena Sound, technically known as "marshrock", contained 60 per cent, and the yellow "land-rock", from the vicinity of Charleston, only 50. About 12,000 tons of this rock was used annually in the Woods Hole establishment. Great piles of rock were left lying out of doors and under sheds; at one time, it was estimated that there were seven or eight hundred tons on hand. The only damage to which it is liable from exposure was that it collected moisture and became more difficult to grind. In such cases, it was piled in great heaps upon a brick floor, and roughly kiln-dried by a fire of soft coal kindled under it.[2]

The sulphuric acid used was manufactured on the spot from Sicily sulphur, which was brought in vessels from Boston and direct from the Sicily. About 1,200 tons of sulphur were used annually, and not far from 3,000 tons of sulphuric acid. The sulphuric acid used in manufacture was brought up to a standard density indicated by 66 on the Baumé hydrometer, a specific gravity of 1.7674.[2]

The buildings used in this branch of the business were nearly as extensive as all the others. The three leaden tanks had a capacity of 185,000 cubic feet, the smaller containing 48,000 the others 2,000 and 6,500 respectively.[2]

In the early days of the business, the sulphuric acid was brought from Waltham, Massachusetts, and New Haven, Connecticut, in carboys, but from 1866, it was manufactured in Woods Holl at a large saving of expense. The Leopoldshall kainit, which averaged about 123 per cent potash, came from the mines at Leopoldshall, near Staßfurt, Germany. Its use was comparatively recent, having been impracticable to obtain it in any considerable quantity. Close to 500 tons were used annually. It took the place of the coarse salt formerly used, a refuse product from the gunpowder works at New Haven.[2]

The Charleston, South Carolina plant consumed immense quantities of menhaden scrap brought from the water by the vessels which carried on their return trip a supply of South Carolina phosphates for the Wood's Hole factory.[3]

Production

[edit]The process of manufacture was sufficiently simple. The fish-scrap, on its reception, was stored, after being mixed with about 3 per cent. of its weight of kainite. This was a precaution necessary to prevent fermentation and putrefaction. Common salt was formerly used fer this purpose. The phosphate, as needed, was crushed in a stone-crushing machine, and ground between millstones to the consistency of fine flour. An arrangement of hoppers and elevators facilitated this part of the work.[2]

The scrap having been stored in one wing of the factory, the ground phosphate in another, the sulphuric acid having been forced into a reservoir near by, by pneumatic pressure, the process of mixing was easily carried on. For this work, two of Poole & Hunt's patent mixers were employed. These were larger basins of iron, each of which contained about a ton of the mixed material. In these the ingredients were placed in the proportion of 1,000 pounds of phosphate, 900 of scrap, and from 300 to 450 pounds of sulphuric acid. The basins then revolved rapidly, while a series of plows on one side, also revolving, thoroughly stirred the mass which passed under them. Fifteen minutes sufficed for a thorough mixture, and the guano was removed to a storage shed, where it remained for six weeks or more to allow the ingredients to thoroughly combine. It was then thrown into hoppers, passed through rapidly-revolving wire screens, and after it has been packed in 200-pound sacks, it was ready for the market. About 600 bags could be filled in a day.[2]

Before the invention of the Poole & Hunt mixing machine, the guano was mixed with hoes in large wooden or stone tubs. This process was laborious and very expensive, and various machines were devised, but they proved failures because the materials caked, clogging the wheels and knives in a very short time.[2]

The guano often contained hard lumps which could not be pulverized by the wire screen. Residue of this kind was subjected to the action of the Carr's disintegrator, which consisted of two wheels revolving in opposite directions at the rate of 600 revolutions to the minute.[2]

Criticism and controversy

[edit]The offensive odor of the factories rendered them disagreeable to persons residing in the neighborhood, and legal measures were taken in one or two instances to prevent the manufacturers from carrying on their business. In Connecticut vs. Enoch Coe, of Brooklyn, New York, on May 5, 1871, at the session of the United States circuit court in New Haven, Judge Lewis Bartholomew Woodruff granted an injunction to restrain the defendant from manufacturing manure from fish at his works in Norwalk Harbor, on the ground that the same created a nuisance. In 1872, the Shelter Island Camp-meeting Association made an effort to have the factories on Shelter Island closed, on the same grounds. People interested in building up Woods Holl as a watering place once agitated legal measures to compel a removal of the works, but the general sentiment of the town of Falmouth, Massachusetts in which the company paid heavy taxes, and specially of the many villagers of Woods Hole who earn their living in the works, prevented any results.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ The Pacific guano company; its history; its products and trade; its relation to agriculture. Exhausted guano islands of the Pacific ocean; Howland's island, Chiacha islands, etc., etc. The Swan islands. The marl beds and phosphate rock of South Carolina. Chisolm's island phosphate. The menhaden. Cambridge: Riverside press. 1876. Retrieved 9 November 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Goode, G. Brown (George Brown); Atwater, W. O. (Wilbur Olin) (1880). "A Description of the factory of the Pacific Guano Company, at Wood's Holl, Mass., by Messrs. Crowell and Shiverick, of the Pacific Guano Company, and short-hand notes taken by Mr. H. A. Gill.". American fisheries: a history of the menhaden. New York: Orange Judd. pp. 487–90. Retrieved 9 November 2024 – via Internet Archive.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c United States Bureau of Fisheries (1879). Report on the Condition of the Sea Fisheries of the South Coast of New England. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 166, 169, 228, 529. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Cullen, Vicky (2005). Down to the Sea for Science: 75 Years of Ocean Research, Education, and Exploration at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Woods Hole Oceanographic Insitution. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-880224-09-0. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

External links

[edit]- The Pacific Guano Company via Woods Hole Museum