Bortezomib

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Velcade, others |

| Other names | PS-341 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 83% |

| Metabolism | Liver, CYP extensively involved |

| Elimination half-life | 9 to 15 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.601 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

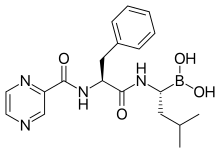

| Formula | C19H25BN4O4 |

| Molar mass | 384.24 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Bortezomib, sold under the brand name Velcade among others, is an anti-cancer medication used to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma.[4] This includes multiple myeloma in those who have and have not previously received treatment.[3] It is generally used together with other medications.[3] It is given by injection.[4]

Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, tiredness, low platelets, fever, numbness, low white blood cells, shortness of breath, rash and abdominal pain.[4] Other severe side effects include low blood pressure, tumour lysis syndrome, heart failure, and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome.[4][3] It is in the class of medications known as proteasome inhibitor.[4] It works by inhibiting proteasomes, cellular complexes that break down proteins.[3]

Bortezomib was approved for medical use in the United States in 2003 and in the European Union in 2004.[4][3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[6]

Medical use

[edit]Two open-label trials established the efficacy of bortezomib (with or without dexamethasone) on days 1,4,8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle for a maximum of eight cycles in heavily pretreated people with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.[7] The phase III demonstrated the superiority of bortezomib over a high-dose dexamethasone regimen (e.g. median TTP 6.2 vs 3.5 months, and 1-year survival 80% vs 66%).[7] New studies show that bortezomib may potentially help recover from vincristine treatment in treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia, when replacing vincristine in the process.[8]

Bortezomib was also evaluated together with other drugs for the treatment of multiple myelomas in adults. It was seen that bortezomib plus lenalidomide plus dexamethasone as well as bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone may result in a large increase in the progression-free survival.[9]

Adverse effects

[edit]Gastro-intestinal effects and asthenia are the most common adverse events.[10] Bortezomib is associated with peripheral neuropathy in 30% of people resulting in pain. This can be worse in people with pre-existing neuropathy. In addition, myelosuppression causing neutropenia and thrombocytopenia can also occur and be dose-limiting. However, these side effects are usually mild relative to bone marrow transplantation and other treatment options for people with advanced disease. Bortezomib is associated with a high rate of shingles,[11] although prophylactic acyclovir can reduce the risk of this.[12]

Ocular side effects such as chalazion or hordeolum (stye) may be more common in women and have led to discontinuation of treatment.[13] Acute interstitial nephritis has also been reported.[14]

Drug interactions

[edit]Polyphenols derived from green tea extract including epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which were expected to have a synergistic effect, instead were found to reduce the effectiveness of bortezomib in cell culture experiments.[15]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Structure

[edit]The drug is an N-protected dipeptide and can be written as Pyz-Phe-boroLeu, which stands for pyrazinoic acid, phenylalanine and Leucine with a boronic acid instead of a carboxylic acid.

Mechanism

[edit]The boron atom in bortezomib is proposed to bind the catalytic site of the 26S proteasome[16] with high affinity and specificity. In normal cells, the proteasome regulates protein expression and function by degradation of ubiquitylated proteins, and also rids the cell of abnormal or misfolded proteins. Clinical and preclinical data support a role for the proteasome in maintaining the immortal phenotype of myeloma cells, and cell-culture and xenograft data support a similar function in solid tumor cancers. While multiple mechanisms are likely to be involved, proteasome inhibition may prevent degradation of pro-apoptotic factors, thereby triggering programmed cell death in neoplastic cells. Bortezomib causes a rapid and dramatic change in the levels of intracellular peptides that are produced by the proteasome.[17] Some intracellular peptides have been shown to be biologically active, and so the effect of bortezomib on the levels of intracellular peptides may contribute to the biological and/or side effects of the drug.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

[edit]After subcutaneous administration, peak plasma levels are ~25-50 nM and this peak is sustained for 1-2 hrs. After intravenous injection, peak plasma levels are ~500 nM but only for ~5 minutes, after which the levels rapidly drop as the drug distributes to tissues (volume of distribution is ~500 L).[18][19] Both routes provide equal drug exposures and generally comparable therapeutic efficacy. Elimination half life is 9–15 hours and the drug is primarily cleared by hepatic metabolism.[20]

The pharmacodynamics of bortezomib are determined by quantifying proteasome inhibition in peripheral blood mononuclear cells taken from people receiving the drug.

History

[edit]Bortezomib was originally made in 1995 at Myogenics. The drug (PS-341) was tested in a small Phase I clinical trial on people with multiple myeloma. It was brought to further clinical trials by Millennium Pharmaceuticals in October 1999.[21]

In May 2003, bortezomib (marketed as Velcade by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc.) was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in multiple myeloma, based on the results from the SUMMIT Phase II trial.[22][23] In 2008, bortezomib was approved in the United States for initial treatment of people with multiple myeloma.[24] Bortezomib was previously approved in 2005, for the treatment of people with multiple myeloma who had received at least one prior therapy and in 2003, for the treatment of more refractory multiple myeloma.[24]

The 2008 approval was based on an international, multicenter, open label, active-control trial in previously untreated people with symptomatic multiple myeloma.[24] People were randomized to receive either nine cycles of oral melphalan (M) plus prednisone (P) or MP plus bortezomib.[24] People received M (9 mg/m2 ) plus prednisone (60 mg/m2 ) daily for four days every 6 weeks or the same MP schedule with bortezomib, 1.3 mg/m2 iv on days 1, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29, and 32 of every 6 week cycle for 4 cycles then once weekly for 4 weeks for 5 cycles.[24] Time- to- progression (TTP) was the primary efficacy endpoint.[24] Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and response rate (RR) were secondary endpoints.[24] Eligible people were age > 65 years.[24] A total of 682 people were randomized: 338 to receive MP and 344 to the combination of bortezomib plus MP.[24] Demographics and baseline disease characteristics were similar between the two groups.[24]

The trial was stopped following a pre-specified interim analysis showing a statistically significant improvement in TTP with the addition of bortezomib to MP (median 20.7 months) compared with MP (median 15 months) [HR: 0.54 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.70), p= 0.000002].[24] OS, PFS, and RR also were significantly superior for the bortezomib-MP combination.[24]

In August 2014, bortezomib was approved in the United States for the retreatment of adults with multiple myeloma[25][26] who had previously responded to Velcade therapy and relapsed at least six months following completion of prior treatment.[26]

In October 2014, bortezomib was approved in the United States for the treatment of treatment-naïve people with mantle cell lymphoma.[26]

A ready-to-use formulation of bortezomib was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2024.[2][27]

Society and culture

[edit]Economics

[edit]In the UK, NICE initially recommended against Velcade in October 2006, due to its cost of about £18,000 per person, and because studies reviewed by NICE reported that it could only extend the life expectancy by an average of six months over standard treatment.[28] However, the company later proposed a performance-linked cost reduction for multiple myeloma,[29] and this was accepted.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ "Bortezomib Baxter (Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 2 May 2024. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Boruzu- bortezomib injection". DailyMed. 27 September 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Velcade EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bortezomib Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "2022 First Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 March 2023. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ a b Curran MP, McKeage K (2009). "Bortezomib: a review of its use in people with multiple myeloma". Drugs. 69 (7): 859–88. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969070-00006. PMID 19441872. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ Joshi J, Tanner L, Gilchrist L, Bostrom B (August 2019). "Switching to Bortezomib may Improve Recovery From Severe Vincristine Neuropathy in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 41 (6): 457–462. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000001529. PMID 31233464. S2CID 195357104.

- ^ Piechotta V, Jakob T, Langer P, Monsef I, Scheid C, Estcourt LJ, et al. (Cochrane Haematology Group) (November 2019). "Multiple drug combinations of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and thalidomide for first-line treatment in adults with transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013487. PMC 6876545. PMID 31765002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ "Highlights Of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Oakervee HE, Popat R, Curry N, Smith P, Morris C, Drake M, et al. (June 2005). "PAD combination therapy (PS-341/bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone) for previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma". British Journal of Haematology. 129 (6): 755–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05519.x. PMID 15953001. S2CID 34591121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Pour L, Adam Z, Buresova L, Krejci M, Krivanova A, Sandecka V, et al. (April 2009). "Varicella-zoster virus prophylaxis with low-dose acyclovir in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bortezomib". Clinical Lymphoma & Myeloma. 9 (2): 151–3. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.036. PMID 19406726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Dennis M, Maoz A, Hughes D, Sanchorawala V, Sloan JM, Sarosiek S (March 2019). "Bortezomib ocular toxicities: Outcomes with ketotifen". American Journal of Hematology. 94 (3): E80–E82. doi:10.1002/ajh.25382. PMID 30575098.

- ^ Cheungpasitporn W, Leung N, Rajkumar SV, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Angioi A, et al. (July 2015). "Bortezomib-induced acute interstitial nephritis". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 30 (7): 1225–9. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv222. PMID 26109684.

- ^ Golden EB, Lam PY, Kardosh A, Gaffney KJ, Cadenas E, Louie SG, et al. (June 2009). "Green tea polyphenols block the anticancer effects of bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors". Blood. 113 (23): 5927–37. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-171389. PMID 19190249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Bonvini P, Zorzi E, Basso G, Rosolen A (April 2007). "Bortezomib-mediated 26S proteasome inhibition causes cell-cycle arrest and induces apoptosis in CD-30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma". Leukemia. 21 (4): 838–42. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404528. PMID 17268529.

- ^ Gelman JS, Sironi J, Berezniuk I, Dasgupta S, Castro LM, Gozzo FC, et al. (2013). "Alterations of the intracellular peptidome in response to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e53263. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853263G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053263. PMC 3538785. PMID 23308178.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Reece DE, Sullivan D, Lonial S, Mohrbacher AF, Chatta G, Shustik C, et al. (January 2011). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of two doses of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 67 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1007/s00280-010-1283-3. PMC 3951913. PMID 20306195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Voorhees PM, Dees EC, O'Neil B, Orlowski RZ (December 2003). "The proteasome as a target for cancer therapy". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (17): 6316–25. PMID 14695130.

- ^ Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, Karamanesht I, Leleu X, Grishunina M, et al. (May 2011). "Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study". The Lancet. Oncology. 12 (5): 431–40. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70081-x. PMID 21507715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Larkin M (November 1999). "(In)famous trials brought to life". The Lancet. 354 (9193): 1915. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)76886-0. ISSN 0140-6736. S2CID 53301933.

- ^ Adams J, Kauffman M (2004). "Development of the proteasome inhibitor Velcade (Bortezomib)". Cancer Investigation. 22 (2): 304–11. doi:10.1081/CNV-120030218. PMID 15199612. S2CID 23644211.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Velcade (Bortezomib) NDA #021602". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 May 2003. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Velcade (bortezomib) is Approved for Initial Treatment of Patients with Multiple Myeloma" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Company". .millennium.com. 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Raedler L (March 2015). "Velcade (Bortezomib) Receives 2 New FDA Indications: For Retreatment of Patients with Multiple Myeloma and for First-Line Treatment of Patients with Mantle-Cell Lymphoma". American Health & Drug Benefits. 8 (Spec Feature): 135–40. PMC 4665054. PMID 26629279.

- ^ "Amneal and Shilpa Announce U.S. FDA Approval of Boruzu, the First Ready-to-Use Version of Bortezomib for subcutaneous administration". Business Wire (Press release). 5 September 2024. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "NHS watchdog rejects cancer drug". BBC News Online. 20 October 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ "Summary of Velcade Response Scheme" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ "More Velcade-Style Risk-Sharing In The UK?". Euro Pharma Today. 21 January 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

External links

[edit]- "Bortezomib". NCI Drug Dictionary. National Cancer Institute.

- "Bortezomib". National Cancer Institute. 5 October 2006.