Oxnard Plain

Oxnard Plain | |

|---|---|

Region | |

| |

|

The Oxnard Plain is a large coastal plain in southwest Ventura County, California, United States surrounded by the mountains of the Transverse Ranges. The cities of Oxnard, Camarillo, Port Hueneme and much of Ventura as well as the unincorporated communities of Hollywood Beach, El Rio, Saticoy, Silver Strand Beach, and Somis lie within the over 200-square-mile alluvial plain (520 km2). The population within the plain comprises a majority of the western half of the Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura Metro Area and includes the largest city along the Central Coast of California. The 16.5-mile-long coastline (26.6 km) is among the longest stretches of continuous, linear beaches in the state.

The high quality soils, adequate water supply, favorable climate, long growing season, and level topography are characteristic of the Oxnard Plain where the top cash crops are strawberries, raspberries, nursery stock and celery.[1][2][3][4] Ventura County is one of the principal agricultural counties in the state and it is a significant component of the economy with a total annual crop value in the county of over $1.8 billion in 2014. There is strong public sentiment for retaining agricultural production, as reflected in the SOAR (Save Open Space and Agricultural Resources) initiatives that have been approved by voters.[5]

This plain has been formed chiefly by the deposition of sediments from the Santa Clara River and Calleguas Creek.[6] This plain contained a series of marshes, salt flats, sloughs, and lagoons prior to the expansion of agriculture. The Santa Clara River is one of the largest river systems along the coast of Southern California and only one of two remaining river systems in the region that remain in their natural states.[7] The Oxnard Plain faces the Santa Barbara Channel portion of the Southern California Bight, extending from the abrupt transition of the steep rocky shore at Point Mugu in the Santa Monica Mountains on the south to the Ventura River on the north.[8] Prominent on the southeastern horizon are Conejo Mountain and Boney Peak.

The Oxnard Plain contains a considerable petroleum reserve with several active oil fields – the Oxnard Oil Field, east of Oxnard, the West Montalvo Oil Field, along the coast south of the outlet of the Santa Clara River, and the Santa Clara Avenue Oil Field north of U.S. Highway 101 near El Rio. There are also several smaller abandoned oil fields. Oil facilities are interspersed with agricultural land uses both east and west of Oxnard.[9]

History

[edit]Prehistory and indigenous peoples

[edit]Human settlement at over 5000 B.C.E. has been documented in nearby coastal sites. These prehistoric sites may contain middens, milling stone sites, large villages, cemeteries, and tool making sites. The diversity of natural resources along with the temperate climate with a long growing season produced a lengthy archaeological record of human activity along the coast. Calleguas Creek and the Santa Clara River were populated with many Native American villages as evidenced by archaeological sites such as the Calleguas Creek Site that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.[10] Several sites have also been documented at Mugu Lagoon. The numerous archaeological sites in the adjacent Santa Monica Mountains also demonstrate the long history of human habitation.[11] Many of the sites are located adjacent to permanent water sources as the presence or absence of water is a crucial predictor of site location in Southern California. Many of the archaeological sites on the plain have been disturbed by erosion, farming, gophers, bulldozers, and other cultural and natural sources of disturbance.[12]

Spanish period (1782 to 1822)

[edit]Spanish explorers made sailing expeditions along the coast of southern California between the mid-1500s and mid-1700s. In the 18th century, Spain began the colonization and inland exploration of Alta California. They established a tripartite system consisting of missions, presidios, and pueblos. Mission San Buenaventura was founded in 1782 next to the Ventura River, 10 miles (16 km) upcoast from the Santa Clara River. The Oxnard plain was used for grazing herds of livestock which required thousands of acres. The traditional way of life of the Chumash people became increasingly unstable and unsustainable on the Oxnard Plain with the introduction of these animals. They also experienced further disruptive contacts through the increasing number of Europeans and Americans that visited the California coast looking for pelts from fur-bearing animals such as sea otters, and trade in hides and tallow beginning in the 1790s. The destruction wrought by the livestock and shortages of wild plants that they used for food may have made the missions appear to be the only viable alternative to a disintegrating way of life. At its peak in 1816, the mission had over 41,000 animals including 23,400 cattle, 12,144 sheep. The 4,493 horses constituted one of the largest stables of horses of the California mission sites. The Chumash culture, including political and social relationships between communities, trade, and inter-village marriage patterns, could not be sustained as more and more Indians abandoned their traditional way of life and entered the mission. The severe decrease in the Chumash population was in response to a complex set of social, economic, and demographic factors.[13]

Mexican period (1822-1848)

[edit]Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821. With the secularization of the missions by the Mexican government in June 1836, their lands were granted as rewards for loyal service or in response to petitions by individuals. Most of the arable land was divided up into large ranchos by 1846.[14] This opened up the Oxnard Plain to further settlement by Europeans.[13] Control of the area was transferred to the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and California became the 31st state in the Union in 1850. Many Mexican residents and residents who had immigrated from European countries became U.S. citizens.

Initial European migration

[edit]Many of the Spanish and Mexican rancho families benefited when the cattle market peaked between 1848 and 1855 due to the California Gold Rush.[15] Cattle ranching declined drastically when a drought hit the area in 1863.[16]

James Saviers bought property in Rancho Colonia in 1862. He was a blacksmith and farmer who grew and sold eucalyptus trees used to protect crops from the seasonal Santa Ana winds that originated inland and brought strong, hot, extremely dry winds to the treeless plain.[17] Settlers Gottfried Maulhardt and Christian Borchard along with Christian's son, John Edward, and nephew, Caspar began farming with 30 acres (12 ha) of wheat and barley in 1867.[18] New markets for the grain opened up when a shipping wharf was first constructed in 1871 at Hueneme.[19] Irish immigrant Dominick McGrath arrived in 1874 with his wife and children to begin farming on the plain.[20] Johnnas Diedrich, with his bride, Matilda, began a new life of farming in 1882 having come from Hanover, Germany.[21] New Jerusalem was founded in 1875 along the south bank of the Santa Clara River. The community, eventually renamed El Rio, was along the route between Ventura and Hueneme. Lima beans became the dominant crop as they could be grown with very little maintenance.[22] Farmers were actively growing trial fields of sugar beets in 1897.[23]

City development and growth

[edit]In 1887, as the railroad was constructed from Los Angeles to the town of San Buenaventura, the Montalvo station was established on the plain on the north side of the river. In 1898 the Montalvo Cutoff brought the railroad across the Santa Clara River at El Rio and then due south to where the town of Oxnard was being established. The Oxnard Brothers built the American Beet Sugar Company factory on land in the middle portion of the plain that they bought from James Saviers.[17][24] He became a judge and an honorary justice of the peace: Saviers Road was named after him in the new city of Oxnard that arose around the factory.[17] The railroad continued with tracks heading east out of Oxnard and eventually being extended to Santa Susana in Simi Valley. Traffic on the coast railroad line was rerouted through Oxnard in 1904 with the completion of the Santa Susana Tunnel as this became the most direct route between Los Angeles and San Francisco.[25]

Agriculture as an industry, as differentiated from family farming, began with the access to the railroad network. In 1903, this transition in agriculture labor practices found Japanese and Mexican sugar beet workers and labor contractors united in protest as the growers, backed by financiers, slashed the wage rate by 50 percent and sought to eliminate independent labor agents. The workers formed the Japanese Mexican Labor Association to press their concerns. While one ethnic group can often be pitted against another to undermine labor solidarity, the Oxnard Strike of 1903 unified them, as their efforts brought the industry to a standstill until their demands were met.[26]

In 1911, J. Smeaton Chase noted the "prosperous fields of beans and beets" as he descended from the Santa Monica Mountains onto the Oxnard Plain during his 2,000-mile (3,200 km) horseback journey from Mexico to Oregon. In his book about the journey, he describes the "sleepy little coast village of Hueneme" as a "ghost of a once flourishing town" due to the establishment of a beet sugar factory. The once busy port had drastically declined as passenger and freight traffic shifted to the railroad.[27]

Postwar and modern development

[edit]

Although agriculture has long been important to the economy on the Oxnard Plain, the booming growth in the 1960s of the cities located on the plain expanding by building housing, highways, and associated infrastructure over the rich agricultural land.[28][29] Several methods were tried to encourage the building in compact, connected ways and reduce urban sprawl into the agricultural lands. "Guidelines for orderly development" were adopted in 1969 by the County of Ventura to encourage urban development to be located within incorporated cities whenever or wherever practical. Eventually greenbelt agreements were established between cities to further define the areas of growth.[30] A growth control ordinance was adopted by the city of Ventura in 1995.[31] "Save Open-space and Agricultural Resources" (SOAR) was the name given to these plans that would limit housing and commercial development on farmland surrounding the cities.[32] Jean Harris and other activists pressured the Oxnard city council to present a measure to the voters. Oxnard, Camarillo and Ventura County SOAR initiatives were overwhelmingly approved by voters in 1998. Under SOAR, the farmland and open space outside each city's urban growth boundary could not be rezoned without voter approval through 2020.[33][34] The City of Ventura SOAR regulations expire at the end of 2030.[33][35]

Ballot initiatives in 2016 proposed to extend the growth control ordinance for another 30 years.[36][37] As measures to renew SOAR were placed on the ballot county-wide in 2016, an alternative proposal was put forth by the agricultural interests.[38]

As of 2014[update], farmland values in California were at historic highs and the agricultural industry was optimistic and even confident about the future.[39][40] Pesticide use is an issue in the interface between agriculture and residential areas along with public uses such as schools.[41][42]

While the vast fields of fertile soil were appreciated for the agricultural bounty that could be produced, the sand dunes and wetlands along the coast line were considered useless except as places to dispose of solid and liquid waste. This at least dates back to 1898 when the beet sugar factory sent the wastewater discharge through a pipe to Ormond Beach. Various other areas near the coast were used for dumping trash and oil-waste, much of the time with local government encouragement and supervision.[43] The Halaco Engineering Co., a metal recycling facility at the Ormond Beach wetlands, deposited process wastes and wastewater from the smelter from 1965 until 2004 on what was allegedly a former open dump operated by the City of Oxnard until 1962. The waste pile contains an estimated 112,900 cubic yards (86,300 m3) and the facility has been designated a Superfund site.[44] Other large, polluting industries were cited at Ormond Beach wetlands before environmental concerns highlighted the importance of restoring the area to serve as a dynamic habitat for a wide array of native plants and animals.[45]

Over the years, many communities have attempted to control the Santa Clara River by establishing dumps along the banks to create levees that would keep the river from flooding adjacent lands during occasional years with heavy winter rains. Three dump sites about 2 miles (3.2 km) upstream from the mouth of the river came under the control of the Ventura Regional Sanitation District by 1988. They continued to use the sites until they were closed in 1996.[46]

Municipal wastewater treatment facilities, industrial dischargers, and power generating stations are point source dischargers along the coast of the Oxnard plain. Water quality at the numerous beaches has been very good with a few exceptions.[47] Two power generating stations were built in the 1960s to take advantage of the ocean for cooling.[48] Reliant Energy purchased the Mandalay Generating Station from Southern California Edison in 1998.[49] The Oxnard City council tried to prevent a third plant from being built in 2012. After years of legal tussles, the 45 megawatts (60,000 hp) McGrath Peaker Plant was built by Edison next to the power plant at Mandalay.[50]

Geography

[edit]This plain is bounded by the Santa Monica Mountains, the Santa Susana Mountains, the Topatopa Mountains to the north, the Santa Clara River Valley to the northeast and the Santa Barbara Channel to the south and west.[6] The topography of the plain is relatively level. It has been formed chiefly by the deposition of sediments from Santa Clara River Valley and the watershed of Calleguas Creek before they flow into the Pacific Ocean.[6] The alluvial deposits from these rivers are generally a few hundred feet (30 metres) thick and lie over Pleistocene and Pliocene sedimentary rocks.[51] The Santa Clara River is one of the largest river systems along the coast of Southern California and only one of two remaining river systems in the region that remain in their natural states and not channelized by concrete.[52] Prior to the agricultural expansion, installation of drainage systems, and other disturbances, this broad, flat, coastal area contained a series of marshes, salt flats, sloughs, and lagoons.[53]: xix Historically, Calleguas Creek flood flows spread across the floodplain and the deposited sediment created the rich agricultural lands of the Oxnard Plain. With year-round agriculture in the floodplain, concrete channels and dirt levees have been built to contain the flow. This has delivered increased sediment to Mugu Lagoon and flooding during extreme rain events.[54]: 4–13 The 16.5-mile-long coastline (26.6 km) is among the longest stretches of continuous, linear beaches in the state. With the Port of Hueneme, Channel Islands Harbor, and Ventura Harbor along with a number of breakwaters, jetties and groins, this is one of the most engineered coastlines in the state with complicated coastal geography.[7]: 56 [55]

Groundwater

[edit]

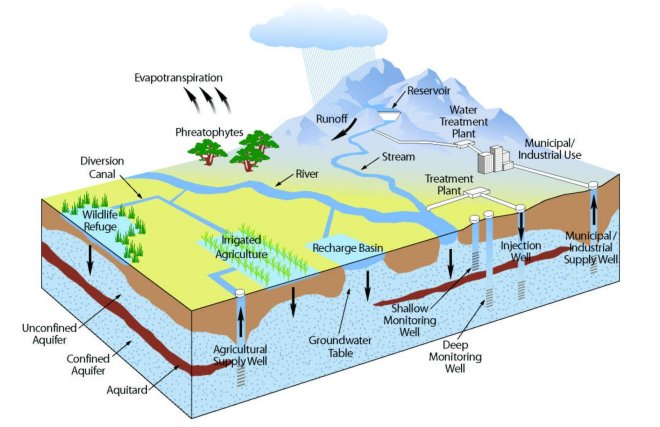

Saltwater intrusion from the ocean has occurred in the southern Oxnard Plain due to the overdraft of groundwater. The Santa Clara Irrigating Company was formed in 1870 and drew water from the Santa Clara River, using a ditch system to irrigate the grain crops.[19] Early settlers began pumping soon afterwards to support farming activities with what at first was a more reliable source. In the modern era, much of the groundwater has been rendered useless for agricultural or potable uses by salt-water intrusion. Unlike coastal Los Angeles and Orange County, Ventura County has no barrier in place to prevent the ocean water from intruding into the inland aquifers.[56]

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act signed into California law in 2014 created a framework for sustainable, local groundwater management for the first time in California history. In response, the Ventura County Board of Supervisors passed an emergency ordinance that halted well-drilling in the Oxnard Plain. Groundwater levels experienced a decrease during the 2012–2013 drought.[57]

Calleguas Municipal Water District

[edit]Calleguas Municipal Water District, a water wholesaler, serves about 75 percent of Ventura County's population. Calleguas ships state water from the Delta to Oxnard, Port Hueneme, and Camarillo on the Oxnard Plain and Moorpark, Thousand Oaks, Simi Valley and unincorporated areas in the east county.[58] These areas also use groundwater and surface water supplies but these sources have increased in salinity. The source of the salts is a combination of agricultural, industrial, and residential activities in conjunction with salts in the imported water.[56] The United Water Conservation District funded a detailed feasibility study in 2014 and found that the impaired groundwater in the south Oxnard Plain is suitable for treatment by reverse osmosis at an acceptable recovery range of 72 to 80 percent.[56] Many local agencies, particularly those in the Calleguas Creek Watershed, have built or are putting in desalters to treat salty groundwater. The treated water can be used for drinking supplies which will make the region less dependent on imported state water. The remaining salt concentrate will be sent out to sea through the Calleguas Regional Salinity Management Project. This $220 million pipeline project started in 2003 and stretches from the marine outfall into Simi Valley.[58][59] That pipeline services desalters in Simi Valley, Moorpark and the Camrosa Water District in the Santa Rosa Valley.

Camarillo and Santa Rosa Valley

[edit]The city of Camarillo water system serves about two-thirds of its residents.[60] It imports about 60 percent of its water from the state water project through the Calleguas Municipal Water District and 40 percent is pumped from three wells. The North Pleasant Valley Desalter Project is a $66.3 million project to treat brackish well water.[61][62] The project began construction in September, 2019.[63] The city held a ribbon cutting ceremony in November 2021 as the plant began to operate.[64] After extensive testing and adjustments, the plant started producing water for the city in January 2023.[65]

The Camrosa Water District serves nearly 30,000 people in Camarillo and the Santa Rosa Valley along with agricultural customers.[66] The district, which covers 31 square miles (80 km2) is headquartered in Camarillo. Camrosa completed the Round Mountain Water Treatment Plant, a desalting facility, in 2015. It cleans up brackish groundwater and produces 1,000 acre-feet (1,200,000 m3) of drinking water a year. The facility was the first paying customer for the Calleguas Regional Salinity Management Project.[66][67]

Oxnard

[edit]In 2008, the city started up a desalination plant near the Oxnard Transit Center that treats the brackish groundwater from nearby wells.[68] The water supply in the Oxnard Plain has been expanded by a $71 million Advanced Water Purification Facility (AWPF) built by the city of Oxnard. The plant scrubs treated sewage water to super-clean levels that can be used on crops, by industrial customers, and for water landscaping. The water can also be injected into the ground from where it can be pumped out months later for use in the drinking supply.[69] When the final permits were in place, the AWPF began providing water to a lake at the River Ridge Golf Course in 2015. Water from the lake is used to irrigate the golf course. Gradually, pipelines begin serving city parks, street medians, and all the landscaping in new developments including two along the Santa Clara River: RiverPark, a community of 1,800 homes and Wagon Wheel with 1,500 apartments and condos.[70] The water is also provided to industrial customers and farmers near the plant. Initially pipelines needed to reach additional farmers served by the Pleasant Valley County Water District with 15,200-acre-foot a year (18,700,000 m3) were not finished until 2016 but the district was able to temporarily use the brine line to get the water to the farmers during the drought.[71][72][73][74]

United Water Conservation District

[edit]Formed in 1950, the United Water Conservation District battles groundwater overdraft through a combination of aquifer recharge and providing alternative surface water supplies. The District encompasses about 214,000 acres (87,000 ha)[75] and owns Lake Piru and key facilities along the Santa Clara River that are used to manage groundwater supplies.[76] The United Water Conservation District provides wholesale water delivery through three pipelines to various portions of the Oxnard Plain. One is the Oxnard/Hueneme system which serves the City of Oxnard, the Port Hueneme Water Agency (City of Port Hueneme, Channel Islands Beach CSD) and the Naval Base Ventura County (Point Mugu and the Construction Battalion Center).[77] A second pipeline serves agricultural uses in the Oxnard Plain.[78] The third system supplies water to the Pleasant Valley area located between Oxnard and Camarillo.[79] United rates for non-agricultural uses are at least three times more than agricultural users are charged as required by the state water code.[80]

The Vern Freeman Diversion Dam, built by United Water in 1991 on the Santa Clara river, channels water to shallow basins designed to replenish the aquifer.[81] For decades before the structure was built, earthen dams were constructed in the river to divert water to farmers and replenished the aquifer. The berms would have to be rebuilt whenever winter rains created a flow that breached the berms.[82] Southern California Steelhead were declared endangered in 1997 and the fish ladder on the structure was deemed insufficient. The National Marine Fisheries Service determined that fixing this was a high priority since it is the first structure the steelhead encounter when attempting to migrate from the ocean.[83]

United released water from Lake Piru to specifically recharge the Fox Canyon in the Oxnard Plain for the first time in 2019.[84][85]

Ormond Beach

[edit]

Ormond Beach is a 1,500 acres (610 ha) broad, flat, coastal area on the south side of the Oxnard Plain that historically contained marshes, salt flats, sloughs, and lagoons. The expansion of agriculture and industry have drained, filled and degraded much of the wetlands over the past century but the area does have a dune-transition zone–marsh system along much of two-mile-long beach (3.2 km) that extends from Port Hueneme to the northwestern boundary of Point Mugu Naval Air Station.[86][29][87]

Hazards

[edit]The coastline is subject to inundation by a tsunami up to 23 feet in height.[88]

See also

[edit]- Ballona Wetlands

- California coastal prairie

- Coastal Strand

- Environment of California: Human impact on the environment

- Los Angeles Basin

References

[edit]- ^ Varian, Ethan (May 22, 2019). "How celery became the unlikely star of the produce aisle". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Harris, Mike (June 14, 2016). "Oxnard's Mandalay Berry Farms closing; 565 employees losing jobs". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Mohan, Geoffrey (May 25, 2017). "To keep crops from rotting in the field, farmers say they need Trump to let in more temporary workers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

Consumer tastes for fresh strawberries and leaf lettuce — two of the state's most stubbornly labor-intensive crops — have driven the boom along a coastal corridor from the Salinas Valley in Monterey County through the Oxnard Plain in Ventura County, according to the Times analysis.

- ^ Esquivel, Paloma (May 28, 2012). "Epithet that divides Mexicans is banned by Oxnard school district". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ "Crop Report 2012" Archived 2014-11-12 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Agricultural Commissioner

- ^ a b c Thomas, H. E., and Others (1962) "Effects of Drought Along Pacific Coast in California: 1942–56" Archived 2016-05-04 at the Wayback Machine Geological Survey Professional Paper, Volume 372-G. United States Department of the Interior

- ^ a b Hapke, Cheryl J.; Reid, David; Richmond, Bruce M.; Ruggiero, Peter; and List, Jeff (2006) "National Assessment of Shoreline Change Part 3: Historical Shoreline Change and Associated Coastal Land Loss Along Sandy Shorelines of the California Coast" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Geological Survey

- ^ "SUBSEQUENT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT FOR FOCUSED GENERAL PLAN UPDATE and Related Amendments to the Non-Coastal Zoning Ordinance and Zone Change ZN05-0008" Archived 2017-08-13 at the Wayback Machine County of Ventura (June 22, 2005)

- ^ Wilson, Kathleen (April 25, 2019). "45-day moratorium on drilling of certain oil wells passes". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Carlson, Cheri (February 8, 2014). "Dozens of archaeological sites discovered in wake of Springs Fire". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019.

- ^ Gamble, Lynn H. (2008). The Chumash World at European Contact: Power, Trade, and Feasting Among Complex Hunter-Gatherers. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520254411.

- ^ a b Jackson, Robert H.; Gardzina, Anne (2012). "Agriculture, Drought, and Chumash Congregation in California Missions (1782–1834)"]". California Mission Studies Association. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ^ Historic Resources Report, 1600 W. Fifth Street, Oxnard, CA (Mira Loma Apartments) Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine San Buenaventura Research Associates, Santa Paula, California 18 February 2008

- ^ Board of Supervisors (June 28, 2011) "General Plan Resources Appendix" Archived 2014-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Section 1.8.3.1 Historical Resource Description Ventura County

- ^ California Coastal Commission (1987). California Coastal Resource Guide. University of California Press. p. 267. ISBN 0520061853.

- ^ a b c "Putting Down Roots: Ventura County’s Immigrant Farmers, 1800–1910" Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Museum of Ventura County Website Agricultural Museum: History of Ventura County. Accessed 17 February 2014

- ^ Maulhardt, Jeffrey Wayne (2001). Beans, Beets, & Babies. Camarillo, CA: MOBOOKS. ISBN 0-9657515-2-X.

- ^ a b "Historic Resources Report: 6135 N. Rose Avenue, Saticoy, CA" Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine San Buenaventura Research Associates, Santa Paula, California 18 July 2011

- ^ Murphy, Arnold L. Compiler (1979) "A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California" Archived 2016-05-21 at the Wayback Machine M & N Printing, Oxnard

- ^ Obituaries (May 29, 1996) "Edwin Diedrich; Oxnard Farmer" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Pompey, Tim (May 6, 2021). "The End of an Era | The Maulhardts and the history of agriculture in Ventura County". VC Reporter | Times Media Group. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Ventura County: Hueneme Archived 2014-12-14 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Herald 25 September 1897 Volume 26, Number 360, Page 7

- ^ "Oxnard, California", BEET SUGAR, The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer, no. XXIX No. 1, p. 59, July 5, 1902, retrieved January 23, 2019 – via Google Books

- ^ "CHATSWORTH PARK CUTOFF LINE OPENS TODAY" Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Herald 20 March 1904. Volume XXXI, Number 173, Page 2

- ^ Barajas, Frank P. (January 26, 2014). "Local 'farmers' buy trucks, too". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ Chase, J. Smeaton (1913). "California Coast Trails: a Horseback Ride from Mexico to Oregon" Chapter VI. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Reprinted in The Double Cone Register, the online journal of the Ventana Wilderness Alliance, Volume VIII, No. 1, Fall 2005

- ^ Keppel, Bruce (November 23, 1987). "Region's Farmers Being Weeded Out By Urbanization". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Kelley, Daryl (April 29, 2001) "Illness Forces Environmental Crusader to Sidelines." Los Angeles Times

- ^ Harris, Mike (June 25, 2014). "Ventura County corridor ranked in top third of least sprawling areas". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Schniepp, Mark (February 7, 1999). "An Economist Looks at SOAR". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ Murillo, Cathy (March 9, 1998) "Oxnard to Consider Growth Limit" Los Angeles Times

- ^ a b "SOAR: What you need to know". Ventura County Star. May 30, 2015. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Bustillo, Miguel (November 5, 1998). "In Victory, SOAR Seeks Sense of Permanence". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014.

- ^ Fulton, William (November 7, 1999). "The Battle Between Two Ways to Manage Growth". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Kathleen (February 21, 2014) "Ventura County voters being asked to extend open-space protections until 2050" Archived 2015-04-19 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Martinez, Arlene (May 30, 2015). "SOAR proponents moving forward on campaign to renew open-space laws". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Kathleen (October 1, 2016). "For rival land-use measures, battle hinges on a few words". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ Brumback, Elijah (November 14, 2014) "Virginia REIT targets Central Coast ag land" Archived 2014-11-19 at the Wayback Machine Pacific Coast Business Times

- ^ Hoops, Stephanie (October 21, 2014) "Virginia company buys up Ventura County farmland" Archived 2014-10-23 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Barnes, Kathryn (March 31, 2015). "Too close for comfort: Pesticide spraying near Oxnard high school sheds light on statewide issue". KCRW. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Leung, Wendy (October 7, 2015). "Housing officials consider SOAR, density of future Ventura County developments". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ McCartney, Patrick (November 10, 1991). "Flynn Calls for Mandalay Bay Investigation : Oxnard: At issue is whether all traces of a landfill and oil-waste dump were removed before the waterfront housing was built". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "National Priorities List: Site Narrative for Halaco Engineering Company" Archived 2014-06-02 at the Wayback Machine US Environmental Protection Agency (November 27, 2012)

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (November 21, 2014) "Ormond Beach loses key planner, but vision remains" Archived 2014-11-25 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Munoz, Lorenza (August 26, 1996). "Oxnard Opens New Trash Transfer, Recycling Center". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Sercu, Bram (July 27, 2012). "Eye on the Environment: Clean beach measuring to improve". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (November 6, 2014) "NRG, emboldened by winning bid, wants Oxnard's support for new plant" Archived 2014-11-07 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Witthaus, Jack (March 6, 2023). "Southern California Canal Hits Market for $1 Million in Offbeat Waterfront Sale". CoStar. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (June 30, 2014). "Power plant battle to rattle Oxnard council chambers". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Hall, Clarence A. Jr. (October 23, 2007). Introduction to the Geology of Southern California and Its Native Plants. University of California Press. p. 254. ISBN 9780520933262.

- ^ "Additional facts about the area". Agriculture and Natural Resources, Ventura County. University of California Cooperative Extension. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Beller, E.E.; Grossinger, R.M.; Salomon, M.N.; Dark, S.J.; Stein, E.D.; Orr, B.K.; Downs, P.W.; Longcore, T.R.; Coffman, G.C.; Whipple, A.A.; Askevold, R.A.; Stanford, B.; Beagle, J.R. (2011). Historical ecology of the lower Santa Clara River, Ventura River, and Oxnard Plain: An Analysis of Terrestrial, Riverine, and Coastal Habitats. Publication 641. San Francisco Estuarine Institute. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ "2010 Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan for Ventura County, California – FINAL REPORT". Ventura County Hazards Mitigation Plan. County of Ventura. December 2010. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Peggy Y. (November 10, 1993) "Disputed South Beach Seawall Completed : Ventura Harbor: A group that fought the 650-foot jetty said it would cause erosion and ruin a top surfing spot." Los Angeles Times

- ^ a b c Carollo Engineers (August 2014) "South Oxnard Plain Brackish Water Treatment Feasiibilty Study: Technical Memorandum" Archived 2015-01-01 at the Wayback Machine United Water Conservation District

- ^ Wenzke, Marissa (November 21, 2014). "Running on empty: Ventura County puts curbs on water well drilling". Pacific Coast Business Times. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Wenner, Gretchen (October 17, 2011). "Pipeline construction in south Oxnard expected to wrap up in spring". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Calleguas Municipal Water District Regional Salinity Management Pipeline" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2017.

- ^ Rivers, Kimberly (January 21, 2021). "Inframark To Operate New Ddesalter | Camarillo approves $11 million contract". VC Reporter. Times Media Group. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (January 29, 2018). "California water: Desalination projects move forward with new state funding". Bay Area News Group. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018 – via Mercury News.

- ^ Hernandez, Marjorie (March 11, 2011). "Cities approve studies for regional desalter". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Childs, Jeremy (September 12, 2019). "Camarillo officials celebrate groundbreaking for long-planned desalter plant". Ventura County Star. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Varela, Brian J. (November 30, 2021). "Camarillo's next wave of water unveiled with long-awaited desalter facility". Ventura County Star. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Varela, Brian J. (January 23, 2023). "Camarillo's desalter plant begins supplying drinking water". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Wenner, Gretchen (April 17, 2015). "New water in the drought: Camrosa's long-range plans hit sweet target". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015. (subscription may be required for this article)

- ^ "Environmental Initial Study of the California State University Channel Islands Wellwater Desalter Project" (PDF). Camrosa Water District. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (September 17, 2011). "Oxnard touts ultra-pure water, but users balk at cost". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Leung, Wendy (March 6, 2021). "Oxnard to apply for $27.6M loan for recycled water project, readies for more street paving". Ventura County Star. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (April 16, 2015). "Perfect timing? Oxnard's recycled water plant makes first delivery". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (February 4, 2015) "Oxnard's recycled water deal a go, with delays" Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star (subscription may be required for this article)

- ^ Barnes, Lynne (May 26, 2004). "Oxnard Kicks Off Work on Water-Treatment Facility". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (May 2, 2015). "New water for Oxnard Plain farmers this summer?". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (July 5, 2015). "Oxnard hopes plan to send recycled water to farmers gets OK Thursday". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on July 6, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen. "Planned water treatment facility in El Rio to improve drinking water supply for thousands". Ventura County Star. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (December 31, 2011) "Brackish plant on Oxnard Plain could clean salty water" Archived 2015-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Varela, Brian J. (October 28, 2023). "$300M drought-busting water treatment facility in works at Naval Base Ventura County". Ventura County Star. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ Water Shortage Contingency Plan (PDF) (Report). United Water Conservation District. June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Water and Wastewater Municipal Service Review Report" (PDF). Ventura Local Agency Formation Commission. January 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Martinez, Arlene (March 17, 2015). "United Water's rates are fair to Ventura, appeals court rules – VC-Star". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Carlson, Cheri Ann (June 7, 2019). "Big boost of water is headed to Ventura County's overstressed groundwater basins". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Barlow, Zeke (May 26, 2011) "Little known Freeman Diversion shaped Ventura County" Archived 2015-04-28 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Wenner, Gretchen (January 23, 2015) "$60 million cost for fish passage has district reeling" Archived 2015-01-27 at the Wayback Machine Ventura County Star

- ^ Carlson, Cheri (July 24, 2019). "Close to $3 million of water has reached Ventura County's overstressed groundwater basin". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Carlson, Cheri (October 1, 2019). "Conflict, questions surface around $3 million water deal in Ventura County". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Ormond Beach Wetlands Restoration Project". California State Coastal Conservancy. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Grossinger, Robin; Stein, Eric D.; Cayce, Kristen; Askevold, Ruth; Dark, Shawna; Whipple, Alison. "Historical Wetlands of the Southern California Coast: An Atlas of US Coast Survey T-sheets, 1851-1889" (PDF). California State Coastal Conservancy, San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), Southern California Coastal Water Research Project (SCCWRP), California State University Northridge (CSUN). Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Lloyd, Jonathan (August 20, 2015). "Ventura, Oxnard Might Be at Greater Tsunami Risk: Study". NBC Southern California. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Maulhardt, Jeffrey Wayne (1999). The First Farmers of the Oxnard Plain: A biographical history of the Borchard and Maulhardt families. Camarillo, CA: MOBOOKS. ISBN 0965751511.