Miguel de Unamuno

This article contains translated text and needs attention from someone with dual fluency. (October 2024) |

Miguel de Unamuno | |

|---|---|

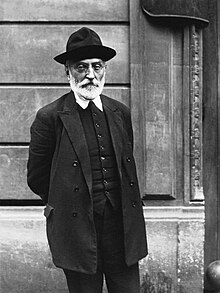

Unamuno in 1925 | |

| Born | Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo 29 September 1864 |

| Died | 31 December 1936 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Alma mater | Complutense University of Madrid |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Spanish philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Positivism Existentialism |

Main interests | Philosophy of religion, political philosophy |

Notable ideas | Agony of Christianity |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Spain |

|---|

|

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (Spanish: [miˈɣ̞el ð̞e̞ u.naˈmu.no i ˈxu.ɣ̞o]; 29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay was The Tragic Sense of Life (1912),[1] and his most famous novels were Abel Sánchez: The History of a Passion (1917),[2] a modern exploration of the Cain and Abel story, and Mist (1914), which Literary Encyclopedia calls "the most acclaimed Spanish Modernist novel".[3]

Biography

[edit]

Miguel de Unamuno was born in Bilbao, a port city of the Basque Country, Spain, the son of Félix de Unamuno and Salomé Jugo.[4] As a young man, he was interested in the Basque language, which he could speak, and competed for a teaching position in the Instituto de Bilbao against Sabino Arana. The contest was finally won by the Basque scholar Resurrección María de Azkue.[5]

Unamuno worked in all major genres: the essay, the novel, poetry, and theater, and, as a modernist, contributed greatly to dissolving the boundaries between genres. There is some debate as to whether Unamuno was in fact a member of the Generation of '98, an ex post facto literary group of Spanish intellectuals and philosophers that was the creation of José Martínez Ruiz (Azorín)—a group that includes, besides Azorín, Antonio Machado, Ramón Pérez de Ayala, Pío Baroja, Ramón del Valle-Inclán, Ramiro de Maeztu, and Ángel Ganivet, among others.[6]

Unamuno would have preferred to be a philosophy professor, but was unable to get an academic appointment; philosophy in Spain was somewhat politicized. Instead he became a Greek professor.[citation needed]

In 1901 Unamuno gave his well-known conference on the scientific and literary inviability of the Basque. According to Azurmendi, Unamuno went against the Basque language once his political views changed as a result of his reflection on Spain.[7]

In addition to his writing, Unamuno played an important role in the intellectual life of Spain. He served as rector of the University of Salamanca for two periods: from 1900 to 1924 and 1930 to 1936, during a time of great social and political upheaval. During the 1910s and 1920s, he became one of the most passionate advocates of Spanish social liberalism.[8] Unamuno linked his liberalism with his hometown of Bilbao, which, through its commerce and connection with the civilized world, Unamuno believed had developed an individualism and independent outlook in stark contrast to the narrow-mindedness of Carlist traditionalism.[9] When in 1912 José Canalejas was assassinated by an anarchist, he blamed it on the fact that Spain lacked a "true liberal democratic party" and in 1914 denounced the Spanish nobility for their alleged philistinism.[10] Along with many other Spanish writers and intellectuals, such as Benito Pérez Galdós, he was an outspoken supporter of the Allied cause during the First World War despite Spain's official neutrality.[11] Unamuno viewed the war as a crusade not just against the Imperial Family of the German Empire, but against the monarchy in Spain, and intensified his attacks upon King Alfonso XIII.[12]

Unamuno was removed from his two university chairs by the dictator General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1924, over the protests of other Spanish intellectuals. As a result of his vociferous criticisms of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, he lived in exile until 1930, first banished to Fuerteventura, one of the Canary Islands; his house there is now a museum,[13] as is his house in Salamanca. From Fuerteventura he escaped to France, as related in his book De Fuerteventura a Paris. After a year in Paris, Unamuno established himself in Hendaye, a border town in the French Basque Country, as close to Spain as he could get while remaining in France. Unamuno returned to Spain after the fall of General Primo de Rivera's dictatorship in 1930 and took up his rectorship again. It is said in Salamanca that the day he returned to the university, Unamuno began his lecture by saying, as Fray Luis de León had done after four years of imprisonment by the Spanish Inquisition, "As we were saying yesterday..." (Decíamos ayer...).

Also after the fall of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, Spain embarked on its Second Republic. He was a candidate on the Republican/Socialist ticket and was elected, after which he led a large demonstration in the Plaza Mayor in which he raised the Republic's flag and declared its victory.[14] He always was a moderate and refused all political and anticlerical. In a speech delivered on 28 November 1932, at the Madrid Ateneo, Unamuno protested against Manuel Azaña's anti-clerical policies: "Even the Inquisition was limited by certain legal guarantees. But now we have something worse: a police force which is grounded only on a general sense of panic and on the invention of non-existent dangers to cover up this over-stepping of the law."[15]

Unamuno's dislike for Manuel Azaña's ruling went so far as to tell a reporter who published his statement in El Adelanto in June 1936 that President Manuel Azaña "should commit suicide as a patriotic act".[16] The Republican government had a serious problem with this statement, and on 22 August 1936, they decreed that Unamuno should once again be removed from his position as rector of the university. Moreover, the government removed his name from streets and replaced it with the name of Simón Bolívar.

Having begun his literary career as an internationalist, Unamuno gradually became convinced of the universal values of Spanish culture, feeling that Spain's essential qualities would be destroyed if influenced too much by outside forces. Thus he initially welcomed Franco's revolt as necessary to rescue Spain from the Red Terror by forces loyal to the Second Spanish Republic.[17] When a journalist questioned how he could side with the military and "abandon a Republic that [he] helped create," Unamuno responded, it "is not a fight against the liberal Republic, but a fight for civilization. What Madrid represents now is not socialism or democracy, or even communism."[18]

However, the tactics employed by the Nationalist faction in the struggle against their republican opponents caused Unamuno to also turn against Franco. Unamuno said that the military revolt would lead to the victory of "a brand of Catholicism that is not Christian and of a paranoid militarism bred in the colonial campaigns," referring in the latter case to the 1921 war with Abd el-Krim in Spanish Morocco.[19][20]

In 1936 Unamuno had a public argument with Nationalist general Millán Astray at the university in which he denounced both Astray—with whom he had had verbal battles in the 1920s—and elements of the Nationalist faction. () Shortly afterwards, Unamuno was removed for a second time as the rector of the University of Salamanca. A few days later he confided to Nikos Kazantzakis:

No, I have not become a right-winger. Pay no mind to what people say. No, I have not betrayed the cause of liberty. But for now, it's totally essential that order be restored. But one day I will rise up—soon—and throw myself into the fight for liberty, by myself. No, I am neither fascist nor Bolshevik. I am alone!...Like Croce in Italy, I am alone![21][22]

On 21 November, he wrote to the Italian philosopher Lorenzo Giusso that "The barbarism is unanimous. It is a regime of terror on both sides."[23] In one of his final letters, dated 13 December, Unamuno, in terms that were to be widely quoted, condemned the White Terror being committed by Franco's forces:

[Franco's army] is waging a campaign against liberalism, not against Bolshevism [...] They will win, but they will not convince; they will conquer, but they will not convert.[24]

Broken-hearted, Unamuno was placed under house arrest by Franco, until his death.[25]

Confrontation with Millán Astray

[edit]On 12 October 1936, the Spanish Civil War had been underway for just under three months; the celebration of Discovery of America had brought together a politically diverse crowd at the University of Salamanca, including Enrique Pla y Deniel, the Archbishop of Salamanca, and Carmen Polo Martínez-Valdés, the wife of Franco, Africanist General José Millán Astray and Unamuno himself.

Unamuno had supported Franco's uprising because he believed it necessary to bring order to the anarchy created by the Popular Front, and that day he was representing General Franco in the event. By then the Republican Government had removed Unamuno from his perpetual rectory at the Salamanca University and the rebel government had restored him.

There are different versions of what occurred.

The Portillo/Thomas version

[edit]According to the British historian Hugh Thomas in his magnum opus The Spanish Civil War (1961), the evening began with an impassioned speech by the Falangist writer José María Pemán. After this, Professor Francisco Maldonado decried Catalonia and the Basque Country as "cancers on the body of the nation," adding that "Fascism, the healer of Spain, will know how to exterminate them, cutting into the live flesh, like a determined surgeon free from false sentimentalism."

From somewhere in the auditorium, someone cried out the Spanish Legion's motto "¡Viva la Muerte!" [Long live death!]. As was his habit, Millán Astray, the founder and first commander of the Spanish Legion, responded with "¡España!" [Spain!]; the crowd replied with "¡Una!" [One!]. He repeated "¡España!"; the crowd then replied "¡Grande!" [Great!]. A third time, Millán Astray shouted "¡España!"; the crowd responded "Libre!" [Free!] This—Spain, one, great, and free—was a common Falangist cheer and would become a francoist motto thereafter. Later, a group of uniformed Falangists entered, saluting the portrait of Franco that hung on the wall.

Unamuno, who was presiding over the meeting, rose up slowly and addressed the crowd:

You are waiting for my words. You know me well, and know I cannot remain silent for long. Sometimes, to remain silent is to lie, since silence can be interpreted as assent. I want to comment on the so-called speech of Professor Maldonado, who is with us here. I will ignore the personal offence to the Basques and Catalans. I myself, as you know, was born in Bilbao. The Bishop,

Unamuno gestured to the Archbishop of Salamanca,

whether you like it or not, is Catalan, born in Barcelona. But now I have heard this insensitive and necrophilous oath, "¡Viva la Muerte!", and I, having spent my life writing paradoxes that have provoked the ire of those who do not understand what I have written, and being an expert in this matter, find this ridiculous paradox repellent. General Millán Astray is a cripple. There is no need for us to say this with whispered tones. He is a war cripple. So was Cervantes. But unfortunately, Spain today has too many cripples. And, if God does not help us, soon it will have very many more. It torments me to think that General Millán Astray could dictate the norms of the psychology of the masses. A cripple, who lacks the spiritual greatness of Cervantes, hopes to find relief by adding to the number of cripples around him.

Millán Astray responded: "Death to intelligence! Long live death!" provoking applause from the Falangists. Pemán, in an effort to calm the crowd, exclaimed "No! Long live intelligence! Death to the bad intellectuals!"

Unamuno continued: "This is the temple of intelligence, and I am its high priest. You are profaning its sacred domain. You will win [venceréis], because you have enough brute force. But you will not convince [pero no convenceréis]. In order to convince it is necessary to persuade, and to persuade you will need something that you lack: reason and right in the struggle. I see it is useless to ask you to think of Spain. I have spoken." Millán Astray, controlling himself, shouted "Take the lady's arm!" Unamuno took Carmen Polo by the arm and left under her protection.

The Severiano Delgado version

[edit]In 2018, the details of Unamuno's speech were disputed by the historian Severiano Delgado, who argued that the account in a 1941 article by Luis Gabriel Portillo (who was not present at Salamanca) in the British magazine Horizon may not have been an accurate representation of events.

Severiano Delgado, a historian and librarian at the University of Salamanca, asserts that Unamuno's words were put in his mouth by Luis Portillo, in 1941, possibly with some help from George Orwell, in a piece in the literary magazine Horizon, entitled Unamuno's Last Lecture. Portillo had not witnessed the event.[26]

Severiano Delgado's book, titled Archeology of a Myth: The act of October 12, 1936 in the auditorium of the University of Salamanca, shows how the propaganda myth arose regarding the confrontation that took place that day between Miguel de Unamuno and the general Millán Astray.

Delgado agrees that a "very fierce and violent verbal confrontation" between Unamuno and Millán Astray definitely occurred, which led to Unamuno being removed from his rectorship, but he thinks that the famous speech attributed to Unamuno was invented and written by Luis Portillo."[27][26]

Delgado says that:

What Portillo did was to come up with a kind of liturgical drama, where you have an angel and a devil confronting one another. What he wanted to do above all was symbolise evil—fascism, militarism, brutality—through Millán Astray, and set it against the democratic values of the republicans—liberalism and goodness—represented by Unamuno. Portillo had no intention of misleading anyone; it was simply a literary evocation.

Unamuno took the floor, not to confront Millán Astray, but to answer a previous speech by Professor of Literature Francisco Maldonado who had identified Catalonia and the Basque Country with the "antiespaña" (Antispain). Unamuno himself was Basque and was revolted with Francisco Maldonado's speech, but when addressing the audience, Unamuno used the example of what had happened with José Rizal (a Filipino nationalist and polymath during the tail end of the Spanish colonial period of the Philippines, executed by the Spanish colonial government for the crime of rebellion after the Philippine Revolution). Millán Astray had fought in the Philippines and it was the reference to José Rizal that annoyed Millán Astray, who shouted "The traitoring intellectuals die".

As proof that the incident was nothing more than a crossroads of hard words, the photograph reproduced on the cover of his book shows Millán Astray and Miguel de Unamuno calmly saying goodbye in the presence of Bishop Plà, with no tension between them. The photo was discovered in 2018 in the National Library and was part of the chronicle of the act that the newspaper "The Advancement of Salamanca" published the following day, 13 October 1936.[26]

According to Delgado, Portillo's account of the speech became famous when a then very young British historian Hugh Thomas, aged 30, came across it in a Horizon anthology while researching his seminal book, The Spanish Civil War, and mistakenly took it as a primary source.[26]

Death

[edit]Unamuno died on 31 December 1936[25] during house arrest imposed by the military forces that occupied Salamanca at the time. He died as a result of the inhalation of gases from a brazier during a one hour long interview with a visitor. A recent theory cites a 2020 book by Colette Rabaté and Jean-Claude Rabaté[citation needed] to suggest that he may have been murdered by Bartolomé Aragón, the last person to have visited him, based on the fact that he falsely claimed to be a former student of his, was a fascist militant (and requeté) with opposed political ideas to Unamuno and had collaborated with Nationals propaganda before. In fact, the Rabaté couple never defended this theory, since they have no new evidence to support it.[28] These circumstances are, however, well known since the time of the events in 1936, and Aragón and Unamuno had indeed a previous intellectual relationship.[29] Additional telltale findings were: the lack of autopsy (despite having been mandatory, as the cause of death was determined to be a sudden death due to an intracranial bleeding), two screams from Unamuno heard by his maid during the Aragón visit and discrepancies in the time of death registered by the coroner and the authorities.[30][31][32]

Literary career and works

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Paz en la guerra (Peace in War) (1897) – a novel that explores the relationship of self and world through familiarity with death. It is based on his experiences as a child during the Carlist siege of Bilbao in the Third Carlist War.

- Amor y pedagogía (Love and Pedagogy) (1902) – a novel uniting comedy and tragedy in an absurd parody of positivist sociology.

- El espejo de la muerte (The Mirror of Death) (1913) – a collection of stories.

- Niebla (Mist) (1914) – one of Unamuno's key works, which he called a nivola to distinguish it from the supposedly fixed form of the novel (novela in Spanish).

- Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho (usually translated into English as Our Lord Don Quixote) (1914) – another key work of Unamuno, often perceived as one of the earliest works applying existential elements to Don Quixote. The book, on Unamuno's own admission, is of mixed genre with elements of personal essay, philosophy, and fiction. Unamuno felt that Miguel de Cervantes had not told the story of Don Quijote very well, cluttering it with unrelated tales. Unamuno intended this work to present Cervantes' story the way it should have been written. He felt that as a quijotista (a fan or student of Don Quixote) he was superior to Cervantes. The work is primarily of interest to those studying Unamuno, not Cervantes.

- Abel Sánchez (1917) – a novel that uses the story of Cain and Abel to explore envy.

- Tulio Montalbán (1920) – a short novel on the threat of a man's public image undoing his true personality, a problem familiar to the famous Unamuno.

- Tres novelas ejemplares y un prólogo (Three Exemplary Novels and a Prologue) (1920) – a much-studied work with a famous prologue. The title deliberately recalls the famous Novelas ejemplares of Miguel de Cervantes.

- La tía Tula (Aunt Tula) (1921) – his final large-scale novel, a work about maternity, a theme that he had already examined in Amor y pedagogía and Dos madres.

- Teresa (1924) – a narrative work that contains romantic poetry, achieving an ideal through the re-creation of the beloved.

- Cómo se hace una novela (How to Make a Novel) (1927) – the autopsy of an Unamuno novel.

- Don Sandalio, jugador de ajedrez (Don Sandalio, Chess Player) (1930).

- San Manuel Bueno, mártir (Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr) (1930) – a brief novella that synthesizes virtually all of Unamuno's thought. The novella centres on a heroic priest who has lost his faith in immortality, yet says nothing of his doubts to his parishioners, not wanting to disturb their faith, which he recognizes is a necessary support for their lives.

Philosophy

[edit]

Unamuno's philosophy was not systematic but rather a negation of all systems and an affirmation of faith "in itself." He developed intellectually under the influence of rationalism and positivism, but during his youth he wrote articles that clearly show his sympathy for socialism and his great concern for the situation in which he found Spain at the time. An important concept for Unamuno was intrahistoria. He thought that history could best be understood by looking at the small histories of anonymous people, rather than by focusing on major events such as wars and political pacts. Some authors relativize the importance of intrahistoria in his thinking. Those authors say that more than a clear concept, it is an ambiguous metaphor. The term first appears in the essay En torno al casticismo (1895), but Unamuno leaves it soon.[33]

Unamuno: "Those who believe they believe in God, but without passion in the heart, without uncertainty, without doubt, and even at times without despair, believe only in the idea of God, and not in God himself."[34]

In the late nineteenth century Unamuno suffered a religious crisis and left the positivist philosophy. Then, in the early twentieth century, he developed his own thinking influenced by existentialism.[35] Life was tragic, according to Unamuno, because of the knowledge that we are to die. He explains much of human activity as an attempt to survive, in some form, after our death. Unamuno summarized his personal creed thus: "My religion is to seek for truth in life and for life in truth, even knowing that I shall not find them while I live."[36] He said, "Among men of flesh and bone there have been typical examples of those who possess this tragic sense of life. I recall now Marcus Aurelius, St. Augustine, Pascal, Rousseau, René, Obermann, Thomson, Leopardi, Vigny, Lenau, Kleist, Amiel, Quental, Kierkegaard—men burdened with wisdom rather than with knowledge."[37] He provides a stimulating discussion of the differences between faith and reason in his most famous work: Del sentimiento trágico de la vida (The Tragic Sense of Life, 1912).

A historically influential paperfolder from childhood to his last, difficult days, in several works Unamuno ironically expressed philosophical views of Platonism, scholasticism, positivism, and the "science vs religion" issue in terms of "origami" figures, notably the traditional Spanish pajarita. Since he was also a linguist (professor of Greek), he coined the word "cocotología" ("cocotology") to describe the art of paper folding. After the conclusion of Amor y pedagogía (Love and Pedagogy, 1902), he included in the volume, attributing it to one of the characters, "Notes for a Treatise on Cocotology" ("Apuntes para un tratado de cocotología").[38]

Along with The Tragic Sense of Life, Unamuno's long-form essay La agonía del cristianismo (The Agony of Christianity, 1931) and his novella San Manuel Bueno, mártir (Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr, 1930) were all included on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[39]

After his youthful sympathy for socialism ended, Unamuno gravitated towards liberalism. Unamuno's conception of liberalism, elaborated in essays such as La esencia del liberalismo in 1909, was one that sought to reconcile a great respect for individual freedom with a more interventionist state, bringing him to a position closer to social liberalism.[40] In writing about the Church in 1932 during the second Spanish Republic, Unamuno urged the clergy to end their attacks on liberalism and instead embrace it as a way of rejuvenating the faith.[14]

Unamuno was probably the best Spanish connoisseur of Portuguese culture, literature, and history of his time. He believed it was as important for a Spaniard to become familiar with the great names of Portuguese literature as with those of Catalan literature. He believed that Iberian countries should come together through the exchange of manifestations of the spirit but he was openly against any type of Iberian Federalism.[41]

In the final analysis Unamuno's significance is that he was one of a number of notable interwar intellectuals, along with Julien Benda, Karl Jaspers, Johan Huizinga, and José Ortega y Gasset, who resisted the intrusion of ideology into Western intellectual life.[42]

Poetry

[edit]For Unamuno, the art of poetry was a way of expressing spiritual problems. His themes were the same in his poetry as in his other fiction: spiritual anguish, the pain provoked by the silence of God, time and death.

Unamuno was always attracted to traditional meters and, though his early poems did not rhyme, he subsequently turned to rhyme in his later works.

Among his outstanding works of poetry are:

- Poesías (Poems) (1907) – his first collection of poetry, in which he outlined the themes that would dominate his poetics: religious conflict, Spain, and domestic life

- Rosario de sonetos líricos[43] (Rosary of Lyric Sonnets) (1911)

- El Cristo de Velázquez (The Christ of Velázquez) (1920) – a religious work, divided into four parts, where Unamuno analyzes the figure of Christ from different perspectives: as a symbol of sacrifice and redemption, as a reflection on his Biblical names (Christ the myth, Christ the man on the cross, Christ, God, Christ the Eucharist), as poetic meaning, as painted by Diego Velázquez, etc.

- Andanzas y visiones españolas (1922) – something of a travel book, in which Unamuno expresses profound emotion and experiments with landscape both evocative and realistic (a theme typical of his generation of writers)

- Rimas de dentro (Rhymes from Within) (1923)

- Rimas de un poeta desconocido (Rhymes from an Unknown Poet) (1924)

- De Fuerteventura a París (From Fuerteventura to Paris) (1925)

- Romancero del destierro (Ballads of Exile) (1928)

- Cancionero (Songbook) (1953, published posthumously)

Drama

[edit]Unamuno's dramatic production presents a philosophical progression.

Questions such as individual spirituality, faith as a "vital lie", and the problem of a double personality were at the center of La esfinge (The Sphinx) (1898), and La verdad (Truth), (1899).

In 1934, he wrote El hermano Juan o El mundo es teatro (Brother Juan or The World is a Theatre).

Unamuno's theatre is schematic; he did away with artifice and focused only on the conflicts and passions that affect the characters. This austerity was influenced by classical Greek theatre. What mattered to him was the presentation of the drama going on inside of the characters, because he understood the novel as a way of gaining knowledge about life.

By symbolizing passion and creating a theatre austere both in word and presentation, Unamuno's theatre opened the way for the renaissance of Spanish theatre undertaken by Ramón del Valle-Inclán, Azorín, and Federico García Lorca.

In popular culture

[edit]- A sculpture of Unamuno's head by Victorio Macho was installed in the City Hall of Bilbao, Spain. It was withdrawn in 1936 when Unamuno showed temporary support for the Nationalist side. During the Spanish Civil War, it was thrown into the estuary. It was later recovered. In 1984 the head was installed in Plaza Unamuno near his birthplace. In 1999, it was again thrown into the estuary after a political meeting of Euskal Herritarrok. It was substituted by a copy in 2000 after the original was located in the water. The original was installed in the mayor's office.[44][45][46]

- In 2021, United States–based jazz pianist and composer Dave Meder published an album of original music inspired by Unamuno's life and writing, entitled Unamuno Songs and Stories.

- In the 2015 documentary La isla del viento, directed by Manuel Menchón, Unamuno is played by José Luis Gómez and his 1924 exile in Fuerteventura due to his critics to Primo de Rivera is depicted.[47]

- The 2019 film While at War shows Unamuno (played by Karra Elejalde) between 18 July 1936 and his death.[48]

- In the TV series Star Trek: Picard, the pilot Chris Rios has a book copy of The Tragic Sense of Life on the ship's dashboard.[49]

- The climax of the fiction (and meta-fiction) The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (Editorial Caminho, Lisboa, Portugal, 1984; English translation, HarcourtISBN 978-0-15-199735-0, 1991) by José Saramago features a report of the famous Salamanca argument with Milan d'Astray, but seen from a Portuguese perspective.

See also

[edit]- Thinking about the immortality of the crab

- Rafael Moreno Aranzadi – his nephew, footballer also known as Pichichi[50]

References

[edit]- ^ "'The Tragic Sense of Life', by Miguel de Unamuno". gutenberg.org. Retrieved 27 August 2015 – via Project Gutenbert.

- ^ Abel Sánchez by Miguel de Unamuno. Retrieved 27 August 2015 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Miguel de Unamuno, Niebla [Mist]". www.litencyc.com. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Rabaté & Rabaté 2009, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Conversi, Daniele (1997). The Basques, the Catalans, and Spain: alternative routes to nationalist mobilisation. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-1850652687.

- ^ Ramsden, H. (1974). "The Spanish ?Generation of 1898?: I. The history of a concept". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 56 (2). Manchester, UK: John Rylands University Library, Manchester: 463–91. ISSN 0301-102X.

- ^ Azurmendi, Joxe: Espainiaren arimaz, 2006. pp. 101–46. Azurmendi adds that Unamuno analyzed and rejected the Basque problem from a 19th century point of view

- ^ Harrison, Joseph; Hoyle, Alan (2000). Spain's 1898 Crisis: Regenerationism, Modernism, Postcolonialism. Manchester University Press. p. 73.

- ^ Unamuno, Miguel de (1 September 1924). "Conferencia en "La Sociedad El Sitio"". El Socialista.

- ^ Evans, Jan E. (2014). Miguel de Unamuno's Quest for Faith: A Kierkegaardian Understanding of Unamuno's Struggle to Believe. James Clarke & Co. p. 116.

- ^ Schmitt, Hans A. (1988). Neutral Europe Between War and Revolution, 1917–23. University of Virginia. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Cobb, Christopher (1976). Artículos Olvidados Sobre España y la Primera Guerra Mundial. Tamesis. pp. ix–1.

- ^ "Casa museo Miguel de Unamuno en Fuerteventura". Absolut Lanzarote. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ a b Evans, Jan E. (2013). Miguel de Unamuno's Quest for Faith: A Kierkegaardian Understanding of Unamuno's Struggle to Believe. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 121.

- ^ Hayes, Carlton (1951). The United States and Spain. An Interpretation. Sheed & Ward; 1ST edition. ASIN B0014JCVS0.

- ^ Rabaté & Rabaté 2009.

- ^ Broué, Pierre; Témime, Emile (2008). The Revolution and Civil War in Spain. Haymarket Books. p. 440. ISBN 978-1931859516.

- ^ Blanco-Prieto F. (2011). "Unamuno y la Guerra Civil". Cuadernos de la Cátedra Miguel de Unamuno. 47 (1): 13–53.

- ^ Graham, Helen (2005). The Spanish Civil War: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0192803771.

- ^ Helen Graham (24 March 2005). The Spanish Civil War: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780192803771.

- ^ Toledano, Ana Chaguaceda (2003). Miguel de Unamuno, estudios sobre su obra, Volume 4. Universidad de Salamanca. p. 131.

No, no me he convertido en un derechista. No haga usted caso de lo que dice la gente. No he traicionado la causa de la libertad. Pero es que, por ahora, es totalmente esencial que el orden sea restaurado. Pero cualquier día me levantaré—pronto—y me lanzaré a la lucha por la libertad, yo solo. No, no soy fascista ni bolchevique. ¡Estoy solo!...¡Solo, como Croce in Italia!

- ^ Litvak de Kravzov, Lily (January 1967). "Nikos Kazantzakis y España". Hispanófila. 29: 37–44.

- ^ García de Cortázar, Fernando (2005). Los mitos de la Historia de España. Planeta Pub Corp. pp. 294–95.

- ^ Unamuno, Miguel de (1991). Epistolario inédito II (1915–1936). Espasa Calpe. pp. 354–55. ISBN 978-8423972395.

- ^ a b Antony, Beevor (2006). The Battle for Spain. London: Phoenix. pp. 111–13.

- ^ a b c d Delgado Cruz 2019.

- ^ Jones, Sam (11 May 2018). "Spanish civil war speech invented by father of Michael Portillo, says historian". The Guardian.

- ^ "Rabaté, biógrafo de Unamuno: "Hay dudas sobre su muerte, pero faltan pruebas"". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 23 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Bartolomé Aragón, el eterno y "altamente improbable" sospechoso en la muerte de Unamuno". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 23 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Cortés, Iker (12 November 2020). "Los últimos años de Unamuno". El Correo (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ García, Fernando (23 October 2020). "Un documental agita la historia al desmontar la versión oficial de la muerte de Unamuno". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Herrero, Julián (23 October 2020). "Bartolomé Aragón, el testigo de las últimas palabras de Unamuno". La Razón (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Azurmendi, Joxe: Espainiaren arimaz, 2006. p. 90.

- ^ Quoted in Madeleine L'Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art (New York: Bantam Books, 1982), 32.

- ^ Azurmendi, Joxe: "Unamunoren atarian" in: Alaitz Aizpuru, Euskal Herriko pentsamenduaren gida, 2012. p. 40.

- ^ Miguel de Unamuno, "Mi religión" (1907)

- ^ Tragic Sense Of Life, I The Man Of Flesh And Bone

- ^ For a bird-figure folded by him in November 1936, see Vicente Palacios, Papirogami: Tradicional Arte del Papel Plegado (Barcelona: Miguel Salvatella, 1972), p. 122.

- ^ John A. Mackay, The Meaning of Life: Christian Truth and Social Change in Latin America (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014), p. 158.

- ^ Harrison, Joseph; Hoyle, Alan (2000). Spain's 1898 Crisis: Regenerationism, Modernism, Postcolonialism. Manchester University Press. p. 73.

- ^ Morejón, Julio García (29 September 1962). "Iberismo unamuniano". Revista de História. 25 (51): 87–123. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.1962.121686.

- ^ Sean Farrell Moran, "The Disease of Human Consciousness," in Oakland Journal, 12, 2007, 103–10.

- ^ Unamuno, Miguel. "Rosario de sonetos liricos". archive.org. Madrid: Imprenta Espanola. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Uriona, Alberto (6 March 2000). "El Ayuntamiento de Bilbao restituye a su columna el busto de Unamuno nueve meses después de su robo". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Camacho, Isabel (9 June 1999). "La cabeza perdida de don Miguel". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Victorio Macho y Unamuno: notas para un centenario" (PDF) (in Spanish). Real Fundación Toledo. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Unamuno, una muerte manipulada. El documental ‘Palabras para un fin del mundo’ cuestiona el relato oficial sobre el fallecimiento del escritor y el papel que jugó el falangista que le visitó en su casa, El País, 23 de octubre de 2020

- ^ "While at War". Toronto International Film Festival. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (13 February 2020). "'Star Trek: Picard': Rios' Book Inspires Intriguing Theory About the Pilot". Heavy.com. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "Opinión: 'Pichichi', de Hugo a Chicharito" [Opinion: 'Pichichi', from Hugo to Chicharito] (in Spanish). Goal.com. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Álvarez, José Luis. 1966: "Unamuno ala Jammes?", Jakin, 21: 81–84.

- Azurmendi, Joxe. 2006: "Unamuno" in Espainiaren arimaz, Donostia: Elkar. ISBN 849783402X

- Azurmendi, Joxe. 2012: Bakea gudan. Unamuno, historia eta karlismoa, Tafalla, Txalaparta. ISBN 978-8415313199

- Azurmendi, Joxe. 2012: "Unamunoren atarian" in Alaitz Aizpuru (koord.), Euskal Herriko pentsamenduaren gida, Bilbo, UEU. ISBN 978-8484384359

- Blazquez, Jesus, ed. (2010). Unamuno y Candamo: Amistad y Epistolario (1899–1936) (in Spanish). Ediciones 98 S.L.

- Candelaria, Michael, The Revolt of Unreason. Miguel de Unamuno and Antonio Caso on the Crisis of Modernity. Edited and with a foreword by Stella Villarmea. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2012. ISBN 978-9042035508

- Delgado Cruz, Severiano (2019). Arqueología de un mito: el acto del 12 de octubre de 1936 en el paraninfo de la Universidad de Salamanca (in Spanish). Sílex Ediciones; Edición. ISBN 978-8477378723.

- Pedro Blas González, "Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Floricanto Press, 2007."

- Pérez, Rolando. “Karl Jaspers and Miguel de Unamuno on Reason in an Age of Irrationality.” Existenz: An International Journal in Philosophy, Religion, Politics, and the Arts. Vol. 15. No. 2. PDF: pp. 32–39. https://existenz.us/volumes/Vol.15-2Perez.html

- Rabaté, Jean-Claude; Rabaté, Colette (2009). Miguel de Unamuno: Biografía (in Spanish). Taurus.

- Sáenz, Paz, ed. (1988). Narratives from the Silver Age. Translated by Hughes, Victoria; Richmond, Carolyn. Madrid: Iberia. ISBN 8487093043.

- Sean Farrell Moran, "The Disease of Human Consciousness," in Oakland Journal, 12, 2007, 103–10

- Salcedo, Emilio (1998). Vida de don Miguel: Unamuno, un hombre en lucha con su leyenda (in Spanish) (1.. Anthema, 3.. del autor (corr.) ed.). Anthema Ediciones. ISBN 978-8492243747.

- Portillo, Luis (1941). "Unamuno's Last Lecture". Horizon: A Review of Literature and Art. December: 394–400.

External links

[edit]- Biography, images and curiosities of Unamuno

- Works by Miguel de Unamuno at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Miguel de Unamuno at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Miguel de Unamuno at the Internet Archive

- Works by Miguel de Unamuno at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Video: Joxe Azurmendi on Unamuno

- Dossier on Unamuno Jakin magazine

- Concordances of Unamuno's Poetry

- Dios te está soñando La narración como Imitatio Dei en Miguel de Unamuno por Costica Bradatan

- Newspaper clippings about Miguel de Unamuno in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Miguel de Unamuno

- 1864 births

- 1936 deaths

- 19th-century Spanish philosophers

- 20th-century Spanish philosophers

- Basque academics

- Basque writers

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Former Roman Catholics

- Members of the Royal Spanish Academy

- Origami artists

- Writers from Bilbao

- Philosophers of pessimism

- Spanish agnostics

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish dramatists and playwrights

- Spanish male dramatists and playwrights

- Spanish essayists

- Basque novelists

- Spanish male novelists

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War

- Spanish poets

- Spanish male poets

- Spanish republicans

- Modernist writers

- Spanish Anti-Francoists

- Spanish anti-fascists

- FET y de las JONS politicians

- Spanish male essayists

- 19th-century essayists

- 20th-century Spanish essayists

- Academic staff of the University of Salamanca