Islamic Army of the Caucasus

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Azerbaijani. (July 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Islamic Army of the Caucasus | |

|---|---|

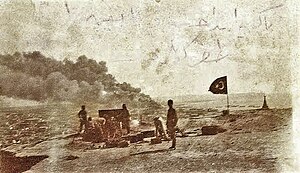

Ottoman artillery bombarding Baku | |

| Active | July 10, 1918[1] – October 27, 1918[2] |

| Country | |

| Type | Corps (although named as an army) |

| Size | 20,000 soldiers (Turks, Azerbaijanis, Dagestanis and Chechens) |

| Part of | Eastern Army Group |

| Garrison/HQ | Yelizavetpol, Baku |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Ceremonial chief | Enver Pasha |

| Notable commanders | Nuri Pasha (Killigil) |

The Islamic Army of the Caucasus (Azerbaijani: Qafqaz İslam Ordusu; Turkish: Kafkas İslâm Ordusu) (also translated as Caucasian Army of Islam in some sources) was a military unit of the Ottoman Empire formed on July 10, 1918.[1] The Ottoman Minister of War, Enver Pasha, ordered its establishment,[1] and it played a major role during the Caucasus Campaign of World War I.

Background

[edit]During 1917, due to the Russian Revolution and subsequent Civil War, the Russian army in the Caucasus ceased to exist. The Russian Provisional Government's Caucasus Front formally ceased to exist in March 1918. Meanwhile, the Committee of Union and Progress moved to win the friendship of the Bolsheviks by signing the Ottoman-Russian friendship treaty (January 1, 1918). On January 11, 1918, the special decree On Armenia was signed by Lenin and Stalin which armed and repatriated over 100,000 Armenians from the former Tsar's Army to be sent to the Caucasus for operations against Ottoman interests.[3] On January 20, 1918, Talaat Pasha entered an official protest against the Bolsheviks arming Armenian army legions and replied, "the Russian leopard had not changed its spots."[3] Bolsheviks and Armenians would take the place of Nikolai Nikolayevich Yudenich's Russian Caucasus Army.[4]

The exclusion of German officers from the Caucasian Army of Islam was deliberate. By the end of 1917, Enver Pasha concluded that the Germans and the Ottoman Empire did not have compatible goals after the Russian Empire had collapsed. This feeling was confirmed by the terms of the treaty of Treaty of Brest-Litovsk which was very favorable to the Germans and overlooked the goals of the Ottomans. Enver looked for victory where Russia left in the Caucasus. When Enver discussed his plans for taking over southern Russia, the Germans told him to keep out[citation needed].

On 22 April 1918, the Transcaucasian Commissariat in Tiflis adopted a declaration of independence, proclaiming the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Delegates from the Republic and from the Ottoman Empire held the Trebizond Peace Conference to establish their borders.[a] During March 30 to April 2 in 1918, thousands of Azerbaijanis and other Muslims in the city of Baku and adjacent areas of the Baku Governorate of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic were massacred by Dashnaks with strong support from Bolshevik Soviets. The Azerbaijanis refer to this as a genocide (Azerbaijani: soyqırım). This event is known as the March Days or March Events. On April 5, 1918, both sides at the Trebizond Peace Conference agreed that a state of war exists.

By June 4, 1918, the Ottoman 3rd Army had advanced to within 7 km of Yerevan and 10 km of Echmiadzin which led to the Treaty of Batum but was subsequently repelled by the Armenians.[b] The Ottoman's 3rd Army had secured the Ottoman Empire's pre war borders.

During late spring 1918, Bolsheviks in Moscow sent oil from Baku over the Caspian Sea and up the lower Volga to Austrian-German forces in Ukraine in return for German financial support and German help to stop the Ottoman 3rd Army's advances through Armenian territory and into the Caucasus.[3][8] The 3rd Army's objective was to take and occupy the railroad and pipeline which ran from Batumi through Tiflis to Baku.[3] Later, the Bolsheviks through the May 28th Treaty of Poti recognized Georgia's independence under German control and allowed Germany to have 25% of the oil from Baku.[3] The Bolsheviks wanted Germany to prevent the 3rd Ottoman Army from taking the railroad and pipeline.[3] Subsequently, Erich Ludendorff in the German High Command sent forces to Georgia under Kress.[c][3]

After several skirmishes between the Ottoman 3rd Army and the German forces near Vorontsovka, the German High Command objected and informed its Ottoman ally that Germany would withdraw its troops and support from the Ottoman Empire.[3] Erich Ludendorff sent Hans von Seeckt to Batumi to confer with Enver Pasha about the situation.[3] This led to Vehip Pasha being sacked from the head of the Ottoman 3rd Army.[3] The Ottoman Empire's objective shifted from taking the railroad and pipeline to taking and occupying Baku and its nearby oilfields.[3][8]

The purpose of the Caucasus Army of Islam was to mobilize Muslim supporters in Transcaspian and Caucasian regions.[1] Nuri Pasha came to Yelizavetpol (present day: Ganja) on May 25, 1918 and began to organize the Army of Islam.[9]

Order of Battle, 1918

[edit]- Islamic Army of the Caucasus Headquarters (Yelizavetpol, Baku)

- Commander: Mirliva and Fahri (honorary) Ferik Nuri Pasha

- Chief of Staff: Kaymakam Edip Bey

- Staff: First Lieutenant Asaf Efendi (Kılıç Ali)

- Staff: First Lieutenant Muzaffer Efendi

- Chief of the division of operations: Binbaşı Tevfik Bey

- Staff: Binbaşı Naim Bey

- Officer at HQ: Yüzbaşı Sami Bey

- Artillery officer: Binbaşı Kemal Bey

- Inspector: Kaymakam Şefik Bey

- Adviser: Ağaoğlu Ahmet

- 5th Caucasian Infantry Division (commanded by Miralay Mürsel Bey, as reinforcement from II Corps of Third Army[10])

- 9th Caucasian Infantry Regiment

- 10th Caucasian Infantry Regiment

- 13th Caucasian Infantry Regiment

- 56th Infantry Regiment

- 15th Infantry Division (commanded by Kaymakam Süleyman Izzet Bey[11])

- 38th Infantry Regiment

- 106th Caucasian Infantry Regiment

Operations

[edit]Azerbaijan

[edit]

With the march of an Ottoman supported army to Baku, the Bolshevik soviet fled to Astrakhan which left Baku to be defended by SRs, Armenians, and, later, the British General Dunsterville's force of 1,000.[3]

Chief of the British Military Mission to the Caucasus Major General Lionel Charles Dunsterville reached Bandar-e Anzali in mid-February and organized a small military force called "Dunsterforce" of Cossacks, Russians and Azeris. The British authority were concerned about an advance of either the Germans or the Ottoman forces to the Baku oil fields and began to send reinforcements to the "Dunsterforce" in June 1918.[12] Although most of the oil fields were owned by Azerbaijanis and less than 5 per cent by Armenians, most of the production/distribution rights in Baku were owned by foreign investors, primarily the British.[13]

The Islamic Army of the Caucasus began to attack Hill 905 on July 31 to the northwest of Baku, but failed to get the hill and halted their attack on August 2. Major General L.C. Dunsterville coordinated future combined operations with the Cossack forces commended by Colonel Lazar Bicherakhov, and sent about 300 British soldiers to Baku and they arrived there on August 5. The Islamic Army of the Caucasus launched second attack to Hill 905 on August 5. This attack failed again and they lost 547 officers and soldiers.[12]

The last attack of the Islamic Army of the Caucasus on Baku began at 1:00 A.M. on September 14. The Ottoman 15th Division attacked from the north and the 5th Caucasian Division attacked from the west. British Major General Dunsterville decided to withdraw about 11:00 A.M. because of the failure of the defense. "Dunsterforce" loaded its personnel and equipment and set sail for Bandar-e Anzali by 10:00 P.M. on September 14.[14]

The Army of Islam took Baku on September 15 and sent a telegraph announcing the capture of Baku to Enver Pasha on September 16.[14]

North Caucasus

[edit]The Islamic Army of the Caucasus sent the 15th Division to North Caucasus after its reorganization. The 15th Division advanced northwards along the Caspian coast, encountered the local resistance in front of Derbent and spotted advance on October 7. The division restarted attack on Derbent on October 20 and occupied the city on October 26. The division continued to advance northwards and arrived at the gate of Petrovsk (present day: Makhachkala) on October 28 and occupied the city on November 8.[14]

Aftermath

[edit]First, Enver Pasha's gambit of taking Baku's oilfields failed when British forces advanced in Syria and also when Bulgaria capitulated to the Entente Powers in September 1918: the Ottoman Empire had few forces to defend either Syria or Constantinople. This allowed Franchet d'Espèrey's Allied Army of the Orient along with Milne's Army at Salonika to occupy western Thrace within a short march to Constantinople leading to the Armistice of Mudros.[3] The British Fleet could sail the Dardanelles.[3] The Ottoman's forces had to withdraw from Baku allowing the Bolsheviks to regain not only the control of the oil fields but also the money gained from oil sales.[3]

Second, the subsequent withdrawal of Austrian and German support from Southern Russia and the Caucasus along with the Turkish War of Independence placed the British and French at odds with their foreign policy toward both the Turks and the Russians. Because the British and French supported the Greeks and Armenians in their fight against the Turks, the Turks were kept from occupying the Baku oilfields during the Russian Civil War. This allowed the Bolsheviks to gain capital from the Baku oilfields which would be used in the destruction of the British and French supported anti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

Third, neither pan-Turkism nor pan-Turanianism would receive support through a large army from Turkey again.[3][8]

Finally, prior to the summer of 1918, Germany had unabashed support for a Zionist state which would have allowed Germany to gain railroad and pipeline concessions between the Levant[d] and the oil rich Persian Gulf. This was all part of its Drang nach Osten. Instead, Germany shifted its foreign policy support to Islamic forces in obtaining guarantees of oil supplies from Southern Russia and Persia via Batumi, Tiflis, and Baku, thus splitting its foreign policy goals from those of Turkey and removing German support for Zionism.[3]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Both the delegates from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic and the delegates from the Ottoman Empire agreed that the borders from the Brest-Litovsk were incorrect.

- ^ The Ottoman 3rd Army had lost the Battle of Sardarapat (May 21–29), the Battle of Kara Killisse (1918) (May 24–28), and the Battle of Bash Abaran (May 21–24)[5][6][7]

- ^ Kress had been involved in supporting Ottoman 8th Army interests near the Suez in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign.

- ^ Palestine, which is in the Levant, was the German supported location of the Zionist state which is now known as Israel.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Order to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Greenwoodpress. p. 189. ISBN 0-313-31516-7.

- ^ Türkmen, Zekeriya (2001). Mütareke Döneminde Ordunun Durumu ve Yeniden Yapılanması (1918-1920) [Condition and Restructuring of the Army in the Armistice Period (1918-1920)] (in Turkish). Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 31. ISBN 975-16-1372-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q McMeekin, Sean (2010). The Berlin-Baghdad Express: Ottoman Empire and Germany's bid for World Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674057395.

- ^ McMeekin, Sean (October 13, 2015). The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908 - 1923. Penguin. ISBN 9780698410060.

- ^ Balakian, Peter (2003). The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. New York: HarperCollins. p. 321. ISBN 0-06-055870-9.

- ^ Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia The Survival of a Nation (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 0-7099-0210-7.

- ^ Afanasyan, Serge (1985). La victoire de Sardarabad: Arménie, mai 1918 [The Victory of Sardarabad: Armenia, May 1918] (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Michael A. (May 2009). "Buffers, not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in the First World War and the Myth of Panturanism". 2003. Past and Present.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kurter, Ajun (2009). Türk Hava Kuvvetleri Tarihi [Turkish Air Force History] (in Turkish). Vol. IV (3rd ed.). Türk Hava Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı. p. 92.

- ^ Nâsir Yücer, Birinci Dünya Savaşı'nda Osmanlı Ordusu'nun Azerbaycan ve Dağıstan Harekâtı: Azerbaycan ve Dağıstan'ın Bağımsızlığını Kazanması, 1918, Genelkurmay Basım Evi, 1996, ISBN 978-975-00524-0-8, p. 75. (in Turkish)

- ^ Nâsir Yücer, Birinci Dünya Savaşı'nda Osmanlı Ordusu'nun Azerbaycan ve Dağıstan Harekâtı: Azerbaycan ve Dağıstan'ın Bağımsızlığını Kazanması, 1918, p. 177. (in Turkish)

- ^ a b Edward J. Erickson, Order to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-31516-7, p. 191.

- ^ Soviet Russia. Russian Soviet Government Bureau. 1920. p. 236.

- ^ a b c Edward J. Erickson, Order to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War, p. 192.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace, pp. 354–355. Avon Books.

- Süleyman İzzet, Büyük Harpte (1334-1918) 15. Piyade Tümeninin Azerbaycan ve Şimali Kafkasyadaki Harekât ve Muharebeleri, Askerî Matbaa, 1936 (in Turkish).

- Rüştü Türker, Birinci Dünya Harbi'nde Bakû yollarında 5 nci Kafkas Piyade Tümeni, Genelkurmay Askerî Tarih ve Stratejik Etüt Başkanlığı, 2006 (in Turkish).

External links

[edit]- Süleyman Gündüz, Kafkas İslam Ordusu Archived 2012-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, Documentary, TRT.

- 1918 in Azerbaijan

- 1918 in Armenia

- History of Dagestan

- Expeditionary Forces of the Ottoman Empire

- Military units and formations of the Ottoman Empire in World War I

- Military units and formations of the Russian Civil War

- Islam in the Caucasus

- Armenia in the Russian Civil War

- Azerbaijan in the Russian Civil War

- Enver Pasha

- Turkish involvement in the Russian Civil War