Origins of the Anglophone Crisis

The Anglophone Crisis, an ongoing civil war between the Cameroonian state and Anglophone separatists who are trying to establish a new state called "Ambazonia", broke out due to grievances which built up within Cameroon at large and its English-speaking parts specifically over several decades.

History

[edit]Early colonisation and German Kamerun

[edit]

European traders from several nations visited Ambas Bay beginning with the Portuguese in the 1470s. The first permanent European settlement on the mainland in the region was founded in 1858 by British Baptist Missionary Alfred Saker as a haven for freed slaves. This settlement which was later named Victoria (now Limbe, Cameroon) after the then Queen Victoria. Until the 1880s, European activity was dominated by trading companies and missionaries. However, in the 1880s, the Scramble for Africa reached full swing with European powers rushing to gain diplomatic or military control over Africa to secure colonial claims. The Germans, who had established substantial trading centers to the southeast on the Wouri River delta (modern Douala), and the British, who had extensive interests to the west in Nigeria, both raced to sign agreements with local rulers. German explorer Gustav Nachtigal signed key treaties with several prominent kings. Dissatisfaction with these agreements led to the brief Douala War in 1884, in which Germany assisted its local allies in winning, essentially cementing its colonial position in Cameroon and by 1887 Britain had abandoned its claims in the region.[1][2]

Germany continued to consolidate its control over the coast through agreements with local leaders backed up by military expeditions. Germany conquered Buea in 1891 after several years of fighting, transferring the colonial capital there in 1892 from Douala. By 1914, the Germans had established control either directly or through local leaders well into the hinterlands of the territory now claimed by Ambazonia, conquering communities such as Nkambe and establishing a garrison fort at Bamenda in 1912. However, many towns and villages in the hinterlands had no German administration and may have only seen German soldiers a handful of times. German administration was focused on establishing plantations for cash crops, and improving transportation and communication infrastructure to bring products and natural resources swiftly to ports and thence to Europe. The rough terrain of the Cameroon line and the lack of navigable rivers in much of the interior of the region claimed by Ambazonia limited colonial activity outside the coastal regions.

British colonial period (1914–1961)

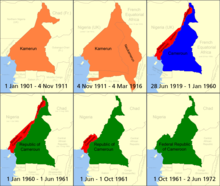

[edit]In 1914, as World War I began, British forces from British Nigeria and French forces from French Equatorial Africa and Gabon attacked German Kamerun. Allied naval superiority allowed the swift capture of the Cameroonian coast, cutting the Germans off from reinforcement or resupply. In early 1916, the last Germans surrendered or withdrew from Cameroon into neutral Spanish Guinea. In 1919, Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles, formally surrendered its colonies to the Allies. A few weeks later, Britain and France issued a statement known as the Simon-Milner Declaration, delineating the frontiers between the British Cameroons and French Cameroon.[3] This boundary was recognized internationally in 1922 and Britain and France were given control of their respective regions as League of Nations Mandates.[4]

The British Cameroons Administration Ordinance, 1924 divided British Cameroons into the Northern Cameroons (administered as part of Northern Nigeria) and the Southern Cameroons (administered as part of Eastern Nigeria). When the League of Nations mandate system was transmuted into the UN trusteeship system in 1946, this arrangement was again provided for in the Order-in-Council of 2 August 1946 providing for the administration of the Nigeria Protectorate and Cameroons under British mandate.[5] In 1953, the Southern Cameroons representatives in the Eastern Nigerian Legislature demanded a separate regional government for the Southern Cameroons with seat in Buea. Under the Lyttleton Constitution of Nigeria in 1954, Southern Cameroons gained limited autonomy as a Quasi-Region within the Nigerian Federation. E.M.L. Endeley emerged as leader of the Quasi-Region of Southern Cameroons, with his official title being Leader of Government Business.[6]

In 1957, United Nations Resolutions 1064 (XI) of 26 Feb 1957 and 1207 (XII) of Dec 13, 1957 called on the Administering Authorities to hasten arrangements for Trust territories to attain self-governance or independence. In 1958, the Southern Cameroons attained the status of a full autonomous region of the Nigerian Federation and Endeley's official title accordingly changed to Premier.[7] Despite calls by Southern Cameroons leaders for full independence as a separation nation, United Nations' resolutions 1350 (XIII) of March 13, 1959 and 1352 (XIV) of October 16, 1959 called for plebiscites in Southern Cameroons and Northern Cameroons with two alternatives for ending the trusteeship: joining Nigeria or joining Cameroon.[8]

Independence and the plebiscite (1961)

[edit]

Despite calls by Southern Cameroons leaders for full independence, United Nations' resolutions 1350 (XIII) of March 13, 1959 and 1352 (XIV) of October 16, 1959 called on Britain, the Administering Authority to organize separate plebiscites in Southern Cameroons and Northern Cameroons under UN supervision based on the following two 'alternatives': independence by joining Nigeria or joining Cameroon.[8] Two reports by British economists, the Phillipson Report in 1959 and the Berrill Report in 1960 both concluded that Southern Cameroons would not be able to continue to finance development and growth as an independent state.[9] The United Nations initiated discussions with French Cameroun on the terms of association of Southern Cameroons if the outcome of the plebiscite was in favour of a federation of the two countries.[10][11][12] While many Southern Cameroonians resented the lack of an independence option, the disappointment with Nigerian administration which had fed the push for further autonomy and hope that a more equal federation could be had with Cameroon led to a majority in favour of "reunification" with Cameroon.[13]

On 21 April 1961, UN resolution 1608 (XV) set 1 October 1961 as the date of independence for the Southern Cameroons.[14] In July 1961, the Southern Cameroons and the French Cameroon Republic delegations met in Foumban, a town in French Cameroon near the border with Southern Cameroons. The South Cameroons delegation lacked much leverage as the interests of the UN and colonial powers were to expedite the unification rather than guarantee the autonomy of Southern Cameroons.[15] The result was a constitution that provided for a federal structure with two constituent states,[16] East Cameroon (former French Cameroon) and West Cameroon (former Southern Cameroons), but which gave power over most critical issues to the national government (dominated by Francophones). One critical concession was to require that laws applying to both states could only be adopted by the federal assembly if a majority of deputies in both federated states vote for them.[15] At the time, the people of former British Cameroon expected that the future state would provide "sufficient political and cultural autonomy".[17]

Federal Republic of Cameroon and 1972 Constitution (1961–1972)

[edit]

In 1961, the government of Cameroon, with continuing assistance from France, was fighting a civil war against remnants of pro-independence fighters still dissatisfied with continued French influence in Cameroon or hoping to overthrow the pro-Western government and implement a Marxist program. President Ahmadou Ahidjo used the continuing war and the vagueness of many provisions of the Constitution, to consolidate power. In 1962, he arrested and imprisoned a number of prominent (Francophone) political opponents on charges of subversion and criticizing the state. In 1966, he succeeded in banning opposition political parties, establishing a one-party state. During this time, West Cameroonian leaders were critical of efforts to decrease their autonomy through expanded assertions of federal authority by Francophone administrators in West Cameroon. Anglophones also resented the introduction of bilingual schools in West Cameroon as an attempt to assimilate Anglophones.[18]

After achieving near total control over East Cameroon, in spring 1972 president Ahidjo targeted the autonomous powers of West Cameroon. Placing the blame for Cameroon's underdevelopment and poorly implemented public policies on the federal structure and arguing that managing separate governments in a poor country was too expensive, he announced a referendum on a new constitution, which did away with the federal structure in favor of a unitary state and granted more power to the President. The referendum was held on 20 May 1972 and in the one-party state, the outcome was never in doubt. Official results claimed 98.2% turnout and 99.99% of votes in favor of the new constitution.[19] Ambazonian nationalists have claimed that the referendum was not free and fair.[20] They have additionally argued that the new constitution was legally invalid since changes to the 1961 Constitution required approval from a majority of members of the Federal Assembly (legislature) and from each of the two constituent states, and that the new constitution was never approved by a majority of West Cameroonian legislators.[15] Along with the new constitution, the country's name was changed from 'Federal Republic of Cameroon' to the 'United Republic of Cameroon'. West Cameroon was divided into two administrative regions, which survive today: the "North West" and "South West" regions.[21] From 1972, the Anglophone territories of Cameroon became subject to increased centralisation and cultural assimilation, much to the locals' dissatisfaction.[17]

Unitary state and growing Anglophone discontent (1972–2015)

[edit]In 1975, the government removed one of the two stars from the flag, another symbol of the federation between two states, creating a new flag with a single star.[22] On 6 November 1982, Ahidjo resigned and handed over power to Paul Biya who continued Ahidjo's policies and, after a falling out with Ahidjo and attempted coup by Ahidjo supporters, consolidated power in himself.[23] In February 1984, Biya changed the official name of the country from the United Republic of Cameroon – the name adopted after unification with the Southern Cameroons – back to the Republic of Cameroon.[24] Biya stated that he had taken the step to affirm Cameroon's political maturity and to demonstrate that the people had overcome their language and cultural barriers but many in Southern Cameroons saw it as yet another step to erase their separate culture and history.

From the mid-1980s, the break between the Southern Cameroon elites and the Francophone-dominated central government became increasingly apparent. Political exclusion, economic exploitation and cultural assimilation were criticized more and more openly. In early 1985, Anglophone lawyer and President of the Cameroon Bar Association Fon Gorji Dinka circulated a number of essays and pamphlets arguing that the Biya government was unconstitutional and calling for an independent state, the "Republic of Ambazonia". The name "Ambazonia" was an attempt to break away from both Francophone as well as colonialist concepts. Gorji Dinka became the first head of the Ambazonia Restoration Council. In May 1985, he was arrested, imprisoned, and then put under house arrest for three years before escaping first to Nigeria and then to the United Kingdom.[25][17]

In 1990, opposition political parties were legalized and John Ngu Foncha, the leading Anglophone in Cameroon's government, resigned from the governing party and encapsulated much of the dissatisfaction with the central government's attitude toward the Anglophone regions in his public resignation letter:

[I]t became clear to me that I had become an irrelevant nuisance that had to be ignored and ridiculed. I was to be used now only as window dressing and not listened to. I am most of the time summoned to meetings by radio without any courtesy of my consultation on the agenda. All projects of the former West Cameroon I had either initiated or held very dear to my heart had to be taken over, mismanaged and ruined, e.g. Cameroon Bank, West Cameroon Marketing Board, WADA in Wum, West Cameroon Cooperative Movement. Whereas I spent all my life fighting to have a deep sea port in Limbe(Victoria) developed, this project had to be shelved and instead an expensive pipeline is to be built from SONARA in Limbe to Douala in order to pipe the oil to Douala. All the roads in West Cameroon my government had either built, improved or maintained were allowed to deteriorate making Kumba-Mamfe, Mamfe-Bamenda, Bamenda-Wum-Nkambe, Bamenda-Mom inaccessible by road. Projects were shelved even after petrol produced enough money for building them and the Limbe sea port. All progress of employment, appointments, etc. meant to promote adequate regional representation in government and its services have been revised or changed at the expense of those who stood for TRUTH and justice. They are identified as "Foncha-man" and put aside. The Southern Cameroonians whom I brought into the Union have been ridiculed and referred to as "les Biafrians" (Biafrans), "les enemies dans la maison" (enemies within the house), "les traitres' (traitors), etc., and the constitutional provisions which protected this Southern Cameroonian minority have been suppressed, their voices drowned while the rule of the gun has replaced the dialogue which Southern Cameroonians cherish very much. ...

— John Ngu Foncha, Resignation Letter from the CPDM party (1990)

In 1993, the "All Anglophone Conference" took place in Buea bringing together all Southern Cameroons citizens who called for the restoration of the federal system.[26] At a second All Anglophone Conference held in Bamenda the call for the Cameroon government to accept a return to the two state federation was reiterated with some voices explicitly calling for secession. In 1995, over the objection of some Anglophone Cameroonians, Cameroon was admitted to the Commonwealth of Nations recognizing former Southern Cameroon's history as a British colony. During this period various independence and federalist factions joined to form the Southern Cameroons National Council, a pressure group which undertook initiatives at the UN, the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights, the Commonwealth, and with national embassies to bring attention to the region and Anglophone issues in Cameroon. In 2005, the Southern Cameroons/Republic of Ambazonia became a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) it was renewed in 2018.[27][28] Due to harassment and arrests by the government, many leaders of he SCNC and other organizations fled the country.[13] Both 1999 and 2009 saw symbolic declarations of independence by Ambazonian nationalists, which led to arrests but little concrete action.[15] In general, the SCNC and other non-violent groups could not contain a growing group of radicals who not just sought to reform Cameroon into a federalist state, but to completely break away to form a new country.[17]

Increasing pressure for autonomy or independence reduced trust and engagement between the government and the Anglophone minority, with the result that by 2017 there was only one Anglophone among 36 ministers with portfolio in the Cameroonian government.[15]

Protests and civil war in Cameroon

[edit]In November 2016, a number of large protests and strikes were organized, initially by Anglophone lawyers, students, and teachers focused on the growing marginalization of English and Anglophone institutions in the law and education.[29] Several demonstrations were violently dispersed by security forces, leading to clashes between demonstrators and police in which several people were killed. Violence by both sides undermined negotiations in early 2017, which fell apart without an agreement.[30] The violence led to additional demonstrations, general strikes (called "lockdowns"), and further crackdowns by the government into early 2017, including the banning of civil society organizations, cutting off phone and internet connections from January to April,[31] and arrests of demonstrators.[32] Although the government established a commission to focus on Anglophone grievances and took steps to address issues of language equity in courts and schools, continued distrust and harsh responses to protests prevented significant deescalation. Meanwhile, radicals set up propaganda channels such as the "Ambazonian Broadcasting Co-operation" which spread their beliefs among Anglophones.[17]

By late 2017, with dialogue efforts moribund and violence continuing on both sides, the leading Ambazonian nationalist movements organized the umbrella organization Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front (SCACUF). SCACUF unilaterally declared the region's independence as Ambazonia on October 1, the anniversary of Southern Cameroons' independence from the United Kingdom. SCACUF sought to transition itself into an interim government with its leader, Sisiku Ayuk Tabe Julius, as interim president.[33] At least 17 people were killed in protests following the declaration of independence, while fourteen Cameroonian troops were killed in attacks claimed by the Ambazonia Defence Forces.[34] The Cameroonian government stated that the declaration had no legal weight[35] and on November 30, 2017, the President of Cameroon signaled a harder line on separatist attacks on police and soldiers.[36] A massive military deployment accompanied by curfews and forced evacuations of entire villages.[37] This temporarily ended hopes for continued dialogue and kicked of full-fledged guerilla war in Southern Cameroons. Several different armed factions have emerged such as the Red Dragons, Tigers, ARA, Seven Kata, ABL, with varying levels of coordination with and loyalty to Ambazonian political leaders.[38] In practice, pro-independence militias operate largely autonomously from political leaders, who are mostly in exile.[39]

Discourse on root causes

[edit]Researcher Rogers Orock argued that the immediate cause of the Anglophone Crisis was the Cameroonian government's violent suppression of the peaceful 2016–2017 Cameroonian protests.[40] This view was mirrored by Felix Agbor Nkongho, a human rights lawyer and member of the outlawed Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSC). Agbor Nkongho maintained that the protests were initially peaceful and only intended to "draw attention to the international community to what we were going through as a people".[41]

In turn, the protests were rooted in the growing marginalisation of Anglophones within Cameroon. Despite being officially bilingual, the Cameroonian administration and public life have traditionally favored those speaking French, resulting in a growing sense among Anglophones that they were being reduced to a "second-class citizenship" and existing in a "coloniality".[40] For instance, human rights advocate Kah Walla pointed out that the entrance exam of Caneroon's École Nationale d’Administration et de Magistrature was only in French until 2017, with most Anglophone applicants being eliminated.[42] The belief in marginalization developed over the course of several decades, causing sporadic protests and opposition which were suppressed by Ahmadou Ahidjo's and Paul Biya's governments. This only strengthened the resentment, as many Anglophones also regarded the Cameroonian administration as authoritarian and corrupt.[40][17] Researcher Alex Purcell also argued that the radical Ambazonian movement was rooted in the long-time dissatisfaction of Anglophones due to insufficient public service, corruption, a lack of development, electoral irregularities, inept governance, austerity, and high unemployment.[17]

The widespread belief in marginalisation of Anglophones is expressed through particular phrases used by Ambazonian separatists: For instance, separatists have used the derogatory terms "banana republic" or "colonial Cameroun" to describe the French-speaking parts of Cameroon. "Banana republic" is used as a criticism of the Cameroonian institutions, whereas "colonial Cameroun" is used to criticize the Francophone dominance.[43]

After the civil war began, moderate Anglophone activists lost influence, furthering the radicalization of the separatists.[41][42] One activist, Balla Nkongho, pointed out that the Cameroonian government's decision to outlaw local Anglophone civil groups, arrest activists, and cut off the internet in the affected regions in 2017 allowed radical exiles to rise in prominence. The latter then took control of the opposition movement and spread separatist propaganda from abroad; this propaganda sometimes became the "only information the people had access to" in Anglophone areas.[42] Social media became dominated by separatists. For instance, the "Ambazonian Broadcasting Co-operation" spread much propaganda and misinformation in 2017, greatly contributing to the growing anger of Anglophones.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Fanso, Verkijika (1990). Trade and Supremacy on the Cameroon Coast, 1879–1887. Palgrave MacMillan.

- ^ Victoria, Centenary Committee (1958). Victoria – Southern Cameroons 1858–1958. London: Spottiswoode Ballantyne.

- ^ "Simon-Milner Declaration". Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "British Mandate for the Cameroons". The American Journal of International Law. 17 (3). JSTOR: 138–141. 1923. doi:10.2307/2212948. JSTOR 2212948.

- ^ Kingdom, United (June 16, 1948). Report on the Administration of Cameroons under United Kingdom Trusteeship 1947. New York: United Nations. p. 14.

- ^ Njingti Budi, Reymond (June 2019). "Colonial Administrative Integration of African Territories: Identity and Resistance in Nigeria's Southern Cameroons, 1922–1961". IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities. 6 (1): 109–122. doi:10.22492/ijah.6.1.09. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Mbile, N.N. (2011). Cameroon Political Story: Memories of an Authentic Eye Witness. Bamenda: Langaa. pp. 85–88.

- ^ a b "United Nations Trusteeship Council. 1961. Report of the United Nations Commissioner for the Supervision of the Plebiscites in the Southern and Northern Parts of the Trust Territory of the Cameroons Under United Kingdom Administration" (PDF). Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Konings, Piet; Nyamnjoh, Francis Beng (1 January 2003). Negotiating an Anglophone Identity: A Study of the Politics of Recognition and Representation in Cameroon. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-13295-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lynn, M., ed. (2001). "The future of the Southern Cameroons': co brief for Mr Macleod. British Documents on the End of Empire Project". British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming. 7.

- ^ Lunn, J.; Brooke-Holland, L. "The Anglophone Cameroon Crisis. Briefing House of Commons Library" (PDF). Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Lynn, M., ed. (2001). "Lennox-Boyd. 1959. CO 554/1659 31 Jan 1959. [Cameroons]: minutes from Mr Lennox-Boyd to Mr Macmillan. Outlining Possible Courses of Action for the Future of the Cameroons". British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming. 7.

- ^ a b "Report for the US Department of Justice: Pressure Groups in Southern Cameroons" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress. November 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "1608 (XV) The future of the Trust Territory of the Cameroons under United Kingdom administration. 994th Plenary meeting. 21 April 1961. Addendum document A/4727" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Cameroon's Anglophone Crisis at the Crossroads". International Crisis Group. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "African Areas to Unite". 20 July 1960. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alex Purcell (28 November 2023). "Amba Boys: Transforming Pacifists into Warmongers?". Grey Dynamics. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Hure, Francis. "memo of 12th April 1966 of the french ambassador in Cameroon to the french foreign minister". Mendafilms. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ Elections in Cameroon Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine African Elections Database

- ^ Roger, Jules, and Sombaye Eyango. Inside the Virtual Ambazonia: Separatism, Hate Speech, Disinformation and Diaspora in the Cameroonian Anglophone Crisis, p. 28 (2018).

- ^ Takougang, J.; Amin, J. A. (2018). Post-Colonial Cameroon: Politics, Economics, and Society. New York: Lexington Books. pp. 78–80.

- ^ "Flag of Cameroon". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- ^ Takougang, Joseph (2019-01-25), "Nationalism and Decolonization in Cameroon", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.619, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4

- ^ "Cameroon : History | The Commonwealth". thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- ^ "Gorji-Dinka v. Cameroon, Comm. 1134/2002, U.N. Doc. A/60/40, Vol. II, at 194 (HRC 2005)". www.worldcourts.com. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- ^ Jumbam, M. "The All Anglophone Conference (April 2–3, 1993)". Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ "Nations & Peoples". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ "News 28th of March 2018". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ "Cameroon teachers, lawyers strike in battle for English". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- ^ "Cameroon's Anglophone Crisis at the Crossroads". International Crisis Group. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Caldwell, Mark (21 April 2017). "Cameroon restores internet to English-speaking region". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "A Turn for the Worse: Violence and Human Rights Violations in Anglophone Cameroon". amnesty.org. Amnesty International. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Southern Cameroons gets new government with Sessekou Ayuk Tabe as Interim President". Cameroon Concord. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Cameroon government 'declares war' on secessionist rebels". 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Cameroon's English-speakers call for independence". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Biya declares war on Anglophone separatists – The SUN Newspaper, Cameroon". The SUN Newspaper, Cameroon. 2017-12-05. Archived from the original on 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ^ "Cameroon escalates military crackdown on Anglophone separatists". Reuters. 6 December 2017.

- ^ Cameroon's Anglophone crisis: Red Dragons and Tigers – the rebels fighting for independence, BBC, Oct 4, 2018. Accessed Oct 4, 2018.

- ^ Frohlich, Silja; Kopp, Dirke (2019-09-30). "Who are Cameroon's self-named Ambazonia secessionists?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rogers Orock (11 August 2022). "Cameroon: how language plunged a country into deadly conflict with no end in sight". The Conversation. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b Mimi Mefo Takambou (10 January 2021). "Anglophone Cameroon: From crisis to chaos". DW. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Nancy-Wangue Moussissa (2 August 2022). "Cameroon: Crisis grinds on due to anglophone divisions, Yaoundé's unwillingness to negotiate". The Africa Report. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Nkwain 2022, p. 245.

Works cited

[edit]- Nkwain, Joseph (July 2022). "Current Insights into the Evolution of Cameroon English: The Contribution of the 'Anglophone Problem'" (PDF). Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts. 9 (3). Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research (ATINER): 233–260. doi:10.30958/ajha.9-3-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Akoh, Harry A., ed. (2024). In Search of an Independent Ambazonian Nation: Dimensions of Identity and Freedom. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3031457760.

- Anyangwe, Carlson (2024). African-on-African Colonization: The Ill-Fated Ambazonia-Cameroun Political Partnership. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-66695-063-2.

- Jacob, Patience Kondu; Lenshie, Nsemba Edward; Okonkwo, Ifeoma Mary-Marvella; Ezeibe, Christian; Onuoha, Jonah (February 2022). "Ambazonian Separatist Movement in Cameroon and the Dialectics of Cameroonian Refugee Crisis in Nigeria". Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 22 (2). Taylor & Francis: 386–401. doi:10.1080/15562948.2022.2037807.