Olive Wharry

Olive Wharry | |

|---|---|

Wharry after a 32-day hunger strike in 1913 | |

| Born | 29 September 1886 London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Died | 2 October 1947 (aged 61) Torquay, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Artist and suffragette |

Olive Wharry (29 September 1886 – 2 October 1947) was an English artist, arsonist and suffragette, who in 1913 was imprisoned with Lilian Lenton for burning down the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens.[1]

Early life

[edit]Olive Wharry was born into a middle-class family in London, the daughter of Clara (1855-1910, née Vickers) and Robert Wharry (1853-1935), a doctor;[2] she was the only child of her father's first marriage. Wharry had three much younger half-brothers and a half-sister from his second marriage. She grew up in London, then the family moved to Devon when her father retired from medicine. On leaving school Wharry became an art student at the School of Art in Exeter, and in 1906 she travelled around the world with her father and mother. Her first arrest was for window smashing in July 1909. She became active in the Women's Social and Political Union and was also a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage.

1911 to 1913

[edit]In November 1911 Wharry was arrested for taking part in a WSPU window-smashing campaign, and, after being released on bail guaranteed by Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Mrs Saul Solomon, was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. During this sentence and the others that followed she kept a scrapbook which includes the autographs of fellow Suffragettes.[3] This scrapbook was an exhibit in the British Library's Taking Liberties exhibition (2008–09).[4]

In March 1912 Wharry was arrested again after more window-smashing and was sentenced to six months' imprisonment in Winson Green Prison in Birmingham. She took part in a hunger strike and was released in July 1912, before completing her sentence. In November 1912 she was reported as being arrested as "Joyce Locke" with other suffragettes, Fanny Parker and Marion Pollock in Aberdeen Music Hall, found hiding there before the Chancellor of the Exchequer was due to speak, carrying 'explosive' toy guns, and involved in a scuffle during Lloyd George's meeting.[5] She was sentenced to five days in prison, but during that time she managed to smash her cell windows.[6][4]

Kew Gardens arson

[edit]

On 7 March 1913, aged 27, she and Lilian Lenton were sent to Holloway Prison for setting fire to the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens, causing £900 worth of damage. The pavilion's owners had only insured it for £500. During her trial at the Old Bailey Wharry was again charged under the assumed name "Joyce Locke" and regarded the proceedings as a "good joke". She stated that she and Lenton had checked that the tea pavilion was empty before setting fire to it. She added that she had believed that the pavilion belonged to the Crown, and that she wished for the two women who actually owned it to understand that she was fighting a war, and that in a war even non-combatants had to suffer. When Wharry was sentenced to eighteen months with costs, refusing to pay she cried out "I will refuse to do so. You can send me to prison, but I will never pay the costs".[7]

In prison Wharry went on hunger strike for 32 days, passing her food to other prisoners, apparently unnoticed by the warders.[1][8] Wharry said that during her time in prison her weight had plummeted from 7 st 11 lb to 5 st 9 lb (50 kg to 36 kg).

In May 1913, her father, Dr Richard Wharry, was prosecuted for assaulting the process server who came to Holsworthy to serve a writ for Olive Wharry to pay compensation for the fire damage at Kew.[9][10]

Other prison sentences

[edit]

Wharry was arrested and imprisoned eight times between 1910 and 1914 for her part in various WSPU window-smashing campaigns, sometimes under the name "Phyllis North", sometimes as "Joyce Locke". Each of her prison sentences were characterised by her going on hunger strike, being force-fed and then released under Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913, known as the Cat and Mouse Act.[1]

In May 1914 she was sentenced to a week in prison after taking part in a deputation to King George V. It was a matter of honour to Wharry not to complete any prison sentence, and, after again going on hunger strike, she was released after three days. In June 1914 she was arrested at Carnarvon after breaking windows at Criccieth during a meeting held by Lloyd George. Being held on remand, she again went on hunger strike and was released. As "Phyllis North" she was arrested in Liverpool and was brought back to Carnarvon where she received a prison sentence of three months.[6] Wharry was sent to Holloway Prison to complete this sentence, and where she was held, on hunger strike, in solitary confinement. Wharry was given a Hunger Strike Medal "for Valour" by the WSPU.[citation needed]

Home Office reports show that some of the doctors who treated her at Holloway thought she was insane, or found it convenient to do so rather than accept the political arguments which justified suffragette activism,[11] and her scrapbook, which documents her time in this prison and in various other prisons around the country, suggests otherwise. It is full of drawings of prison life, satirical poems, autographs of other suffragettes and a photograph of herself and Lilian Lenton in the dock during their trial for the arson attack on Kew Gardens of 1913.[3]

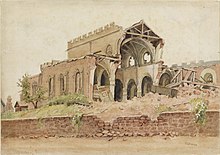

The pages in her scrapbook, held by the British Library in London, also record her weight loss on release from prison, and contains newspaper cuttings of a policeman carrying her bags on her release from prison and a burnt down tea pavilion at Kew Gardens.[3][4][12] Wharry was released into the care of Dr. Flora Murray on 10 August 1914 under the Government's amnesty of suffrage prisoners.

Death and legacy

[edit]

Later in life Wharry made her home at Dart Bank in Burridge Road in Torquay in Devon.[13] She made fellow Suffragette Constance Bryer (1870–1952) an executor of her 1946 will, in which she requested that her body be cremated and her ashes scattered on "the high open spaces of the Moor between Exeter and Whitstone". In her will she left Bryer an annuity of £200, her hunger strike medal and some of her etchings and books. The remainder of her fortune of £41,635 15s 8d she left to Margaret Harriett Wright, a widow, and Norman Wharry, a medical student. Both Wharry and Byer's hunger strike medals remain together in a private collection.[6]

Olive Wharry died at Heath Court Nursing Home in Torquay in 1947 at the age of 61. She never married, and never had children.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Wharry on 'The Postcodes Project'". Archived from the original on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ 1901 England Census for Olive Wharry - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- ^ a b c British Library Add. MS 49976

- ^ a b c Wharry's prison scrapbook on the British Library website

- ^ Pedersen, Sarah. "The Aberdeen Women's Suffrage Campaign". suffrageaberdeen.co.uk. copyright WildFireOne. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Elizabeth The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866–1928 Routledge (1999) (pg 707) Google Books

- ^ 'Girl Suffragette to Jail As Firebug; Takes Eighteen Months' Sentence for Kew Outrage as a Good Joke' The New York Times, 8 March 1913.

- ^ 'Mrs. Pankhurst Doing Well, Unfed; Like Olive Wharry, Who Is Released After 32 Days of Hunger Strike' The New York Times, 9 April 1913.

- ^ Miss Olive Wharry, Devon History Society online. Accessed 15 November 2022.

- ^ Portsmouth Evening News, 8 May 1913.

- ^ "The Suffragettes and Holloway prison". Museum of London. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Photograph of pages from Wharry's scrapbook – British Library website

- ^ a b England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966, 1973-1995 for Olive Wharry - Ancestry.com (subscription required)