Olduvai theory

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Olduvai Theory posits that industrial civilization, as it currently exists, will have a maximum duration of approximately one hundred years, beginning in 1930. According to this theory, from 2030 onward, humanity is expected to gradually regress to levels of civilization comparable to those experienced in the past, ultimately culminating in a hunting-based culture by around 3000 AD.[1] This regression is likened to the conditions present three million years ago when the Oldowan industry developed, hence the name of the theory.[2][note 1] Richard C. Duncan, the theory's proponent, formulated it based on his expertise in energy sources and his interest in archaeology.

Originally proposed in 1989 under the name "pulse-transient theory",[3] the concept was rebranded in 1996 to its current name, inspired by the renowned archaeological site of Olduvai Gorge, although the theory itself does not rely on data from that location.[1] Since the initial publication, Duncan has released multiple versions of the theory, each with varying parameters and predictions, which has generated significant criticism and controversy.

In 2007, Duncan defined five postulates based on the observation of data:

- The world energy production per capita.

- Earth carrying capacity.

- The return to the use of coal as a primary source and the peak oil production.

- Migratory movements.

- The stages of energy utilization in the United States.[2]

In 2009, he published an updated version that reiterated the postulate regarding world energy consumption per capita, expanding the comparison from solely the United States to include OECD countries, while placing less emphasis on the roles of emerging economies.[4]

Scholars such as Pedro A. Prieto have used the Olduvai Theory and other models of catastrophic collapse to formulate various scenarios with differing timelines and societal outcomes.[5][6] In contrast, figures like Richard Heinberg and Jared Diamond also acknowledge the possibility of social collapse but envision more optimistic scenarios wherein degrowth can occur alongside continued welfare.[7][8][6]

Criticism of the Olduvai Theory has focused on its framing of migratory movements and the ideological stance of its publisher, Social Contract Press, known for advocating anti-immigration measures and population control.[9][10] Various critiques challenge the theoretical foundations and assert that alternative perspectives, such as those of Cornucopians,[11] proponents of resource-based economies,[12] and environmentalist positions, do not support the claims made by the Olduvai Theory.

History

[edit]Richard C. Duncan is an author known for proposing the Olduvai theory in 1989, originally titled "The Pulse-Transient Theory of Industrial Civilization."[3] This theory was later expanded in 1993 with the publication of the article "The Life-Expectancy of Industrial Civilization: The Decline to Global Equilibrium"[13]

In June 1996, Duncan presented a paper titled "The Olduvai Theory: Falling Towards a Post-Industrial Stone Age Era", during which he adopted the term "Olduvai theory" to replace the earlier "pulse-transient theory".[1] An updated version of his theory, titled "The Peak of World Oil Production and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge", was presented at the Geological Society of America's 2000 Symposium Summit on November 13, 2000.[14] In 2005, Duncan further extended the data set of his theory to 2003 in the article "The Olduvai Theory: Energy, Population, and Industrial Civilization."[15]

Description

[edit]The Olduvai theory is a model that primarily draws from the peak oil theory and the per capita energy yield of oil. It posits that, in light of anticipated resource depletion, the rates of energy consumption and global population growth cannot mirror those of the 20th century.[2]

The theory is characterized by the concept of material quality of life (MQOL), which is defined by the ratio of energy production, use, and consumption (E) to the growth of the world population (P) (MQOL = E/P).[4] From 1954 to 1979, this ratio grew annually by approximately 2.8%. However, from 1979 to 2000, it exhibited erratic growth at only 0.2% per year.[16] Between 2000 and 2007, the rate experienced exponential growth, largely due to the rise of emerging economies.[4]

In earlier works, Richard C. Duncan identified 1979 as the peak year for per capita energy consumption and, consequently, the peak of civilization. However, he has since revised this assessment, considering 2010 to be the likely peak year for per capita energy consumption due to the growth observed in emerging economies.[4] Despite this adjustment, Duncan maintains that by 2030, per capita energy production will approximate levels seen in 1930, which he identifies as a potential endpoint for current civilization.[4]

The theory argues that the first reliable signs of collapse are likely to consist of a series of widespread blackouts in the developed world. With the lack of electrical power and fossil fuels, there will be a transition from today's civilization to a situation close to that of the pre-industrial era. He goes on to argue that in events following that collapse the technological level is expected to eventually move from Dark Ages-like levels to those observed in the Stone Age within approximately three thousand years.[2]

Duncan's formulation of the Olduvai theory is based on several key data points:[17]

- Data on global energy production per capita.

- Population trends from 1850 to 2005.

- Estimates of Earth's carrying capacity in the absence of oil.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

- Stages of energy utilization in the United States, which are expected to reflect global trends due to its dominant position.

- Estimation of the year 2007 as the time of the peak oil.

- Migratory movements or attractiveness principle.

Duncan articulates five primary postulates within the Olduvai theory:[24]

- The exponential growth of world energy production ended in 1970.

- The intervals of growth, stagnation, and final decline of energy production per capita in the United States anticipate the intervals of energy production per capita in the rest of the world. In such intervals, there is a shift from oil to coal as the primary energy source.

- The decline of industrial civilization is projected to begin around 2008-2012.

- Partial and total blackouts are considered reliable indicators of the terminal decline of industrial civilization.

- Global population is expected to decrease in tandem with the decline in per capita energy production.

Bases for the formulation of the theory

[edit]Carrying capacity limit and demographic explosion

[edit]The sustainable capacity of the Earth without oil, according to some estimates, is between 500 and 2,000 million people. This figure has been surpassed significantly, attributed to an economic structure reliant on inexpensive oil.[25][18] It is posited that the Earth's homeostatic balance is around 2 billion people. As oil resources diminish, it is suggested that over 4 billion people may be unable to sustain themselves, potentially leading to a high mortality rate.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Historically, prior to 1800, the global population doubled approximately every 500 to 1,000 years, with the world population nearing 1 billion by that time.[26] The onset of the Industrial Revolution and colonial expansion led to a shift in demographic growth rates, particularly in the Western world, where the population began to double in just over 100 years. By 1900, the global population reached approximately 1.55 billion.[26] The Second Industrial Revolution further accelerated population growth, with the global population doubling in less than 100 years. During the peak of oil extraction and the advent of the digital revolution, the global population grew from 2.4 billion in 1950 to about 6.07 billion by 2000, reflecting a doubling time of roughly 50 years.[26]

The theory posits that the Earth's capacity for sustaining human population has been exceeded since around 1925, predicting that the rate of population growth is unsustainable. It suggests an apocalyptic scenario in which global population growth would slow in 2012 due to an economic downturn, peaking in 2015 at approximately 6.9 billion people. Following this peak, the theory anticipates that births and deaths would equalize around 2017, resulting in a 1:1 ratio, after which deaths would surpass births (>1:1), leading to a significant decline in population. Projections indicate that the global population could decrease to about 6.8 billion by the end of 2020, 6.5 billion by 2025, 5.26 billion by 2027, and approximately 4.6 billion by 2030. Ultimately, it is suggested that the population may stabilize between 200 million and 500 million by 2050-2100.[15]

Duncan's forecasts are compared with those of Dennis Meadows in his book The Limits to Growth (1972).[15] While Duncan predicts a peak population of 6.9 billion in 2015, Meadows anticipates a peak of approximately 7.47 billion in 2027. Duncan also estimates a decline to 2 billion by 2050, in contrast to Meadows’ projection of 6.45 billion for the same year.[15]

Alternative estimates aligned with Olduvai's theory suggest that the population may peak between 2025 and 2030, reaching between 7.1 billion and 8 billion before declining symmetrically, resembling a Gaussian bell curve.[27]

Scholars such as Paul Chefurka emphasize that the Earth's carrying capacity will be influenced by various factors, including ecological damage incurred during industrialization,[18] the development of alternative technologies or substitutes for oil, and the preservation of knowledge and traditional lifestyles that could enable sustainable living for the remaining population.[5][18]

Principle of attractiveness

[edit]This theoretical framework, informed by Jay Forrester's work on the dynamics of complex social systems,[28] suggests that per capita natural resource availability and material standards of living are fundamentally linked to the per capita energy yield of oil. The framework posits that the attractiveness of a country to immigrants is largely determined by the disparity in material standards of living between nations. For example, in 2005, the material standard of living in the United States was approximately 57.7 barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) per capita, compared to 9.8 BOE per capita for the rest of the world, resulting in a consumption gap of 47.9 BOE per capita.[29][note 2] This significant difference in lifestyle and consumption patterns is seen as a driving factor for immigration.

According to this theory, new immigrants tend to adopt the consumerist lifestyle of their host country, which can lead to increased resource demand and strain on the system.[28] Duncan argues that as immigration increases, the disparities in material living standards between the host country and the global average will diminish through an equalizing process, potentially leading the host country to approach the world’s material standard of living.

This proposition has faced criticism in various regions. Critics contend that while Duncan implies a need for stricter immigration policies, he does not adequately address the role of consumerist lifestyles in wealthier nations as a primary factor contributing to resource depletion.[9]

-

Per capita energy consumption expressed in kilograms of oil equivalent (kgoe) per person in 2001 by country. In black the countries for which no data were collected, in light colors the countries with the lowest consumption, in bold colors the countries with the highest consumption; those tending to red are those that have shown an increase in consumption and those tending to green are those that have shown a decrease in consumption.[30]

-

World migration in 2016, in blue the attractive countries, in orange the countries from which there is migration to the attractive countries. In green color the countries that showed negligible migration movements, and in gray the countries for which no data were collected.[31]

Return to the use of coal as a primary source

[edit]

The theory proposes that due to the predominance of one nation the rest of the world will follow the same sequence in the implementation of a resource as a primary source. It thus comparatively analyzes a chronology of resource utilization as a primary source between United States and the rest of the world:[33]

- In the United States until 1886.

- In the rest of the world until 1900.

- In the United States from 1886 to 1951.

- In the rest of the world from 1900 to 1963.

- In the United States from 1951 to 1986.

- In the rest of the world from 1963 to 2005.

- In the United States since 1986.

- In the rest of the world from 2005.

According to Duncan, from 2000 to 2005 while world coal production increased by 4.8% per year, oil increased by just 1.6%.[33]

The return to coal as a primary source, another taboo fact due to its high level of pollution, has been muted in the media as has the carrying capacity of the Earth for obvious political reasons, Duncan says.[2]

Energy consumption of the population

[edit]

The transition from oil to coal as a primary energy source in the United States is seen as indicative of broader global changes in energy consumption and production.[34] Duncan identifies three stages in U.S. energy consumption that reflect trends in global consumption:[35]

Growth

[edit]- 1945-1970: During this period, the U.S. experienced an average growth of 1.4% per capita energy production per year.

- 1954-1979: A parallel world growth stage emerged, with an average growth of 2.8% per capita energy production annually.

Stagnation

[edit]- 1970-1998: The U.S. entered a stagnation phase characterized by an average decline of 0.6% per year in per capita energy production.

- 1979-2008: This global stagnation period saw only a modest average growth of 0.2% per capita energy production per year, with a slight uptick after 2000, primarily driven by the growth of emerging economies.

Final decline or decay

[edit]- 1998 onwards: The U.S. faced a final decline phase, with an average decline of 1.8% per year in per capita energy production from 1998 to 2005.

- 2008-2012 onwards: A potential stage of final global decline is anticipated, although the rapid development of emerging economies and extensive coal utilization in China may temporarily mitigate this decline until around 2012.

Theory updates

[edit]2009 update

[edit]Following criticism regarding discrepancies in per capita energy consumption trends, Duncan published an updated analysis in 2009. This work compared the energy consumption curves of OECD member countries (30 nations) with those of non-OECD countries (165 nations), which include Brazil, India, and China.[4]

In this updated paper, Duncan identified several key points regarding per capita energy consumption:[4]

- 1973: Peak per capita energy in the United States.[4]

- 2005: OECD countries reached a peak per capita energy consumption of approximately 4.75 tonnes of oil equivalent (toe).[4][36][37]

- 2008: After having increased from 2000 to 2007 the per capita consumption of non-OECD countries by 28%, the composite leading indicator of China, India, and Brazil declined sharply in 2008,[38] leading him to conclude that the average standard of living in non-OECD countries has already begun to fall.[4] However, a report from the OECD in February 2010 appeared to contradict this assertion.[39]

- 2010: Most likely date of peak energy per capita globally.[4]

Duncan's forecast projected significant declines in average per capita energy consumption by 2030: a 90% decrease for the United States, an 86% decrease for OECD countries, and a 60% decrease for non-OECD countries. He anticipated that by 2030, the average standard of living in OECD countries would converge with that of the non-OECD world, reaching an estimated 3.53 barrels of oil equivalent per capita.[4]

-

Update 2000. Forecast of per capita energy consumption. In blue is the growth stage, in green and yellow is the stagnation stage, and in red is the final decline stage.[14]

-

Update 2007. Forecast of per capita energy consumption. In blue is the growth stage, in green and yellow is the stagnation stage, and in red is the terminal decline stage.[2]

-

Update 2009. Forecast of per capita energy consumption. In blue is the growth stage, in green and yellow is the stagnation stage, and in red is the final decline stage.[4]

Societal scenarios according to the theory

[edit]Pedro A. Prieto, a notable Spanish-language expert on the subject, has proposed a scenario of potential societal collapse based on various aspects of energy consumption theory.[5]

Crisis of the Nation-State

[edit]Prieto suggests that wealthy nations may experience heightened insecurity, leading to a transformation of democratic societies into totalitarian and ultraconservative regimes, driven by public demands for external resources and increased security.[5] He posits the possibility of conflict over scarce resources escalating into a global conflict, likened to a potential World War III. without ruling out scenarios similar to the final solution or nuclear war.[5] This scenario might involve three major blocks of civilizations: Western, Orthodox and Sinic, and Islamic. The roles of Japan and India would be significant as they navigate their positions within this context.[41][42]

In the event of resource scarcity, surviving nations could face widespread famine in urban centers, prompting social unrest and looting. Governments might respond with martial law and restrictions on social freedoms and property rights in an attempt to control the situation.[5] Persistent shortages could lead to insufficient rationing measures, resulting in government officials and military personnel exploiting resources for personal gain—an indication of the state's weakening authority.[5]

In a severe economic crisis, the value of fiat money could dramatically decline, leading to scenarios where basic necessities, such as food, become disproportionately expensive.[5] Dominant minority groups and military factions might establish localized dictatorships within previously stable nations, while the marginalized populations could form disorganized and volatile groups, resulting in chaotic struggles for resources. The ensuing conflict could lead to widespread societal collapse, impacting both the ruling factions and the general populace.[5]

Survivor's profile

[edit]Estimates suggest that cities with populations exceeding twenty thousand inhabitants would be particularly unstable during a societal collapse. In such scenarios, groups with a hunter-gatherer lifestyle—such as those in the Amazon, Central African jungles, Southeast Asia, as well as the Bushmen and Aboriginal communities in Australia—are projected to have higher life expectancies. Following them in survivability are smaller, more homogeneous agricultural communities, consisting of 300 to 2,000 individuals. These groups would be ideally situated near uncontaminated water sources, located far from large urban centers and the ensuing chaos of starving populations and looting military forces.[5]

Ultimately, a landscape of small agricultural villages could emerge, competing for the limited arable land available. Only those villages with land that can sustainably support their populations would survive.

Other visions

[edit]Pedro A. Prieto posits that scenarios involving large-scale conflicts, such as World War III, may be less likely if societal collapse occurs rapidly, as suggested by Olduvai theory. In a rapid collapse,[5] the majority of urban populations might perish due to famine, whereas a gradual collapse could lead to warfare spreading into more secure regions, including both large cities and remote rural communities.[5]

The perspectives on potential outcomes of a post-industrial era vary widely, ranging from visions of rapid and catastrophic societal collapse to those envisioning a slow and more manageable decline. Some theorists even propose scenarios that allow for degrowth while maintaining welfare systems, illustrating a broad spectrum of interpretations regarding the future of human societies.[6]

Catastrophic collapse or die-off

[edit]The pessimistic viewpoint, largely influenced by the Olduvai theory and associated works, suggests an impending catastrophic collapse or die-off.[43] Proponents of this perspective, including David Price,[44] Reg Morrison,[45] and Jay Hanson,[46][47][48] often invoke determinism[45]—such as strong genetic and energetic determinism (as articulated by Leslie A. White's Basic Law of Evolution)[49]—to argue that a collapse leading to the disintegration of civilized life is inevitable, dismissing the potential for a peaceful decline.[6]

Smooth decline or "prosperous downhill path"

[edit]In contrast, advocates of slow and benevolent collapse scenarios propose alternatives that envision a more manageable decline. Notable among these ideas is the "prosperous way downhill" conceptualized by Elizabeth and Howard T. Odum,[50] which suggests a gradual transition rather than a sudden collapse. James Kunstler discusses the end of suburbanization and a potential return to rural living.[51] Additionally, Jared Diamond presents a vision in which societies can choose to adapt or fail,[7] while Richard Heinberg outlines a "gradual shutdown" option.[8][52]

In his book Shutdown: Options and Actions in a Post-Coal World,[8] Heinberg identifies four possible paths for nations in response to the depletion of coal and oil:

- "Last One and We're Out" or "Last One Standing": This scenario depicts fierce global competition for the remaining resources.

- "Gradual Shutdown": This path emphasizes global cooperation in reducing energy consumption, promoting conservation, and managing resources sustainably, including population reduction.

- "Denial": In this scenario, there is a reliance on hope for unforeseen solutions or serendipitous events to resolve the crises, aligning with concepts like the black swan theory.

- "Life-Saving Community": This approach advocates for local preparations aimed at sustaining communities in the event of a broader economic collapse.

The Renaissance of utopias

[edit]In contemporary discourse, a resurgence of utopian visions has emerged, viewing societal collapse as both a potential outcome and a deliberate objective.[6] Similar to the 19th century and the early industrial era, this revival of romanticism and utopian thought reflects a response to predictions of collapse stemming from the industrial age.[6] This renaissance stands in contrast to declining sociological theories, which struggle to offer adequate solutions in the face of complex societal changes.[6]

Joseph Tainter posits that a collapsing complex society becomes smaller, simpler, and less stratified, leading to reduced social differences.[53] Theodore Roszak suggests that this scenario aligns with the utopian ideals of environmentalism, advocating for reduction, democratization, and decentralization.[54]

Ernest Garcia notes that many proponents of these new utopian movements are scientists from diverse fields, including geology, computer science, biochemistry, and evolutionary genetics, rather than traditional social scientists.[6] Among the notable recent utopian movements are anarchoprimitivism,[55] deep ecology, and techno-utopias such as transhumanism. These movements illustrate a wide array of visions aimed at reimagining society in the context of impending collapse and environmental challenges.

Critiques and positions on the theory

[edit]Criticism of the basis of the argument

[edit]Criticism of the limit of carrying capacity and population explosion

[edit]

This forecast differs from the 2004 United Nations report, which estimated global population trends from 1800 to 2300. The worst-case scenario outlined in the report projected that the world population would peak at approximately 7.5 billion between 2035 and 2040, followed by a decline to 7 billion by 2065, 6 billion by 2090, and around 5.5 billion by 2100.[56]

A 2011 report from the United Nations Population Division indicated that the world's population officially reached 7 billion on October 31, 2011,[57] with an estimated 7.8 billion by 2019.[58] This contrasts with Richard C. Duncan's estimate, which suggested a global population of approximately 6.9 billion by 2015.[59] Recent trends indicate a decline in population growth, attributed more to cultural and social factors leading to decisions to have fewer children, rather than deaths from famine and disease as mentioned in Duncan's theory.[60][61] In response to these trends, China ended its one-child policy, and several countries have introduced incentives to encourage higher birth rates.[62][63]

Criticism of the principle of attractiveness

[edit]Critics of Duncan's theory have highlighted xenophobic and racist cultural biases, particularly concerning the principle of attractiveness. Pedro A. Prieto has criticized the notion of closing borders to immigrants while simultaneously allowing the importation of depleting resources that contribute to high consumption levels in the United States.[9] Nonetheless, Prieto acknowledges that fundamental concepts of the theory, such as peak oil, land carrying capacity, and a return to coal as a primary energy source, are feasible to some extent.[9]

Many of Duncan's works have been published by Social Contract Press, an American publishing house founded by John Tanton and directed by Wayne Lutton. The press advocates for birth control and reduced immigration, often addressing cultural and environmental issues from a right-wing perspective. It has faced controversy, particularly for publishing The Camp of the Saints by French author Jean Raspail, which has led to its designation as a "hate group" by the Southern Poverty Law Center due to the nature of some of its publications.[10]

Critics of the peak oil estimate

[edit]

Some critics argue that the peak oil theory may be overstated or even a hoax, as suggested by Lindsey Williams in 2006.[65][note 3] Various governments, social organizations, and private companies have proposed peak oil dates that vary significantly, ranging from two years before to forty years after Duncan's estimate, reflecting differing projections of production curves.[64]

The abiogenic origin theory of petroleum, which has been discussed since the 19th century, posits that natural petroleum is formed in deep geological formations, potentially dating back to the Earth's formation. Geophysicist Alexander Goncharov from the Carnegie Institution in Washington has supported this theory, having simulated mantle conditions in 2009 to create hydrocarbons from methane, including molecules such as ethane, propane, butane, molecular hydrogen, and graphite.[66][67] Goncharov contends that all previous peak oil estimates have been inaccurate, suggesting that reliance on peak oil predictions is unfounded and that oil companies could explore new abiotic deposits.[66][67]

Criticism of the return to coal

[edit]

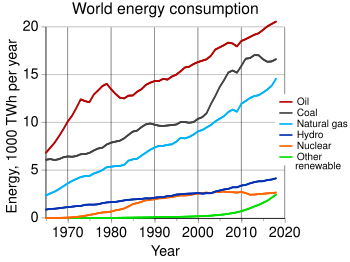

Additionally, data from various sources do not align with the prediction that coal would replace oil as the dominant energy source by 2005. According to the EDRO website, in 2006, oil accounted for 35.27% of global energy consumption, while coal represented 28.02%. Although coal usage was on the rise, oil remained a significant source.[68] Similarly, data from BP Global's energy graphs indicate that in 2007, oil consumption experienced a slight decrease from 3,939.4 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) to 3,927.9 Mtoe, while coal consumption increased from 3,194.5 Mtoe to 3,303.7 Mtoe during the same period.[69]

Critiques on per capita energy consumption

[edit]

Duncan's analysis asserts that the peak per capita energy consumption was 11.15 billion equivalent per capita per year (bep/c/yr) in 1979. However, data from the U.S. Department of Energy (EIA) indicates an increase to 12.12 bep/c/yr after 2004,[71][72] contradicting Duncan's claim that energy per capita did not grow exponentially from 1979 to 2008.

TheOilDrum.com suggests that a true peak in per capita energy consumption of approximately 12.50 bep/year occurred between 2004 and 2005, based on data from the United Nations, British Petroleum, and the International Energy Agency. Proponents of this view argue that Duncan primarily focused on per capita energy consumption of oil while overlooking the significant increases in coal consumption since 2000, driven by the demand in Asia, as well as the consistent growth of natural gas consumption since 1965.[70]

They contend that the peak of industrial civilization did not occur in 1979, but rather after 2004, with the duration of industrial civilization projected to extend from 1950 to 2044.[73] Additionally, they suggest that if other energy resources are less dependent on oil consumption trends, the overall duration of industrial civilization may exceed one hundred years.[74]

Following challenges to the notion that the rest of the world was mirroring U.S. trends in per capita energy consumption, Duncan published a new article in 2009 titled "Olduvai's Theory: Towards the Re-Equalization of the World Standard of Living." In this work, he compared global per capita consumption with that of the most developed countries (OECD).[4] He argued, based on a March 2009 OECD report, that world per capita energy consumption was beginning to decline. However, a subsequent OECD report in February 2010 indicated a significant recovery, contradicting Duncan's assertion.[39][38]

Political and ideological criticisms

[edit]Ecologist criticism

[edit]

Social ecologists and international organizations, such as Greenpeace, adopt a more optimistic outlook, focusing on alternative energy sources like geothermal, solar, and wind energy, which they view as low or non-polluting.[77] They express skepticism toward fusion energy, citing concerns about its potential pollution.[78] These groups argue that data on population growth often overlook the possibilities presented by social and technological advancements, including alternative energy solutions and radical lifestyle changes that could mitigate the negative impacts predicted by various theories. In contrast, market ecologists contend that necessary changes will emerge through market mechanisms, driven by the laws of supply and demand.[79]

Meanwhile, anarcho-primitivists and deep ecologists perceive the potential for civilizational collapse as an unavoidable trajectory of modern society.[55] They often frame this collapse as not only a likely outcome but also as a goal that may lead to a more sustainable existence, viewing it as a necessary response to the ecological and social crises facing civilization.[6][55]

Left-wing criticism

[edit]Some libertarians, anarchists, and socialists criticize peak oil and similar theories as exaggerations or fabrications that serve economic speculation. They argue that such theories promote the sale of more expensive and easily controllable resources that are either depleted or scarce, thereby sustaining the dynamics of the free market and benefiting the ruling classes.[80]

Jacque Fresco posits that while certain energy resources are deemed scarce, there are other abundant sources, such as geothermal energy, which could remain virtually inexhaustible for thousands of years at current consumption rates.[81] He asserts that these resources are less susceptible to control by social elites because they are not easily speculated upon. Fresco has also established The Venus Project, which aims to propose an alternative to the current capitalist economic model focused on monetary gain.[82][80]

In the past, there has been a movement online to scrutinize Jacques Fresco and his claims, suggesting possible fraud related to his initiatives.[83]

Authors like Peter Lindemann and Jeane Manning argue that numerous alternatives exist for freely obtaining and distributing energy.[84][85][86] They contend that implementing these alternatives could undermine the capitalist model of resource hoarding and distribution,[85] leading to conspiracy theories regarding the suppression of free energy technologies.[84] Prominent among these technologies is the wireless power transfer concept developed by Nikola Tesla.[84][85]

Proponents of these critiques often view the theories surrounding peak oil, warmongering, catastrophism, and neo-Malthusianism as part of an elitist agenda aimed at maintaining control over resources and populations.[80][note 4]

Right-wing criticism

[edit]Cornucopians, often associated with libertarians viewpoints, contend that concerns regarding population growth, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation—such as those articulated in peak oil theories—are exaggerated or misleading. They argue that market mechanisms would effectively address these issues if they were indeed real.[11][88][89]

The main theses advocated by cornucopians are generally optimistic and pragmatic, though critics sometimes label them as conservative, moralistic, and exclusionary. Key points include:

- Technological Progress Equals Environmental Progress: Cornucopians assert that environmental degradation is mitigated through technological advancements that enable cleaner and more efficient resource utilization.[11]

- Anti-environmentalism: They criticize catastrophist positions, such as Olduvai's theory, for being based on inadequate models that produce precarious scenarios that do not portray economic dynamics in their historical perspective. They reject the idea of degrowth because it goes against technological and, in turn, environmental progress.[11][90]

- Technological Optimism: They believe that technological innovation will continuously provide substitutes for depleting resources, allowing humanity to surpass ecological limits. Historically, this has been demonstrated as societies have transitioned between different technologies and energy sources. They also contend that advances in agricultural technology, including agrochemicals and genetic engineering, enhance land efficiency and food production.[11][91]

- Growth is green: Cornucopians maintain that economic growth is the solution to environmental problems, asserting that poverty—rather than wealth—leads to environmental degradation and misuse.[11]

- Reliance on the Free Market: They argue that new ownership models and markets will drive transitions to alternative technologies and energy sources through economic speculation.[11][79][91] Consequently, they oppose state intervention in these processes.[11][79]

- Abolition of birth control: Cornucopians view population growth as a net positive, asserting that each additional person contributes to technological advancement and societal progress.[11] This perspective stands in contrast to neo-Malthusian views that see population as a burden.[88][note 4]

- Anthropocentric Aesthetic Value: They defend natural resources based on their immediate utility and aesthetic value to humanity, rather than their long-term ecological sustainability.[11]

Criticism and national positions

[edit]

Conservatives, traditionalists, and nationalists viewpoints often prioritize immediate benefits from an ethnocentric or anthropocentric perspective, frequently overlooking potential adverse environmental impacts.[92][93][94][95][96][97] While they do not typically outright deny theories such as peak oil or Olduvai's theory, they may omit certain elements or the entirety of these theories, which can be seen as a form of institutional denial.[98] According to the theories, it is anticipated that many countries will shift from oil to coal or nuclear power, similar to the practices of the United States or China, without adequately considering the social or ecological consequences.[98][99][100]

One argument supporting this transition is the adoption of cleaner coal technologies, such as integrated gasification combined cycle,[101] which aims to reduce pollution while utilizing coal. However, the energy return from these methods may be lower compared to traditional, more polluting processes.

Additionally, the international collaboration on the ITER project among China, India, Japan, the United States, and Europe is presented as evidence of the scientific and technological feasibility of nuclear fusion.[102][103] While participation in the project has varied over time, proponents argue that successful fusion energy development could revolutionize energy production.

If fusion energy becomes viable, the energy potential from deuterium in the planet's water bodies is estimated to be equivalent to approximately 1,068 billion times the world’s oil reserves in 2009.[104][105][106][107][108] This suggests that each cubic meter of water could yield energy equivalent to 150 tonnes of oil.[108]

At the world consumption rate of 2007, this could theoretically sustain modern industrial civilization for about 17.5 billion years, assuming a constant population of 6.5 billion and no economic growth.[note 5] However, current economic systems rely on continuous growth, which complicates these projections.[109] For example, at a growth rate of 2% per year, oil consumption would double approximately every 34.65 years.[note 6] Under higher growth rates, such as 5% or 11.4%,[note 7][note 8] the available deuterium could be depleted in much shorter time frames—488 years and 214 years, respectively.

Some developed countries advocate a non-anthropogenic global warming or solar-origin version, perceiving environmental warnings as exaggerated.[110][111] Conversely, many developing nations view depletion theories and international environmental agreements as mechanisms imposed by developed countries to limit their progress and development.[110][90]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Until a few decades ago, special importance was given to the role of hunting in the subsistence of the first humans, and a hypothesis was put forward in which hominids were unspecialized hunters who took their prey to a base camp where they shared food. Revision of these ideas has been severe, especially since the 1968 international colloquium, Man the Hunter. Possibly Oldowan toolmakers were just foragers and scavengers.

- ^ The energy contained in a barrel of oil is equivalent to 1.46 x 106 Kcal or equivalent to one year of energy consumption of a forestry worker in the tropics (4,000 Kcal/day according to Apud and collaborators, 1999). However, for Matthew Savinar one barrel of oil is equivalent to 25,000 man-hours and for Roscoe Bartlett 12 workers working for a year.

- ^ Lindsey Williams is a Baptist church minister in Alaska who posits the conspiracy theory that peak oil is a form of enrichment directed by "social elites" through the methods of speculation and bankruptcy.

- ^ a b Malthus only advised honest celibacy as the only preventive means of overpopulation, declaring that he understood by moral constraint, that which a man imposes upon himself concerning marriage, from a motive of prudence, when his conduct, during this time, is strictly moral, and that his practical object was only to improve the lot of the lower classes of society. With time, however, the doctrine of Malthus divided among his disciples into two currents. A moderate current composed of those who attenuated his theses, such as J. B. Say, Hegewisch, Joseph de Maistre, Rossi, and Roscher, accepted in general the principle of Malthus under conscious procreation, but added that employing good economy and intelligent art, products can grow more rapidly than in arithmetical progression. On the other hand, a new current of disciples was formed, neo-Malthusianism, who went far beyond what Malthus proposed, and who, far from only advising reflection on honest celibacy, demanded a small number of children through measures ranging from contraception, and voluntary sterility to induced abortion.

- ^ On the planet there are 1.386×1018 m^3 of water. If each cubic meter of water is equivalent to 1030 boe in deuterium on earth there are 1.42×1021 boe in deuterium. That total between the annual consumption rate of 12.5 bep per capita in 6.5 billion inhabitants (1.42×1021bep/(12.5bep*6.5x109) gives us an approximate duration of 17.5 billion years.

- ^ At a growth rate of 2% per year we have that PET/(TP*2^(A/(In2*100/2))) = 1 where 200,700,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 tons of oil equivalent approximately in deuterium reserves in all bodies of water on the planet is PET, where 4,989,300. 477 tons of oil consumed approximately during the year 2011 is TP, where 1220.63 years are needed to equal TP and TEP is A, where 0.693 or natural logarithm of *2^ is In2, and where annual growth at 2% is 100/2. Equating or consuming TP to TEP the result of the equation is 1/1 = 1.

- ^ At a growth rate of 5% per year we have that PET/(TP*2^(A/(In2*100/5))) = 1 where 200,700,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 tons of oil equivalent approximately in deuterium reserves in all bodies of water on the planet is PET, where 4. 989,300,300,477 tons of oil consumed approximately during the year 2011 is TP, where 488.25 years are needed to equal TP and TEP is A, where 0.693 or natural logarithm of *2^ is In2 and where annual growth at 5% is 100/5. When equating or consuming TP to TEP the result of the equation is 1/1 = 1.

- ^ At a growth rate of 11.4% per year we have that TEP/(TP*2^(A/(In2*100/11.4))) = 1 where 200,700,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 tons of oil equivalent approximately in deuterium reserves in all water bodies on the planet is TEP, where 4,989,300. 477 tons of oil consumed approximately during the year 2011 is TP, where 214.14 years are needed to equal TP and TEP is A, where 0.693 or natural logarithm of *2^ is In2 and where annual growth at 11.4% is 100/11.4. Equating or consuming TP to TEP the result of the equation is 1/1 = 1.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Duncan (1996)

- ^ a b c d e f g Duncan (2007)

- ^ a b Duncan, R. C. (1989). Evolution, technology, and the natural environment: A unified theory of human history. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting, American Society of Engineering Educators: Science, Technology, & Society, 14B1-11 to 14B1-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Duncan (2009)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pietro, Pedro A. (8 September 2004). "El libro de la selva". Crisis energética (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i García (2006)

- ^ a b Diamond (2005)

- ^ a b c Heinberg (2005)

- ^ a b c d Pietro, Pedro A. (14 February 2007). "La teoría de Olduvai: El declive final es inminente". Crisis Energética (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b Southern Poverty Law Center (2001). "Anti-Immigration Groups". Southern Poverty Law Center, Intelligence Report. 101. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chang, Man Yu; Foladori, Guillermo; Pierri, Naína (2005). ¿Sustentabilidad?: Desacuerdos sobre el desarrollo sustentable (in Spanish). Miguel Ángel Porrua. p. 219. ISBN 9707016108.

According to the Cornucopians, in order to stop an activity potentially harmful to the physical environment or human health, irrefutable scientific evidence is necessary, which costs a lot of time and money and, for this reason, mere prevention may not justify the very high social cost perpetrated.

- ^ Fresco, Jacque. "Zeitgeits: The Movie - Transcript". Archived from the original on 2010-05-09. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

At present, we don't have to burn fossil fuels. We don't have to use anything that would contaminate the environment. There are many sources of energy available.

- ^ Duncan, R. C. (1993). The life-expectancy of industrial civilization: The decline to global equilibrium. Population and Environment, 14(4), 325-357.

- ^ a b Duncan, Richard C. (2000). "The Peak of World Oil Production and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge"

- ^ a b c d Duncan, R. C. (Winter 2005–2006). "The Olduvai Theory" (PDF). The Social Contract. 16 (2).

- ^ Duncan (2007, p. 147)

- ^ Duncan (2007, pp. 142–147)

- ^ a b c d e Chefurka, Paul (2007). "Population, The Elephant in the Room". Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

Industrial agriculture as practiced in the 20th and 21st centuries is supported by three legs: mechanization, pesticides/fertilizers and genetic engineering. Of those three legs, the first two are directly dependent on petroleum to run the machines and natural gas to act as the chemical feedstock...

- ^ a b Hayden, Howard C. (2004). "The Solar Fraud: Why Solar Energy Won't run the World". Pueblo West: Vales Lake Publishing.

The Earth's [living human] population has far exceeded the number that solar sources could sustain. Likewise, the agricultural technology that existed just a century ago could not possibly feed a population of billions. For those who long for the glorious old days of a population below one billion, it is useful to point out that the only way to this end is the death of many billions of those now alive, even if no children were born in the next thirty years.

- ^ a b McCluney, R. (2004). "The Fate of Humanity". Pueblo West: Vales Lake Publishing. Archived from the original on 2018-04-19. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

My warning for today: we are systematically ignoring the life support system of planet Earth. We have exceeded the carrying capacity of the planet by a factor of 3. For everyone to live as Americans do, it would take three Earths.

- ^ a b Grant, L. (2005). "The collapsing bubble: Growth and Fossil Energy". Santa Anna: Seven Locks Press.

The population of the less developed world has grown by two-thirds since 1950 and was poor in 1950. The need for a fundamental change in the ratio of resources to people in poor countries can, by itself, justify an optimal world population figure of one billion. Barring a catastrophe, it could take centuries to reach such figures, even with a determined global effort.

- ^ a b Pfeiffer, Dale Allen (2006). "Eating Fossil Fuels: Oil, Food and the Coming Crisis in Agriculture". New Society Publishers. ISBN 0865715653. Archived from the original on 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

Some studies suggest that without fossil fuel-based agriculture, the U.S. would only be able to support about two-thirds of its current population. For the planet as a whole, the sustainable figure is thought to be around two billion.

- ^ a b Thompson, P. (2006). "The Twilight of the Modern World: The Four Stages of the Post-oil Breakdown". Archived from the original on 5 February 2010.

Sooner or later, all remnants of our society will have vanished, turned into ruins to rival those of the Aztecs and Mayans. By then, all those who have been unable to convert to a sustainable, self-sufficient way of life may have perished, leaving only those living in independent communities to carry on the human story. The human population could fall to as few as one billion, scattered in farmland oases among deserts of buildings, rusting vehicles, and jungles.

- ^ Duncan (2007, pp. 141–142)

- ^ Duncan (2007, p. 142)

- ^ a b c US Census Bureau. "Historical Estimates of World Population". Archived from the original on 2 January 2011.

- ^ SIU Edwardsville, The End of World Population Growth Archived 2010-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Forrester, J.W. (1975). Collected Papers of Jay W. Forrester. Cambridge: Wright Allen Press. pp. 275–276.

The attractiveness principle states that, for any given class of population, all geographic areas tend to be equally attractive. Or perhaps more realistically put, all areas tend to become equally unattractive. Why do all areas tend toward equal attractiveness? I use the word "attractiveness" to qualify any aspect of a city that contributes to its desirability or undesirability. Population movement is an equalizing process. As people move to a more attractive area, they drive up prices and overburden employment opportunities, environmental capacity, available housing and public services. In other words, the growing population reduces all the characteristics of an area that was initially attractive.

- ^ Duncan (2007, p. 144)

- ^ International Energy Agency (IEA) Statistics Division (2006), Data Tables Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, World Resources Institute, Earth Trends.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. "The World FactBook". Archived from the original on 2008-08-12. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ "Coal consumption by region". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 2022-06-03. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- ^ a b Duncan (2007, p. 145)

- ^ Duncan (2007, p. 146)

- ^ Duncan (2007, pp. 146–147)

- ^ OECD (2009, p. 313)

- ^ OECD (2008)

- ^ a b OECD (2009)

- ^ a b OECD (2010). "OECD Composite Leading Indicators News Release" (PDF). Paris. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-06-03. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b Bożyk, Paweł (2006). "Newly Industrialized Countries". Globalization and the Transformation of Foreign Economic Policy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 0-75-464638-6.

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, United States: Simon & Schuster. p. 185. ISBN 0-684-81164-2.

- ^ Freytas, Manuel (2009-05-18). "Sepa porqué usted está parado sobre la tercera guerra mundial". IAR Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ DieOff.org The language of ecology defines "overshoot", "crash" and "die-off" Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Price, David (1995). "Energy and Human Evolution". Population and Environment: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 16 (4): 301–319. Bibcode:1995PopEn..16..301P. doi:10.1007/BF02208116.

- ^ a b Morrison, Reg (1999). The spirit in the gene: humanity's proud illusion and the laws of nature. Ithaca London: Comstock Pub. Associates, a division of Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3651-2.

- ^ Crisisenergetica.org (2005). "Articles translated from the Die Off website, created and maintained by Jay Hanson". Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Hanson, J. (2001). Synopsis Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hanson, J. (2001). Maximum power Archived 2021-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Decrease.com (2007). "White's Law". Archived from the original on 18 November 2011.

Leslie A. White formulates the "Basic Law of Evolution" in which he emphasizes the levels of energy use as determinants of cultural evolution. [...] As long as other factors are held constant, culture evolves as the amount of energy available per head per year grows, or as the efficiency of the means of making that energy work grows.

- ^ Odum, H.T. and E.C. Odum (2001). A prosperous way down: Principles and policies. Boulder, University Press of Colorado.

- ^ Kunstler, James Howard (2005). The Long Emergency. New York, United States: Grove Atlantic. ISBN 9781555846701.

- ^ Heinberg, Richard. China or the United States: which nation will maintain leadership? Archived 2011-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tainter, J. (1995). The collapse of complex societies. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Roszak, T. (1993). The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology. London, Bantam.

- ^ a b c Kimble, T.; Zerzan, J.; Jensen, J.; Yu Koyo Peya, Open Source Movies.[self-published source?]

- ^ a b United Nations (2004). "World population to 2300" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-15. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Lostiempos.com (2011). "World population reaches 7 billion". Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights (PDF). New York: United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-12. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Duncan (2007)

- ^ BBC News Mundo (2020). "6 países donde se reducirá drásticamente la población y uno donde crecerá (y qué consecuencias traerán estos cambios)". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2022-06-09. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Jiménez, Javier (2020). "El mundo vacío: cada vez hay más expertos convencidos de que el crecimiento de la población mundial está a punto de hundirse". Xataka (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2021-06-23. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Wilt, Chloe (2019). "The Government Will Pay You to Have Babies in These Countries". Money.com. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ BBC News Mundo (2015). "China anuncia el final de su política de hijo único". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2022-04-03. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b Hutter, Freddy. "TredLines.ca". Archived from the original on 2022-05-08. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ Lindsey Williams (2006) Peak Oil Hoax Archived 2021-08-31 at the Wayback Machine, Reformation.org.

- ^ a b Kolesnikov, Anton; Kutcherov, Vladimir G.; Goncharov, Alexander F. (2009). "Methane-derived hydrocarbons produced under upper-mantle conditions". Nature Geoscience. 2 (8): 566–570. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..566K. doi:10.1038/ngeo591. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b Fernández Muerza, Alex (2009). "Puede que haya mucho más petróleo del que se cree". Archived from the original on 2017-06-26. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b EDRO Seeding Socioeconomic Avalanches (16 November 2007). "Optimum-Energy Communities". Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ BP Global. "Energy charting tool". Archived from the original on 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b The Oil Drum (2006). "Revisiting the Olduvai Theory". Archived from the original on 2021-02-23. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

Coal production was on a carrousel [un]til the nineties when it started a sharp decline, then all of a sudden it sharply rebounded after 2000. This has most likely been due to the emerging economies of Asia.

- ^ "World Consumption of Primary Energy by Energy Type and Selected Country Groups, 1980-2004". U.S. Department of Energy. 2006. Archived from the original (XLS) on 15 May 2009.

- ^ Silverman, Dennis; Energy Units and Conversions Archived 2007-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, UC Irvine.

- ^ The Oil Drum (2006). "Revisiting the Olduvai Theory". Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

So we can assume that 2005 is very likely to be a peak year in Energy/Capita. 30% of 12,522 is approximately 3,756, a value first reached in 1950. In the scenario of an oil-driven world, this value is crossed again in 2044.

- ^ The Oil Drum (2006). "Revisiting the Olduvai Theory". Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

If it turns out that Oil drives the production of energy from other sources, the life expectancy of the Electric Civilization is less than one hundred years: i.e., X < 100. In case Oil does not drive the production of other energy sources, the life expectancy of the Electric Civilization is greater than or equal to one hundred years: i.e., X >= 100. In such a case, X will be limited by an upper bound not yet evaluated, set by the decline of finite energy sources other than Oil: i.e., X < U.

- ^ British Petroleum (2008). Statistical Review of World Energy 2008.

- ^ Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (2009), Renewables Global Status Report 2009 Update (PDF).

- ^ García Ortega, José Luis; Cantero, Alicia (2005). Renovables 2050. Un informe sobre el potencial de las energías renovables en la España peninsular (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

It would be technically feasible to supply 100% of the total energy demand with renewable sources. The most appropriate combination of technologies and their geographical location will depend on the energy distribution system, the need for generation regulation (linked to demand management), and the cost evolution of each technology.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Colunga, Alfredo. "La energía de fusión: posibilidades, realidades, partidarios y detractores". Archived from the original on 2008-06-24.

Most of the detractors of fusion energy, environmental groups such as Greenpeace or Ecologistas en Acción, focus their criticism on the fact that it is not a 100% clean form of energy, i.e. it generates highly polluting radioactive waste such as tritium. Tritium is a radioactive isotope that emits beta i radiation and can cause congenital diseases, cancer, or genetic damage if ingested. A hypothetical leak of these materials could, for example, contaminate water, turning it into tritiated water, also radioactive.

- ^ a b c Hahnel, R. (2005). Economic Justice And Democracy: From Competition To Cooperation. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93345-5. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ a b c Fresco, Jacque. "Zeitgeits: Addendum - Transcript". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

The fact is, efficiency, sustainability and abundance are enemies of profit. To put it into a word, it is the mechanism of SCARCITY that increases profits..... What is scarcity? Based on keeping products valuable. Slowing up production on OIL raises the price. Maintaining scarcity of diamonds, keeps the price high. They burn diamonds at the Kimberly diamond mines- they are made of carbon-it keeps the price up.

- ^ Fresco, Jacque. "Zeitgeits: Addendum - Transcription". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

That said, it turns out that there is another form of clean, renewable energy that beats them all: geothermal energy. Geothermal energy uses what is called heat extraction, which, while a simple process using water, is capable of generating massive amounts of clean energy. In 2006, an MIT report on geothermal energy found that there are currently 13,000 zettajoules of energy available in the earth, with the possibility of 2000 zj being easily harnessed with improved technology. The total energy consumption of all countries on the planet is about half of one zettajoule per year. This means that about 4000 years of planetary energy could be harnessed in this medium alone. And if we understand that the Earth's heat generation is constantly renewing itself, this energy is truly unlimited and could be used forever.

- ^ Fresco, Jacque. "Zeitgeits: The Movie - Transcript". Archived from the original on 2010-05-09. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

Today, we don't have to burn fossil fuels. We don't have to use anything that pollutes the environment. There are many sources of energy available.

- ^ "Proyecto Venus contrastado" (in Spanish). 14 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

Currently, Fresco calls himself things like "social engineer" (it is not a degree, it is a qualification that he gives himself), "futuristic designer", "architectural designer" (avoiding calling you "architect", eh, Jacque?), "conceptual artist", "educator" and he also calls himself the closest thing to a degree that he has been able to find without being denounced by any professional association: "industrial designer". And I say "without being denounced" because Fresco has had, as the swindler that he is, numerous problems with various professional associations of all kinds, since he has tried to pass himself off on many occasions as what he is not, and has been forced to use increasingly "neutral" and "aseptic" terms when referring to his "training" or "profession".

- ^ a b c The Free Energy Secrets of Cold Electricity. Clear Tech. 2001. p. 130. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ a b c Lindemann, Peter (2001). "Where is the free energy?". Archived from the original on 2010-03-25. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ The Coming Energy Revolution: The Search for Free Energy. U.S.A.: Avery. 1996. p. 230. ISBN 0895297132. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ Wallace, Ed (2008); "Oil Prices Are All Speculation", Business Week.

- ^ a b Miller (1990). "Cornucopians versus Neomaltusians" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Rodríguez, José Carlos (December 2004). "Abundancia sin límites - La Ilustración Liberal". Spanish and American Magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b Mascaró Rotger, Antonio (2005). "El ecologismo falso y cruel, desenmascarado". La Ilustración Liberal (in Spanish) (26). Archived from the original on 21 December 2009.

- ^ a b Yergin, Daniel (2011). "There will be oil, Business and Finance". Expansion.com. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Routley, R. and V. (1980). 'Human Chauvinism and Environmental Ethics' in Environmental Philosophy (eds) D.S. Mannison, M. McRobbie and R. Routley. Canberra: ANU Research School of Social Sciences: 96-189.

- ^ Fabelo Corzo, José Ramón (1999). "¿Qué tipo de antropocentrismo ha de ser erradicado?" Archived 2021-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. In: Cuba Verde. In search of a model for sustainability in the 21st century. (in Spanish) Havana: José Martí. pp. 264-268.

- ^ Ryder, Richard (2005-08-05). "All beings that feel pain deserve human rights". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the mastery of nature. London: Routledge.

- ^ Plumwood, V. (1996). Androcentrism and anthrocentrism: Parallelism and Politics. Ethics and the Environment 1.

- ^ Naess, A. (1973). The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement. Inquiry 16: pp. 95-100.

- ^ a b Leggett, Jeremy K. (2005). Half gone: oil, gas, hot air and the global energy crisis. Portobello. ISBN 1846270049. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

It reminds me of those years when nobody wanted to listen to scientists talking about global warming. At that time we predicted events with a lot of attachment to the way they happened. Then as now, we wondered what it would take to get people to listen. It's not a conspiracy: it's institutional denial.

- ^ Alandete, David (2010). "Obama apoya con un crédito de 6.000 millones la construcción de la primera central nuclear en 30 años". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

It has been assumed that environmentalists are opposed to nuclear power, and nuclear power is the largest source of carbon-free fuel," the president says.

- ^ "China sustituye a Estados Unidos como principal consumidor mundial". Terra (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-08-28. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Ruiz de Elvira, Malen (2007). "El sueño del carbón limpio". ElPaís.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2007-05-21. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

The goal is to close the carbon cycle, to prevent CO2 emissions into the atmosphere, without radically changing the way it works. Hopes are pinned on perfecting and making CO2 capture processes cheaper

- ^ New Scientist Tech and AFP (2006). "Green light for nuclear fusion project". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Cox, Brian (2009). "How to build a star on Earth". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2022-01-16. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ 2.007x1020 tep de agua entre 1.879x1011 reservas de petróleo en toneladas Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) WolframAlpha.com

- ^ Genesis Group (2004). "Crude Oil Definitions". Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

So 1 barrel weighs: 158.9872972 * 0.88 = 139.908821536 kilograms

- ^ Convirtiendo cantidad de reservas de petróleo en barriles a toneladas Archived 2021-04-20 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish). WolframAlpha.com

- ^ Convirtiendo cantidad de agua terrestre de metros cúbicos a equivalente en tep Archived 2022-06-03 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish). WolframAlpha.com

- ^ a b Colino Martínez, Antonio (2004). Historia, Energía e Hidrógeno (PDF). Spain: Real Academia de Ingeniería. ISBN 8495662329. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2011.

- ^ Bartlett, Albert. "Aritmética, población y energía". Archived from the original on 2022-03-26. Retrieved 2022-06-03.[self-published source?]

- ^ a b Durkin, Martin. "The Great Global Warming Swindle". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2022-04-24. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Monbiot, George (2006-09-19). "The denial industry". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

Bibliography

[edit]- Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive. London: Allen Lane.

- Duncan, R.C. (1996). The Olduvai Theory:Sliding Towards a Post-Industrial Stone Age.

- Duncan, R. C. (Winter 2005–2006). "The Olduvai Theory Energy, Population, and Industrial Civilization" (PDF). The Social Contract. 16 (2): 1–12. ISSN 1055-145X.

- Duncan, R. C. (2007). "The Olduvai Theory: Terminal Decline Imminent" (PDF). The Social Contract. 17 (3): 141–151. ISSN 1055-145X.

- Duncan, R. C. (2009). "The Olduvai Theory: Toward Re-Equalizing the World Standard of Living" (PDF). The Social Contract. 19 (4): 67–80. ISSN 1055-145X.

- García, Ernest (2006). "El cambio social más allá de los límites al crecimiento: un nuevo referente para el realismo en la sociología ecológica" (PDF). Aposta: Revista de ciencias sociales (in Spanish). No. 27. ISSN 1696-7348. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-08. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- Heinberg, R. (2005). Powerdown: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0865715106.

- OECD (2009). OECD Factbook 2009: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics. OECD Publishing. p. 313. ISBN 978-9264056046.

- OECD (2008). OECD Factbook 2008: Estadísticas económicas, sociales y ambientales (in Spanish). OECD Publishing. ISBN 978-8497453905.

- Fernández Durán, Ramón (2011). La Quiebra del Capitalismo Global: 2020-2030 (in Spanish). Libros en Acción (Ecologistas en Acción). ISBN 978-84-936785-7-9.