Old Jaffa

Old Jaffa [yafa ha'atiká] – Ancient Yafo; Arabic: يافا العتيقة, Arabic pronunciation: [jaː.faː al.ʕa.tiː.qa] – Ancient Jaffa or يافا القديمة, Arabic pronunciation: [jaː.faː al.qa.diː.ma] – Old Jaffa) is a neighborhood of Israel and the oldest part of Jaffa. A neighborhood with art galleries, restaurants, theaters, museums, and nightclubs, it is one of Israel's main tourist attractions.

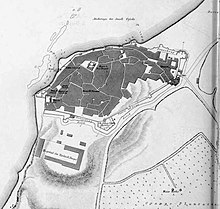

Old Jaffa is located in the northwest of Jaffa, on a hill along the Mediterranean Sea. Geologically, the hill of Old Jaffa is the continental north end of a kurkar ridge, historically further protected through fortifications and heightened by debris.

History

[edit]Ottoman Empire

[edit]The Old City was damaged by the Napoleonic wars and an earthquake in 1837.[1] When the wall of Jaffa, which was rebuilt in the early 19th century, was dismantled between 1878 and 1888 to allow expansion, both the city and the centres of government shifted eastwards, though the Old City remained the cultural center of the city.[2][3][4]

During the nineteenth century, the Christian population, especially the Greek Orthodox community, grew rapidly and dramatically in the Old Jaffa, and they formed the wealthy elite and the educated class in the city, and emerged as a major force in the increasingly middle-class trade of journalism.[5]

Mandatory Palestine

[edit]During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, links between Tel Aviv and the Jaffa Port were partially severed by the unrest in the Old City. Palestinian freedom fighters in Jaffa also used the Old City which contained a maze of homes, winding alleyways and an underground sewer system, to escape arrest by British security forces. Beginning in May 1936, in response to further Arab agitation in Jaffa, the British authorities suspended municipal services in the city, establishing barricades around the Old City and covering access roads with glass shards and nails. In June 15, the Royal Engineers used gelignite charges to demolish between 220 and 240 Palestinian Arab-owned homes in the Old City, leaving an open strip which cut through the center of Jaffa from end to end and displacing approximately 6,000 Palestinians.

The British authorities claimed that house demolitions in Jaffa were part of a "facelift" given to the Old City. Local Palestinian newspapers resorted to using sarcasm to describe the demolitions, writing that the British had "beautified" Jaffa using boxes of gelignite. Sir Michael McDonnell, then serving as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Palestine, found in favor of Arab petitions from Jaffa and, upholding existing laws regarding house demolitions, ruled against the demolitions carried out by British forces in the Old City. In response, the Colonial Office dismissed him from his post.[6] The revolt led to the British authorities to encourage the construction of the Tel Aviv Port on the Yarkon River estuary to the north of Tel Aviv to reduce reliance on the Jaffa Port.

Israel

[edit]Disputes about the merging of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, with the former wanting only to add the Jewish neighborhoods in the north of Jaffa and the latter wanting a total merge led to a gradual unification.[7] The Old City was partly added on 18 May 1949 as part of the first Arab-controlled land to fall under Jewish control.[7] The remainder of the Old City would be added in 24 April 1950 when the complete unification occurred.[7]

Old Jaffa has increasingly gentrified with the residential population dropping dramatically and an increasing number of art galleries, restaurants, souvenir shops as well as various ongoing archaeological digs.[8][1] According to Historian Menachem Klein, 70% of structures in old Jaffa have been destroyed between 1960 and 1985, with much of the old city being covered by Pisga Park.[9] There is a particular interest on the cultural melange by the relatively rare, in Israel, triple mix of Muslim, Jews, and Christian.[8]

Places in Jaffa

[edit]Pisgah Garden

[edit]The Pisgah garden, known also as the Abrasha garden was designed by Avraham Karavan. It is located on the top of Jaffa hill. The garden is connected to Kedumim Square and St. Peter's Church through the Zodiac Bridge over the road (Solomon's Bay Street) that borders the hill. The gardens integrate with their surroundings, so they can be reached from different directions. The area features several different actitives and not just a park, there are archaeological excavation areas, restored homes, works of art and cannons from the Napoleonic Wars.

Boundaries

[edit]

Current boundaries of the "Old Jaffa and Jaffa Port" neighborhood, as defined by the Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo (clockwise):

- North: north and east of Jaffa Beach, Retzif HaAliya HaShniya

- East: northbound lanes of David Raziel (putting the Jaffa Clock Tower in Old Jaffa), Yefet Street

- South: Yehuda HaYamit, Namal Yafo Street, the southern wall of the Jaffa Port parking lot

- West: the Mediterranean Sea shore

Attractions

[edit]- Subregions: Jaffa Port in the west and Yefet Street on its eastern border

- Museums, galleries and studios: Farkash Gallery, Uri Geller Museum, Ilana Goor Museum, watchmaker Itay Noy, Ilan Adar,[10]

- Places of worship: Al-Bahr Mosque, Libyan Synagogue, Mahmoudiya Mosque, Saint Nicholas Monastery, St. Peter's Church, St. George's Church, St. Anthony's Church (catholics), St. Anthony's Church (maronites)

- Theaters: The Arab-Hebrew Theater, Hasimta Theater, Nalaga'at

- Towers: Jaffa Clock Tower, Jaffa Light

Immediately outside Old Jaffa: Abouelafia Bakery, Abu Hassan Restaurant

References

[edit]- ^ a b Robert Barzelay (24 January 2017). "Exploring Jaffa: Israel's Ancient Port City". Culture Trip. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Kedar, B.Z. (1999). The Changing Land: Between the Jordan and the Sea: Aerial Photographs from 1917 to the Present. Wayne State University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8143-2915-3. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Pinsker, S.M. (2018). A Rich Brew: How Cafés Created Modern Jewish Culture. NYU Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-4798-2789-3. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ LeVine, M. (2005). Overthrowing Geography: Jaffa, Tel Aviv, and the Struggle for Palestine, 1880–1948. University of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-520-24371-2. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Robson, Laura (2011). Colonialism and Christianity in Mandate Palestine. University of Texas Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780292726536.

- ^ Hughes, M. (2009) The Banality of Brutality: British Armed Forces and the Repression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936–39, English Historical Review Vol. CXXIV No. 507, pp. 314–354.

- ^ a b c Arnon Golan (1995), The demarcation of Tel Aviv-Jaffa's municipal boundaries, Planning Perspectives, vol. 10, pp. 383–398.

- ^ a b Rebecca Amir (13 May 2018). "The art awakening transforming Jaffa". Israel21C. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Roth-Rowland, Natasha. “Wiping Palestinian History off the Map in Jaffa.” +972 Magazine, June 5, 2016. Link.

- ^ Abrams, Melanie (4 December 2017). "From light sculptures to silk-printing: Showcasing Israel's top artisans". Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 22 May 2019.