Obesity in the United Kingdom

This article needs to be updated. (February 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

Obesity in the United Kingdom is a significant contemporary health concern, with authorities stating that it is one of the leading preventable causes of death. In February 2016, former Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt described rising rates of childhood obesity as a "national emergency".[1] The National Childhood Measurement Programme, which measures obesity prevalence among school-age pupils in reception class and year 6, found obesity levels rocketed in both years groups by more than 4 percentage points between 2019–20 and 2020–21, the highest rise since the programme began. Among reception-aged children, those aged four and five, the rates of obesity rose from 9.9% in 2019–20 to 14.4% in 2020–21. By the time they are aged 10 or 11, more than a quarter are obese. In just 12 months, the rate is up from 21% in 2019–20 to 25.5% in 2020–21.[2]

Data from the Health Survey for England (HSE) conducted in 2018 indicated that 31% of adults in the England were recognised as clinically obese with a Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than 30.[3] 63% of adults were classified as overweight or obese (a body mass index of 25 or above), a 10 percent increase 1993.[3] More than two-thirds of men and 6 in 10 women were overweight or obese.[3] 28% of children aged between 2 and 15 years (inclusive) were overweight of them about 15% of children were obese.[3]

Rising levels of obesity are a major challenge to public health.[4] There are expected to be 11 million more obese adults in the UK by 2030, accruing up to 668,000 additional cases of diabetes mellitus, 461,000 cases of heart disease and stroke, 130,000 cases of cancer, with associated medical costs set to increase by £1.9–2.0B per year by 2030.[5] Adult obesity rates have almost quadrupled in the last 25 years.[6][7]

Combining three years of data (2012, 2013, and 2014) Public Health England identified Barnsley, South Yorkshire as the local authority with the highest incidence of adult obesity (BMI greater than 30) with 35.1%. Data from the same study revealed that Doncaster, South Yorkshire was the local authority with the highest overall excess weight with 74.8% of adults (16 years and over) with a BMI greater than 25.[8] In previous Public Health England studies based on 2012 data, Tamworth in Staffordshire had been identified as the fattest town in England with an obesity rate of 30.7%.[9]

Causes

[edit]Causes cited for the growing rates of obesity in the United Kingdom are multiple and the degree of influence of any one factor is often a source of debate. At an individual level, a combination of excessive food energy intake and a lack of physical activity is thought to explain most cases of obesity. Reduced levels of physical activity due to increased use of private cars, desk bound employment, a decline in home cooking skills and the ready availability of processed foods high in sugar, salt and saturated fats, are variously cited as contributing factors.[10][11]

Patterns of food consumption outside the home

[edit]

Media attention given to celebrity British chefs such as Gordon Ramsay, Heston Blumenthal, Marco Pierre White and many others with television shows and books encouraging home produced meals may have had a limited short-term impact on the growth of fast food chains such as McDonald's and Burger King.[citation needed][12] Other fast food outlets, high street bakeries,[13] and chain coffee shops offering hot drinks with sugar levels over three times the daily recommended limit[14] have nonetheless continued to rapidly expand. A 2015 University of Cambridge study reported that the total number of takeaway restaurants including fried chicken, fish and chips, pizza, kebab, Indian and Chinese takeaway shops has risen by 45% over the preceding 18 years.[15] Similarly, popcorn, although a healthy snack by itself, becomes a high calorie snack once topped with butter and various other flavourings offered by cinemas. For example, a large sweet popcorn at Cineworld has 1,180 calories.[16] Popularity for the microwavable snack has increased dramatically over the 5 years to 2016, with total sales increasing by 169%.[17]

Professor Jimmy Bell, an obesity specialist at Imperial College London, has stated that contrary to popular belief, the people of the United Kingdom have not become greedier or less active in recent years. One thing that has changed is the food that they eat, and, more specifically, the sheer amount of sugar they ingest. "We're being bombarded every day by the food industry to consume more and more food. It's a war between our bodies and the demands our body makes, and the accessibility that modern society gives us with food."[18]

Effects

[edit]Being overweight or obese increases the risk of illnesses, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, as well as some forms of cancer. In the United Kingdom, obesity and a BMI of 30 to 35 has been found to reduce life expectancy by an average of three years, while a BMI of over 40 reduced longevity by eight to 10 years.[19]

According to a report published by the Commons Health Select Committee in November 2015, treating obesity related medical conditions costs the National Health Service (NHS) £5 billion a year and has a wider cost to the economy of £27 billion.[20] A study published by two McKinsey researchers in the same year estimated costs to the United Kingdom economy of £6 billion ($9.6 billion) annually in direct medical costs of conditions related to being overweight or obese and a further £10 billion in costs on diabetes treatment. The cost of obesity and diabetes treatment in the NHS is equivalent to the United Kingdom's combined budget for the police and fire services, law courts, and prisons; 40 percent of total spending on education; and about 35 percent of the country's defense budget.[21][22]

British sperm quality has been negatively affected by obesity.[23][24]

Operational issues

[edit]Obese people often have to be moved by firefighters, as they are beyond the capacity of the ambulance service. From January 2013 to May 2015, 5,565 firefighters attended 1,866 "bariatric rescues" in the UK. Each call costs around £400.[25] The National Health Service has only a limited capacity for scanning obese people, meaning that obese patients often have to be sent to distant hospitals to be scanned.[26] Hospitals in Scotland installed 41 oversized mortuary fridges between 2013 and 2018 to cope with larger corpses.[27]

Tackling obesity

[edit]Various groups including government, food and health care professionals have made attempts to highlight and address the causes and growing problem of obesity in the United Kingdom.

School meals

[edit]In 2005, British chef Jamie Oliver began a campaign to reduce unhealthy food choices in British schools and to get children more enthused about eating lower calorie nutritious food instead. Oliver's efforts to bring radical change to the school meals system, chronicled in the series Jamie's School Dinners, challenged the junk-food culture by showing schools they could serve healthy, nutritious and cost-efficient meals that children enjoyed eating.[28] The British Government and Prime Minister Tony Blair promised to take steps to improve school dinners shortly after the programme aired. The programme prompted 271,677 people to sign an online petition on the Feed Me Better website, which was delivered to 10 Downing Street on 30 March 2005. As a result, the government added an extra £280 million ($316m USD) to help with the school meals plan.[29] Currently fried foods are only allowed to be served twice a week and soft drinks are no longer available.[30] However, there are no limits on the amount of sugar that can be legally consumed in the School Food Standards.[31] The Department for Education and Skills created the, now defunct,[32] School Food Trust, a £60 million initiative to provide support and advice to school administrators to improve the standard of school meals. Sugarwise found that some children have been exceeding the recommended sugar limits at schools, and in June 2019, introduced a certification scheme for school catering.[33]

Recommendations by medical professionals

[edit]In 2013, 220,000 doctors in the United Kingdom united to form what they call a 'prescription' for the UK's obesity epidemic. The report presented an action plan for future campaigning activity, setting out 10 recommendations for healthcare professionals, local and national government, industry and schools which it believed would help tackle the nation's obesity crisis.[34][35]

Recommendations included:

- Food-based standards to be mandatory in all UK hospitals

- A ban on new fast food outlets being located close to schools and colleges

- A duty on all sugary soft drinks, increasing the price by at least 20%, to be piloted

- Traffic light food labelling to include calorie information for children and adolescents – with visible calorie indicators for restaurants, especially fast food outlets

- £100m in each of the next three years to be spent on increasing provision of weight management services across the country

- A ban on advertising of foods high in saturated fats, sugar, and salt before 9pm

- Existing mandatory food- and nutrient-based standards in England to be statutory in free schools and academies

Action on Sugar, a registered UK charity and lobby group, was also formed in 2014 by a group of medical specialists concerned about sugar and its impact on health. Research by the group has highlighted the amount of added sugar contained in both processed food as well as drinks sold by national retailers such as Starbucks and Costa Coffee.[14][36] Despite this, the proposed sugar tax was squarely aimed at high-sugar drinks, particularly fizzy drinks, which are popular among teenagers. Pure fruit juices and milk-based drinks were excluded and the smallest producers had an exemption from the scheme.[37]

Government initiatives

[edit]In October 2011, British Prime Minister David Cameron told reporters that his government might consider a Fat tax as part of the solution to the United Kingdom's obesity problem.[38] A Public Health Responsibility Deal was subsequently announced in 2012 with voluntary pledges from the food industry and local business to promote healthy eating and physical activity.[39] The Public Health Responsibility Deal has been hailed by members of the UK's Food and Drink Federation and the Department of Health, but research published in 2015 by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine questioned the effectiveness of the voluntary agreement.[40] Policy based initiatives to improve diet, such as food pricing strategies, restrictions on marketing and the reduction of sugar intake, do not form a part of the pledges agreed by the food industry under the terms of the Public Health Responsibility Deal.[citation needed]

The government made efforts to use the London 2012 Summer Olympics to help tackle obesity and inspire people into a healthy active lifestyle. Health Secretary Alan Johnson set up Olympic themed Roadshows and mass participation events such as city runs. A £30 million grant was also issued to build cycle paths, playgrounds, and encourage children to cut out snacks.[41]

As a part of the London 2012 legacy, Prime Minister David Cameron also announced an annual £150 million ($227-USD) boost for school sport. The funding is "ring-fenced", meaning it can only be spent on sports activities such as after school clubs, coaching, and dedicated sports programmes.[42] Prompting criticism about mixed messaging, Official sponsors of the 2012 London Olympics included McDonald's, Coca-Cola, and Cadbury.[43]

In the 2016 United Kingdom budget, the British Government announced the introduction of a sugar tax on the soft drinks industry, which came into effect in April 2018. Beverage manufactures are taxed according to the volume of sugar sweetened beverages they produce or import. The measure would generate an estimated £520 million a year in additional tax revenue to be spent on doubling existing funding for sport in UK primary schools.[44]

Local authority initiatives

[edit]The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has published a review of the research on what local authorities can do to prevent and reduce obesity.[45] The review covers things that local authorities can do in the built and natural environments (e.g. increasing access to green spaces) and in the food environment (influencing what people buy and eat). The report covers interventions targeting active travel, public transport, leisure services, and public sports, as well as covering efforts in schools and the community, weight management programmes, and system-wide approaches.

General Practice

[edit]NICE guidelines recommend that in General Practice GPs aim to offer weight loss support to all patients with obesity, by sensitively asking for permission to discuss weight and proposing suitable treatments.[46] However in practice clinicians can be nervous about encountering patient resistance to this approach.[47]

Opportunistic weight loss discussions, where a GP engages in weight loss conversation, even though the patient did not attend the appointment for that reason, can be effective where doctors employ a positive communication style.[48] Resistance to these discussions can be avoided where the GP indicates knowledge of the personal situation of the patient and does not imply a lack of patient knowledge about weight loss.[47]

Statistics

[edit]In 2015, overweight and obese individuals in the United Kingdom were more likely to be found in urban settings, in contrast with those in the United States.[49] Statistics highlighted that lower income areas of London exhibit higher rates of childhood obesity compared with other parts of the UK. According to 2015 research data from the Health Survey for England, the proportion of children classified as overweight and obese was inversely related to household income.[50]

Data in 2022 noted that obesity in the UK cost the NHS about £40 billion per year.[51]

England

[edit]Data published in 2013 by London's Poverty Profile found disparities in childhood obesity rates between London and the rest of England, with 23% of children in London at the age of 10 to 11 being obese, higher than the English average.[52]

For England alone, Public Health England published data in May 2014 indicating that 63.8% of adults in England had a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or over with the most overweight region being the North East, where 68% of people were overweight, followed by the West Midlands at 65.7%.[53]

| Local Authority | County | Level of overweight or obese people (BMI ≥ 25) (2014) [53][54] |

|---|---|---|

| Copeland | Cumbria | 75.9% |

| Doncaster | South Yorkshire | 74.4% |

| East Lindsey | Lincolnshire | 73.8% |

| Ryedale | North Yorkshire | 73.7% |

| Sedgemoor | Somerset | 73.4% |

| Gosport | Hampshire | 72.9% |

| Castle Point | Essex | 72.8% |

| Bolsover | Derbyshire | 72.5% |

| Durham | County Durham | 72.5% |

| Milton Keynes | Buckinghamshire | 72.5% |

In 2021, the Health Survey for England estimated that 64% of adults were overweight or obese, with men and people aged over 45 making up most of those figures; it also noted that 22% of 4 year olds were overweight or obese, compared with 38% of 10 year olds.[55]

Another 2021 survey noted that all regions of England had a rate of at least 53%, with the highest rate being found among men in the North East, and the lowest rate among women in the South East.[56]

A 2023 survey looking at the healthiest and least healthy areas of the UK noted the following overweight/ obesity figures;

- Hartlepool 74.6%

- Knowsley (Liverpool) 74%

- Harlow 73.5%

- Gloucester 72.1%

- Gosport 71%

- Sandwell, West Midlands 70.8%

- Kingston upon Hull 70.7%

- Telford/Wrekin (Shropshire) 70.6%

- Blackpool 70.5%

- Great Yarmouth 68.7%

- Mansfield (Nottingham) 67.6%

- Nottingham 66.9%

- Lancaster 66.1%

- Liverpool 65.9%

- Portsmouth 65.4%

- Southampton 65%

- Peterborough 60.7%

- Melton (Leicestershire) 58.4%

In contrast, Richmond upon Thames had the lowest recorded rate of 45.5%.[57]

Northern Ireland

[edit]The Northern Ireland Department of Health released a study in 2024 showing that 65% of adults in NI were overweight or obese, compared to 26% of children.[58] The report noted that child obesity had gone down slightly in the past 10 years, while adult obesity had gone up by several percentage points. It was also noted that more men than women had high BMI numbers, with most people living in disadvantaged communities.[59] Previous reports have also noted a link between children living in deprived areas and child weight problems.[60]

In 2017, it was estimated that the lifetime costs of obesity in NI were €2.6bn (approx £2.1bn), including healthcare costs and loss of working hours.[61]

A University College London study in 2017 noted that NI had a higher rate of teenage obesity (40%) than the rest of the UK (37%).[62]

Statistics released in 2018 suggested that most incidents of obesity in NI were found in the Belfast City Council area, with high numbers also found in the Armagh/Banbridge/Craigavon, Antrim/Newtownabbey and Mid-East Antrim council areas.[63]

Scotland

[edit]In Scotland in 2019, 66% of adults aged 16+ were overweight or obese.[64]

Figures in 2022 showed that 67% of people in Scotland were overweight or obese, at a cost of £600 million to NHS Scotland;[65] it was also noted that 24% of four year olds were ‘at risk’ of being overweight or obese.

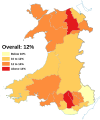

Wales

[edit]In 2012, it was reported that 57% of adults in Wales were obese or overweight.[66]

In 2019 Wales had the highest child obesity percentage out of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom and had a higher obesity rate than England.[67][66][68] One in eight reception age children in 2019 were reported to be obese[69] and 3.3% of children were severely obese.[70]

-

Percentage of reception age children that are severely obese in Wales in 2017/2018

-

Percentage of reception age children that are obese in Wales in 2017/2018

Figures from the National Survey for Wales in 2023 showed that 62% of adults in Wales were overweight or obese and it was estimated that this brought a cost of £73 million to the NHS in Wales.[71] It was also noted that nearly one-third of 4 year olds were overweight or obese.[72]

Comparison within Europe

[edit]| Country | Average weight in 2010 | BMI | Daily Calorie Intake | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 12 st 9 lb (80 kg) | 29 | 2,200 | [73] |

| Italy | 11 st 9 lb (74 kg) | 26 | 2,100 | |

| France | 10 st 9 lb (68 kg) | 24 | 2,200 | |

| Germany | 11 st 8 lb (73 kg) | 26 | 2,400 |

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study published in 2013, the United Kingdom had proportionately more obese and overweight adults than anywhere in western Europe with the exception of Iceland and Malta. Using data from 1980 to 2013, in the UK 66.6% of men and 52.7% of women were found to be either overweight or obese. The figures for Malta were 74.0% of men and 57.8% of women and for Iceland were 73.6% of men and 60.9% of women respectively.[74]

The UK had the fifth highest rate of obesity in Europe in 2015. 24.9% of the adult population had a body mass index of 30 or more.[75] In 2016 according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development nearly 27% of adults in the United Kingdom were obese, the highest proportion in Western Europe and a 92% increase since 1996.[76]

Data from 2019 suggested that the UK had the third highest level of obesity in Europe, after Romania and Croatia.[77]

Figures in 2024 showed that while UK was at 65%, only Croatia shared this statistic, with Hungary and Czechia showing rates of 60% and Romania going down to 59%.[78]

See also

[edit]- Health in the United Kingdom

- Obesity in the Republic of Ireland

- Epidemiology of obesity

- List of countries by Body Mass Index (BMI)

Cultural depictions

[edit]- Fictional characters: Billy Bunter, Dudley Dursley

References

[edit]- ^ Sparrow, Andrew (7 February 2016). "Childhood obesity is a national emergency, says Jeremy Hunt". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "Childhood obesity in England soars during pandemic". The Guardian. 2021-11-16. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ a b c d "Health Survey for England, 2018: Overweight and obesity in adults and children data tables". NHS Digital. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Wang, Y Claire; McPherson, Klim; Marsh, Tim; Gortmaker, Steven L.; Brown, Martin (2011). "Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK". The Lancet. 378 (9793): 815–825. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. PMID 21872750. S2CID 44240421.

- ^ Wang, Y Claire; McPherson, Klim; Marsh, Tim; Gortmaker, Steven L.; Brown, Martin (2011). "Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK". The Lancet. 378 (9793): 815–825. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. PMID 21872750. S2CID 44240421.

- ^ Foynes, Denise. "The 10 fattest countries in the world". Archived from the original on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ^ "10 Fattest countries in the developed world". Huffington Post. 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Local Authority Adult Excess Weight Prevalence Data". Obesity Data and Tools. Public Health England. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Bosely, Sarah (18 February 2013). "Obesity fightback begins in Tamworth, fat capital of Britain". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "What caused the obesity crisis in the West?". BBC News. 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Why Are 6 Of Top 7 Fattest Countries English Speaking Ones?". Medical News Today. MediLexicon International Ltd. 24 September 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Clark, Andrew (27 April 2007). "UK fat fears grill Burger King". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Armstrong, Ashley (7 November 2015). "Greggs' boss says global growth is 'impossible'". The Telegraph.

- ^ a b Brignall, Miles (17 February 2016). "The cafes serving drinks with 25 teaspoons of sugar per cup". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Green, Chris (2 April 2015). "Fast food Britain: The number of takeaways soars across the nation's high streets". The Independent.

- ^ "Nutritional Information Per Portion or Pack" (PDF). Cineworld Cinemas. p. 5. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- ^ Walker, Rob (2017-09-29). "Popcorn sales explosion makes it UK's fastest-growing grocery product". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ News Health, BBC (13 June 2012). "What caused the obesity crisis in the West?". BBC News.

- ^ "Britain: 'the fat man of Europe'". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Daneshkhu, Scheherazade (30 November 2015). "Commons health committee puts weight behind UK sugar tax". Financial Times. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Dobbs, Richard (5 July 2015). "The Obesity Crisis". The Cairo Review of Global Affairs. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Obesity bigger cost for Britain than war and terror". The Guardian. Press Association. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Germans: UK sperm fails to satisfy". BBC. 4 March 1999. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Obesity tied to poorer sperm quality". Reuters. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Thousands of obese people rescued from their own homes". The Times. 29 December 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ "Hospitals fail to invest in equipment to scan obese people". Guardian. 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ "Scottish mortuaries install larger fridges amid obesity crisis". Scotsman. 22 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ Kühn, Kerstin. "Jamie Oliver says school meals campaign is going as planned".

- ^ "TV chef welcomes £280m meals plan". BBC News. 30 March 2005.

- ^ Williams, Rachel (29 March 2010). "Jamie Oliver's school dinners shown to have improved academic results". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "UK schools implement Sugarwise certification scheme to slash high sugar consumption". .nutritioninsight.com/.

- ^ "Funds loss closes child food charity". 2017-07-24. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- ^ "Certification Scheme Show Schools Limit Sugar Intake". 24 June 2019.

- ^ Medical Royal Colleges, Academy Of. "Doctors Unite to deliver 'prescription' for UK Obesity epidemic".

- ^ Campbell, Denis (18 February 2013). "Obesity crisis: doctors demand soft drinks tax and healthier hospital food". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Action on Sugar, About Us". Action on Sugar. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ "Sugar tax: How will it work?". BBC News. 16 March 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Guardian, The (4 October 2011). "UK could introduce 'fat tax', says David Cameron". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Ng Fat, Linda (2015). "10" (PDF). Health Survey for England, 2014. Health and Social Care Information Centre. p. 2. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Denis (12 May 2015). "Food industry 'responsibility deal' has little effect on health, study finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Evening Standard, London. "Olympics at centre of new anti-obesity drive".

- ^ Mackay, Duncan. "Cameron announces £150 million boost for school sport as part of London 2012 legacy".

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (26 July 2012). "Olympics attacked for fast food and fizzy drink links". The Guardian.

- ^ Gander, Kashmira (17 March 2016). "Budget 2016: George Osborne announces sugar tax on soft drinks industry". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016.

- ^ "How can local authorities reduce obesity? Insights from NIHR research". NIHR Evidence. 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Overview | Obesity: identification, assessment and management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 2014-11-27. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b Tremblett, Madeleine; Webb, Helena; Ziebland, Sue; Stokoe, Elizabeth; Aveyard, Paul; Albury, Charlotte (2023-10-30). "The Basis of Patient Resistance to Opportunistic Discussions About Weight in Primary Care". Health Communication: 1–13. doi:10.1080/10410236.2023.2266622. ISSN 1041-0236. PMC 11404860.

- ^ Albury, Charlotte; Webb, Helena; Stokoe, Elizabeth; Ziebland, Sue; Koshiaris, Constantinos; Lee, Joseph J.; Aveyard, Paul (2023-11-07). "Relationship Between Clinician Language and the Success of Behavioral Weight Loss Interventions: A Mixed-Methods Cohort Study". Annals of Internal Medicine. 176 (11): 1437–1447. doi:10.7326/M22-2360. ISSN 0003-4819 – via LSE Research Online.

- ^ "The fat of the land: Mapping Obesity". The Economist. 19 December 2015.

- ^ Ng Fat, Linda (2015). "10" (PDF). Health Survey for England, 2014. Health and Social Care Information Centre. p. 1. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Obesity Action Scotland website, Obesity Prevalence, Causes and Impact, 2021-22

- ^ "London's Poverty Profile - Latest Poverty & Inequality Data for London".

- ^ a b "England's fattest areas: Copeland 'most overweight borough'". BBC News Online. 4 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ Williams, Rob (5 February 2014). "England's fattest areas revealed in shocking data that shows more than three-quarters of people in some areas are overweight or obese". The Independent. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ UK Parliament website, Commons Library Research Briefings, The Health Survey for England, retrieved September 29, 2024

- ^ Statista.com website, Share of overweight (including obese) individuals in England in 2021, by gender and region

- ^ Blue Horizon Blood Tests website, Healthiest Areas Index of The UK 2023, article dated August 19, 2023

- ^ NI government website, Health section, Obesity Strategy for Healthy Futures, page 12

- ^ BBC website, Obesity: Goal to make healthier food and drink more affordable, article dated February 21, 2024

- ^ Queen’s University Belfast website, Evidence is building to support a ‘whole systems approach’ to obesity prevention in Northern Ireland article dated January 26, 2023

- ^ Association for the Study of Obesity on the island of Ireland website, Epidemiology of Adult Obesity in Ireland by A. Courtney et al, 2020

- ^ Belfast Live website, ‘Northern Ireland has highest number of obese or overweight teens in UK’, article by Ella Pickover dated December 7, 2017

- ^ BBC website, Obesity-related deaths rise in Northern Ireland’, article dated November 1 2018

- ^ "Adult overweight and obesity". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ Obesity Action Scotland website, Obesity Prevalence, Causes and Impact, 2021-22

- ^ a b "Welsh health survey: 57% of adults overweight or obese". BBC News. 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ Smith, Mark (2019-03-07). "The parts of Wales with most obese children". WalesOnline. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ Wales, Public Health (2014-07-31). "NHS Wales | Child obesity rates higher in Wales than in England". www.wales.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ "Obesity in Wales (2019)". Public Health Wales. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ "Severely obese Welsh children numbers reach 1,000, figures show". BBC News. 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ Welsh parliament website, The rise in obesity: some food for thought, article dated March 7, 2024

- ^ NHS Wales website, Obesity 2021 figures

- ^ Freeman, Sarah (14 December 2010). "Obesity still eating away at health of the nation". Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Boseley, Sarah (29 May 2014). "UK among the worst in western Europe for level of overweight and obese people". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4473-1354-0.

- ^ "UK most obese country in Western Europe, says OECD report". Pharmaceutical Journal. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Statista.com website, Overweight and Obesity Rate in Europe, retrieved September 19, 2024

- ^ [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Overweight_and_obesity_-_BMI_ European Union website, Eurostat section, Overweight and Obesity - BMI Statistics, retrieved Sept 19, 2024