Nuclear medicine

| Nuclear medicine | |

|---|---|

A nuclear medicine PET scan | |

| ICD-10-PCS | C |

| ICD-9 | 92 |

| MeSH | D009683 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-70-3-72, 8-53 |

Nuclear medicine (nuclear radiology, nucleology),[1][2] is a medical specialty involving the application of radioactive substances in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Nuclear imaging is, in a sense, radiology done inside out, because it records radiation emitted from within the body rather than radiation that is transmitted through the body from external sources like X-ray generators. In addition, nuclear medicine scans differ from radiology, as the emphasis is not on imaging anatomy, but on the function. For such reason, it is called a physiological imaging modality. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are the two most common imaging modalities in nuclear medicine.[3]

Diagnostic medical imaging

[edit]Diagnostic

[edit]In nuclear medicine imaging, radiopharmaceuticals are taken internally, for example, through inhalation, intravenously, or orally. Then, external detectors (gamma cameras) capture and form images from the radiation emitted by the radiopharmaceuticals. This process is unlike a diagnostic X-ray, where external radiation is passed through the body to form an image.[citation needed]

There are several techniques of diagnostic nuclear medicine.

- 2D: Scintigraphy ("scint") is the use of internal radionuclides to create two-dimensional images.[4]

-

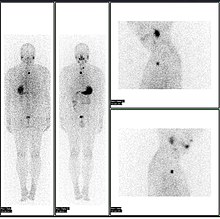

A nuclear medicine whole body bone scan. The nuclear medicine whole body bone scan is generally used in evaluations of various bone-related pathology, such as for bone pain, stress fracture, nonmalignant bone lesions, bone infections, or the spread of cancer to the bone.

-

Nuclear medicine myocardial perfusion scan with thallium-201 for the rest images (bottom rows) and Tc-Sestamibi for the stress images (top rows). The nuclear medicine myocardial perfusion scan plays a pivotal role in the non-invasive evaluation of coronary artery disease. The study not only identifies patients with coronary artery disease; it also provides overall prognostic information or overall risk of adverse cardiac events for the patient.

-

A nuclear medicine parathyroid scan demonstrates a parathyroid adenoma adjacent to the left inferior pole of the thyroid gland. The above study was performed with Technetium-Sestamibi (1st column) and iodine-123 (2nd column) simultaneous imaging and the subtraction technique (3rd column).

-

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan). The nuclear medicine hepatobiliary scan is clinically useful in the detection of the gallbladder disease.

-

Normal pulmonary ventilation and perfusion (V/Q) scan. The nuclear medicine V/Q scan is useful in the evaluation of pulmonary embolism.

-

Thyroid scan with iodine-123 for evaluation of hyperthyroidism.

- 3D: SPECT is a 3D tomographic technique that uses gamma camera data from many projections and can be reconstructed in different planes. Positron emission tomography (PET) uses coincidence detection to image functional processes.

-

A nuclear medicine SPECT liver scan with technetium-99m labeled autologous red blood cells. A focus of high uptake (arrow) in the liver is consistent with a hemangioma.

-

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) of a whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) acquisition of a 79 kg female after intravenous injection of 371 MBq of 18F-FDG (one hour prior measurement).

Nuclear medicine tests differ from most other imaging modalities in that nuclear medicine scans primarily show the physiological function of the system being investigated as opposed to traditional anatomical imaging such as CT or MRI. Nuclear medicine imaging studies are generally more organ-, tissue- or disease-specific (e.g.: lungs scan, heart scan, bone scan, brain scan, tumor, infection, Parkinson etc.) than those in conventional radiology imaging, which focus on a particular section of the body (e.g.: chest X-ray, abdomen/pelvis CT scan, head CT scan, etc.). In addition, there are nuclear medicine studies that allow imaging of the whole body based on certain cellular receptors or functions. Examples are whole body PET scans or PET/CT scans, gallium scans, indium white blood cell scans, MIBG and octreotide scans.

While the ability of nuclear metabolism to image disease processes from differences in metabolism is unsurpassed, it is not unique. Certain techniques such as fMRI image tissues (particularly cerebral tissues) by blood flow and thus show metabolism. Also, contrast-enhancement techniques in both CT and MRI show regions of tissue that are handling pharmaceuticals differently, due to an inflammatory process.

Diagnostic tests in nuclear medicine exploit the way that the body handles substances differently when there is disease or pathology present. The radionuclide introduced into the body is often chemically bound to a complex that acts characteristically within the body; this is commonly known as a tracer. In the presence of disease, a tracer will often be distributed around the body and/or processed differently. For example, the ligand methylene-diphosphonate (MDP) can be preferentially taken up by bone. By chemically attaching technetium-99m to MDP, radioactivity can be transported and attached to bone via the hydroxyapatite for imaging. Any increased physiological function, such as due to a fracture in the bone, will usually mean increased concentration of the tracer. This often results in the appearance of a "hot spot", which is a focal increase in radio accumulation or a general increase in radio accumulation throughout the physiological system. Some disease processes result in the exclusion of a tracer, resulting in the appearance of a "cold spot". Many tracer complexes have been developed to image or treat many different organs, glands, and physiological processes.

Hybrid scanning techniques

[edit]In some centers, the nuclear medicine scans can be superimposed, using software or hybrid cameras, on images from modalities such as CT or MRI to highlight the part of the body in which the radiopharmaceutical is concentrated. This practice is often referred to as image fusion or co-registration, for example SPECT/CT and PET/CT. The fusion imaging technique in nuclear medicine provides information about the anatomy and function, which would otherwise be unavailable or would require a more invasive procedure or surgery.

-

Normal whole body PET/CT scan with FDG-18. The whole body PET/CT scan is commonly used in the detection, staging and follow-up of various cancers.

-

Abnormal whole body PET/CT scan with multiple metastases from a cancer. The whole body PET/CT scan has become an important tool in the evaluation of cancer.

Practical concerns in nuclear imaging

[edit]Although the risks of low-level radiation exposures are not well understood, a cautious approach has been universally adopted that all human radiation exposures should be kept As Low As Reasonably Practicable, "ALARP". (Originally, this was known as "As Low As Reasonably Achievable" (ALARA), but this has changed in modern draftings of the legislation to add more emphasis on the "Reasonably" and less on the "Achievable".)

Working with the ALARP principle, before a patient is exposed for a nuclear medicine examination, the benefit of the examination must be identified. This needs to take into account the particular circumstances of the patient in question, where appropriate. For instance, if a patient is unlikely to be able to tolerate a sufficient amount of the procedure to achieve a diagnosis, then it would be inappropriate to proceed with injecting the patient with the radioactive tracer.

When the benefit does justify the procedure, then the radiation exposure (the amount of radiation given to the patient) should also be kept "ALARP". This means that the images produced in nuclear medicine should never be better than required for confident diagnosis. Giving larger radiation exposures can reduce the noise in an image and make it more photographically appealing, but if the clinical question can be answered without this level of detail, then this is inappropriate.

As a result, the radiation dose from nuclear medicine imaging varies greatly depending on the type of study. The effective radiation dose can be lower than or comparable to or can far exceed the general day-to-day environmental annual background radiation dose. Likewise, it can also be less than, in the range of, or higher than the radiation dose from an abdomen/pelvis CT scan.

Some nuclear medicine procedures require special patient preparation before the study to obtain the most accurate result. Pre-imaging preparations may include dietary preparation or the withholding of certain medications. Patients are encouraged to consult with the nuclear medicine department prior to a scan.

Analysis

[edit]The result of the nuclear medicine imaging process is a dataset comprising one or more images. In multi-image datasets the array of images may represent a time sequence (i.e. cine or movie) often called a "dynamic" dataset, a cardiac gated time sequence, or a spatial sequence where the gamma-camera is moved relative to the patient. SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) is the process by which images acquired from a rotating gamma-camera are reconstructed to produce an image of a "slice" through the patient at a particular position. A collection of parallel slices form a slice-stack, a three-dimensional representation of the distribution of radionuclide in the patient.

The nuclear medicine computer may require millions of lines of source code to provide quantitative analysis packages for each of the specific imaging techniques available in nuclear medicine.[citation needed]

Time sequences can be further analysed using kinetic models such as multi-compartment models or a Patlak plot.

Interventional nuclear medicine

[edit]Radionuclide therapy can be used to treat conditions such as hyperthyroidism, thyroid cancer, skin cancer and blood disorders.

In nuclear medicine therapy, the radiation treatment dose is administered internally (e.g. intravenous or oral routes) or externally direct above the area to treat in form of a compound (e.g. in case of skin cancer).

The radiopharmaceuticals used in nuclear medicine therapy emit ionizing radiation that travels only a short distance, thereby minimizing unwanted side effects and damage to noninvolved organs or nearby structures. Most nuclear medicine therapies can be performed as outpatient procedures since there are few side effects from the treatment and the radiation exposure to the general public can be kept within a safe limit.

| Substance | Condition |

|---|---|

| Iodine-131-sodium iodide | Hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer |

| Yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) and Iodine-131-tositumomab (Bexxar) | Refractory lymphoma |

| 131I-MIBG (metaiodobenzylguanidine) | Neuroendocrine tumors |

| Samarium-153 or Strontium-89 | Palliative bone pain treatment |

| Rhenium-188 | Squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma of the skin |

In some centers the nuclear medicine department may also use implanted capsules of isotopes (brachytherapy) to treat cancer.

| Radionuclide | Type | Half-life | Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caesium-137 (137Cs) | γ-ray | 30.17 years | 0.662 MeV |

| Cobalt-60 (60Co) | γ-ray | 5.26 years | 1.17, 1.33 MeV |

| Iridium-192 (192Ir) | β−-particles | 73.8 days | 0.38 MeV (mean) |

| Iodine-125 (125I) | γ-rays | 59.6 days | 27.4, 31.4 and 35.5 keV |

| Palladium-103 (103Pd) | γ-ray | 17.0 days | 21 keV (mean) |

| Ruthenium-106 (106Ru) | β−-particles | 1.02 years | 3.54 MeV |

History

[edit]The history of nuclear medicine contains contributions from scientists across different disciplines in physics, chemistry, engineering, and medicine. The multidisciplinary nature of nuclear medicine makes it difficult for medical historians to determine the birthdate of nuclear medicine. This can probably be best placed between the discovery of artificial radioactivity in 1934 and the production of radionuclides by Oak Ridge National Laboratory for medicine-related use, in 1946.[6]

The origins of this medical idea date back as far as the mid-1920s in Freiburg, Germany, when George de Hevesy made experiments with radionuclides administered to rats, thus displaying metabolic pathways of these substances and establishing the tracer principle. Possibly, the genesis of this medical field took place in 1936, when John Lawrence, known as "the father of nuclear medicine", took a leave of absence from his faculty position at Yale Medical School, to visit his brother Ernest Lawrence at his new radiation laboratory (now known as the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) in Berkeley, California. Later on, John Lawrence made the first application in patients of an artificial radionuclide when he used phosphorus-32 to treat leukemia.[7][8]

Many historians consider the discovery of artificially produced radionuclides by Frédéric Joliot-Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie in 1934 as the most significant milestone in nuclear medicine.[6] In February 1934, they reported the first artificial production of radioactive material in the journal Nature, after discovering radioactivity in aluminum foil that was irradiated with a polonium preparation. Their work built upon earlier discoveries by Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen for X-ray, Henri Becquerel for radioactive uranium salts, and Marie Curie (mother of Irène Curie) for radioactive thorium, polonium and coining the term "radioactivity." Taro Takemi studied the application of nuclear physics to medicine in the 1930s. The history of nuclear medicine will not be complete without mentioning these early pioneers.

Nuclear medicine gained public recognition as a potential specialty when on May 11, 1946, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by Massachusetts General Hospital's Dr. Saul Hertz and Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Dr. Arthur Roberts, described the successful use of treating Graves' Disease with radioactive iodine (RAI) was published.[9] Additionally, Sam Seidlin.[10] brought further development in the field describing a successful treatment of a patient with thyroid cancer metastases using radioiodine (I-131). These articles are considered by many historians as the most important articles ever published in nuclear medicine.[11] Although the earliest use of I-131 was devoted to therapy of thyroid cancer, its use was later expanded to include imaging of the thyroid gland, quantification of the thyroid function, and therapy for hyperthyroidism. Among the many radionuclides that were discovered for medical-use, none were as important as the discovery and development of Technetium-99m. It was first discovered in 1937 by C. Perrier and E. Segre as an artificial element to fill space number 43 in the Periodic Table. The development of a generator system to produce Technetium-99m in the 1960s became a practical method for medical use. Today, Technetium-99m is the most utilized element in nuclear medicine and is employed in a wide variety of nuclear medicine imaging studies.

Widespread clinical use of nuclear medicine began in the early 1950s, as knowledge expanded about radionuclides, detection of radioactivity, and using certain radionuclides to trace biochemical processes. Pioneering works by Benedict Cassen in developing the first rectilinear scanner and Hal O. Anger's scintillation camera (Anger camera) broadened the young discipline of nuclear medicine into a full-fledged medical imaging specialty.

By the early 1960s, in southern Scandinavia, Niels A. Lassen, David H. Ingvar, and Erik Skinhøj developed techniques that provided the first blood flow maps of the brain, which initially involved xenon-133 inhalation;[12] an intra-arterial equivalent was developed soon after, enabling measurement of the local distribution of cerebral activity for patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.[13] Later versions would have 254 scintillators so a two-dimensional image could be produced on a color monitor. It allowed them to construct images reflecting brain activation from speaking, reading, visual or auditory perception and voluntary movement.[14] The technique was also used to investigate, e.g., imagined sequential movements, mental calculation and mental spatial navigation.[15][16]

By the 1970s most organs of the body could be visualized using nuclear medicine procedures. In 1971, American Medical Association officially recognized nuclear medicine as a medical specialty.[17] In 1972, the American Board of Nuclear Medicine was established, and in 1974, the American Osteopathic Board of Nuclear Medicine was established, cementing nuclear medicine as a stand-alone medical specialty.

In the 1980s, radiopharmaceuticals were designed for use in diagnosis of heart disease. The development of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), around the same time, led to three-dimensional reconstruction of the heart and establishment of the field of nuclear cardiology.

More recent developments in nuclear medicine include the invention of the first positron emission tomography scanner (PET). The concept of emission and transmission tomography, later developed into single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), was introduced by David E. Kuhl and Roy Edwards in the late 1950s.[citation needed] Their work led to the design and construction of several tomographic instruments at the University of Pennsylvania. Tomographic imaging techniques were further developed at the Washington University School of Medicine. These innovations led to fusion imaging with SPECT and CT by Bruce Hasegawa from University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and the first PET/CT prototype by D. W. Townsend from University of Pittsburgh in 1998.[citation needed]

PET and PET/CT imaging experienced slower growth in its early years owing to the cost of the modality and the requirement for an on-site or nearby cyclotron. However, an administrative decision to approve medical reimbursement of limited PET and PET/CT applications in oncology has led to phenomenal growth and widespread acceptance over the last few years, which also was facilitated by establishing 18F-labelled tracers for standard procedures, allowing work at non-cyclotron-equipped sites. PET/CT imaging is now an integral part of oncology for diagnosis, staging and treatment monitoring. A fully integrated MRI/PET scanner is on the market from early 2011.[citation needed]

Sources of radionuclides

[edit]99mTc is normally supplied to hospitals through a radionuclide generator containing the parent radionuclide molybdenum-99. 99Mo is typically obtained as a fission product of 235U in nuclear reactors, however global supply shortages have led to the exploration of other methods of production. About a third of the world's supply, and most of Europe's supply, of medical isotopes is produced at the Petten nuclear reactor in the Netherlands. Another third of the world's supply, and most of North America's supply, was produced at the Chalk River Laboratories in Chalk River, Ontario, Canada until its permanent shutdown in 2018.[18]

The most commonly used radioisotope in PET, 18F, is not produced in a nuclear reactor, but rather in a circular accelerator called a cyclotron. The cyclotron is used to accelerate protons to bombard the stable heavy isotope of oxygen 18O. The 18O constitutes about 0.20% of ordinary oxygen (mostly oxygen-16), from which it is extracted. The 18F is then typically used to make FDG.

| Isotope | Z | T1/2 | Decay mode |

Gamma energy (keV) |

Maximum β energy (keV) / Abundance[22] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Symbol | |||||

| Imaging | ||||||

| fluorine-18 | 18F | 9 | 109.77 m | β+ | 511 (193%) | 634 (97%) |

| gallium-67 | 67Ga | 31 | 3.26 d | ec | 93 (39%), 185 (21%), 300 (17%) |

- |

| krypton-81m | 81mKr | 36 | 13.1 s | IT | 190 (68%) | - |

| rubidium-82 | 82Rb | 37 | 1.27 m | β+ | 511 (191%) | 3381 (81.8%) 2605 (13.1%) 1906 (0.14%) 1209 (0.32%) |

| nitrogen-13 | 13N | 7 | 9.97 m | β+ | 511 (200%) | 1198 (99.8%) |

| technetium-99m | 99mTc | 43 | 6.01 h | IT | 140 (89%) | - |

| indium-111 | 111In | 49 | 2.80 d | ec | 171 (90%), 245 (94%) |

- |

| iodine-123 | 123I | 53 | 13.3 h | ec | 159 (83%) | - |

| xenon-133 | 133Xe | 54 | 5.24 d | β− | 81 (31%) | 346 (99.1%) 267 (0.9%) |

| thallium-201 | 201Tl | 81 | 3.04 d | ec | 69–83* (94%), 167 (10%) |

- |

| Therapy | ||||||

| yttrium-90 | 90Y | 39 | 2.67 d | β− | - | 2279 (99.98%) |

| iodine-131 | 131I | 53 | 8.02 d | β− | 364 (81%) | 807 (0.4%) 606 (89.4%) 334 (7.2%) 248 (2.1%) |

| lutetium-177 | 177Lu | 71 | 6.65 d | β− | 113 (6.6%) 208 (11%) |

498 (79.3%) 385 (9.1%) 177 (11.6%) |

|

Z = atomic number, the number of protons | ||||||

A typical nuclear medicine study involves administration of a radionuclide into the body by intravenous injection in liquid or aggregate form, ingestion while combined with food, inhalation as a gas or aerosol, or rarely, injection of a radionuclide that has undergone micro-encapsulation. Some studies require the labeling of a patient's own blood cells with a radionuclide (leukocyte scintigraphy and red blood cell scintigraphy). Most diagnostic radionuclides emit gamma rays either directly from their decay or indirectly through electron–positron annihilation, while the cell-damaging properties of beta particles are used in therapeutic applications. Refined radionuclides for use in nuclear medicine are derived from fission or fusion processes in nuclear reactors, which produce radionuclides with longer half-lives, or cyclotrons, which produce radionuclides with shorter half-lives, or take advantage of natural decay processes in dedicated generators, i.e. molybdenum/technetium or strontium/rubidium.

The most commonly used intravenous radionuclides are technetium-99m, iodine-123, iodine-131, thallium-201, gallium-67, fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose, and indium-111 labeled leukocytes.[citation needed] The most commonly used gaseous/aerosol radionuclides are xenon-133, krypton-81m, (aerosolised) technetium-99m.[23]

Policies and procedures

[edit]Radiation dose

[edit]A patient undergoing a nuclear medicine procedure will receive a radiation dose. Under present international guidelines it is assumed that any radiation dose, however small, presents a risk. The radiation dose delivered to a patient in a nuclear medicine investigation, though unproven, is generally accepted to present a very small risk of inducing cancer. In this respect it is similar to the risk from X-ray investigations except that the dose is delivered internally rather than from an external source such as an X-ray machine, and dosage amounts are typically significantly higher than those of X-rays.

The radiation dose from a nuclear medicine investigation is expressed as an effective dose with units of sieverts (usually given in millisieverts, mSv). The effective dose resulting from an investigation is influenced by the amount of radioactivity administered in megabecquerels (MBq), the physical properties of the radiopharmaceutical used, its distribution in the body and its rate of clearance from the body.

Effective doses can range from 6 μSv (0.006 mSv) for a 3 MBq chromium-51 EDTA measurement of glomerular filtration rate to 11.2 mSv (11,200 μSv) for an 80 MBq thallium-201 myocardial imaging procedure. The common bone scan with 600 MBq of technetium-99m MDP has an effective dose of approximately 2.9 mSv (2,900 μSv).[24]

Formerly, units of measurement were:

- the curie (Ci), equal to 3.7 × 1010 Bq, and also equal to 1.0 grams of radium (Ra-226);

- the rad (radiation absorbed dose), now replaced by the gray; and

- the rem (Röntgen equivalent man), now replaced by the sievert.[25]

The rad and rem are essentially equivalent for almost all nuclear medicine procedures, and only alpha radiation will produce a higher Rem or Sv value, due to its much higher Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE). Alpha emitters are nowadays rarely used in nuclear medicine, but were used extensively before the advent of nuclear reactor and accelerator produced radionuclides. The concepts involved in radiation exposure to humans are covered by the field of Health Physics; the development and practice of safe and effective nuclear medicinal techniques is a key focus of Medical Physics.

Regulatory frameworks and guidelines

[edit]Different countries around the world maintain regulatory frameworks that are responsible for the management and use of radionuclides in different medical settings. For example, in the US, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have guidelines in place for hospitals to follow.[26] With the NRC, if radioactive materials aren't involved, like X-rays for example, they are not regulated by the agency and instead are regulated by the individual states.[27] International organizations, such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), have regularly published different articles and guidelines for best practices in nuclear medicine as well as reporting on emerging technologies in nuclear medicine.[28][29] Other factors that are considered in nuclear medicine include a patient's medical history as well as post-treatment management. Groups like International Commission on Radiological Protection have published information on how to manage the release of patients from a hospital with unsealed radionuclides.[30]

See also

[edit]- Human subject research

- List of Nuclear Medicine Societies

- Nuclear medicine physician

- Nuclear pharmacy

- Nuclear technology

- Radiographer

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.texaschildrens.org/departments/nuclear-radiology

- ^ What is nucleology?

- ^ "Nuclear Medicine". Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ scintigraphy Citing: Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers, 2007 by Saunders; Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, 3 ed. 2007; McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine, 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies

- ^ "Nuclear Wallet Cards". Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ a b Edwards, C. L. (1979). "Tumor-localizing radionuclides in retrospect and prospect". Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 9 (3): 186–9. doi:10.1016/s0001-2998(79)80030-6. PMID 388628.

- ^ Donner Laboratory: The Birthplace of. Nuclear Medicine

- ^ "Important Moments in the History of Nuclear Medicine". Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ Hertz S, Roberts A (May 1946). "Radioactive iodine in the study of thyroid physiology; the use of radioactive iodine therapy in hyperthyroidism". Journal of the American Medical Association. 131: 81–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1946.02870190005002. PMID 21025609.

- ^ Seidlin SM, Marinelli LD, Oshry E (December 1946). "Radioactive iodine therapy; effect on functioning metastases of adenocarcinoma of the thyroid". Journal of the American Medical Association. 132 (14): 838–47. doi:10.1001/jama.1946.02870490016004. PMID 20274882.

- ^ Henkin R, et al. (1996). Nuclear Medicine (First ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-8016-7701-4.

- ^ Lassen NA, Ingvar DH [in Swedish] (1961). "Quantitative determination of regional cerebral blood-flow in man". The Lancet. 278 (7206): 806–807. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(61)91092-3.

- ^ Ingvar DH [in Swedish], Franzén G (December 1974). "Distribution of cerebral activity in chronic schizophrenia". Lancet. 2 (7895): 1484–6. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90221-9. PMID 4140398.

- ^ Lassen NA, Ingvar DH [in Swedish], Skinhøj E [in Danish] (October 1978). "Brain Function and Blood Flow". Scientific American. 239 (4): 62–71. Bibcode:1978SciAm.239d..62L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1078-62. PMID 705327.

- ^ Roland PE [in Swedish], Larsen B, Lassen NA, Skinhøj E [in Danish] (January 1980). "Supplementary motor area and other cortical areas in organization of voluntary movements in man". Journal of Neurophysiology. 43 (1): 118–36. doi:10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.118. PMID 7351547.

- ^ Roland PE [in Swedish], Friberg L [in Swedish] (1985). "Localization of cortical areas activated by thinking". Journal of Neurophysiology. Vol. 53, no. 5. pp. 1219–1243.

- ^ "What is nuclear medicine" (PDF). Society of Nuclear Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-17. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ "Canada permanently closes NRU research reactor". Nuclear Engineering International. 6 April 2018.

- ^ Eckerman KF, Endo A: MIRD: Radionuclide Data and Decay Schemes. Society for Nuclear Medicine, 2008. ISBN 978-0-932004-80-2

- ^ Table of Radioactive Isotopes Archived 2004-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dash A, Pillai MR, Knapp FF (June 2015). "Production of (177)Lu for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: Available Options". Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 49 (2): 85–107. doi:10.1007/s13139-014-0315-z. PMC 4463871. PMID 26085854.

- ^ "Données atomiques et nucléaires". Laboratoire National Henri Becquerel. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Technegas a radioaerosol invented in Australia by Dr Bill Burch and Dr Richard Fawdry

- ^ Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee (19 February 2021). "ARSAC notes for guidance" (pdf). GOV.UK. Public Health England.

- ^ Chandler, David (2011-03-28). "Explained: rad, rem, sieverts, becquerels". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Le, Dao (2021), Wong, Franklin C.L. (ed.), "An Overview of the Regulations of Radiopharmaceuticals", Locoregional Radionuclide Cancer Therapy: Clinical and Scientific Aspects, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 225–247, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56267-0_10, ISBN 978-3-030-56267-0, S2CID 230547683, retrieved 2021-04-25

- ^ "Nuclear Medicine: What It Is – and Isn't". NRC Web. 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ "IAEA Safety Standards and medical exposure". www.iaea.org. 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ "Human Health Campus – Nuclear Medicine". humanhealth.iaea.org. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ International Commission on Radiological Protection (June 2004). "Release of patients after therapy with unsealed radionuclides". Annals of the ICRP. 34 (2): v–vi. doi:10.1016/j.icrp.2004.08.001. ISSN 0146-6453. PMID 15571759. S2CID 43014655.

Further reading

[edit]- Mas JC (2008). A Patient's Guide to Nuclear Medicine Procedures: English-Spanish. Society of Nuclear Medicine. ISBN 978-0-9726478-9-2.

- Taylor A, Schuster DM, Naomi Alazraki N (2000). A Clinicians' Guide to Nuclear Medicine (2nd ed.). Society of Nuclear Medicine. ISBN 978-0-932004-72-7.

- Shumate MJ, Kooby DA, Alazraki NP (2007). A Clinician's Guide to Nuclear Oncology: Practical Molecular Imaging and Radionuclide Therapies. Society of Nuclear Medicine. ISBN 978-0-9726478-8-5.

- Ell P, Gambhir S (2004). Nuclear Medicine in Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment. Churchill Livingstone. p. 1950. ISBN 978-0-443-07312-0.

- Jones DW, Hogg P, Seeram E (2013). Practical SPECT/CT In Nuclear Medicine. Springer. ISBN 978-1447147022.

External links

[edit]- Solving the Medical Isotope Crisis Hearing before the Subcommittee on Energy and Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session, September 9, 2009