Fallout shelter

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designated to protect occupants from radioactive debris or fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the Cold War.

During a nuclear explosion, matter vaporized in the resulting fireball is exposed to neutrons from the explosion, absorbs them, and becomes radioactive. When this material condenses in the rain, it forms dust and light sandy materials that resemble ground pumice. The fallout emits alpha and beta particles, as well as gamma rays.

Much of this highly radioactive material falls to Earth, subjecting anything within the line of sight to radiation, becoming a significant hazard. A fallout shelter is designed to allow its occupants to minimize exposure to harmful fallout until radioactivity has decayed to a safer level, over a few weeks or months.

Principle

[edit]A fallout shelter is designed to protect its occupants from:

- the mechanical and thermal effects of a nuclear explosion (or nuclear accident);[1]

- radioactive fallout, allowing them to survive for a period of time deemed sufficient to allow them to escape safely.

History

[edit]North America

[edit]

During the Cold War, many countries built fallout shelters for high-ranking government officials and crucial military facilities, such as Project Greek Island and the Cheyenne Mountain nuclear bunker in the United States and Canada's Emergency Government Headquarters. Plans were made, however, to use existing buildings with sturdy below-ground-level basements as makeshift fallout shelters. These buildings were placarded with the orange-yellow and black trefoil sign designed by United States Army Corps of Engineers director of administrative logistics support function Robert W. Blakeley in 1961.[2]

The National Emergency Alarm Repeater (NEAR) program was developed in the United States in 1956 during the Cold War to supplement the existing siren warning systems and radio broadcasts in the event of a nuclear attack. The NEAR civilian alarm device was engineered and tested but the program was not viable and was terminated in 1967.[3]

In the U.S. in September 1961, under the direction of Steuart L. Pittman, the federal government started the Community Fallout Shelter Program.[4][5] A letter from President Kennedy advising the use of fallout shelters appeared in the September 1961 issue of Life magazine.[6] From 1961 to 1963, home fallout shelter sales grew, but eventually[when?] there was a public backlash against the fallout shelter as a consumer product.[7]

In November 1961, in Fortune magazine, an article by Gilbert Burck appeared that outlined the plans of Nelson Rockefeller, Edward Teller, Herman Kahn, and Chet Holifield for an enormous network of concrete-lined underground fallout shelters throughout the United States sufficient to shelter millions of people to serve as a refuge in case of nuclear war.[8]

The United States ended federal funding for the shelters in the 1970s.[9] In 2017, New York City began removing the yellow signs since members of the public are unlikely to find edible food and usable medicine inside those rooms.[10]

Atomitat

[edit]The Atomitat was an underground house in Plainview, Texas: it was designed by Jay Swayze and completed in 1962. The house was designed in response to the fear of nuclear war during the Cold War. The house was designed to be an "atomic-habitat" which met the United States Civil Defense specifications.[11] It was the first bunker-house to meet their specifications as a nuclear shelter.[12] Swayze also built an underground house for the 1964 New York World's Fair: it was called the Underground World Home.[13]

Europe

[edit]Similar projects have been undertaken in Finland, which requires all buildings with area over 600 m2 to have an NBC (nuclear-biological-chemical) shelter, and Norway, which requires all buildings with an area over 1000 m2 to have a shelter.[14]

The former Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries often designed their underground mass-transit and subway tunnels to serve as bomb and fallout shelters in the event of an attack. Currently, the deepest subway line in the world is situated in St Petersburg in Russia, with an average depth of 60 meters, while the deepest subway station is Arsenalna in Kyiv, at 105.5 meters.[15]

Germany has protected shelters for 3% of its population, Austria for 30%, Finland for 70%, Sweden for 81%,[16] and Switzerland for 114%.[17]

Bosnia

[edit]

The Armijska Ratna Komanda D-0, also known as the Ark,[18] was a Cold War-era nuclear bunker and military command centre located near the town of Konjic[19] in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[20] Built to protect Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito and up to 350 members of his inner circle[18] in the event of an atomic exchange, the structure is made up of residential areas, conference rooms, offices, strategic planning rooms, and other areas.[20] The bunker remained a state secret until after the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[21]

The facility is now under the authority of the Bosnian Ministry of Defense and is managed by the country's military, guarded by a five-soldier detachment,[18] but is designated by KONS as National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina and used as exhibition space for project such as Cultural Event of Europe with strong UNESCO support, and tourist attraction.[20]

Another underground facility is Željava Air Base, situated on the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia under the Gola Plješevica mountain, near the city of Bihać. It was the largest underground airport and military air base in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), and one of the largest in Europe. The role of the facility was to establish, integrate and coordinate a nationwide early warning radar network in SFRY akin to NORAD in the US. The complex contained tunnels in total length of 3.5 km (2.2 mi), and the bunker with four entrances protected by 100-ton pressurized doors, three of which were customized for use by fixed-wing aircraft. capable in housing two full fighter squadrons, one reconnaissance squadron, and associated maintenance facilities. It was designed and built to sustain a direct hit from a 20-kiloton nuclear bomb, equivalent to that dropped on Nagasaki. The underground facility was lined with semicircular concrete shields, arranged every 10 km (6.2 mi), to cushion the impact of incoming strike. The complex included an underground water source, power generators, crew quarters, and other strategic military facilities. It also housed a mess hall that could feed 1,000 people simultaneously, along with stores of food, fuel and arms sufficient to last 30 days. Fuel was supplied by a 20 km (12 mi) underground pipe network connected to a military warehouse on Pokoj Hill near Bihać. Nowadays, they are popular for urban exploration.[22][23][24]

Switzerland

[edit]

Switzerland built an extensive network of fallout shelters, not only through extra hardening of government buildings such as schools, but also through a building regulation requiring nuclear shelters in residential buildings since the 1960s (the first legal basis in this sense dates from 4 October 1963).[25] Later, the law ensured that all residential buildings built after 1978 contained a nuclear shelter able to withstand a blast from a 12-megaton explosion at a distance of 700 metres.[26] The Federal Law on the Protection of the Population and Civil Protection still requires that every inhabitant should have a place in a shelter close to where they live.[17]

The Swiss authorities maintained large communal shelters (such as the Sonnenberg Tunnel until 2006) stocked with over four months of food and fuel.[26] The reference Nuclear War Survival Skills declared that, as of 1986, "Switzerland has the best civil defense system, one that already includes blast shelters for over 85% of all its citizens."[27] As of 2006, there were about 300,000 shelters built in private residences, institutions and hospitals, as well as 5,100 public shelters for a total of 8.6 million places, a level of coverage equal to 114% of the population.[17]

In Switzerland, most residential shelters are no longer stocked with the food and water required for prolonged habitation and a large number have been converted by the owners to other uses (e.g., wine cellars, ski rooms, gyms),[26] but a legal obligation to ensure that the shelters are properly maintained remains in effect.[17]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, a network of fallout shelters were built across the country for use by the Royal Observer Corps in its nuclear reporting role.[28] Other shelters were built for the purposes of the ROTOR radar system[29] and the regional seat of government scheme.[30] The Pindar complex in London is intended to provide its inhabitants with fallout protection in the event of nuclear attack,[31] as was the earlier Central Government War Headquarters in Corsham.[32]

Details of shelter construction

[edit]

Shielding

[edit]A basic fallout shelter consists of shields that reduce gamma ray exposure by a factor of 1000. The required shielding can be accomplished with 10 times the thickness of any quantity of material capable of cutting gamma ray exposure in half. Shields that reduce gamma ray intensity by 50% (1/2) include 1 centimetre (0.4 in) of lead, 6 cm (2.4 in) of concrete, 9 cm (3.5 in) of packed earth or 150 metres (500 ft) of air. When multiple thicknesses are built, the shielding multiplies. Thus, a practical fallout shield is ten halving-thicknesses of packed earth, reducing gamma rays by approximately 1024 times (210).[33]

Usually, an expedient purpose-built fallout shelter is a trench; with a strong roof buried by 1 m (3 ft) of earth. The two ends of the trench have ramps or entrances at right angles to the trench, so that gamma rays cannot enter (they can travel only in straight lines). To make the overburden waterproof (in case of rain), a plastic sheet may be buried a few inches below the surface and held down with rocks or bricks.[34]

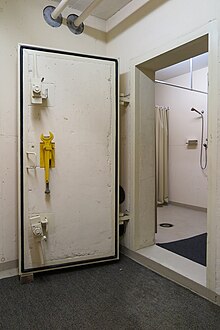

Blast doors are designed to absorb the shock wave of a nuclear blast, bending and then returning to their original shape.[35]

Climate control

[edit]Dry earth is a reasonably good thermal insulator, but over several weeks of habitation, a shelter will become dangerously hot.[36] The simplest form of effective fan to cool a shelter is a wide, heavy frame with flaps that swing in the shelter's doorway and can be swung from hinges on the ceiling. The flaps open in one direction and close in the other, pumping air. (This is a Kearny air pump, or KAP, named after the inventor, Cresson Kearny.)

Unfiltered air is safe, since the most dangerous fallout has the consistency of sand or finely ground pumice.[36] Such large particles are not easily ingested into the soft tissues of the body, so extensive filters are not required. Any exposure to fine dust is far less hazardous than exposure to the fallout outside the shelter. Dust fine enough to pass the entrance will probably pass through the shelter.[36] Some shelters, however, incorporate NBC-filters for additional protection.

Locations

[edit]Effective public shelters can be the middle floors of some tall buildings or parking structures, or below ground level in most buildings with more than 10 floors. The thickness of the upper floors must form an effective shield, and the windows of the sheltered area must not view fallout-covered ground that is closer than 1.5 km (1 mi). One of Switzerland's solutions is to use road tunnels passing through the mountains, with some of these shelters being able to protect tens of thousands.[37]

Fallout shelters are not always underground. Above ground buildings with walls and roofs dense enough to afford a meaningful protection factor can be used as a fallout shelter.[38]

Contents

[edit]A battery-powered radio may be helpful to get reports of fallout patterns and clearance. However, radio and other electronic equipment may be disabled by electromagnetic pulse. For example, even at the height of the Cold War, EMP protection had been completed for only 125 of the approximately 2,771 radio stations in the United States Emergency Broadcast System. Also, only 110 of 3,000 existing Emergency Operating Centers had been protected against EMP effects.[39] The Emergency Broadcast System has since been supplanted in the United States by the Emergency Alert System.

The reference Nuclear War Survival Skills includes the following supplies in a list of "Minimum Pre-Crisis Preparations": one or more shovels, a pick, a bow-saw with an extra blade, a hammer, and 0.1 mm (4 mils) polyethylene film (also any necessary nails, wire, etc.); a homemade shelter-ventilating pump (a KAP); large containers for water; a plastic bottle of sodium hypochlorite bleach; one or two KFMs (Kearny fallout meters) and the knowledge to operate them; at least a 2-week supply of compact, nonperishable food; an efficient portable stove; wooden matches in a waterproof container; essential containers and utensils for storing, transporting, and cooking food; a hose-vented 20 litres (5 US gal) can, with heavy plastic bags for liners, for use as a toilet; tampons; insect screen and fly bait; any special medications needed by family members; pure potassium iodide, a 60 mL (2 US fl oz) bottle, and a medicine dropper; a first-aid kit and a tube of antibiotic ointment; long-burning candles (with small wicks) sufficient for at least 14 nights; an oil lamp; a flashlight and extra batteries; and a transistor radio with extra batteries and a metal box to protect it from electromagnetic pulse.[40]

Inhabitants should have water on hand, 4–8 litres (1–2 US gal) per person per day. Water stored in bulk containers requires less space than water stored in smaller bottles.[41]

Kearny fallout meter

[edit]Commercially made Geiger counters are expensive and require frequent calibration. It is possible to construct an electrometer-type radiation meter called the Kearny fallout meter, which does not require batteries or professional calibration, from properly-scaled plans with just a coffee can or pail, gypsum board, monofilament fishing line, and aluminum foil.[42] Plans are freely available in the public domain in the reference Nuclear War Survival Skills by Cresson Kearny.[43]

Use

[edit]Inhabitants should plan to remain sheltered for at least two weeks (with an hour out at the end of the first week – see Swiss Civil Defense guidelines), then work outside for gradually increasing amounts of time, to four hours a day at three weeks. The normal work is to sweep or wash fallout into shallow trenches to decontaminate the area. They should sleep in a shelter for several months. Evacuation at three weeks is recommended by official authorities.[citation needed]

If available, inhabitants may take potassium iodide at the rate of 130 mg/day per adult (65 mg/day per child) as an additional measure to protect the thyroid gland from the uptake of dangerous radioactive iodine, a component of most fallout and reactor waste.[44]

|

|

|

|

|

Different types of radiation emitted by fallout

[edit]Alpha (α)

[edit]In the vast majority of accidents, and in all atomic bomb blasts, the threat due to beta and gamma emitters is greater than that posed by the alpha emitters in the fallout. Alpha particles are identical to a helium-4 nucleus (two protons and two neutrons), and travel at speeds in excess of 5% of the speed of light. Alpha particles have little penetrating power; most cannot penetrate through human skin. Avoiding direct exposure with fallout particles will prevent injury from alpha radiation.[46]

Beta (β)

[edit]Beta radiation consists of particles (high-speed electrons) given off by some fallout. Most beta particles cannot penetrate more than about 3 metres (10 ft) of air or about 3 mm (1⁄8 in) of water, wood, or human body tissue; or a sheet of aluminum foil. Avoiding direct exposure with fallout particles will prevent most injuries from beta radiation.[47]

The primary dangers associated with beta radiation are internal exposure from ingested fallout particles and beta burns from fallout particles no more than a few days old. Beta burns can result from contact with highly radioactive particles on bare skin; ordinary clothing separating fresh fallout particles from the skin can provide significant shielding.[47]

Gamma (γ)

[edit]Gamma radiation penetrates further through matter than alpha or beta radiation. Most of the design of a typical fallout shelter is intended to protect against gamma rays. Gamma rays are better absorbed by materials with high atomic numbers and high density, although neither effect is important compared to the total mass per area in the path of the gamma ray. Thus, lead is only modestly better as a gamma shield than an equal mass of another shielding material such as aluminum, concrete, water or soil.

Some gamma radiation from fallout will penetrate into even the best shelters. However, the radiation dose received while inside a shelter can be significantly reduced with proper shielding. Ten halving thicknesses of a given material can reduce gamma exposure to less than 1⁄1000 of unshielded exposure.[48]

Weapons versus nuclear accident fallout

[edit]The bulk of the radioactivity in nuclear accident fallout is more long-lived than that in weapons fallout. A good table of the nuclides, such as that provided by the Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute, includes the fission yields of the different nuclides. From this data it is possible to calculate the isotopic mixture in the fallout (due to fission products in bomb fallout).[citation needed]

Other matters and simple improvements

[edit]While a person's home may not be a purpose-made shelter, it could be thought of as one if measures are taken to improve the degree of fallout protection.

Measures to lower the beta dose

[edit]The main threat of beta radiation exposure comes from hot particles in contact with or close to the skin of a person. Also, swallowed or inhaled hot particles could cause beta burns. As it is important to avoid bringing hot particles into the shelter, one option is to remove one's outer clothing, or follow other decontamination procedures, on entry. Fallout particles will cease to be radioactive enough to cause beta burns within a few days following a nuclear explosion. The danger of gamma radiation will persist for far longer than the threat of beta burns in areas with heavy fallout exposure.[49]

Measures to lower the gamma dose rate

[edit]The gamma dose rate due to the contamination brought into the shelter on the clothing of a person is likely to be small (by wartime standards) compared to gamma radiation that penetrates through the walls of the shelter.[49] The following measures can be taken to reduce the amount of gamma radiation entering the shelter:

- Roofs and gutters can be cleaned to lower the dose rate in the house.

- The top inch of soil in the area near the house can be either removed or dug up and mixed with the subsoil. This reduces the dose rate as the gamma rays have to pass through the topsoil before they can irradiate anything above.

- Nearby roads can be rinsed and washed down to remove dust and debris; the fallout would collect in the sewers and gutters for easier disposal. In Kyiv after the Chernobyl accident a program of road washing was used to control the spread of radioactivity.

- Windows can be bricked up, or the sill raised to reduce the hole in the shielding formed by the wall.

- Gaps in the shielding can be blocked using containers of water. While water has a much lower density than that of lead, it is still able to shield some gamma rays.

- Earth (or other dense material) can be heaped up against the exposed walls of the building; this forces the gamma rays to pass through a thicker layer of shielding before entering the house.

- Nearby trees can be removed to reduce the dose due to fallout which is on the branches and leaves. It has been suggested by the US government that a fallout shelter should not be dug close to trees for this reason.[50]

Fallout shelters in popular culture

[edit]

Fallout shelters feature prominently in the Robert A. Heinlein novel Farnham's Freehold (Heinlein built a fairly extensive shelter near his home in Colorado Springs in 1963),[51] Pulling Through by Dean Ing, A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller and Earth by David Brin.

The 1961 Twilight Zone episode "The Shelter", from a Rod Serling script, deals with the consequences of actually using a shelter. Another episode of the series called "One More Pallbearer" featured a fallout shelter owned by a millionaire. The 1985 adaption of the series had the episode "Shelter Skelter" that featured a fallout shelter.

In the Only Fools and Horses episode "The Russians are Coming", aired in 1981, Derek Trotter buys a lead fallout shelter, then decides to construct it in fear of an impending nuclear war caused by the Soviet Union.

In 1999, the film Blast from the Past was released. It is a romantic comedy film about a nuclear physicist, his wife, and son that enter a well-equipped, spacious fallout shelter during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. They do not emerge until 35 years later, in 1997. The film shows their reaction to contemporary society.

The Fallout series of computer games depicts the remains of human civilization after an immensely destructive global nuclear war; the United States of America had built underground fallout shelters known as vaults, that were advertised to protect the population against a nuclear attack, but almost all of them were in fact meant to lure subjects for long-term human experimentation.

Paranoia, a role-playing game, takes place in a city-sized fallout shelter, which has become ruled by an insane computer.

An episode of the sitcom Malcolm in the Middle features a subplot revolving around Reese and Dewey discovering a previously unknown fallout shelter in their backyard and trapping their father Hal in it, who soon becomes smitten with the shelter's 1960s decor.

The Metro 2033 book series by Russian author Dmitry Glukhovsky depicts survivors' life in the subway systems below Moscow and Saint-Petersburg after a nuclear exchange between the Russian Federation and the United States of America.

Fallout shelters are often featured on the reality television show Doomsday Preppers.[52]

The Silo series of novellas by Hugh Howey feature extensive fallout-style shelters that protect the inhabitants from an initially unknown disaster.

The 2019 US film The Tomorrow Man centers around a reclusive man whose main preoccupation is tending to his in-home fallout shelter and the conspiracy theories that could put it to use.

See also

[edit]- Abo Elementary School

- Ark Two Shelter

- Blast shelter

- Bomb shelter

- Bunker

- Bruce D. Clayton, author of Fallout Survival and Life After Doomsday

- Collective protection

- Command center

- CONELRAD

- Continuity of government

- Project Greek Island

- Vivos (underground shelter)

Nation specific:

- Central Government War Headquarters, The UKs Gov. War Headquarters at Corsham, Wiltshire.

- Diefenbunker

- HANDEL, UK's former national attack warning system

General:

Publications:

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Un abri antiatomique au fond de votre jardin". Capital.fr (in French). January 27, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ McFadden, Robert (October 27, 2017). "Robert Blakeley, Who Created a Sign of the Cold War, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "Episode 709, Story 3: N.E.A.R Device" (transcript). pbs.com. Oregon Public Broadcasting. 2009. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Civil Defense Museum-Community Shelter Tours Main Page". civildefensemuseum.com. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- ^ "FALLOUT FEVER: Civil Defense shelters dotted area cities during the Cold War – My Web Times". mywebtimes.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- ^ "DOE.gov". Archived from the original on November 7, 2009.

- ^ Bishop, Thomas (2019). ""The Struggle to Sell Survival": Family Fallout Shelters and the Limits of Consumer Citizenship". Modern American History. 2 (02): 117–138. doi:10.1017/mah.2019.8. ISSN 2515-0456.

- ^ Fortune magazine November 1961 Pages 112–115 et al

- ^ Bearman, Sophie (October 6, 2017). "Thinking the unthinkable: Don't rely on these historic fallout shelters in case of a nuclear attack". CNBC. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Allen, Jonathan (December 27, 2017). "New York City To Remove Misleading Nuclear Fallout Shelter Signs". Huffington Post. Reuters. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "Whatever Happened to the Atomitat?". A Gray Media Group, Inc. KCBD. August 6, 2002. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ McDonough, Doug (April 27, 2012). "Atomitat House used in 1966 propaganda film". Plainview Herald. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Bounds, Anna Maria (2021). Bracing for the apocalypse : an ethnographic study of New York's 'prepper' subculture (1st ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415788489. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "FOR 1995-03-15 nr 254: Forskrift om tilfluktsrom". Lovdata.no. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Pile, Tim (January 29, 2021). "Going underground: the cheapest, deepest, oldest subway systems in the world – but which is home to its own mosquito?". South China Morning Post. SCMP Publishers. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Why Sweden is home to 65,000 fallout shelters". The Local Sweden. thelocal.se. November 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e (in French) Daniele Mariani, "À chacun son bunker", Swissinfo, 23 October 2009 (page visited on 5 August 2015).

- ^ a b c "Titov bunker ARK D0 - Konjic". Visitmycountry.net. Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ "ARK – najveće atomsko sklonište bivše Jugoslavije (VIDEO) – Sandžačke novine". Sandzacke.rs. Retrieved October 21, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c "D-0 ARK Biennial (Bosnia and Herzegovina)". Biennial Foundation. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ "WONDERS OF NATURE WITH: DO KONJIC BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA". January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Zeljava Airbase". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "Underground Aircraft Dispersal Bihac Airfield, Yugoslavia 44-50N 015-47E" (PDF). National Photographic Interpretation Center. June 17, 1968. Retrieved July 28, 2022 – via nsarchive2.gwu.edu.

- ^ "Zeljava-jna_jedinice". Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ a b (in French) Catherine Frammery, "Dans les entrailles du Sonnenberg, monstrueux témoin de la Guerre froide" Archived October 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Le temps, Monday 15 August 2016 (page visited on 15 August 2015).

- ^ a b c Ball, Deborah (June 25, 2011). "Swiss Renew Push for Bomb Shelters". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 6–10. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Ravilious, Kate (September 11, 2018). "Descend Into Great Britain's Network of Secret Nuclear Bunkers". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Morris, Alec (1996). "UK Control & Reporting System from the End of WWII to ROTOR and Beyond". In Hunter, Sandy (ed.). Defending Northern Skies. Royal Air Force Historical Society. p. 104.

- ^ Grant, Matthew (2010). After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Britain, 1945–68. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-20542-0.

- ^ "T 640/384" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ Colson, Thomas (May 8, 2017). "Inside Britain's secret underground city built during the Cold War to protect the government from nuclear attack". Business Insider. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Halving-thickness for various materials". The Compass DeRose Guide to Emergency Preparedness – Hardened Shelters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 37–45. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

The 3-foot thickness of earth shown (or a 2-foot thickness of concrete) will provide an effective barrier, attenuating (absorbing) about 99.9%, of all gamma rays from fallout." "A right-angle turn, either from a vertical or horizontal entry, causes a reduction of about 90%." "...a large piece of 4-mil-thick polyethylene was placed over the mound. This waterproof material served as a "buried roof" after it was covered with more earth.

- ^ "Secret U.S. Bunkers". Lost Worlds. Episode 18. August 29, 2007. The History Channel.

- ^ a b c Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 51–56. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Foulkes, Imogen (February 10, 2007). "Swiss still braced for nuclear war". BBC News, Switzerland. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Monteyne, David. Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2011. Print.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. p. 24. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Hammes, JA (1966). "Fallout shelter survival research". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 22 (3): 154–159. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(196607)22:3<344::aid-jclp2270220330>3.0.co;2-v. PMID 5917900.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1978). The KFM, A Homemade Yet Accurate and Dependable Fallout Meter (PDF). Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2004.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 95–100. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 111–117. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ a b c Note that this image was drawn using data from the OECD report and the second edition of The Radiochemical Manual

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. p. 45. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ a b Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. p. 44. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 11–20. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ a b Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. p. 131. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ Kearny, Cresson H (1986). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. p. 39. ISBN 0-942487-01-X.

- ^ "site: Robert A. Heinlein - Archives - PM 6/52 Article". www.nitrosyncretic.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010.

- ^ "Shelter - Doomsday Preppers Article - National Geographic Channel". Archived from the original on April 1, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Rose, Kenneth D., One Nation Underground: The Fallout Shelter in American Culture, New York University Press (2004), ISBN 978-0814775233

- Readers Forum: Nuclear Fallout Shelters 50 Years Ago (Greeneville, Tennessee) by Henry Samples (1947-2024), AZER.com, in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:3 (Autumn 2006), pp. 12-13.