Novartis v. Union of India & Others

| Novartis v. Union of India | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Supreme Court of India |

| Full case name | Novartis v. Union of India & Others |

| Decided | 1 April 2013 |

| Citation | [2013] 13 S.C.R. 148 |

| Case history | |

| Prior actions | Application for patent by appellant denied by Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs on 25 January 2006; Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) partially reversed the decision by the Assistant Controller but still denied patent on 26 June 2009. |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Aftab Alam, Ranjana Prakash Desai |

| Case opinions | |

| Upheld the rejection of the patent application (1602/MAS/1998) filed by Novartis AG for Glivec in 1998 before the Indian Patent Office. | |

| Decision by | Mr. Justice Aftab Alam [1] |

Novartis v. Union of India & Others is a landmark decision by a two-judge bench of the Indian Supreme Court on the issue of whether Novartis could patent Gleevec in India, and was the culmination of a seven-year-long litigation fought by Novartis. The Supreme Court upheld the Indian patent office's rejection of the patent application.

The patent application at the centre of the case was filed by Novartis in India in 1998, after India had agreed to enter the World Trade Organization and to abide by worldwide intellectual property standards under the TRIPS agreement. As part of this agreement, India made changes to its patent law; the biggest of which was that prior to these changes, patents on products were not allowed, while afterwards they were, albeit with restrictions. These changes came into effect in 2005, so Novartis' patent application waited in a "mailbox" with others until then, under procedures that India instituted to manage the transition. India also passed certain amendments to its patent law in 2005, just before the laws came into effect, which played a key role in the rejection of the patent application.

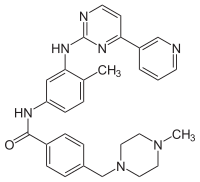

The patent application claimed the final form of Gleevec (the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate). In 1993, during the time India did not allow patents on products, Novartis had patented imatinib, with salts vaguely specified, in many countries but could not patent it in India. The key differences between the two patent applications were that the 1998 patent application specified the counterion (Gleevec is a specific salt - imatinib mesylate) while the 1993 patent application did not claim any specific salts, nor did it mention mesylate, and the 1998 patent application specified the solid form of Gleevec - the way the individual molecules are packed together into a solid when the drug itself is manufactured (this is separate from processes by which the drug itself is formulated into pills or capsules) - while the 1993 patent application did not. The solid form of imatinib mesylate in Gleevec is beta crystalline.

As provided under the TRIPS agreement, Novartis applied for Exclusive Marketing Rights (EMR) for Gleevec from the Indian Patent Office and the EMR were granted in November 2003. Novartis made use of the EMR to obtain orders against some generic manufacturers who had already launched Gleevec in India. Novartis set the price of Gleevec at USD 2666 per patient per month; generic companies were selling their versions at USD 177 to 266 per patient per month. Novartis also initiated a program to assist patients who could not afford its version of the drug, concurrent with its product launch.

When examination of Novartis' patent application began in 2005, it came under immediate attack from oppositions initiated by generic companies that were already selling Gleevec in India and by advocacy groups. The application was rejected by the patent office and by an appeal board. The key basis for the rejection was the part of Indian patent law that was created by amendment in 2005, describing the patentability of new uses for known drugs and modifications of known drugs. Section 3(d) of the amended Act, specified that such inventions are patentable only if "they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy." At one point, Novartis went to court to try to invalidate section 3(d); it argued that the provision was unconstitutionally vague and that it violated TRIPS. Novartis lost that case and did not appeal. Novartis did appeal the rejection by the patent office to India's Supreme Court, which took the case.

The Supreme Court case hinged on the interpretation of section 3(d). The Supreme Court decided that the substance that Novartis sought to patent was indeed a modification of a known drug (the raw form of imatinib, which was publicly disclosed in the 1993 patent application and in scientific articles), that Novartis did not present evidence of a difference in therapeutic efficacy between the final form of Gleevec and the raw form of imatinib, and that therefore the patent application was properly rejected by the patent office and lower courts.

Although the court ruled narrowly, and took care to note that the subject application was filed during a time of transition in Indian patent law, the decision generated widespread global news coverage and reignited debates on balancing public good with monopolistic pricing and innovation with affordability. Had Novartis won and got its patent issued, it could not have prevented generics companies in India from continuing to sell generic Gleevec, but it could have obligated them to pay a reasonable royalty under a grandfather clause included in India's patent law.

Background

[edit]History of Patent laws and pharma industry in India

[edit]As part of the Commonwealth, India inherited its intellectual property laws from Great Britain. However, after gaining independence in 1947, there was a growing consensus that to boost manufacturing, restrictive product patents must be temporarily removed.[2] In 1970, amendments to the Indian Patents Act abolished product patents but retained process patents with a reduced span of protection.

During the absence of any product patent regime, the Indian pharmaceutical industry grew at a remarkable pace, ultimately becoming a net exporter, the world's third-largest by volume, and fourteenth-largest by value.[3]

However, in the 1990s, during the Uruguay Round negotiations of the World Trade Organization (WTO), India pledged to bring its patent legislation in tune with the TRIPS mandate in a phased manner.[4] Consequently, in 1999 India allowed for transitional filing of product patent applications, with retrospective effect from 1995. Full product and process patent protection was re-introduced beginning in 2005, when all transitional regulations ended.[5]

India's patent law also contained a "grandfather clause" in section 11A, subsection (7),[6] that created "a special regime for generic versions of medicines if the initial patent application was made between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2004 and if these medicines were already on the Indian market before the 1st of January 2005.... Generics that enter into this category can stay on the Indian market even if their pharmaceutical substance is patented. However, the Indian law requires that the producers of those generics then pay a “reasonable royalty” to the patent holder."[7][8]

The case hinged on a section of the new Indian patent law dealing with whether incremental inventions would be patentable, namely Section 3(d).

The initial version read as follows: "The mere discovery of any new property or new use of a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant."[9]

This was amended twice, the last time in 2005. The final version reads as follows (amendments in italics):

"The mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant. Explanation: For the purposes of this clause, salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pureform, particle size isomers, mixtures of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives of known substance shall be considered to be the same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy."[9]

As discussed below, Novartis filed its initial patent application on imatinib (the raw material in Gleevec) in 1993, and at that time India did not confer product patents.[10] As mentioned above, in 1995 India joined the World Trade Organization and signed onto TRIPS; Switzerland joined the WTO later that same year.[11][12] Novartis filed its initial patent applications on Gleevec itself in 1997, after both India and Switzerland had joined the WTO but while both were still in transition.

Initial patent filings and product launches

[edit]In the early 1990s a number of derivatives of N-phenyl-2-pyrimidineamine were synthesized by scientists at Ciba-Geigy (now part of Novartis), one compound of which was CGP 57148 in free base form (later given the International Nonproprietary Name ‘imatinib’ by the World Health Organization (WHO)). A Swiss patent application was filed on 3 April 1992, which was then filed in the EU, the US, and other countries in March and April 1993[13][14] and in 1996 United States and European patent offices granted a patent to Novartis claiming imatinib and its derivatives, including salts thereof (but not mentioning mesylate). The patent does not specify any crystal forms of the compounds or discuss their relative advantages and disadvantages.[15][16]

On 18 July 1997, Novartis filed a new patent application in Switzerland on the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate (the mesylate salt of imatinib). The "beta crystalline form" of the molecule is a specific polymorph of imatinib mesylate; a specific way that the individual molecules pack together to form a solid. This is the actual form of the drug sold as Gleevec/Glivec; a salt (imatinib mesylate) as opposed to a free base, and the beta crystalline form as opposed to the alpha or other form.[17]: 3 On 16 July 1998, Novartis filed this patent application in India, which was given application number No.1602/MAS/1998, and on 16 July 1998, it filed a PCT, each of which claimed priority to the 1997 Swiss application.[18][19] The application showed that compared to the alpha form, the beta form had (i) more beneficial flow properties, (ii) better thermodynamic stability, (iii) lower hygroscopicity.[19] Novartis did not however provide any data showing improved efficacy (showing that this form of the drug actually worked better in treating cancer than the amorphous form of the drug they had earlier patented) - that part of Indian patent law was created in 2005, years after Novartis' initial filing. Later, during the course of prosecution, appeals, and the litigation that ensued in India, Novartis undertook studies to compare the properties of the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate (described in its new patent application), with the freebase form of imatinib (described in the older patent), and submitted them in affidavits. The studies showed that the beta crystalline form of the drug had increased bioavailability in rats.[20] A United States patent was granted in 2005.[21]

In 2001, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved imatinib mesylate in its beta crystalline form, sold by Novartis as Gleevec (U.S.)[22] or Glivec (Europe/Australia/Latin America). TIME magazine hailed Gleevec in 2001 as the "magic bullet" to cure cancer.[23][24] Both Novartis patents - on the freebase form of imatinib, and on the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate - are listed by Novartis in the FDA's Orange Book entry for Gleevec.[25]

As provided under the TRIPS agreement, Novartis applied for Exclusive Marketing Rights (EMR) for Gleevec from the Indian Patent Office and the EMR was granted in November 2003.[26] Novartis made use of the EMR to obtain orders against some generic manufacturers who had already launched Gleevec in India. Novartis set the price of Gleevec at USD 2666 per patient per month; generic companies were selling their versions at USD 177 to 266 per patient per month.[27] Novartis also initiated a program to assist patients who could not afford its version of the drug, concurrent with its product launch.[28]

Initial patent prosecution and litigation

[edit]As mentioned above, Novartis' patent application on the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate was filed in India in 1998 and put in a "mail-box" as per the TRIPS agreement.[29] The application was processed in 2005 once the law in India allowed for product patents.[30] The Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs rejected the application on 25 January 2006 as failing to satisfy requirements for novelty and non-obviousness. As the appellate board was not yet convened, Novartis filed several appeals before the Madras High Court in 2006.

Before the High Court could decide on the issue of patentability, the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) was formed and in 2007 the case was transferred before the IPAB in line with section 117G of the Indian Patent Act. The IPAB on 26 June 2009 modified the decision of the Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs stating that ingredients for grant of patent novelty and non obviousness to person skilled in the art were present in the application but rejected the application on the ground that the drug is not a new substance but an amended version of a known compound and that Novartis was unable to show any significant increase in the efficacy of the drug and it, therefore, failed the test laid down by section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act.[31][32]

Novartis mounted a separate and concurrent litigation before the Madras High Court arguing that section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act violated Article 14 of the Indian constitution because the definition of "enhanced efficacy" was too vague and left too much power in the hands of the patent examiner, and was in violation of India's obligations under the TRIPS agreement because it rendered inventions that should be patentable, unpatentable, and argued that the Court was the proper venue for hearing the claim concerning violation of TRIPS. Counsel for the Indian government argued that any violation of TRIPS belonged before the Dispute Settlement Board established by TRIPS, not before the Court, and that in any case, TRIPS allowed national laws to address the needs of its citizens; with respect to the claim that the amended law was arbitrary, counsel argued that "enhanced efficacy" is well understood in the pharmaceutical arts. In 2007, the High Court decided, agreeing with Novartis that it had the right to hear the case, and agreeing with counsel for the Indian government that the law was not vague, and that the law complied with TRIPS, and observed that section 3(d) aims to prevent evergreening and to provide easy access for Indian citizens to life saving drugs.[9] Novartis did not further challenge this order.

After IPAB rejected the patent application in 2009, Novartis appealed directly before the Supreme Court through a Special Leave Petition (SLP) under Article 136 of the Indian Constitution;[33] under normal circumstances, an appeal from IPAB should have been before one of the High Courts before it could proceed to the Supreme Court. However, the patent if granted on appeal would expire by 2018 and thus any further appeal at that stage would be pointless. Considering this urgency and the need for an authoritative decision on section 3(d) (other cases on this issue were pending before various High courts), the Supreme Court granted special leave to bypass the High Court appeals process and come directly before it.

Arguments before the Supreme Court

[edit]Novartis

[edit]The legal team of Novartis was led by ex-Solicitor General of India Gopal Subramaniam and senior advocate T. R. Andhyarujina.[34] Novartis had attempted to patent imatinib mesylate in beta crystalline form (rather than imatinib or imatinib mesylate); thus they sought to prevent extant literature on imatinib or imatininb mesylate from being considered as prior art. The thrust of the arguments by Novartis' legal team was two-fold: Firstly, that the Zimmerman patents and the journal articles published by Zimmerman et al. do not constitute prior art for the beta crystalline form as it is only one polymorph of imatinib mesylate, thereby providing the required novelty and inventive step; and secondly, that imatinib mesylate in beta crystalline form has enhanced efficacy over imatinib or imatinib mesylate to pass the test of section 3(d).

To prove novelty and inventive step it was argued that the Zimmermann patent did not teach or suggest to a person skilled in the art to select the beta crystalline form in preference to other compounds of which examples were given in the Zimmermann patent. Further, even if the beta crystalline form was selected, the Zimmermann patent did not teach a person to how to prepare that particular polymorph of the salt. Having arrived at the beta crystal form of methanesulfonic acid addition salt (mesylate salt) of imatinib, Novartis contended that the inventors had to further research to be able to ensure that particular salt form of imatinib was suitable for administration in a solid oral dosage form. Hence, the coming into being of the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate from the free base of imatinib was the result of an invention that involved technical advance as compared to the existing knowledge and brought into existence a new substance. Research was required to define and optimise the process parameters to selectively prepare the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate. As the Zimmermann patent contains no mention of polymorphism or crystalline structure, the relevant crystalline form that was synthesized needed to be invented. There was no way of predicting that the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate would possess the characteristics that would make it orally administrable to humans without going through the inventive steps.[35]

To prove that the beta crystalline form enhanced efficacy over other, it was stated that beta crystalline form has (i) more beneficial flow properties, (ii) better thermodynamic stability, (iii) lower hygroscopicity, and (iv) increased bioavailability.[20]

Respondents

[edit]There were seven named respondents who were represented before the court along with two Intervenor/Amicus. The respondents were led by Additional Solicitor-General of India Paras Kuhad.[34]

Various arguments were brought before the court but primarily focussed on proving that imatinib mesylate in beta crystalline form was neither novel nor non-obvious due to publications about imatinib mesylate in Cancer Research and Nature in 1996, disclosures in Zimmerman patents, disclosures to FDA and finally that efficacy as referred to in section 3(d) should be interpreted as therapeutic efficacy and not merely a physical efficacy.[36]

The respondents quoted extensively from Doha Declaration on the TRIPS agreement and public health, excerpts from parliamentary debates, petitions from NGOs, WHO, etc. to highlight the public policy dimension of arguments in regards to easy affordability and availability of life saving drugs.

Supreme Court decision

[edit]Supreme Court decided the matter de novo looking into matters of both fact and law.

The court first analysed the question of prior art by looking into Zimmerman patent and the related academic publications. It was clear from the Zimmerman patent that imatinib mesylate itself was not new and did not qualify the test of invention as laid down in section 2(1)(j) and section 2(1)(ja) of the Patents Act, 1970.[37] The court then examined the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate and wrote that it, "for the sake of argument, may be accepted to be new, in the sense that it is not known from the Zimmermann patent. (Whether or not it involves an “inventive step” is another matter, and there is no need to go into that aspect of the matter now). Now, the beta crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate being a pharmaceutical substance and moreover a polymorph of Imatinib Mesylate, it directly runs into section 3(d) of the Act with the explanation appended to the provision".[38]

In applying 3(d) of the Act, the Court decided to interpret "efficacy" as "therapeutic efficacy" because the subject matter of the patent is a compound of medicinal value. Court acknowledged that physical efficacy of imatinib mesylate in beta crystalline form was enhanced in comparison to other forms and that the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate had 30 per cent increased bioavailability as compared to imatinib in free base form;[39] however, as no material had been offered to indicate that the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate would produce an enhanced or superior efficacy (therapeutic) on molecular basis than what could be achieved with imatinib free base in vivo animal model, the court opined that the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate, did not qualify the test of Section 3(d).[40][41]

Thus in effect, the Court upheld the view that under Indian Patent Act for grant of pharmaceutical patents apart from proving the traditional tests of novelty, inventive step and application, there is a new test of enhanced therapeutic efficacy for claims that cover incremental changes to existing drugs.[42]

The Court took pains to point out that the subject patent application was filed during a time of transition in Indian patent law, especially with regard to striking Section 5, which had barred product patents and adding section 3(d), for which there was no case law yet.[43] The Court also took care to state the decision was intended to be narrow: "We have held that the subject product, the beta crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate, does not qualify the test of Section 3(d) of the Act but that is not to say that Section 3(d) bars patent protection for all incremental inventions of chemical and pharmaceutical substances. It will be a grave mistake to read this judgment to mean that section 3(d) was amended with the intent to undo the fundamental change brought in the patent regime by deletion of section 5 from the Parent Act. That is not said in this judgment."[44]

Reception

[edit]The decision received extensive coverage from Indian and international media.[28][45][46][47][48]

It reignited debates on balancing public good with monopolistic pricing and innovation with affordability.[49][50][51]

Several commenters, including Novartis, noted that a decision either way would not have affected the ability of generics companies in India to continue selling generic Gleevec. The new patent law India adopted in 2005 contains a grandfather clause that allows generic copies of drugs launched before 2005, which includes Gleevec, to continue to be sold, albeit with payment of a reasonable royalty to Novartis.[8][52] Other commenters noted that the case was unique with respect to its timing and the importance of the drug, and that large generalizations should not be taken from it. "As a case study, Glivec is peculiar and unlikely to be representative going forward. Had it been invented a few years later (or TRIPS implemented a few years earlier), Glivec likely would be patented in India, even under 3(d) standards. Newly discovered compounds are likely to receive basic patents and to be less vulnerable to 3(d) rejections."[53] Prashant Reddy, author of the Spicy IP blog and postgraduate student at Stanford University Law School, was quoted in Nature Drug Discovery as saying: "It was a very limited ruling in most aspects and very fact-specific. Although the Court has interpreted efficacy to mean only therapeutic efficacy, it has left the exact scope of therapeutic efficacy to be defined in future cases....Most importantly, the Court made the nuanced distinction between the rent-seeking practice of evergreening and the beneficial practice of incremental innovation, and has clarified that Indian patent law forbids only the former."[54][55]

There were however strong negative and positive reactions.

Support

[edit]The judgement garnered widespread support from international organisations and advocacy groups like Médecins Sans Frontières,[56] WHO, etc. who welcomed the decision against evergreening of pharmaceutical patents.

Most news item contrasted the huge price difference between patented Gleevec of Novartis and the generic versions of Cipla and other generic companies.[57][58] Some commentators have stated that this strict patent requirement would actually enhance innovation as the pharmaceutical companies would have to invest more in R&D to come up with new cures rather than repackage known compounds.[59] Others have suggested that exclusions under section 3(d) present the hard cases that lie at the margins of the patent system due to the eternally unsettled nature of the definition of the term 'invention'.[60] Several patent law experts have also pointed out that stringent conditions for patentability are followed in many jurisdictions around the world, and there is no reason India should not follow the same standards, given the extent of poverty and lack of availability of affordable medicines in the country.[61]

Opposition

[edit]Ranjit Shahani, vice-chairman and managing director of Novartis India Ltd is quoted as saying "This ruling is a setback for patients that will hinder medical progress for diseases without effective treatment options."[62] He also said that companies like Novartis would invest less money in research in India as a result of the ruling.[46] Novartis also emphasized that it continues to be committed to access to its drugs; according to Novartis, by 2013, "95% of patients in India—roughly 16,000 people—receive Glivec free of charge... and it has provided more than $1.7 billion worth of Glivec to Indian patients in its support program since it was started...."[28] The New York Times quoted Chip Davis, the executive vice president of advocacy at the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the industry trade group: "It really is in our view another example of what I would characterize as a deteriorating innovation environment in India. The Indian government and the Indian courts have come down on the side that doesn’t recognize the value of innovation and the value of strong intellectual property, which we believe is essential."[46]

References

[edit]- ^ "Novartis v. Union Of India & Ors on 1 April 2013" (PDF).

- ^ Rawat, Balwant (31 October 2009). "Patenting Landscape in India 2009". doi:10.2139/ssrn.1502421. S2CID 109250422. SSRN 1502421.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Pharma to topple IT as big paymaster". The Economic Times. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ "History of Patent Law in India".

- ^ Chaudhry, Sharmendra (8 February 2011). "Product v. Process Patent in India". doi:10.2139/ssrn.1758064. S2CID 111193911. SSRN 1758064.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Controller General of Patents Designs and Trade Marks, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Ministry of Commerce and Industry The Patents Act 1970 (incorporating all amendments till 26-01-2013)

- ^ Erklärung von Bern. 8 May 2007 Short questions and answers about the court case initiated by Novartis in India Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kevin Grogan for PharmaTimes. 27 February 2012 Novartis explains stance over India patent law challenge Archived 2014-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "W.P. No.24759 of 2006". Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Finally, the patients prevail, Sarah Hiddlestone, The Hindu, 7 April 2013

- ^ Switzerland page at WTO

- ^ Note: Further complicating matters, India's 1993 notification to the WTO indicating that it would join, included a list of countries whose priorities dates it would recognize for patenting, and Switzerland was not on the list as it was not a member of the WTO at that time.(Sudhir Ahuja, D P Ahuja & Co, Calcutta, India. India Decides to Join the Paris Convention and Ratify the Patent Cooperation Treaty. So What? Patent World Issue #106, October 1998). Additionally the EPO was not mentioned in the notification from India; it was not until 2003 that EPO became officially recognized by India, fully normalizing patent reciprocity between India and Europe. (G 0002/02 (Priorities from India/ASTRAZENECA) of 26.4.2004)

- ^ US Patent Application No. 08/042,322). This application was abandoned and another continuation-in-part application was then filed on 28 April 1994 which matured into (US Patent 5,521,184).

- ^ See here for worldwide filings]

- ^ US Patent 5,521,184

- ^ EP0564409

- ^ Staff, European Medicines Agency, 2004. EMEA Scientific Discussion of Glivec

- ^ Note: The Indian patent application does not appear to be publicly available. However according to the decision of the IPAB on 26 June 2009 (page 27) discussed below, "The Appellant’s application under the PCT was substantially on the same invention as had been made in India."

- ^ a b Published PCT application WO1999003854

- ^ a b "Novartis v UoI, para 168" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ US Patent 6,894,051

- ^ Investigational New Drug Application (IND # 55,666) for Gleevec was filed on 9 April 1998 and on 27 February 2001, the original New Drug Application (FDA Drug Approval Package for Gleevec NDA # 21-335) was filed before the US Food and Drug Administration for imatinib mesylate for the treatment of patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

- ^ Closing In On Cancer by Alice Park, TIME Magazine, 21 May 2001

- ^ Novartis' Gleevec Cancer "Magic Bullet" Extends Life In GIST Patients, 6 June 2011

- ^ FDA Orange Book; Patent and Exclusivity Search Results from query on Appl No 021588 Product 001 in the OB_Rx list.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, para 8-9" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Staff, LawyersCollective. 6 September 2011 Novartis case: background and update – Supreme Court of India to recommence hearing Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c R. Jai Krishna and Jeanne Whalen for the Wall Street Journal. 1 April 2013 Novartis Loses Glivec Patent Battle in India

- ^ Application No.1602/MAS/1998

- ^ The patent application attracted five pre-grant oppositions by M/s. Cancer Patients Aid Association, NATCO Pharma Ltd., CIPLA Ltd., Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. and Hetro Drugs Ltd. The Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs heard all the parties on 15 December 2005, as provided under rule 55 of the Patent Rules, 2003.

- ^ Intellectual Property Appellate Board decision dated 26 June 2009, p 149

- ^ Shamnad Basheer for Spicy IP 11 March 2006 First Mailbox Opposition (Gleevec) Decided in India

- ^ Article 136 of the Indian Constitution

- ^ a b "Supreme Court rejects Novartis patent plea for cancer drug Glivec". Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, para 105-108" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ The Novartis Patent Intervention by Prof. Shamnad Basheer

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 157" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 158" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 187, 188" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 189, 191" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Novartis A.G. v. UOI & Ors. – Hon’ble Justice Aftab Alam’s Swansong, Rudrajyoti Nath Ray, RDA, 8 April 2013

- ^ Novartis and Health - An analysis, Rajeev Dhavan, 11 April 2013

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 24-25" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Novartis v UoI, Para 191" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Rama Lakshmi for the Washington Post 1 April 2013 India rejects Novartis drug patent

- ^ a b c Gardiner Harris and Katie Thomas for the New York Times. 1 April 2013 Published: 1 April 2013 Top court in India rejects Novartis drug patent

- ^ Sarah Boseley for The Guardian, 1 April 2013 Novartis patent ruling a victory in battle for affordable medicines

- ^ Staff, BBC. 2 April 2013 Novartis case: Media hail 'key victory' for India

- ^ "How the Indian judgment will reverberate across the world". 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Patented drugs must be priced smartly". Archived from the original on 5 April 2013.

- ^ Patent with a purpose, Prof. Shamnad Basheer, Indian Express, 3 April 2013

- ^ M Allirajan, TNN 4 April 2013 SC decision on Glivec is negative credit for branded drug firms: Moody’s

- ^ Sampat BN et al. Challenges to India's Pharmaceutical Patent Laws Science 27 July 2012: Vol. 337 no. 6093 pp. 414-415

- ^ Charlotte Harrison Patent watch Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 12, 336–337 (2013)

- ^ "Supreme Court rejects bid by Novartis to patent Glivec". 12 June 2023.

- ^ Major victory on affordable drugs

- ^ Salve on cheaper medicine Patent blow to Big Pharma, The Telegraph

- ^ "Drug price cut signal after court victory". Archived from the original on 21 October 2013.

- ^ Why Novartis case will help innovation, Achal Prabhala and Sudhir Krishnaswamy, The Hindu, 15 April 2013

- ^ A New Template for Pharma Research, Yogesh Pai, The Hindu Business Line, 11 April 2013

- ^ Nothing wrong with setting high standards of patentability, Srividhya Ragavan and Aju John, myLaw.net, 10 May 2013

- ^ Shift in Novartis Strategy, The Telegraph