Nosseni epitaph

The Nosseni epitaph is the epitaph for the Swiss sculptor Giovanni Maria Nosseni, parts of which have been preserved. It was made in 1616 before Nosseni's death and stood in the Sophienkirche until it was severely damaged during the air raids on Dresden in 1945. Parts of the epitaph are currently on public display at various locations in the city of Dresden.

History

[edit]Around 1600, Nosseni was regarded as the "most important artistic personality for Dresden".[1] He was a teacher for numerous later important Dresden sculptors and had popularized the art of Italian Renaissance sculpture in the Electorate of Saxony since settling in Dresden in 1575. He enjoyed a high reputation as a Saxon court sculptor and foreign artist. He designed works and supervised their execution, but rarely sculpted them himself.

As a court sculptor, Nosseni could afford to be buried in the Church of St. Sophia, which was designed as a funeral church and was only possible for the upper classes of the city due to the burial costs of 50 thalers.[2] Nosseni was also associated with St. Sophia's Church, as he had created the Main Altar of the Church in 1606 after being commissioned by Electress Sophie.

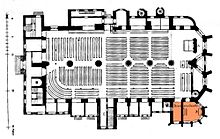

Four years before his death, Nosseni had his own funerary monument erected. It was designed to stand on one of the octagonal pillars of St. Sophia's Church,[3] and therefore had a broken ground plan forming three sides of an octagon. Nosseni's most important assistant Sebastian Walther and Zacharias Hegewald are considered to be the sculptors of the epitaph.[4]

The epitaph was placed on the westernmost fifth pillar of the church after Nosseni's death in 1620. When the interior of St. Sophia's Church was rebuilt in 1875, the epitaph was "inconveniently moved to the Busmannkapelle"[5] and placed it in a corner. By this time, the structure of the epitaph with a depiction of the Last Judgement had already been lost. Instead, the epitaph was finished off with a cranked entablature. It was only during a second interior renovation of the church in 1910 that the epitaph was "reinstalled in a preferred position in the church worthy of the master";[6] it was now located on the first pillar directly next to the Nosseni altar.

In 1910, the epitaph consisted of two side reliefs with consoles and crowning as well as a central niche in front of which stood the sculpture of the Ecce homo. At the beginning of World War II, the sculpture was stored in the cellar of the Dresdner Frauenkirche, which was considered bombproof. While the epitaph was severely damaged in the destruction of St. Sophia's Church and the partially preserved reliefs are now in the Dresden City Museum, the Ecce homo was considered a war loss. It was only during the demolition of the Frauenkirche on April 7, 1994 that the sculpture was rediscovered in the collapsed western main vault of the church. Although the figure was broken, its details were so well preserved that it could be restored.[7] It has been located in the Dresdner Kreuzkirche since 1998.[8] Further fragments of the epitaph, including pieces of the coronation, are stored in the Saxon State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in the Ständehaus in Dresden.The design of the Busmann Chapel Memorial (today: DenkRaum Sophienkirche) by Gustavs and Lungwitz, a memorial for the Sophienkirche, also provided for the reconstruction of the Nosseni epitaph. It was to be erected centrally in the stylized choir of the chapel on the site of the former altar. The plan was to use the space of the chapel for events and devotions, with visitors generally looking at the Ecce homo of the epitaph, which "stands for the suffering of the city, but also promises redemption".[9] A reconstruction of the epitaph was not finally realized. The Ecce Homo of the epitaph has been in the DenkRaum Sophienkirche since 2020.

Description

[edit]Left side

[edit]

On the left side of the Ecce homo was a kneeling male figure in alabaster relief, depicting Nosseni himself. The bearded man with short, sparse hair wears clothing typical of the period and kneels with his left knee on a cushion, while his right knee is slightly raised. A cloak is draped over his shoulders and his chest is adorned with two foam coins. The fingers on both the right and left hand were already broken off around 1900; the left hand originally held a sword, but this was also missing around 1900.

The inscription gave the dates of Nosseni's life and his activities:

JOHANNES MARIA NOSENIUS / Luganensis Italus natus / Aō. C. MDXLV. M. Maii / Sereniss. Augusti. Christi / ani primi. Christiani II. et / Johannis Georgi electorū / Saxon. architectus. Fragi / litatis humanæ memor in / spem beatae resurrectionis / vivens sibi e tribus uxoribus.

— Original zit. nach Gurlitt, 1900 [10]

In 1912 Robert Bruck found it remarkable that Nosseni was named in the inscription as an architect ("architectus") but not as a sculptor.[11] Only the relief from the left side of the epitaph has survived, with parts of the right foot missing. The bench with cushion on which the figure was kneeling has also not survived.

Nosseni's relief is considered to be "a masterpiece of distinguished character".[12]

Center page

[edit]

The central side showed a flat niche, which was framed by Corinthian marble columns. In front of the niche, on a four-sided plinth, stood the approximately 165 cm high stone sculpture, which was designated Ecce homo on the plinth. Around 1900, the sculpture had already been painted over with gray oil paint.

Christ is depicted with a crown of thorns, his left hip is pushed out from the viewer and his torso is tilted to the right. The head - "the facial expression is pained, but without distortion"[10] - is turned to the left and the hands are crossed to the right. A robe covers the back and loin. The central sculpture is considered to be "one of the rare free-standing statues of monumental format created by Germans at the time"[13] and shows clear, albeit exaggerated, echoes of Michelangelo's sculpture The Risen Christ in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome.[14]

The pedestal on which the Ecce homo stood contained Bible verses on three sides.[10]

|

Left |

Center |

Right |

Right side

[edit]

On the right-hand side of the Ecce homo, a relief depicts Nosseni's three wives in a kneeling position. On the left, the first wife Elisabeth Unruh, who died in 1579, is depicted in profile. She wears a death shroud and looks upwards, her hands folded in prayer.Nosseni's second wife, Christiane Hanitsch, who died in 1606, is depicted in the center. She is depicted as younger than Elisabeth and is looking forward. Her right hand is open, while her left hand holds a prayer book. The figure is also wearing a shroud and appears to be engrossed in a conversation with the woman behind her.[13]

The woman depicted on the right is Nosseni's third wife, Anna Maria von Rehen, whom he had married in 1609 and who survived him. Like Christiane, she is depicted as rather youthful, but is not wearing a death veil, but a ruff, a hood and a fur coat with a chain of grace.All three women are kneeling on cushions and were composed next to each other in a confined space. The alabaster relief is therefore considered a "less successful group", also with regard to Nosseni's relief.[13]

The inscription below the relief gave the dates of the wives' lives:

Elisabethæ . . . . na. XVII. Jul. / Aō. C. M.D.LVII. defunctæ / XIV. Febru. Aō. C MDXCI / Christinæ. na. XV. Decem. / Aō. C. M.D.LXXV denatae / XXX. Nov. Aō. C MDCVI / Annae Maria superstitina / III. Febru. Aō. C MDLXXXIX / Hoc / Monumen. poni cura / vit M. Sep. Aō. C. M.DC.XVI.

— Original zit. nach Gurlitt, 1900 [5]

The fingers of the left and middle female figure were already missing in 1900. The relief was preserved, but the base with the inscription was destroyed.

Executing sculptors

[edit]It is difficult to precisely attribute individual parts of the epitaph to the sculptors who executed it. As early as the late 17th century, "the famous sculptors Walther and Hegewald" were named as the executing sculptors.[13] Her work on the epitaph was partly based on Gottlob Oettrich's Ecce homo,[15] in other cases referring to the entire epitaph.

In 1900, Cornelius Gurlitt referred to Gottlob Oettrich and, like him, attributed the Ecce homo to Sebastian Walther and Zacharias Hegewald. Nosseni's relief on the side, on the other hand, is "of extraordinary mastery and can probably be attributed to Nosseni himself."[10]

However, Bruck pointed out in 1912 that Nosseni "did not create his own sculptural commissions, but commissioned other artists or assistants from his workshop to execute his designs".[16] He also recognizes "that two different hands worked on the work, [...] for the Ecce homo differs sharply in style from the alabaster reliefs on the two sides."[4] By comparing styles, he attributed the Ecce homo to Zacharias Hegewald and the alabaster reliefs on the sides to Sebastian Walther.[17]

Walter Hentschel suspected that Sebastian Walther did most of the work on the epitaph, as Hegewald was only 20 years old in 1616 and thus comparatively inexperienced in the craft.[13]

Literature

[edit]- Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 49–54.

- Cornelius Gurlitt: Beschreibende Darstellung der älteren Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler des Königreichs Sachsen. Band 21: Stadt Dresden, Teil 1. C. C. Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 102–104.

- Walter Hentschel: Dresdner Bildhauer des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts. Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar 1966, p. 77.

References

[edit]- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 45.

- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 15.

- ^ Gottlob Oettrich: Richtiges Verzeichniß derer Verstorbenen, nebst ihren Monumenten, und Epitaphien, welche inwendig in hiesiger Kirchen zu St. Sophien ihre Ruhe gefunden. Dreßden 1710/1711, p. 117.

- ^ a b Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 51.

- ^ a b Cornelius Gurlitt: Beschreibende Darstellung der älteren Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler des Königreichs Sachsen. Band 21: Stadt Dresden, Teil 1. C. C. Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 104.

- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 38.

- ^ Wolfram Jäger: Bericht über die archäologische Enttrümmerung 1993/94. In: Gesellschaft zur Förderung des Wiederaufbaus der Frauenkirche Dresden e. V. (Hrsg.): Die Dresdner Frauenkirche. Jahrbuch 1995. Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar 1995, p. 19–20.

- ^ Bild der Skulptur „Ecce homo“ in der Dresdner Kreuzkirche (Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive)

- ^ Gerhard Glaser: Die Gedenkstätte Sophienkirche. Ein Ort der Trauer, ein Ort gegen das Vergessen. In: Heinrich Magirius, Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Sophienkirche (Hrsg.): Die Dresdner Frauenkirche. Jahrbuch zu ihrer Geschichte und Gegenwart. Band 13. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2009, p. 198–200.

- ^ a b c d Cornelius Gurlitt: Beschreibende Darstellung der älteren Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler des Königreichs Sachsen. Band 21: Stadt Dresden, Teil 1. C. C. Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 102.

- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 50.

- ^ Georg Dehio: Handbuch der deutschen Kunstdenkmäler. Band 1: Mitteldeutschland. Wasmuth, Berlin 1914, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e Walter Hentschel: Dresdner Bildhauer des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts. Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar 1966, p. 77.

- ^ Georg Dehio: Handbuch der deutschen Kunstdenkmäler. Band 1: Mitteldeutschland. Wasmuth, Berlin 1914, p. 81f.

- ^ Vgl. Gottlob Oettrich: Richtiges Verzeichniß derer Verstorbenen, nebst ihren Monumenten, und Epitaphien, welche inwendig in hiesiger Kirchen zu St. Sophien ihre Ruhe gefunden. Dreßden 1710/1711.

- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 49.

- ^ Robert Bruck: Die Sophienkirche in Dresden. Ihre Geschichte und ihre Kunstschätze. Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 52.