Bangladeshi diaspora

Parts of this article (those related to documentation) need to be updated. (August 2020) |

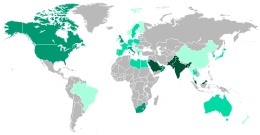

The Bangladeshi diaspora (Bengali: প্রবাসী বাংলাদেশী) are people of Bangladeshi birth, descent or origin who live outside of Bangladesh. First-generation migrants may have moved abroad from Bangladesh for various reasons including better living conditions, to escape poverty, to support their financial condition, or to send money back to families there. The Ministry of Expatriates' Welfare and Overseas Employment estimates there are almost 7.5 million Bangladeshis living abroad, the fourth highest among the top 176 countries of origin for international migrants.[citation needed] Annual remittances transferred to Bangladesh were almost $23 billion in 2023, the seventh highest in the world[43] and the third highest in South Asia.[44]

The largest Bangladeshi diaspora population is in Saudi Arabia. There are also significant migrant communities in various Arab states of the Persian Gulf, particularly the United Arab Emirates and Oman, where Bangladeshis are mainly classified as foreign workers. The United Kingdom is home to the largest Bangladeshi community in Europe.[45] British Bangladeshis are mainly concentrated in London boroughs such as (Tower Hamlets and Newham); the migration to Britain is mainly attributed with chain migration from the Sylhet Division. In addition to the UK and the Middle East, Bangladeshis also have a significant presence in the United States.[46] Other countries where there are significant Bangladeshi communities include Malaysia, South Africa, Singapore, Italy, Canada, and Australia. The majority of the Bangladeshi diaspora are Muslim, with a significant Hindu minority.

Bangladeshi diaspora movements and settlements abroad have divergent histories and challenges, with the diaspora in the Gulf Cooperation Council states focused on ensuring continuous labor migration flows and reducing labor-related abuses, while in the US and UK, a major challenge is the growing intergenerational divides.[47]

South Asia

[edit]Maldives

[edit]According to the Maldivian foreign ministry; some 50,000 Bangladeshi were working in there in 2011, a nation of only around 400,000 people, with a third having no valid documents or registration.[48]

Pakistan

[edit]Middle East

[edit]Bangladeshis in the Middle East form the largest part of the worldwide Bangladeshi diaspora. Between 2.3 million and 2.9 million live within the Middle East.

More than two million are in Saudi Arabia.[49] The United Arab Emirates is home to 706,000.[50] Oman has about 680,242 Bangladeshis as of 2018.[51] There is a Bangladeshi school in the city of Muscat, in Oman, called Bangladesh School Muscat.[citation needed] Qatar has about 400,000 Bangladeshis as of 2019.[52] There is a Bangladeshi school in Doha called Bangladesh MHM School & College. Bangladeshis in Qatar make more than 14% of the Qatar population.[citation needed] Kuwait has about 350,000 Bangladeshis as of 2020.[53] Bahrain has about 180,000 Bangladeshis as of 2017.[54]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]The introduction of Islam to the Bengali people has generated a connection to the Arabian Peninsula, as Muslims are required to visit the land once in their lifetime to complete the Hajj pilgrimage. Several Bengali sultans funded Islamic institutions in the Hejaz, which popularly became known by the Arabs as Bangali Madaris. It is unknown when Bengalis began settling in Arab lands though an early example is that of Haji Shariatullah's teacher Mawlana Murad, who was permanently residing in the city of Mecca in the early 1800s.[55] There are about three major Bangladeshi schools in Saudi Arabia in Riyadh, Jeddah and Dammam.[citation needed]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]There are 706,000 Bangladeshis residing in the United Arab Emirates as of 2020.[50] There is one Bangladeshi school in UAE called Shaikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Bangladesh Islamia School in Abu Dhabi. Bangladeshis make up around 7% of the UAE population and are 4th largest community in the UAE.[citation needed]

East and Southeast Asia

[edit]Malaysia

[edit]The Bangladeshi population in Malaysia is 400,000 as of 2023.

South Korea

[edit]In South Korea, there are more than 12,678 Bangladeshi foreign workers in the country as of 2013.[56] A few of them include illegal immigrants. The 2009 Korean film Bandhobi, directed by Sin Dong-il, depicts a Bangladeshi migrant in South Korea.[57]

Japan

[edit]Bangladeshis in Japan (在日バングラデシュ人, Zainichi Banguradeshujin) form one of the smaller populations of foreigners in Japan. As of 2010, Japan's Ministry of Justice recorded 10,175 Bangladeshi nationals among the total population of registered foreigners in Japan.[58]

Western world

[edit]United States

[edit]The census in 2000 found up to 95,300 were born in Bangladesh. It was until the 1990s when Bangladeshis, many from Dhaka, Chittagong, and Sylhet, started to move to the United States, and settled in urban areas such as New York, Paterson in New Jersey, Philadelphia, Atlantic City, New Jersey, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles. Although recent findings claim that Bangladeshis started arriving during the late 19th centuries from the southern part of current Bangladesh. In some parts of Queens and Manhattan in New York City, there are Bangladeshi restaurant owners of Indian restaurants, Pakistani restaurants, and Bangladeshi restaurants.[59][60] The Baishakhi Mela celebration of the Bengali New Year is also held by the Bangladeshi American communities in New York, Paterson, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Atlantic Cityand other cities annually. The street of 3rd Street, Los Angeles has a large history of Bangladeshis and has officially been dubbed as "Little Bangladesh". In "Little Bangladesh", Bengali Muslims arrange Chaand Raat celebrations by performing classic, lively Bengali folk songs with the crowds singing along and selling Fuskas (a Bangladeshi street snack of fried semolina dough filled with spicy chickpeas, potatoes and toppings).[61] However, some Bangladeshis residing in New York have settled in newer areas, such as Hamtramck, Michigan, Buffalo, New York, Paterson, New Jersey, and many other nearby states due to lower living costs and better job opportunities. Many Bangladeshis in New York City are often Taxi Drivers, Fast-Food Chain Workers, Restaurant Workers, software developer, computer scientists, medical doctors, attorneys, accountants, business owners, company CEO etc. In Atlantic City many work in casinos.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2018 American Community Survey, there were 213,372 people of Bangladeshi origin living in the US.[46]

Canada

[edit]Bangladeshi Canadian refers to a person of Bangladeshi background born in Canada or a Bangladeshi that has migrated to Canada. Before 1971 about 150 Bengali people came to Canada as East Pakistani. The main influx of migration of Bangladeshis started in the early 1980s. Back in 1988, about 700 Bangladeshi families lived in Toronto, though about another 900 families were living in Montreal. Now, Toronto has a sizeable Bangladeshi community significantly larger than Montreal's, with over 50,000 in the city proper and over 65,000 in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto's eastern boroughs of East York and Scarborough on Danforth Avenue have a sizable Bangladeshi population. The area around Danforth east and west of Victoria Park Avenue has many Bangladeshi stores and restaurants. The Crescent Town neighbourhood just north of Danforth, which consists of many high-rise apartment buildings, has primarily a Bengali population. In 2019, a petition was started to rename Danforth Avenue, or at least a part of it, to Bangladesh Avenue. This request was made to honour the large Bangladeshi community that was established there. In July 2023, the City of Toronto officially designated Danforth Avenue, between Pharmacy Avenue and Main Street as "Banglatown". Under the Investor Category, about 100 families moved to Canada since 2015.

Australia

[edit]Bangladeshis in Australia are one of the smallest immigrant communities living in Australia.[citation needed] There are around 41,000 Bangladeshis in Australia.[62] The largest Bangladeshi communities are mainly present in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, with large concentrations in the cities of Sydney and Melbourne.[citation needed]

Brazil

[edit]Bangladeshis started arriving in Brazil in the 1980s. There are around 2,000 people of Bangladeshi origin in Brazil with most of them living in São Paulo as of 2021. Bangladeshi nationals, who live in Brazil, mainly depend on fabrics, clothing and garment trade. But many are service holders and some work in poultry farms, grocery shops and restaurants.[63]

Europe

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]

Earliest records of Bengalis in the European continent date back to the reign of King George III of England during the 18th century. One such example is of James Achilles Kirkpatrick's hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) who was said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.[64] Mass migration started since the days of the British Raj, where lascars from Sylhet were often sent to the United Kingdom. Some of these lascars lived in the United Kingdom in port cities, and even married British women. Since then, mass migration has occurred, specifically from Sylhet. Today, the British Bangladeshis are a naturalised community in the United Kingdom, running 90% of all South Asian cuisine restaurants and having established numerous ethnic enclaves across the country – most prominent of which is Banglatown in East London.[65]

The street of Brick Lane in East London, has a large history of Bangladeshis and has officially been dubbed as "Banglatown", and has hundreds of "Indian" restaurants nearly all owned by Sylheti Bangladeshis. Many British Bangladeshis have made their presence in the UK, often becoming doctors, engineers, and lawyers, but also many have become politicians for the Labour party, such as Rushanara Ali, and Tulip Siddiq, as well as London Borough Mayors, such as Lutfur Rahman and Nasim Ali.

Italy

[edit]Bangladeshis are one of the largest immigrant populations in Italy.[66] As of 2022, there were 150,692 Bangladeshis in Italy.[67] Most of the Bangladeshis in Italy are based in Lazio, Lombardy and Veneto with large concentrations in Rome, Milan and Venice.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- "Bangladesh 6th largest migrant sending country". The Daily Star. 2 December 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Bangladeshi Diaspora". 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia 2022 Census" (PDF). General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Migration Profile – UAE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Ethnic group, England and Wales: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion - Chart data". Scotland's Census. National Records of Scotland. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024. Alternative URL 'Search data by location' > 'All of Scotland' > 'Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion' > 'Ethnic Group'

- ^ "Census 2021 Ethnic group - full detail MS-B02". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Bangladeshis top expatriate force in Oman". Gulf News. 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality - 2019 report". Priya Dsouza. 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshi Workers: Around 2 lakh may have to leave Kuwait". The Daily Star. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "US Census Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Over 400 Bangladeshis murdered in South Africa in 4yrs". Dhaka Tribune. AFP. 1 October 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Bangladeshi Migrants in Malaysia

- ^ "Economic crisis in Lebanon: job losses, low pay hit expats". The Daily Star. 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "90% drop in illegal Bangladeshi expats in Bahrain". Zawya. Gulf Daily News. 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Help at hand for Bangladeshi workers in Middle East". Arab News. 11 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshis in Singapore". The Straits Times. 15 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "La Comunitá Bangladese in Italia" (PDF). Ministry of Labour and Social Policies (in Italian). 2019.

- ^ "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". 26 October 2022.

- ^ Ibraheem, Imon (9 February 2021), "Maldives to recruit workers from Bangladesh", Dhaka Tribune, retrieved 28 May 2021,

The president of the Maldives has already declared that all the workers --- including foreigners, will get free vaccination in his country --- "We'll send some nurses to help carry out vaccination in the Maldives particularly for the large Bangladeshi community staying there," he said---Some 80,000 Bangladeshi expatriates are currently working in the Maldives.

- ^ a b c Monem, Mobasser (July 2018). "Engagement of Nonresident Bangladshis in National Development: Strategies, Challenges and Way Forward" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Monem, Mobasser (November 2017). "Engagement of Non-resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) in National Development: Strategies, Challenges and Way Forward" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme.

- ^ Mahmud, Jamil (3 April 2020). "Bangladeshis in Spain suffering". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "2021 People in Australia who were born in Bangladesh, Census Country of birth QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".

- ^ Mahbub, Mehdi (16 May 2016). "Brunei, a destination for Bangladeshi migrant workers". The Financial Express (Bangladesh). Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshi immigrants now at forefront at Portugal's Lisbon neighbourhood". The Daily Star. 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Momen urges Portugal to open mission in Dhaka | News Flash". BSS.

- ^ Portugal, Rádio e Televisão de (1 March 2018). ""Bangla em Lisboa". Surpreendente retrato de uma comunidade rendida a Portugal". "Bangla em Lisboa". Surpreendente retrato de uma comunidade rendida a Portugal.

- ^ "Portugal: Bangladesh's next big EU trade partner?".

- ^ "Bangladeshi workers facing difficulty in sending money from Mauritius". The Daily Star. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "令和5年6月末現在における在留外国人数について | 出入国在留管理庁". www.moj.go.jp.

- ^ Mahmud, Ezaz (17 April 2021). "South Korea bans issuing visas for Bangladeshis". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Fighting in Libya: Condition of thousands of Bangladeshis gets worse, says Bangladesh ambassador". Dhaka Tribune. 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Poland is cocking up migration in a very European way". The Economist. 22 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Stay in safer places". 17 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Étrangers – Immigrés : pays de naissance et nationalités détaillés". Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Sweden: Asian immigrants by country of birth 2020". Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Finland – A country of curiosity". The Daily Star. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Livelihoods of Bangladeshis at stake in Covid-19 hit Brazil". 19 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshi Migrants in Europe 2020" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "2018 Census ethnic group summaries | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz.

- ^ Mannan, Kazi Abdul; Kozlov, V.V. (1995). "Socio-economic life style of Bangladeshi man married to Russian girl: An analysis of migration and integration perspective". doi:10.2139/ssrn.3648152. SSRN 3648152.

- ^ "Bangladesh 7th highest remittance recipient: World Bank". The Daily Star. 13 May 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Bangladesh's remittance inflow hits record high in 2021". New Age (Bangladesh). 2 January 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ 2011 Census: Ethnic Group, local authorities in the United Kingdom, 11 October 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Asian and Pacific Islander Population in the United States". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Kibria, Nazli (2022), "The Emerging Diaspora of Bangladesh: Fifty Years of Overseas Movements and Settlements", The Emergence of Bangladesh, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 355–368, doi:10.1007/978-981-16-5521-0_20, ISBN 978-981-16-5520-3, S2CID 247070599, retrieved 21 July 2023

- ^ Nahar, Kamrun (13 June 2011). "Maldives to deport thousands of illegal Bangladeshi workers". The Financial Express.

Maldivian foreign minister Ahmed Naseem last week said some 50,000 Bangladeshi are now working in his country --- a nation of only around 400,000 people --- with one-third having no valid documents or registration.

- ^ "Bangladesh braced to receive hundreds of thousands of returnee migrant workers". Arab News. 29 June 2020.

- ^ a b "United Arab Emirates Population Statistics (2020)". Global Media Insight. 7 July 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Bangladeshis top expatriate force in Oman". Gulf News. 12 July 2018.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality - 2019 report". Priya Dsouza. 15 August 2019.

- ^ "Bangladeshi Workers: Around 2 lakh may have to leave Kuwait". The Daily Star. 15 July 2020.

- ^ "More illegal Bangladeshi workers enter Bahraini labor market". Xinhua News Agency. 12 March 2017.

- ^ The Muslim Society and Politics in Bengal, A.D. 1757-1947. University of Dacca. 1978. p. 76.

Maulana Murad, a Bengali domicile

- ^ 체류외국인 국적별 현황, K2WebWizard 2013년도 출입국통계연보, Ministry of Justice, 2013, p. 290, retrieved 5 June 2014

- ^ Admissions as of 12 July 2009. "Bandhobi (Movie - 2009)". HanCinema. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Kitahara, Reiko; Otsuki, Toshio (22 March 2018). "A study on the living environment of Bangladeshi foreign residents in Kita-ku, Tokyo: Influence on the concentrated area in a receiving country of migrant workers from chain migration based on international labor movement". Japan Architectural Review. 1 (3). Wiley Online Library: 371–384. doi:10.1002/2475-8876.12029.

- ^ "South Asian eateries in U.S. distinguishing cuisine from 'Indian food' umbrella". NBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (7 April 2000). "The Star of Bangladesh; In New York, Don't Take 'Indian' Food Too Literally". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Hasan, Sadiba (21 April 2023). "South Asian Muslims Herald Eid al-Fitr with a Night of Communal Revelry". The New York Times.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. "People in Australia who were born in Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Mahmud, Ezaz (19 May 2021). "Livelihoods of Bangladeshis at stake in Covid-19 hit Brazil". The Daily Star. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ Colebrooke, Thomas Edward (1884). "First Start in Diplomacy". Life of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9781108097222.

- ^ Khaleeli, Homa (8 January 2012). "The curry crisis". The Guardian.

- ^ Cuopo, Diego (June 2017). "Explaining the Bangladeshi migrant surge into Italy". The New Humanitarian.

- ^ "Bangladesh Community in Italy". Embassy of the People's Republic of Bangladesh -Rome.