Discrimination

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong,[1] such as race, gender, age, species, religion, physical attractiveness or sexual orientation.[2] Discrimination typically leads to groups being unfairly treated on the basis of perceived statuses based on ethnic, racial, gender or religious categories.[2][3] It involves depriving members of one group of opportunities or privileges that are available to members of another group.[4]

Discriminatory traditions, policies, ideas, practices and laws exist in many countries and institutions in all parts of the world, including some, where such discrimination is generally decried. In some places, countervailing measures such as quotas have been used to redress the balance in favor of those who are believed to be current or past victims of discrimination. These attempts have often been met with controversy, and sometimes been called reverse discrimination.

Etymology

[edit]The term discriminate appeared in the early 17th century in the English language. It is from the Latin discriminat- 'distinguished between', from the verb discriminare, from discrimen 'distinction', from the verb discernere (corresponding to "to discern").[5] Since the American Civil War the term "discrimination" generally evolved in American English usage as an understanding of prejudicial treatment of an individual based solely on their race, later generalized as membership in a certain socially undesirable group or social category.[6] Before this sense of the word became almost universal, it was a synonym for discernment, tact and culture as in "taste and discrimination", generally a laudable attribute; to "discriminate against" being commonly disparaged.[7][8][page needed]

Definitions

[edit]Moral philosophers[who?] have defined[when?] discrimination using a moralized definition. Under this approach, discrimination is defined as acts, practices, or policies that wrongfully impose a relative disadvantage or deprivation on persons based on their membership in a salient social group.[9] This is a comparative definition. An individual need not be actually harmed in order to be discriminated against. He or she just needs to be treated worse than others for some arbitrary reason. If someone decides to donate to help orphan children, but decides to donate less, say, to children of a particular race out of a racist attitude, he or she will be acting in a discriminatory way even if he or she actually benefits the people he discriminates against by donating some money to them.[10] Discrimination also develops into a source of oppression, the action of recognizing someone as 'different' so much that they are treated inhumanly and degraded.[11]

This moralized definition of discrimination is distinct from a non-moralized definition - in the former, discrimination is wrong by definition, whereas in the latter, this is not the case.[12]

The United Nations stance on discrimination includes the statement: "Discriminatory behaviors take many forms, but they all involve some form of exclusion or rejection."[13] The United Nations Human Rights Council and other international bodies work towards helping ending discrimination around the world.

Types

[edit]Age

[edit]Ageism or age discrimination is discrimination and stereotyping based on the grounds of someone's age.[14] It is a set of beliefs, norms, and values which used to justify discrimination or subordination based on a person's age.[15] Ageism is most often directed toward elderly people, or adolescents and children.[16][17]

Age discrimination in hiring has been shown to exist in the United States. Joanna Lahey, professor at The Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M, found that firms are more than 40% more likely to interview a young adult job applicant than an older job applicant.[18] In Europe, Stijn Baert, Jennifer Norga, Yannick Thuy and Marieke Van Hecke, researchers at Ghent University, measured comparable ratios in Belgium. They found that age discrimination is heterogeneous by the activity older candidates undertook during their additional post-educational years. In Belgium, they are only discriminated if they have more years of inactivity or irrelevant employment.[19]

In a survey for the University of Kent, England, 29% of respondents stated that they had suffered from age discrimination. This is a higher proportion than for gender or racial discrimination. Dominic Abrams, social psychology professor at the university, concluded that ageism is the most pervasive form of prejudice experienced in the UK population.[20]

Caste

[edit]According to UNICEF and Human Rights Watch, caste discrimination affects an estimated 250 million people worldwide and is mainly prevalent in parts of Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Japan) and Africa.[21][22] As of 2011[update], there were 200 million Dalits or Scheduled Castes (formerly known as "untouchables") in India.[23]

Disability

[edit]Discrimination against people with disabilities in favor of people who are not is called ableism or disablism. Disability discrimination, which treats non-disabled individuals as the standard of 'normal living', results in public and private places and services, educational settings, and social services that are built to serve 'standard' people, thereby excluding those with various disabilities. Studies have shown that disabled people not only need employment in order to be provided with the opportunity to earn a living but they also need employment in order to sustain their mental health and well-being. Work fulfils a number of basic needs for an individual such as collective purpose, social contact, status, and activity.[24] A person with a disability is often found to be socially isolated and work is one way to reduce his or her isolation. In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act mandates the provision of equality of access to both buildings and services and is paralleled by similar acts in other countries, such as the Equality Act 2010 in the UK.

Excellence

[edit]Language

[edit]

Linguistic discrimination (also called glottophobia, linguicism and languagism) is unfair treatment of people based upon their use of language and the characteristics of their speech, such as their first language, their accent, the perceived size of their vocabulary (whether or not the speaker uses complex and varied words), their modality, and their syntax.[31] For example, an Occitan speaker in France will probably be treated differently from a French speaker.[32] Based on a difference in use of language, a person may automatically form judgments about another person's wealth, education, social status, character or other traits, which may lead to discrimination. This has led to public debate surrounding localisation theories, likewise with overall diversity prevalence in numerous nations across the West.

Linguistic discrimination was at first considered an act of racism. In the mid-1980s, linguist Tove Skutnabb-Kangas captured the idea of language-based discrimination as linguicism, which was defined as "ideologies and structures which are used to legitimize, effectuate, and reproduce unequal divisions of power and resources (both material and non-material) between groups which are defined on the basis of language".[33] Although different names have been given to this form of discrimination, they all hold the same definition. Linguistic discrimination is culturally and socially determined due to preference for one use of language over others.

Scholars have analyzed the role of linguistic imperialism in linguicism, with some asserting that speakers of dominant languages gravitate towards discrimination against speakers of other, less dominant languages, while disadvantaging themselves linguistically by remaining monolingual.[34] According to scholar Carolyn McKinley, this phenomenon is most present in Africa, where the majority of the population speaks European languages introduced during the colonial era; African states are also noted as instituting European languages as the main medium of instruction, instead of indigenous languages.[34] UNESCO reports have noted that this has historically benefitted only the African upper class, conversely disadvantaging the majority of Africa's population who hold varying level of fluency in the European languages spoken across the continent.[34] Scholars have also noted impact of the linguistic dominance of English on academic discipline; scholar Anna Wierzbicka has described disciplines such as social science and humanities being "locked in a conceptual framework grounded in English" which prevents academia as a whole from reaching a "more universal, culture-independent perspective".[35]Name

[edit]Discrimination based on a person's name may also occur, with researchers suggesting that this form of discrimination is present based on a name's meaning, its pronunciation, its uniqueness, its gender affiliation, and its racial affiliation.[36][37][38][39][40] Research has further shown that real world recruiters spend an average of just six seconds reviewing each résumé before making their initial "fit/no fit" screen-out decision and that a person's name is one of the six things they focus on most.[41] France has made it illegal to view a person's name on a résumé when screening for the initial list of most qualified candidates. Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands have also experimented with name-blind summary processes.[42] Some apparent discrimination may be explained by other factors such as name frequency.[43] The effects of name discrimination based on a name's fluency is subtle, small and subject to significantly changing norms.[44]

Nationality

[edit]The Anti-discrimination laws of most countries allow and make exceptions for discrimination based on nationality and immigration status.[45] The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) does not prohibit discrimination by nationality, citizenship or naturalization but forbids discrimination "against any particular nationality".[46]

Discrimination on the basis of nationality is usually included in employment laws[47] (see above section for employment discrimination specifically). It is sometimes referred to as bound together with racial discrimination[48] although it can be separate. It may vary from laws that stop refusals of hiring based on nationality, asking questions regarding origin, to prohibitions of firing, forced retirement, compensation and pay, etc., based on nationality.

Discrimination on the basis of nationality may show as a "level of acceptance" in a sport or work team regarding new team members and employees who differ from the nationality of the majority of team members.[49]

In the GCC states, in the workplace, preferential treatment is given to full citizens, even though many of them lack experience or motivation to do the job. State benefits are also generally available for citizens only.[50] Westerners might also get paid more than other expatriates.[51]

Race or ethnicity

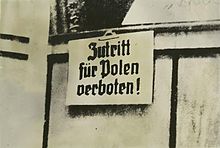

[edit]

Racial and ethnic discrimination differentiates individuals on the basis of real and perceived racial and ethnic differences and leads to various forms of the ethnic penalty.[52][53] It can also refer to the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to physical appearance and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another.[54][55][56][57] It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against other people because they are of a different race or ethnicity.[55][56] Modern variants of racism are often based in social perceptions of biological differences between peoples. These views can take the form of social actions, practices or beliefs, or political systems in which different races are ranked as inherently superior or inferior to each other, based on presumed shared inheritable traits, abilities, or qualities.[55][56][58] It has been official government policy in several countries, such as South Africa during the apartheid era. Discriminatory policies towards ethnic minorities include the race-based discrimination against ethnic Indians and Chinese in Malaysia[59] After the Vietnam War, many Vietnamese refugees moved to Australia and the United States, where they faced discrimination.[60]

Region

[edit]Regional or geographic discrimination is a form of discrimination that is based on the region in which a person lives or the region in which a person was born. It differs from national discrimination because it may not be based on national borders or the country in which the victim lives, instead, it is based on prejudices against a specific region of one or more countries. Examples include discrimination against Chinese people who were born in regions of the countryside that are far away from cities that are located within China, and discrimination against Americans who are from the southern or northern regions of the United States. It is often accompanied by discrimination that is based on accent, dialect, or cultural differences.[61]

Religious beliefs

[edit]| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

Religious discrimination is valuing or treating people or groups differently because of what they do or do not believe in or because of their feelings towards a given religion. For instance, the Jewish population of Germany, and indeed a large portion of Europe, was subjected to discrimination under Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party between 1933 and 1945. They were forced to live in ghettos, wear an identifying star of David on their clothes, and sent to concentration and death camps in rural Germany and Poland, where they were to be tortured and killed, all because of their Jewish religion. Many laws (most prominently the Nuremberg Laws of 1935) separated those of Jewish faith as supposedly inferior to the Christian population.

Restrictions on the types of occupations that Jewish people could hold were imposed by Christian authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to religious Jews, pushing them into marginal roles that were considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, occupations that were only tolerated as a "necessary evil".[62] The number of Jews who were permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos and banned from owning land. In Saudi Arabia, non-Muslims are not allowed to publicly practice their religions and they cannot enter Mecca and Medina.[63][64] Furthermore, private non-Muslim religious gatherings might be raided by the religious police.[64] In Maldives, non-Muslims living and visiting the country are prohibited from openly expressing their religious beliefs, holding public congregations to conduct religious activities, or involving Maldivians in such activities. Those expressing religious beliefs other than Islam may face imprisonment of up to five years or house arrest, fines ranging from 5,000 to 20,000 rufiyaa ($320 to $1,300), and deportation.[65]

In a 1979 consultation on the issue, the United States commission on civil rights defined religious discrimination in relation to the civil rights which are guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Whereas religious civil liberties, such as the right to hold or not to hold a religious belief, are essential for Freedom of Religion (in the United States as secured by the First Amendment), religious discrimination occurs when someone is denied "equal protection under the law, equality of status under the law, equal treatment in the administration of justice, and equality of opportunity and access to employment, education, housing, public services and facilities, and public accommodation because of their exercise of their right to religious freedom".[66]

Sex, sex characteristics, gender, and gender identity

[edit]Sexism is a form of discrimination based on a person's sex or gender. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles,[67][68] and may include the belief that one sex or gender is intrinsically superior to another.[69] Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.[70] Gender discrimination may encompass sexism and is discrimination toward people based on their gender identity[71] or their gender or sex differences.[72] Gender discrimination is especially defined in terms of workplace inequality.[72] It may arise from social or cultural customs and norms.[73]

Intersex persons experience discrimination due to innate, atypical sex characteristics. Multiple jurisdictions now protect individuals on grounds of intersex status or sex characteristics. South Africa was the first country to explicitly add intersex to legislation, as part of the attribute of 'sex'.[74] Australia was the first country to add an independent attribute, of 'intersex status'.[75][76] Malta was the first to adopt a broader framework of 'sex characteristics', through legislation that also ended modifications to the sex characteristics of minors undertaken for social and cultural reasons.[77][78] Global efforts such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 is also aimed at ending all forms of discrimination on the basis of gender and sex.[79]

Sexual orientation

[edit]

One's sexual orientation is a "predilection for homosexuality, heterosexuality, or bisexuality".[80] Like most minority groups, homosexuals and bisexuals are vulnerable to prejudice and discrimination from the majority group. They may experience hatred from others because of their sexuality; a term for such hatred based upon one's sexual orientation is often called homophobia. Many continue to hold negative feelings towards those with non-heterosexual orientations and will discriminate against people who have them or are thought to have them. People of other uncommon sexual orientations also experience discrimination. One study found its sample of heterosexuals to be more prejudiced against asexual people than against homosexual or bisexual people.[81]

Employment discrimination based on sexual orientation varies by country. Revealing a lesbian sexual orientation (by means of mentioning an engagement in a rainbow organisation or by mentioning one's partner name) lowers employment opportunities in Cyprus and Greece but overall, it has no negative effect in Sweden and Belgium.[82][83][84][85] In the latter country, even a positive effect of revealing a lesbian sexual orientation is found for women at their fertile ages.

Besides these academic studies, in 2009, ILGA published a report based on research carried out by Daniel Ottosson at Södertörn University College in Stockholm, Sweden. This research found that of the 80 countries around the world that continue to consider homosexuality illegal, five carry the death penalty for homosexual activity, and two do in some regions of the country.[86] In the report, this is described as "State sponsored homophobia".[87] This happens in Islamic states, or in two cases regions under Islamic authority.[88][89] On February 5, 2005, the IRIN issued a reported titled "Iraq: Male homosexuality still a taboo". The article stated, among other things that honor killings by Iraqis against a gay family member are common and given some legal protection.[90] In August 2009, Human Rights Watch published an extensive report detailing torture of men accused of being gay in Iraq, including the blocking of men's anuses with glue and then giving the men laxatives.[91] Although gay marriage has been legal in South Africa since 2006, same-sex unions are often condemned as "un-African".[92] Research conducted in 2009 shows 86% of black lesbians from the Western Cape live in fear of sexual assault.[93]

A number of countries, especially those in the Western world, have passed measures to alleviate discrimination against sexual minorities, including laws against anti-gay hate crimes and workplace discrimination. Some have also legalized same-sex marriage or civil unions in order to grant same-sex couples the same protections and benefits as opposite-sex couples. In 2011, the United Nations passed its first resolution recognizing LGBT rights.

Reverse discrimination

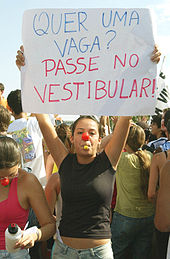

[edit]

Reverse discrimination is discrimination against members of a dominant or majority group, in favor of members of a minority or historically disadvantaged group.[94]

This discrimination may seek to redress social inequalities under which minority groups have had less access to privileges enjoyed by the majority group. In such cases it is intended to remove discrimination that minority groups may already face. Reverse discrimination can be defined as the unequal treatment of members of the majority groups resulting from preferential policies, as in college admissions or employment, intended to remedy earlier discrimination against minorities.[95]

Conceptualizing affirmative action as reverse discrimination became popular in the early- to mid-1970s, a time period that focused on under-representation and action policies intended to remedy the effects of past discrimination in both government and the business world.[96]

Anti-discrimination legislation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2022) |

Australia

[edit]- Racial Discrimination Act 1975

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992

- Age Discrimination Act 2004

Canada

[edit]Hong Kong

[edit]- Sex Discrimination Ordinance (1996)[citation needed]

India

[edit]Article 15 of the Constitution of India prohibits discrimination against any citizen on grounds of caste, religion, sex, race or place of birth etc.[98] Similarly, the Constitution of India guarantees several rights to all citizens irrespective of gender, such as right to equality under Article 14, right to life and personal liberty under Article 21.[99]

Indian Penal Code, 1860 (Section 153 A) - Criminalises the use of language that promotes discrimination or violence against people on the basis of race, caste, sex, place of birth, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or any other category.[100]

Israel

[edit]- Prohibition of Discrimination in Products, Services and Entry into Places of Entertainment and Public Places Law, 2000

- Employment (Equal Opportunities) Law, 1988

- Law of Equal Rights for Persons with Disabilities, 1998

Netherlands

[edit]- Article 137c, part 1 of Wetboek van Strafrecht prohibits insults towards a group because of its race, religion, sexual orientation (straight or gay), handicap (somatically, mental or psychiatric) in public or by speech, by writing or by a picture. Maximum imprisonment one year of imprisonment or a fine of the third category.[101][102]

- Part 2 increases the maximum imprisonment to two years and the maximum fine category to 4,[103] when the crime is committed as a habit or is committed by two or more persons.

- Article 137d prohibits provoking to discrimination or hate against the group described above. Same penalties apply as in article 137c.[104]

- Article 137e part 1 prohibits publishing a discriminatory statement, other than in formal message, or hands over an object (that contains discriminatory information) otherwise than on his request. Maximum imprisonment is 6 months or a fine of the third category.[101][105]

- Part 2 increases the maximum imprisonment to one year and the maximum fine category to 4,[103] when the crime is committed as a habit or committed by two or more persons.

- Article 137f prohibits supporting discriminatory activities by giving money or goods. Maximum imprisonment is 3 months or a fine of the second category.[106][107]

United Kingdom

[edit]- Equal Pay Act 1970 – provides for equal pay for comparable work.

- Sex Discrimination Act 1975 – makes discrimination against women or men, including discrimination on the grounds of marital status, illegal in the workplace.

- Human Rights Act 1998 – provides more scope for redressing all forms of discriminatory imbalances.

- Equality Act 2010 – consolidates, updates and supplements the prior Acts and Regulations that formed the basis of anti-discrimination law.[108][109][110]

United States

[edit]- Equal Pay Act of 1963[111] – (part of the Fair Labor Standards Act) – prohibits wage discrimination by employers and labor organizations based on sex.

- Civil Rights Act of 1964 – many provisions, including broadly prohibiting discrimination in the workplace including hiring, firing, workforce reduction, benefits, and sexually harassing conduct.[112]

- Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited discrimination in the sale or rental of housing based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity is charged with administering and enforcing the Act.

- Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, which amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – covers discrimination based upon pregnancy in the workplace.[113]

- Violence Against Women Act of 1994

- Racism still[when?] occurs in a widespread manner in real estate.[114]

United Nations documents

[edit]Important UN documents addressing discrimination include:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948. It states that:" Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status."[115]

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. The Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination. The convention was adopted and opened for signature by the United Nations General Assembly on December 21, 1965, and entered into force on January 4, 1969.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it came into force on September 3, 1981.

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is an international human rights instrument treaty of the United Nations. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that they enjoy full equality under the law. The text was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 13, 2006, and opened for signature on March 30, 2007. Following ratification by the 20th party, it came into force on May 3, 2008.

International cooperation

[edit]- Global Forum against Racism and Discrimination[116]

- The International Coalition of Inclusive and Sustainable Cities (ICCAR) launched by UNESCO in 2004[117]

- Routes of Enslaved Peoples project

Theories and philosophy

[edit]Social theories such as egalitarianism assert that social equality should prevail. In some societies, including most developed countries, each individual's civil rights include the right to be free from government sponsored social discrimination.[118] Due to a belief in the capacity to perceive pain or suffering shared by all animals, abolitionist or vegan egalitarianism maintains that the interests of every individual (regardless of their species), warrant equal consideration with the interests of humans, and that not doing so is speciesist.[119]

Philosophers have debated as to how inclusive the definition of discrimination should be. Some philosophers have argued that discrimination should only refer to wrongful or disadvantageous treatment in the context of a socially salient group (such as race, gender, sexuality etc.) within a given context. Under this view, failure to limit the concept of discrimination would lead to it being overinclusive; for example, since most murders occur because of some perceived difference between the perpetrator and the victim, many murders would constitute discrimination if the social salience requirement is not included. Thus this view argues that making the definition of discrimination overinclusive renders it meaningless. Conversely, other philosophers argue that discrimination should simply refer to wrongful disadvantageous treatment regardless of the social salience of the group, arguing that limiting the concept only to socially salient groups is arbitrary, as well as raising issues of determining which groups would count as socially salient. The issue of which groups should count has caused many political and social debates.[12]

Based on realistic-conflict theory[120] and social-identity theory,[121] Rubin and Hewstone[122] have highlighted a distinction among three types of discrimination:

- Realistic competition is driven by self-interest and is aimed at obtaining material resources (e.g., food, territory, customers) for the in-group (e.g., favoring an in-group in order to obtain more resources for its members, including the self).

- Social competition is driven by the need for self-esteem and is aimed at achieving a positive social status for the in-group relative to comparable out-groups (e.g., favoring an in-group in order to make it better than an out-group).

- Consensual discrimination is driven by the need for accuracy[123] and reflects stable and legitimate intergroup status hierarchies (e.g., favoring a high-status in-group because it is high status).

Labeling theory

[edit]

Discrimination, in labeling theory, takes form as mental categorization of minorities and the use of stereotype. This theory describes difference as deviance from the norm, which results in internal devaluation and social stigma[124] that may be seen as discrimination. It is started by describing a "natural" social order. It is distinguished between the fundamental principle of fascism and social democracy.[125][clarification needed] The Nazis in 1930s-era Germany and the pre-1990 Apartheid government of South Africa used racially discriminatory agendas for their political ends. This practice continues with some present day governments.[126]

Game theory

[edit]Economist Yanis Varoufakis (2013) argues that "discrimination based on utterly arbitrary characteristics evolves quickly and systematically in the experimental laboratory", and that neither classical game theory nor neoclassical economics can explain this.[127]

In 2002, Varoufakis and Shaun Hargreaves-Heap ran an experiment where volunteers played a computer-mediated, multiround hawk-dove game. At the start of each session, each participant was assigned a color at random, either red or blue. At each round, each player learned the color assigned to his or her opponent, but nothing else about the opponent. Hargreaves-Heap and Varoufakis found that the players' behavior within a session frequently developed a discriminatory convention, giving a Nash equilibrium where players of one color (the "advantaged" color) consistently played the aggressive "hawk" strategy against players of the other, "disadvantaged" color, who played the acquiescent "dove" strategy against the advantaged color. Players of both colors used a mixed strategy when playing against players assigned the same color as their own. The experimenters then added a cooperation option to the game, and found that disadvantaged players usually cooperated with each other, while advantaged players usually did not. They state that while the equilibria reached in the original hawk-dove game are predicted by evolutionary game theory, game theory does not explain the emergence of cooperation in the disadvantaged group. Citing earlier psychological work of Matthew Rabin, they hypothesize that a norm of differing entitlements emerges across the two groups, and that this norm could define a "fairness" equilibrium within the disadvantaged group.[128]

Effects on health

[edit]The psychological impact of discrimination on health refers to the cognitive pathways through which discrimination impacts mental and physical health in members of marginalized, subordinate, and low-status groups (e.g. racial and sexual minorities). Research on the relation between discrimination and health became a topic of interest in the 1990s, when researchers proposed that persisting racial/ethnic disparities in health outcomes could potentially be explained by racial/ethnic differences in experiences with discrimination.[129] Although the bulk of the research tend to focus on the interactions between interpersonal discrimination and health, researchers studying discrimination and health in the United States have proposed that institutional discrimination and cultural racism also give rise to conditions that contribute to persisting racial and economic health disparities.[130][131]

A stress and coping framework[132] is often applied to investigate how discrimination influences health outcomes in racial, gender, and sexual minorities, as well as on immigrants and indigenous populations.[133][134] Findings indicate that experiences of discrimination tend to translate into worse physical and mental health and lead to increased participation in unhealthy behaviors.[135] Evidence of the inverse link between discrimination and health has been consistent across multiple population groups and various cultural and national contexts.[136]See also

[edit]- Adultism

- Afrophobia

- Allport's Scale

- Anti-Arabism

- Anti-Catholicism

- Anti-intellectualism

- Anti-Iranian sentiment

- Anti-Mormonism

- Anti-Protestantism

- Antisemitism

- Antiziganism

- Aporophobia

- Apostasy

- Apostasy in Islam

- Atlantic slave trade

- Benevolent prejudice

- Bias

- Bumiputera (Malaysia)

- Civil and political rights

- Classicide

- Cultural appropriation

- Cultural assimilation

- Cultural genocide

- Dehumanization

- Dignity

- Discrimination against asexual people

- Discrimination against atheists

- Discrimination against drug addicts

- Discrimination against members of the armed forces in the United Kingdom

- Discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS

- Discrimination based on skin color

- Discrimination of excellence

- Economic discrimination

- Equal opportunity

- Equal rights

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnocentrism

- Figleaf

- Genetic discrimination

- Genocide

- Hate group

- Heightism

- Hispanophobia

- Homophobia

- Identicide

- In-group favoritism

- Ingroups and outgroups

- Institutional discrimination

- Institutional racism

- Intersectionality

- Intersex human rights

- Islamophobia

- Jim Crow laws

- List of anti-discrimination acts

- List of global issues

- Lookism

- Microaggression

- Minority stress

- Nativism (politics)

- Online hate speech

- Oppression

- Persecution

- Politicide

- Paradox of tolerance

- Racial segregation

- Religious intolerance

- Religious persecution

- Religious segregation

- Second-class citizen

- Sizeism

- Slavery

- Stigma management

- Structural discrimination

- Structural violence

- Supremacism

- Taste-based discrimination

- Transphobia

- Weightism

- Xenophobia

References

[edit]- ^ "What drives discrimination and how do we stop it?". www.amnesty.org. Amnesty International. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

Discrimination occurs when a person is unable to enjoy his or her human rights or other legal rights on an equal basis with others because of an unjustified distinction made in policy, law or treatment.

- ^ a b "Discrimination: What it is, and how to cope". American Psychological Association. October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

Discrimination is the unfair or prejudicial treatment of people and groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, age or sexual orientation.

- ^ "discrimination, definition". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Introduction to sociology. 7th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc, 2009. p. 334.

- ^ "Definition of discrimination; Origin". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Introduction to sociology (Print) (7th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. 2009. p. 324.

- ^ Simpson, J.A., ed. (1989). The Oxford Dictionary. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press. p. 758. ISBN 0-19861216-8.

- ^ Richard Tardif, ed. (1985). The Macquarie Concise Thesaurus — Australia's National Thesaurus. The Macquarie Library. ISBN 0-94975797-7.

- ^ Altman, Andrew (2020), "Discrimination", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved October 13, 2020,

[A]s a reasonable first approximation, we can say that discrimination consists of acts, practices, or policies that impose a relative disadvantage on persons based on their membership in a salient social group. [...] [W]e can refine the first-approximation account of discrimination and say that the moralized concept of discrimination is properly applied to acts, practices or policies that meet two conditions: a) they wrongfully impose a relative disadvantage or deprivation on persons based on their membership in some salient social group, and b) the wrongfulness rests (in part) on the fact that the imposition of the disadvantage is on account of the group membership of the victims.

- ^ Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, "Private Discrimination: A Prioritarian, Desert-Accommodating Account", San Diego Law Review, 43, 817-856 (2006); Oscar Horta, "Discrimination in Terms of Moral Exclusion", Theoria: Swedish Journal of Philosophy, 76, 346-364 (2010).

- ^ Thompson, Neil (2016). Anti-Discriminatory Practice: Equality, Diversity and Social Justice. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-58666-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Altman, Andrew (2020), "Discrimination", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved December 29, 2020

- ^ "United Nations CyberSchoolBus: What is discrimination?". Archived from the original on June 1, 2014.

- ^ "Definition of Ageism". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, George R.; Katsiaficas, George N.; Kirkpatrick, Robert George; Mary Lou Emery (1987). Introduction to critical sociology. Ardent Media. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-8290-1595-9. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Wilkinson J and Ferraro K, "Thirty Years of Ageism Research". In Nelson T (ed). Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002

- ^ "Young and Oppressed". youthrights.org. Retrieved April 11, 2012. Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lahey, J. (2005) Do Older Workers Face Discrimination? Boston College. Archived April 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Baert, S., Norga, J., Thuy, Y., Van Hecke, M. (In press) Getting Grey Hairs in the Labour Market: An Alternative Experiment on Age Discrimination Journal of Economic Psychology.

- ^ (2006) How Ageist is Britain? London: Age Concern. Archived October 27, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Discrimination". UNICEF. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011.

- ^ "Global Caste Discrimination". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "India: Official Dalit population exceeds 200 million". International Dalit Solidarity Network. May 29, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Vornholt, Katharina; Sjir Uitdewilligen; Frans J.N. Nijhuis (December 2013). "Factors Affecting the Acceptance of People with Disabilities at Work: A Literature Review". Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 23 (4): 463–75. doi:10.1007/s10926-013-9426-0. PMID 23400588. S2CID 10038886.

- ^ a b Puaschunder, Julia (August 2019). "Discrimination of Excellence: A Research Agenda" (PDF). Proceedings of the 14th International Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies (RAIS) Conference at the Erdman Center of Princeton University. 14 (1): 54–58. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3459603. S2CID 219357207.

- ^ a b De Vos, Marc (2020). "The European Court of Justice and the march towards substantive equality in European Union anti-discrimination law". International Journal of Discrimination and the Law. 20: 62–87. doi:10.1177/1358229120927947.

- ^ Chang, C.H. (2017). "How meritocracy is defined today?: Contemporary aspects of meritocracy". Recent Issues in Sociological Research. 10 (1): 112–121. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-1/8.

- ^ Hurwitz, Michael (2011). "The impact of legacy status on undergraduate admissions at elite colleges and universities". Economics of Education Review. 30 (3): 480–492. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.12.002.

- ^ Clayton, Thomas (1998). "Building the New Cambodia: Educational Destruction and Construction under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-1979". History of Education Quarterly. 38 (1): 1. doi:10.2307/369662.

- ^ Sauder, Michael (2020). "A Sociology of Luck". Sociological Theory. 38 (3): 193–216. doi:10.1177/0735275120941178. ISSN 0735-2751.

- ^ "Language Discrimination". Workplace Fairness. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Language Discrimination: Your Legal Rights" (PDF). ACLU Foundation of North California. The Legal Aid Society-Employment Law Center. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 4, 2012.

- ^ Quoted in Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Phillipson, Robert, "'Mother Tongue': The Theoretical and Sociopolitical Construction of a Concept". In Ammon, Ulrich (ed.) (1989). Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties, p. 455. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 3-11-011299-X.

- ^ a b c Dommisse, Ebbe (November 16, 2016). "Single dominant tongue keeps inequality in place". The Business Day. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ Anna Wierzbicka, Professor of Linguistics, Australian National University and author of 'Imprisoned by English, The Hazards of English as a Default Language, written in Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM), the universally convertible currency of communication, which can serve as a common auxiliary inter-language for speakers of different languages and a global means for clarifying, elucidating, storing, and comparing ideas" (194) (book review)

- ^ Silberzhan, Raphael (May 19, 2013). "It Pays to be Herr Kaiser". Psychological Science. 24 (12): 2437–2444. doi:10.1177/0956797613494851. PMID 24113624. S2CID 30086487.

- ^ Laham, Simon (December 9, 2011). "The name-pronunciation effect: Why people like Mr. Smith more than Mr. Colquhoun". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48 (2012): 752–756. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.002. S2CID 6757690.

- ^ Cotton, John (July 2007). "The "name game": affective and hiring reactions to first names". Journal of Managerial Psychology. 23 (1): 18–39. doi:10.1108/02683940810849648. S2CID 4484088.

- ^ Bertrand, Marianne (September 2004). "Are Emily and Brendan More Employable than Lakisha and Jamaal?" (PDF). The American Economic Review. 94 (4): 991–1013. doi:10.1257/0002828042002561.

- ^ Easton, Stephen (June 30, 2017). "Blind recruiting study suggests positive discrimination common in the APS". The Mandarin.

- ^ Smith, Jacquelyn (November 4, 2014). "Here's What Recruiters Look At In The 6 Seconds They Spend On Your Résumé". Business Insider.

- ^ "No names, no bias". The Economist. October 29, 2015.

- ^ Silberzhan, Raphael; Simonsohn, Uri; Uhlmann, Eric (February 4, 2014). "Matched-Names Analysis Reveals No Evidence of Name-Meaning Effects: A Collaborative Commentary on Silberzahn and Uhlmann" (PDF). Psychological Science. 25 (7): 1504–1505. doi:10.1177/0956797614533802. PMID 24866920. S2CID 26814316.

- ^ "The Power of Names". The New York Times. May 29, 2013.

- ^ Fennelly, David; Murphy, Clíodhna (2021). "Racial Discrimination and Nationality and Migration Exceptions: Reconciling CERD and the Race Equality Directive". Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights. 39 (4): 308–328. doi:10.1177/09240519211055648. S2CID 243839359.

- ^ International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

- ^ Race, Color, National Origin and Ancestry, State of Wisconsin Archived October 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Race and National Origin Discrimination". Office for Civil Rights. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Christiane Schwieren, Mechanisms Underlying Nationality-Based Discrimination in Teams. A Quasi-Experiment Testing Predictions From Social Psychology and Microeconomics Archived 2015-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Maastricht University

- ^ Ayesha Almazroui (March 18, 2013). "Emiratisation won't work if people don't want to learn". Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "'Western workers favoured in UAE', survey respondents say". The National. April 18, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Kislev, Elyakim (September 19, 2016). "Deciphering the 'Ethnic Penalty' of Immigrants in Western Europe: A Cross-Classified Multilevel Analysis". Social Indicators Research. 134 (2): 725–745. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1451-x. S2CID 157454886.

- ^ Carmichael, F.; Woods, R. (2000). "Ethnic Penalties in Unemployment and Occupational Attainment: Evidence for Britain". International Review of Applied Economics. 14 (1): 71–98. doi:10.1080/026921700101498. S2CID 154020583.

- ^ Dennis, Rutledge M. (1995). "Social Darwinism, scientific racism, and the metaphysics of race". Journal of Negro Education. 64 (3): 243–52. doi:10.2307/2967206. JSTOR 2967206.

- ^ a b c Racism Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ a b c Ghani, Navid (2008). "Racism". In Schaefer, Richard T. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE. pp. 1113–1115. ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2.

- ^ Newman, D. M. (2012). Sociology : exploring the architecture of everyday life (9th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-4129-8729-5.

racism: Belief that humans are subdivided into distinct groups that are different in their social behavior and innate capacities and that can be ranked as superior or inferior.

- ^ Newman, D.M. (2012). Sociology: exploring the architecture of everyday life (9th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-4129-8729-5.

racism: Belief that humans are subdivided into distinct groups that are different in their social behavior and innate capacities and that can be ranked as superior or inferior.

- ^ "Malaysia's lingering ethnic divide". March 4, 2008. BBC News.

- ^ Levine, Bertram. (2005). "Not All Black and White". J. Cropp (Ed.), Resolving Racial Conflict, 193-218. London: University of Missouri Press.

- ^ "Accent Discrimination Law and Legal Definition". USLegal.

- ^ "Did Discrimination Enhance Intelligence of Jews?". National Geographic News. July 18, 2005

- ^ Sandra Mackey's account of her attempt to enter Mecca in Mackey, Sandra (1987). The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-393-32417-4.

- ^ a b Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (September 19, 2008). "Saudi Arabia". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Maldives". United States Department of State. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1979: Religious discrimination. A neglected issue. A consultation sponsored by the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Washington. D.C., April 9–10, 1979

- ^ Matsumoto, David (2001). The Handbook of Culture and Psychology. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-19-513181-9.

- ^ Nakdimen, K. A. (1984). "The Physiognomic Basis of Sexual Stereotyping". American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (4): 499–503. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.4.499. PMID 6703126.

- ^ Witt, Jon (2017). SOC 2018 (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781259702723. OCLC 968304061.[page needed]

- ^ Forcible Rape Institutionalized Sexism in the Criminal Justice System| Gerald D. Robin Division of Criminal Justice, University of New Haven

- ^ Macklem, Tony (2003). Beyond Comparison: Sex and Discrimination. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82682-2.

- ^ a b Sharyn Ann Lenhart (2004). Clinical Aspects of Sexual Harassment and Gender Discrimination: Psychological Consequences and Treatment Interventions. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-1135941314. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

GENDER OR SEX DISCRIMINATION: This term refers to the types of gender bias that have a negative impact. The term has legal, as well as theoretical and psychological, definitions. Psychological consequences can be more readily inferred from the latter, but both definitions are of significance. Theoretically, gender discrimination has been described as (1) the unequal rewards that men and women receive in the workplace or academic environment because of their gender or sex difference (DiThomaso, 1989); (2) a process occurring in work or educational settings in which an individual is overtly or covertly limited access to an opportunity or a resource because of a sex or is given the opportunity or the resource reluctantly and may face harassment for picking it (Roeske & Pleck, 1983); or (3) both.

- ^ Christina Macfarlane, Sean Coppack and James Masters (September 12, 2019). "FIFA must act after death of Iran's 'Blue Girl,' says activist". CNN.

- ^ Judicial Matters Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2005, Republic of South Africa, Vol. 487, Cape Town, January 11, 2006.

- ^ "Australian Parliament, Explanatory Memorandum to the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Bill 2013". Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ We welcome the Senate Inquiry report on the Exposure Draft of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012 Archived 2014-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, Organisation Intersex International Australia, February 21, 2013.

- ^ Cabral, Mauro (April 8, 2015). "Making depathologization a matter of law. A comment from GATE on the Maltese Act on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics". Global Action for Trans Equality. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ "OII-Europe applauds Malta's Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act. This is a landmark case for intersex rights within European law reform". Oii Europe. April 1, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ sdgcounting (June 6, 2017). "SDG 5 Indicators". Medium. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ World English Dictionary, "Sexual Orientation"

- ^ MacInnis, Cara C.; Hodson, Gordon (2012). "Intergroup bias toward "Group X": Evidence of prejudice, dehumanization, avoidance, and discrimination against asexuals". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 15 (6): 725–743. doi:10.1177/1368430212442419. S2CID 3056711.

- ^ Drydakis, Nick (2011). "Women's Sexual Orientation and Labor Market Outcomes in Greece". Feminist Economics. 17: 89–117. doi:10.1080/13545701.2010.541858. S2CID 154771144.

- ^ Drydakis, Nick (2014). "Sexual orientation discrimination in the Cypriot labour market. Distastes or uncertainty?". International Journal of Manpower. 35 (5): 720–744. doi:10.1108/IJM-02-2012-0026. hdl:10419/62444. S2CID 10103299.

- ^ Ahmed, A. M., Andersson, L., Hammarstedt, M. (2011) Are gays and lesbians discriminated against in the hiring situation? Archived 2015-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation Working Paper Series 21.

- ^ Baert, Stijn (2014). "Career lesbians. Getting hired for not having kids?". Industrial Relations Journal. 45 (6): 543–561. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.467.2102. doi:10.1111/irj.12078. S2CID 34331459.

- ^ "New Benefits for Same-Sex Couples May Be Hard to Implement Abroad". ABC News. June 22, 2009.

- ^ "ILGA: 2009 Report on State Sponsored Homophobia (2009)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 2, 2010.

- ^ "ILGA:7 countries still put people to death for same-sex acts". Archived from the original on October 29, 2009.

- ^ "Islamic views of homosexuality". Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "AU welcomes progress in peace process". IRIN. September 29, 2004. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "They Want Us Exterminated". Human Rights Watch. August 16, 2009.

- ^ Harrison, Rebecca. "South African gangs use rape to "cure" lesbians". Reuters. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Kelly, Annie (March 12, 2009). "Raped and killed for being a lesbian: South Africa ignores 'corrective' attacks". The Guardian.

- ^ "Reverse Discrimination". Findlaw. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Reverse Discrimination". dictionary.com.

- ^ Embrick, David G. (2008). "Affirmative Action in Education". In Schaefer, Richard T. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, Volume 1. SAGE. pp. 12–19. ISBN 978-1-41-292694-2.

- ^ "What is Discrimination?". Canadian Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ "What is Article 15 of the Indian Constitution? Important Features and Provisions". Jagranjosh.com. May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Women rights in India". Archived from the original on December 6, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "Pawan Khera arrest | Section 153A: its use and misuse". The Indian Express. February 25, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ a b € 7,800

- ^ "wetten.nl – Regeling – Wetboek van Strafrecht – BWBR0001854". Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ a b € 19,500

- ^ "wetten.nl – Regeling – Wetboek van Strafrecht – BWBR0001854". Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "wetten.nl – Regeling – Wetboek van Strafrecht – BWBR0001854". Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ € 3,900

- ^ "wetten.nl – Regeling – Wetboek van Strafrecht – BWBR0001854". Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Equality considerations under the Equality Act 2010, including fulfilment of the PSED for the Collective Agreed Framework in relation to annual leave payments: additional guidance". GOV.UK. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Introduction and overview of the programme". GOV.UK. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Equality Act 2010: guidance". GOV.UK. June 16, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Equal Pay Act of 1963 – EPA – 29 U.S. Code Chapter 8 § 206(d)". Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1964 – CRA – Title VII – Equal Employment Opportunities – 42 US Code Chapter 21". Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Pregnancy Discrimination Act". Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Bouie, Jamelle (May 13, 2015). "A Tax on Blackness". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Archived from the original on December 8, 2014.

- ^ "Global Forum against Racism and Discrimination UNESCO". OHCHR. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "ICCAR | ECCAR". www.eccar.info. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Civil rights". Archived from the original on October 23, 1999. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Singer, Peter (1999) [1993]. "Equality for Animals?". Practical Ethics (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-521-43971-8.

If a being suffers, there can be no moral justification for refusing to take that suffering into consideration. ... This is why the limit of sentience ... is the only defensible boundary of concern for the interests of others. ... Similarly those I would call 'speciesists' give greater weight to their own species when there is a clash between their interests and the interests of those of other species.

- ^ Sherif, M. (1967). Group conflict and co-operation. London: Routledge.

- ^ Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. C. (1979). "An integrative theory of intergroup conflict". In Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. (eds.). The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. pp. 33–47.

- ^ Rubin, M.; Hewstone, M.; et al. (2004). "Social identity, system justification, and social dominance: Commentary on Reicher, Jost et al., and Sidanius et al". Political Psychology. 25 (6): 823–844. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00400.x. hdl:1959.13/27347.

- ^ "Prejudice & Discrimination Theories #2". Keith E Rice's Integrated SocioPsychology Blog & Pages. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Slattery, M. (2002). Key Ideas in Sociology. Nelson Thornes. pp. 134–137. ISBN 978-0-7487-6565-2.

- ^ Skoll, Geoffrey R. (2010). "The Theory of Fear / Chapter 3 / States and Social Control" (PDF). The Theory of Fear. doi:10.1057/9780230112636_3.

- ^ Adam, Heribert (July 1, 1996). "Anti-Semitism and Anti-Black Racism: Nazi Germany and Apartheid South Africa". Telos. 1996 (108): 25–46. doi:10.3817/0696108025. S2CID 145360794.

- ^ Yanis Varoufakis (2013). "Chapter 11: Evolving domination in the laboratory". Economic Indeterminacy: A personal encounter with the economists' peculiar nemesis. Routledge Frontiers of Political Economy. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-66849-1.

- ^ Shaun Hargreaves-Heap; Yanis Varoufakis (July 2002), "Some experimental evidence on the evolution of discrimination, co-operation and perceptions of fairness", The Economic Journal, 112 (481): 679–703, doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00735, S2CID 59133304

- ^ Krieger, Nancy (1999). "Embodying Inequality: A Review of Concepts, Measures, and Methods for Studying Health Consequences of Discrimination". International Journal of Health Services. 29 (2): 295–352. doi:10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. ISSN 0020-7314. PMID 10379455. S2CID 2742219.

- ^ Williams, David R.; Lawrence, Jourdyn A.; Davis, Brigette A. (April 1, 2019). "Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research". Annual Review of Public Health. 40 (1): 105–125. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. ISSN 0163-7525. PMC 6532402. PMID 30601726.

- ^ Mohai, Paul; Pellow, David; Roberts, J. Timmons (November 1, 2009). "Environmental Justice". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 34 (1): 405–430. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ Major, Brenda; Quinton, Wendy J.; McCoy, Shannon K. (2002), Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empirical advances, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 34, Elsevier, pp. 251–330, doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(02)80007-7, ISBN 9780120152346, retrieved November 15, 2022

- ^ Krieger, Nancy (2014). "Discrimination and Health Inequities". International Journal of Health Services. 44 (4): 643–710. doi:10.2190/HS.44.4.b. ISSN 0020-7314. PMID 25626224. S2CID 30287261.

- ^ Pascoe, Elizabeth A.; Smart Richman, Laura (2009). "Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (4): 531–554. doi:10.1037/a0016059. hdl:10161/11809. ISSN 1939-1455. PMC 2747726. PMID 19586161.

- ^ Inzlicht, Michael; McKay, Linda; Aronson, Joshua (2006). "Stigma as Ego Depletion: How Being the Target of Prejudice Affects Self-Control". Psychological Science. 17 (3): 262–269. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 16507068. S2CID 1930863.

- ^ Williams, David R.; Mohammed, Selina A. (2009). "Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 32 (1): 20–47. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. ISSN 0160-7715. PMC 2821669. PMID 19030981.