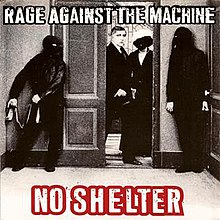

No Shelter

| "No Shelter" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Rage Against the Machine | ||||

| from the album Godzilla: The Album | ||||

| Released | May 19, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1998 | |||

| Genre | Rap metal[1] | |||

| Length | 4:03 | |||

| Label | Epic | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Tim Commerford, Zack de la Rocha, Tom Morello, Brad Wilk | |||

| Rage Against the Machine singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"No Shelter" is a song by American rock band Rage Against the Machine, released in 1998 on the Godzilla soundtrack. It can also be found as a bonus track on the Australian and Japanese release of The Battle of Los Angeles in 1999. The song is about how the mass media distracts the public from more important issues in the world and manipulates people's minds.

Lyric content

[edit]The song discusses consumerism and criticizes the feigned rebelliousness of teenaged consumerism, mentioning Nike and Coca-Cola particularly. Its central theme, however, is media control over public sentiment. In particular, it attacks the historical inaccuracy of Steven Spielberg’s film Amistad.

Despite appearing on the Godzilla soundtrack, the song contains the following line:

Godzilla, pure motherfucking filler; to get your eyes off the real killer.

"No Shelter" made its live debut on January 23, 1999, at a surprise club show at the Troubador in West Hollywood, CA.[2]

Critical response

[edit]Released "during the lull between Evil Empire and The Battle of Los Angeles" the band's critics held that the song's placement "in one of the biggest summer movies of 1998...reeked of selling out and hopping in bed with the enemy."[3] In response, guitarist Tom Morello told an interviewer for Kerrang! "A lot of times a soundtrack is an opportunity to collaborate with musicians you admire. It's an opportunity to work outside of your band, or exercise -- you know, to flex your musical abilities when Rage has downtime. Out of Godzilla, we happened to get a great song in No Shelter."[3]

Woodstock 1999

[edit]Appearing at Woodstock 1999, the band opened with the song. In a piece recalling his attendance at the performance, journalist David Samuels noted "The cultural contradictions involved in [RATM's] playing agitprop to a $150-a-ticket crowd are evident from the band's first song, "No Shelter," a Marcusian anthem and also the band's contribution to the soundtrack for the movie Godzilla. It is at once an angry grad-student rant, denouncing the cultural myth that "buyin' is rebellin'," and also proof of the near-infinite capacity of that culture to absorb any criticism as long as it features kick-ass guitars."[4]

Contextual irony

[edit]In the journal Studies in Popular Culture, scholar Jeffrey A. Hall examined the song in his essay "No Shelter in Popular Music: Irony and Appropriation in the Lyrical Criticism of Rage against the Machine".[5] Hall noted:

Lead vocalist Zack de la Rocha attacks the entertainment industry and Hollywood films like Rambo and Amistad, yet the most potent lyric clearly addresses the motion picture Godzilla, the film the soundtrack was to promote. ..Clearly not a typical motion picture promotion. Textual analysis of the raw and rapid-fire lyrics of No Shelter reveals a leftist political attack consistent with positions RATM advanced in concerts, lyrics, and their well-maintained website. A careful reading of the lyrics will reveal potent political attacks on the entertainment industry, the entirety of their rhetorical strategy is realized in the presence of this song on the soundtrack of Godzilla. Rage lyrically appropriates the soundtrack and utilizes the streamlined functioning of the corporate promotion to advance criticism of Godzilla and Hollywood's consumption of audiences and their cultural identity. ...The presence of Burkean irony and refraction in No Shelter demonstrates that the band acknowledges its role in the circular relationship between the text and its commercial context: the song is set forth as a promotion of the film and its soundtrack, and yet it returns as an assault on that very context. Their politically and commercially savvy attack on Godzilla creates the possibility of the very mechanisms that could stifle the impact of their leftist stance to be used to magnify and refract Rage's message throughout the chain of commercial promotion.[5]

Review

[edit]Billboard reviewed the song positively, stating "Zack de la Rocha's word-heavy verses share the song's spotlight equally with the driving guitars, which at times pleasantly and distinctly evoke the concept--of Hendrix. The band's calculated ethos is juxtaposed with unbridled instrumental interludes that make you think that perhaps, for a moment, it could let down its guard. But tension is the act's trademark, and on No Shelter, it comes through once again."[6]

Music video

[edit]The video has a retro 1920s "Golden Age" theme. It resembles the Industrial Revolution with scenes of workers in assembly lines, while company owners oversee the operations. The band plays throughout the video in a room that seems to be part of an abandoned building or factory. In the "board room", executives and developers plot out a sort of "helmet" with a video screen that covers the face. They experiment by putting the helmet on a teenager who is perturbed and upset. The video screen displays a mouth smiling. The executives declare the helmet a success and shake hands. They take the teenager away in a van and kill him in a remote area. Because the song was released for the 1998 film Godzilla, satirical "spoofs" of the movie's phrase "Size does matter" appear on billboards in the city scenes. They are:

- "Mumia Abu-Jamal's cell is this big" (a tiny cell) -- "Justice does matter!"

- "The crater at Hiroshima would stretch from here"... (zooms out to other end of city)... "to here." — "History does matter!"

- "Babies born into poverty in the U.S. each year would fill this building" (large building) — "Inequality does matter!"

- "Land stolen from Mexico equals five states" (darken area of US map, covering from California to Texas) — "Imperialism matters!"

Interspersed throughout is a montage depicting the Scottsboro Boys and the impending execution and death by electric chair of Sacco and Vanzetti, both historical examples of unfair trials. Tom Morello's Fender Telecaster guitar can be seen sporting communist references such as the Peruvian 'Sendero Luminoso' or Shining Path in Spanish.

References to popular culture

[edit]The song contains multiple references to popular culture, criticizing corporate advertising and capitalism. It mentions numerous products, films, brands, and other topics. Among them are Steven Spielberg, Amistad, the VCR, Fourth Reich, Americana, Coca-Cola, Rambo, Nike, and the aforementioned Godzilla series. This branding has resulted in the complete video being removed from some markets on YouTube due to threatened legal action by some of those brands.[citation needed]

Song appearances

[edit]- "No Shelter" was featured daily as the closing theme song on "Red Heat" on Hardcore Sports Radio Sirius channel 98 from the late fall of 2009 to mid-June 2010 at which point the show was augmented. The song is still featured as the closing before the augmented segment re-opens.

- Nick Turse mentioned the song in his book The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives. Turse wrote "In the late 1990s the otherwise dreadful soundtrack for Godzilla, that blockbuster-flop of a movie, featured one cut that transcended its origins. No Shelter, by rebel rap/rockers Rage Against the Machine...the group decried: 'Tha thin line between entertainment and war.' The line had by then grown thin indeed. Today, it hardly exists. The military is now in the midst of a full-scale occupation of the entertainment industry, conducted with far more skill (and enthusiasm on the part of the occupied) than America's debacle in Iraq."[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "No Shelter" in Popular Music: Irony and Appropriation in the Lyrical Criticism of Rage Against the Machine by Jeffrey A. Hall

- ^ Archive-Teri-vanHorn. "Rage Play New Tunes At Surprise Club Gig". MTV News. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Colin Devenish (2001). Rage Against The Machine. St Martin's Press.

- ^ David Samuels (November 1999). "Rock is Dead". Harpers Magazine.

- ^ a b Jeffrey A. Hall (2004). "Studies in Popular Culture". 26. Popular Culture Association in the South: 77–89.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Billboard". Howard Lander. June 27, 1998: 25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Nick Turse (2008). The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives. Metropolitan Books. p. 116. ISBN 9780805078961.