Highland branch

| Highland branch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

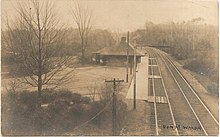

Newton Centre station after the 1905–1907 grade crossing project lowered the right-of-way | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Closed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Boston and Albany Railroad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1886 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 1958 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 12.25 mi (19.71 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Grade-separated double track | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Highland branch, also known as the Newton Highlands branch, was a suburban railway line in Boston, Massachusetts. It was opened by the Boston and Albany Railroad in 1886 to serve the growing community of Newton, Massachusetts. The line was closed in 1958 and sold to the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), the predecessor of the current Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), which reopened it in 1959 as a light rail line, now known as the D branch of the Green Line.

The first section of what became the Highland branch was built by the Boston and Worcester Railroad between Boston and Brookline in 1848. The Charles River Branch Railroad, a forerunner of the New York and New England Railroad, extended the line to Newton Upper Falls in 1852. The B&A bought the line in 1883 and extended to Riverside, rejoining its main line there. The MTA electrified the line when it rebuilt it for light rail use.

The conversion of the Highland branch into a light rail line was pioneering in several ways. Amid a backdrop of failing private passenger service in the United States, it was the first time a government entity in that country had assumed full responsibility for losses on a route. It was also the only example of converting an extant commuter rail line to light rail use.

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]What became the Highland branch was built in stages. The initial segment was the Boston and Worcester Railroad's Brookline branch, which opened on April 10, 1848. This line stretched 1.55 miles (2.49 km) from a junction with the Boston and Worcester main line south of Governor Square southwest to the current location of the Brookline Village station in Brookline, with an intermediate station at Longwood Avenue.[1][2] Construction costs were roughly $42,000.[3] Brookline had previously only been reachable by road (horsecar service on what is now Huntington Avenue did not begin until 1859), and the branch was quickly a success.[4][5]

Based on this success, the Charles River Branch Railroad was founded in 1849 to extend service west from Brookline.[5] Beginning in 1851, the railroad built 6.1 miles (9.8 km) from Brookline to Newton Upper Falls. This extension opened on November 24, 1852, at a cost not exceeding $253,000.[6] [7] The line was further extended to Great Plains (later part of Needham) the next year, and to Woonsocket, Rhode Island in 1863.[8] The Charles River Branch Railroad also constructed its own track parallel to the Brookline branch. From 1858, freight trains carrying gravel from Needham quarries to fill the Back Bay for development made up most of the traffic on the line.[8]

By the early 1870s the Boston and Worcester had become the Boston and Albany Railroad (B&A), itself destined to become part of the New York Central Railroad system. The tracks beyond Brookline, which now reached Woonsocket, Rhode Island, belonged to the New York and New England Railroad, a forerunner of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. New York and New England trains used the B&A's route via Brookline to reach Boston.[9]

Suburban service

[edit]

The citizens of Newton were dissatisfied with their service to Boston and since the early 1870s and had pressured both the Boston and Albany and the New York and New England to improve service, without result. Among these proposals was for the NY&NE to sell part of its Woonsocket line to the B&A, which would then build west through Newton Highlands to Riverside, on its main line from Boston to Albany, New York. This would create a loop or "circuit" between Boston and Riverside. The founding of the Newton Circuit Railroad by a group of Newton citizens in 1882, with the stated goal of completing the circuit by building a 7-mile (11 km) line from Brookline to Riverside, prompted the two railroads to take action.[10]

In 1883 the New York and New England sold the line between Brookline and Newton Highlands to the B&A for $411,400.[11] The B&A completed the missing 3 miles (4.8 km) and opened the new branch on May 16, 1886.[12] To encourage commuter traffic the B&A offered reduced-fare commutation tickets.[13] The introduction of frequent service to Boston led a population boom in Newton.[14] Three new stations on the extension opened as they were completed: Waban on August 16, 1886; Woodland soon afterwards; and Eliot in December 1888.[15] The level crossing at Aspinwall Avenue was replaced with a road bridge in 1892.[16]

Between 1905–1907 the Boston and Albany undertook a project to remove grade crossings along the branch, following a similar project a decade earlier on the main line through Newton.[17] The line's elevation was lowered by as much as 10.5-foot (3.2 m) in some places in order to permit road traffic to cross overhead. Lower levels were added at Newton Highlands and Newton Centre to accommodate the depressed tracks. At this time service over the line was almost exclusively passenger, with just one scheduled freight train per day.[18] An infill station at Beaconsfield to serve magnate Henry Melville Whitney's Beaconsfield Hotel opened in 1907.[19]

The New York Central Railroad had bought the B&A in 1900 primarily for long-distance service.[17] After the New York Central electrified several suburban lines around New York City, the public asked for similar improvements around Boston. The New York Central studied third-rail electrification of the Highland branch and the main line as far as Framingham in 1911, but did not find it to be cost-effective.[20] The lines instead continued to use steam power until diesel locomotives were substituted around 1950.[21]

Trains which traveled from Boston to Riverside via the Highland branch returned via the main line, thus completing the "circuit". In 1904 a round trip took 1 hour and 15 minutes.[22] The B&A main line was quadruple-tracked between Boston and Riverside; tracks 3 and 4 were used by suburban trains.[23] After the Needham cutoff opened in 1906, the New Haven rerouted most trains on the Charles River line via Forest Hills rather than the Highland branch to avoid congestion at the Cook Street junction. From 1911 to 1914, the New Haven operated "Needham Circuit" service operating via Needham and Newton Highlands.[24] In 1926, the Newton Lower Falls Branch was rerouted to join the Highland branch south of Riverside. The branch ran with overhead electrification between Newton Lower Falls and Riverside until 1930, then with locomotives until 1957.[20]

By November 1912, the Highland branch had 30 daily round trips, plus several Needham trains operating via Newton Highlands. This frequency dropped by one-quarter by 1919 (with many Highland branch trains not completing the circuit on the main line), then stayed constant for two decades.[17] The B&A upgraded Brookline Junction to centralized traffic control (CTC) in 1932, improving the flow of traffic between the branch and the main line.[25] By 1950, the Highland branch saw just seven daily round trips.[17]

Sale to MTA

[edit]

The Massachusetts state legislature had first proposed replacing the conventional train service on the Highland branch with streetcars running from the Tremont Street Subway in 1926.[26][27] The next major round of planning in the mid-1940s suggested the same conversion, along with a branch to Needham.[28][29] The idea returned in the mid-1950s as a combination of factors, both general and specific, made the concept attractive. The commuter rail business had ceased to be profitable for most railroads in the United States. Causes included high structural costs of doing business, loss of demand outside of rush hour, and restrictive regulations.[30] The Boston-area railroads were not immune to these trends, and as the decade wore on sought to end or reduce their money-losing commuter operations.[31] In addition, the extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike over part of the B&A main line would reduce its capacity going forward.[26] By 1957, daily ridership was just 3,100 passengers.[32]

The Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) first proposed buying the Highland branch and rebuilding it as a light rail line in 1956, for a total estimated cost of $9 million.[33] The MTA was attracted to the project because it could extend rapid transit service quickly and cheaply.[29] The state legislature approved the purchase and a total expenditure of $9.2 million on June 20, 1957.[26][34] By the time the New York Central ended the seven inbound and nine outbound daily trains on May 31, 1958, daily patronage on the branch had fallen to 2,200 passengers.[35][36] The MTA bought the Highland branch from the Boston and Albany on June 24, 1958 for $600,000.[37] Even as the MTA took this action, the Boston and Maine Railroad was reducing service on its lines radiating out of North Station and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad threatened to end all service on the Old Colony Railroad lines.[31]

Construction on the new light rail line began on July 10, 1958. A new 1,150-foot (350 m)-long tunnel was built to connect with the existing Beacon Street Line tunnel west of Kenmore Square. Streetcar stations with automobile parking were built at all the former station sites; Riverside and Woodland were both relocated to the southeast. Additional construction included a yard at Riverside; a loop, busway, and connection with the existing yard at Reservoir; an additional station at Park Drive; and overhead electrification including a new substation at the South Boston power station.[34] The MTA reopened the branch as the Riverside Line on July 4, 1959. Total construction costs came to $8 million. Daily ridership was 25,000, ten times what the B&A trains had carried at the end.[35][38] The project was "ahead of schedule and under budget", and ridership exceeded projections. The faster acceleration of the electric streetcars permitted faster operation between downtown and Riverside (35 minutes versus 40 minutes) than the conventional trains they replaced.[39] While other government entities were subsidizing passenger operations around the United States, it was the only example at that time of a government entity taking on the entire cost of what had been a private operation,[40] and the only case of a commuter rail line converted to light rail.[41] By 1960, the line was estimated to reduce rush hour congestion in downtown Boston by seven percent.[32]

Though successful, the conversion was cheaply constructed, and further upgrades were soon needed. From June 1960 to January 1961, the MTA enlarged Riverside Yard and added a maintenance facility, upgraded the power infrastructure, and improved the signalling system.[42] In 1967, the MBTA (which had replaced the MTA in 1964) designated the line as the Green Line D branch as part of systemwide rebranding.[43] Ridership on the surface section of the D branch has remained relatively constant since 1959 - a 2010-2011 count found 24,632 weekday boardings.[44] Short sections of the Highland branch remained connected at both ends for freight service until the 1970s. The Lower Falls branch between Newton Lower Falls and Riverside was out of service after 1972, leaving just the short section at Riverside Yard; the branch was formally abandoned in 1976.[45]

Route

[edit]The Highland branch diverged from the Boston and Albany main line at Brookline Junction, adjacent to Fenway Park. From there the branch continued southwest into Brookline. Shadowing the branch for this portion was the "Emerald Necklace", a partially-completed series of parks and waterways. At Brookline the line turned west and left the Muddy River behind.[46]

In Chestnut Hill the line passed south of the Chestnut Hill Reservoir, which opened in 1870. An even closer encounter took place in Newton Centre, where the line ran within a few feet of Crystal Lake. The grade crossing elimination project of 1905–1907 lowered the line in this area to 18 inches (460 mm) above the lake's surface level. The B&A installed a drainage system to mitigate the heightened flood risk.[47]

At Newton Highlands the New York and New England Railroad diverged at Cook Street Junction for Woonsocket. The Highland branch turned back toward the B&A main line, running northwest through Waban. It rejoined the main line at Riverside Junction, 12.25 miles (19.71 km) from Boston.[25]

Stations

[edit]

The creation of the circuit service over the Highland branch coincided with a "major program of capital investment and improvements" by the Boston and Albany.[48] Architect Henry Hobson Richardson, who had been involved with the B&A since 1867 and designed Auburndale station for the railroad in 1881, was commissioned to design several stations for the B&A. These included the three stations opened on the new section through Newton Highlands (Eliot, Waban, and Woodland), plus a new building (completed in 1884) for the existing Chestnut Hill station.[13] The three new stations were intended to attract real estate development to what were then lightly populated areas.[49]

After Richardson's death in 1886, his successor firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge designed a number of additional stations for the B&A, several of which were for the Highland branch. These included replacements for six of the former NY&NE stations - Newton Highlands in 1887, Reservoir in 1888, Newton Centre in 1891, Brookline Hills in 1892, and Longwood in 1894 - plus Riverside in 1894.[50] Most originally had their grounds designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.[51] Ignored in this renewal program was the circa-1870 Brookline station, dismissed by Charles Mulford Robinson in 1902 as "disappointing...a brick structure of an earlier date."[52]

Most of the stations were demolished during the light rail conversion to provide additional parking spaces. However, four structures remain: the station buildings at Newton Centre, Newton Highlands, and Woodland, plus part of the baggage and express building at Newton Centre.[51] (None of the Olmsted-designed landscaping survived.[51]) On March 25, 1976, the four structures were added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Newton Railroad Stations Historic District.[53] The structures at Newton Centre and Newton Highlands are in use by businesses, while the run-down Woodland station is used for storage by a golf course.[51]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Boston and Worcester Railroad 1848, p. 4: "The entire cost of the branch is not yet ascertained..."

- ^ Poor 1860, pp. 104–105

- ^ Boston and Worcester Railroad 1850, p. 7

- ^ Clarke & Cummings 1997, p. 60

- ^ a b Karr 2017, p. 351

- ^ Report of the Directors of the Boston and Worcester Railroad. Boston and Worcester Railroad. 1853. p. 9.

- ^ Poor 1860, p. 89: "The cost of the Charles River Branch road to the date of consolidation was $253,808."

- ^ a b Karr 2017, p. 352

- ^ "The Newton Circuit Railroad". American Railroad Journal: 415. June 17, 1882.

- ^ Ochsner 1988, p. 111

- ^ "Annual Reports: Boston & Albany". St. Louis Railway Register. Vol. 9, no. 10. March 8, 1884. p. 117.

- ^ Ochsner 1988, pp. 111–112

- ^ a b Ochsner 1988, p. 114

- ^ Fleishman 1999, p. 27

- ^ Ochsner 1982, pp. 360–366

- ^ "Aspinwall Av. to be Bridged". Boston Globe. July 8, 1892. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Humphrey & Clark 1985, p. 22

- ^ Whitney 1907, pp. 586–589

- ^ "New Engineering Work". Monthly Bulletin. Boston Society of Civil Engineers: 11. December 1906 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Humphrey & Clark 1986, p. 4

- ^ Humphrey & Clark 1986, p. 34

- ^ Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co. January 1904. p. 236. OCLC 6340864.

- ^ Humphrey & Clark 1985, p. 21

- ^ Humphrey & Clark 1985, p. 45

- ^ a b Curran 1932, p. 293

- ^ a b c Allen 1999, p. 42

- ^ Dana 1961, p. 2

- ^ Boston Elevated Railway; Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (April 1945), Air View: Present Rapid Transit System - Boston Elevated Railway and Proposed Extensions of Rapid Transit into Suburban Boston – via Wikimedia Commons

- ^ a b Clarke 2015, p. 155

- ^ Hilton 1962, pp. 173–175

- ^ a b Hurley, Cornelius F. (May 26, 1958). "State Must Act This Week To Keep Old Colony Running". North Adams Transcript. p. 7. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Dana 1961, p. 17

- ^ "MTA Has Plan To Extend Lines On B&A Roadbed". The Berkshire Eagle. September 6, 1956. p. 9. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Dana 1961, p. 4

- ^ a b "Boston Rides Old Rail Line On 20c Fare". The Pittsburgh Press. November 15, 1959. p. 43. Retrieved June 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Clarke 2015, p. 4

- ^ Hilton 1962, p. 177

- ^ Cheney & Sammarco 1999, p. 129

- ^ Allen 1999, p. 43

- ^ Hilton 1962, p. 181

- ^ Allen 1999, p. 40

- ^ Clarke 2015, p. 160

- ^ Belcher, Jonathan. "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). Boston Street Railway Association. p. 301. Page numbers are accurate to the December 21, 2018 version.

- ^ "Ridership and Service Statistics" (PDF) (14th ed.). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 2014. p. 2.17.

- ^ Karr 2017, p. 345

- ^ Whitney 1907, p. 586

- ^ Whitney 1907, p. 587

- ^ Ochsner 1988, p. 109

- ^ Ochsner 1988, p. 116

- ^ Ochsner 1988, pp. 127–131

- ^ a b c d Roy 2007, pp. 198–200, 261, 274

- ^ Robinson 1902, p. 568

- ^ "National Register Information System – Woodland, Newton Highlands, and Newton Centre Railroad Stations, and Baggage and Express Building (#76002137)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

References

[edit]- Report of the Directors of the Boston and Worcester Railroad. Boston: Dutton & Wentworth. June 5, 1848.

- Annual Report of the Directors of the Boston and Worcester Railroad. Boston: Eastburn's Press. 1850.

- Allen, John (1999). "Inner Zone Commuter Rail as an Opportunity for Light Rail: Lessons from Boston's Riverside Line". Transportation Research Record. 1677 (1): 40–47. doi:10.3141/1677-05. ISSN 0361-1981. S2CID 111002264.

- Cheney, Frank; Sammarco, Anthony M. (1999). Boston in Motion. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0087-4.

- Clarke, Bradley H.; Cummings, O.R. (1997). Tremont Street Subway: A Century of Public Service. Boston Street Railway Association. ISBN 978-0-938315-04-9.

- Clarke, Bradley H. (2015). Streetcar Lines of the Hub: Boston's MTA Through Riverside and Beyond. Boston Street Railway Association. ISBN 978-0-938315-07-0.

- Curran, J. W. (October 1932). "Remote Control with C.T.C. Equipment on Boston & Albany". Railway Signaling. 25 (10): 293–295.

- Dana, Edward (October 1960 – July 1961). "Riverside Line Extension, 1959". Transportation Bulletin. No. 65. Connecticut Valley Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society.

- Fleishman, Thelma (1999). Newton. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3774-0.

- Hilton, George W. (Summer 1962). "The Decline of Railroad Commutation". Business History Review. 36 (2): 171–187. doi:10.2307/3111454. ISSN 0007-6805. JSTOR 3111454. S2CID 155828018.

- Humphrey, Thomas J.; Clark, Norton D. (1985). Boston's Commuter Rail: The First 150 Years. Boston Street Railway Association. ISBN 978-0-685-41294-7.

- Humphrey, Thomas J.; Clark, Norton D. (1986). Boston's Commuter Rail: Second Section. Boston Street Railway Association. ISBN 978-0-938315-02-5.

- Karr, Ronald Dale (2017). The Rail Lines of Southern New England (2 ed.). Branch Line Press. ISBN 978-0-942147-12-4.

- Ochsner, Jeffery Karl (1982). H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-15023-1.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (June 1988). "Architecture for the Boston & Albany Railroad: 1881–1894". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 47 (2): 109–131. doi:10.2307/990324. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 990324.

- Poor, Henry Varnum (1860). History of the Railroads and Canals of the United States. Vol. 1. OCLC 950951354.

- Robinson, Charles Mulford (November 1902). "A Railroad Beautiful". House & Garden. Vol. 2, no. 11. pp. 564–570.

- Roy, John H. Jr. (2007). A Field Guide to Southern New England Railroad Depots and Freight Houses. Branch Line Press. ISBN 978-0-942147-08-7.</ref>

- Whitney, Walter C. (November 30, 1907). "Grade Crossing Abolition at Newton Highlands and Newton Centre, Mass". The Engineering Record. 56 (22): 586–589.