New Zealand–United States relations

| |

United States |

New Zealand |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of the United States, Wellington | Embassy of New Zealand, Washington, D.C. |

According to the U.S. State Department, relations between New Zealand and the United States as of August 2011 are "the best they have been in decades."[1] New Zealand is a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[2]

United States and New Zealand share comparable histories; both nations grew from British colonies and both boast indigenous populations of East Polynesian descent (Māori and Native Hawaiians). Both nations are known for their proximity to the Pacific Ocean, and the New Zealand-United States relationship is a key factor of Asia-Pacific geopolitics. Both states have also been part of a Western alliance of states in various wars. Together with three other Anglophone countries, they comprise the Five Eyes espionage and intelligence alliance.

History

[edit]

Cross-cultural similarities between the Māori (tangata māori) of precolonial Aotearoa and native Hawaiians (kanaka māoli) date back thousands of years. According to oral history, the Māori homeland is Hawaiki, a semi-mythical island from which the name of the state of Hawaii is derived.[3][4] The Māori language and the Hawaiian language are closely related Polynesian languages, to the extent that the Hawaiians' endonym Kānaka Maoli itself is cognate to Tangata Māori of the former[5] both deriving from Proto-Polynesian *ma(a)qoli, which has the reconstructed meaning "true, real, genuine".[6][7]

Pre-statehood era

[edit]The United States established consular representation in New Zealand in 1838 to represent and protect American shipping and whaling interests, appointing James Reddy Clendon as Consul, resident in Russell.[8] In 1840, New Zealand became part of the British Empire with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Although it gradually grew more independent, for its first hundred years, New Zealand followed the United Kingdom's lead on foreign policy. In declaring war on Germany on 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage proclaimed, "Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand".

New Zealand and the United States are old friends. While the United States is an immensely powerful nation, New Zealand is a small country, possessing for the most part only soft power, but with a record of deploying to help troubled nations find a way forward. New Zealand and the United States, with our strong shared values, can work together to shape a better world, as we are. That, and our strong economic, scientific, education, and people to people ties, makes this relationship a very important one to New Zealand, which we seek to strengthen.

While Hawaii was still an independent kingdom, many Hawaiian sailors in the 1850s settled at Papakōwhai not far from Wellington, where they were referred to with the exonym Wahu (after the island Oʻahu).[10] On the other hand, Māori New Zealanders quickly established a community at Manoa; they at one point gained the audience with Kamehameha and Kalākaua nobility in 1920.[11]

Conflicts fought alongside the United States

[edit]New Zealand has fought in a number of conflicts on the same side as the United States, including World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War and the Afghanistan War; it also sent a unit of army engineers to help rebuild Iraqi infrastructure during the Iraq War.

World War II

[edit]

During the Pacific theatre of WWII (1941–1945), significant numbers of US military personnel were deployed to New Zealand to prepare for crucial battles such as Guadalcanal and Tarawa;[1] there were between 15,000 and 45,000 US servicemen stationed in New Zealand at any one time between June 1942 and mid-1944.[12] The habits and spending power of these troops had various influences on New Zealand's culture.

Though relations were largely positive, some points of tension developed. For example, the 1st Marine Division, was tasked with loading reconfiguration from administrative to combat configuration during a strike by Wellington dock workers.[13] The Battle of Manners Street also occurred in Wellington involving American servicemen and New Zealand servicemen and civilians outside the Allied Services Club in Manners Street after American servicemen in the Services Club began forcibly stopping Māori soldiers from also using the Club because of their skin colour. Many New Zealand soldiers in the area, both white (Pākehā) and Māori, combined in opposition. The battle resulted in a possible two American deaths and 1 New Zealand Serviceman being arrested, as well as a cover up.

After the war New Zealand joined with Australia and the United States in the ANZUS security treaty in 1951.

ANZUS Treaty

[edit]

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS or ANZUS Treaty) is the military alliance which binds Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area, though today the treaty is understood to relate to defence operations. Initially the 1951 ANZUS Treaty was a fully mutual collective security alliance between Australia, New Zealand and the United States, but this is no longer the case as the United States suspended its treaty obligations to New Zealand following the refusal to allow an American destroyer, the USS Buchanan, into a New Zealand port in February 1985. A 1984 policy of a New Zealand nuclear-free zone meant that any ship thought to be carrying nuclear weapons was banned from New Zealand's ports, which meant all American naval vessels were essentially denied access due to the American policy to 'neither confirm nor deny' the presence of nuclear weapons.[15]

In suspending obligations to New Zealand under the ANZUS treaty, the US cut major military and diplomatic ties between Wellington and Washington, downgrading New Zealand from 'ally', to 'friend'.[16] This included removing New Zealand from military exercises and war games in the area, and limiting the intelligence sharing to New Zealand.[17] New Zealand has not removed itself from ANZUS, arguing that allowing nuclear weapons into New Zealand was not part of the ANZUS treaty, and that New Zealand's position is not a pacifist or Anti-American decision,[18] and would increase its conventional military cooperation with the US.[19] The Americans felt personally betrayed by the New Zealanders and would not accept the anti-nuclear stance,[20] stating that New Zealand will be welcome back in ANZUS if and when New Zealand accepted all US ship visits.[15] The New Zealand government passed the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987.[21] This Act formalized the previous policy of New Zealand being a nuclear-free zone and banned all nuclear-powered ships or nuclear weapons from entering New Zealand waters or air space.[22]

New Zealand's relationship with the United States further suffered when French agents sank the Rainbow Warrior while it was docked in Auckland Harbour in July 1985. The United States, as well as other western countries aside from Australia, failed to condemn the attack which was seen in New Zealand as state-sponsored terrorism by the French. This inaction furthered the breach between the two countries, with the US State Department finally stating that it "deplored such acts, wherever they may occur" in September 1985, a few days after the French admission of guilt.[23]

In 1996, the United States under President Bill Clinton reinstated New Zealand's status from a 'friend' to an 'ally' by designating New Zealand as a Major non-NATO ally.[24]

Although the ANZUS treaty has never been officially called on by the United States, New Zealand has continued to fight alongside the United States in multiple conflicts following the Second World War. Notably, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and Afghanistan.

Korean War 1950–1953

[edit]New Zealand was among those who responded to the United Nations call for help in Korea. New Zealand joined 15 other nations, including the United Kingdom and the United States, in the anti-communist war. The Korean War was also significant, as it marked New Zealand's first move towards association with the United States' stand against communism.[25]

New Zealand contributed six frigates, several smaller craft, and a 1044 strong volunteer force (known as K-FORCE) to the Korean War. The ships were under the command of a British flag officer[26] and formed part of the US Navy screening force during the Battle of Inchon, performing shore raids and inland bombardment. The last New Zealand soldiers did not leave until 1957 and a single liaison officer remained until 1971. A total of 3,794 New Zealand soldiers served in K-FORCE and 1300 in the Navy deployment. 33 were killed in action, 79 wounded and one soldier was taken prisoner. That prisoner was held in North Korea for eighteen months and repatriated after the armistices.

Vietnam War

[edit]

New Zealand's involvement in the Vietnam War was highly controversial, sparking widespread protest at home from anti-Vietnam War movements modelled on their American counterparts.[27] This conflict was also the first in which New Zealand did not fight alongside the United Kingdom, instead following the loyalties of the ANZUS Pact (Australia also fought in the war).[28]

New Zealand's initial response was carefully considered and characterised by Prime Minister Keith Holyoake's cautiousness towards the entire Vietnam question. New Zealand non-military economic assistance would continue from 1966 onwards and averaged at US$347,500 annually. This funding went to several mobile health teams to support refugee camps, the training of village vocational experts, to medical and teaching equipment for Huế University, equipment for a technical high school and a contribution toward the construction of a science building at the University of Saigon. Private civilian funding was also donated for 80 Vietnamese students to take scholarships in New Zealand.

The government preferred minimal involvement, with other Southeast Asian deployments already having a strain on the New Zealand armed forces. From 1961, New Zealand came under pressure from the United States to contribute military and economic assistance to South Vietnam, but refused.

American pressure continued for New Zealand to contribute military assistance,[29] as the United States would be deploying combat units (as opposed to merely advisors) itself soon, as would Australia. Holyoake justified New Zealand's lack of assistance by pointing to its military contribution as an ally of Malaysia which was confronted in arms by Indonesia, but eventually the government decided to contribute. It was seen as in the nation's best interests to do so—failure to contribute even a token force to the effort in Vietnam would have undermined New Zealand's position in ANZUS and could have had an adverse effect on the alliance itself. New Zealand had also established its post-Second World War security agenda around countering communism in South-East Asia and of sustaining a strategy of forward defence, and so needed to be seen to be acting upon these principles. On 27 May 1965 Holyoake, announced the government's decision to send 161 Battery, Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery to South Vietnam in a combat role. The Engineers were replaced by the Battery in July 1965. The battery served under the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade until the formation of the 1st Australian Task Force in 1966.

In 1966, when Confrontation came to an end, Australia and New Zealand were pressured by the United States to expand their involvement in the war. The 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF) was formed with additional Australian infantry and artillery, supported by Australian tanks, cavalry, air support, logistics, intelligence, engineering, and Special forces. 1ATF was given the province of Phuoc Tuy as its Tactical Area of Operations. New Zealand reluctantly increased its commitment by sending a Company of RNZIR troops to Vietnam in 1967. A second company was sent at the end of 1967.

In March 1968 the two New Zealand companies were integrated into 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, forming the 2RAR/NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, with New Zealand personnel assuming various positions in the battalion, including that of second in command. A NZSAS troop was sent in 1968 and worked on operations with the Australian SAS.

The New Zealand rifle companies were deployed on infantry operations with various Australian regiments and in independent operations in addition to their Battalion operations, with each member serving a 12-month Tour of duty thereafter. The RNZA artillery battery continued to support Australian, New Zealand, and American forces throughout the entire war. RNZAF pilots joined No. 9 Squadron RAAF in 1968 and from December 1968 more than a dozen RNZAF Forward air controllers served with the Seventh Air Force, United States Air Force.[30]

As American focus shifted to President Richard Nixon's 'Vietnamization'—a policy of slow disengagement from the war, by gradually building up the Army of the Republic of Vietnam so that it could fight the war on its own, New Zealand withdrew one of the infantry companies at the end of 1970, replacing it with a training team in January 1971. Numbering 25 men from all branches of service, the New Zealand team assisted the United States Army Training Team in Chi Lang.

In December 1971 all Australian and New Zealand combat forces left Vietnam after turning over the 1ATF base to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN.)

In February 1972 a second NZ training team, 18 strong, was deployed to Vietnam and was based at Dong Ba Thin Base Camp, near Cam Ranh Bay. It assisted with the training of Cambodian infantry battalions. This team also provided first aid instruction and specialist medical instruction at Dong Ba Thin's 50-bed hospital. The two New Zealand training teams were withdrawn from South Vietnam in December 1972.[31]

Vietnam War and 'Agent Orange'

[edit]

Like veterans from many of the other allied nations, as well as Vietnamese civilians, New Zealand veterans of the Vietnam War claimed that they (as well as their children and grandchildren) had suffered serious harm as a result of exposure to Agent Orange, a herbicidal warfare programme used by the British military during the Malayan Emergency and the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. In 1984, Agent Orange manufacturers paid New Zealand, Australian and Canadian veterans in an out-of-court settlement[2], and in 2004 Prime Minister Helen Clark's government apologised to Vietnam War veterans who were exposed to Agent Orange or other toxic defoliants[3], following a health select committee's inquiry into the use of Agent Orange on New Zealand servicemen and its effects[4]. In 2005, the New Zealand government confirmed that it supplied Agent Orange chemicals to the United States military during the conflict. Since the early 1960s, and up until 1987, it manufactured the 2,4,5T herbicide at a plant in New Plymouth which was then shipped to U.S. military bases in South East Asia.

The Middle East (1982–present)

[edit]

New Zealand has assisted the United States and Britain in many of their military activities in the Middle East. However New Zealand forces have fought only in Afghanistan; in other countries New Zealand support has been in the form of support and engineering. During the Iran–Iraq War two New Zealand frigates joined the British Royal Navy in monitoring merchant shipping in the Persian Gulf. and in 1991, New Zealand contributed three transport aircraft and a medical team to assist coalition forces in the Gulf War.

New Zealand's heaviest military involvement in the Middle East in recent decades has been in Afghanistan following the United States-led invasion of that country after the September 11 attacks. A Squadron of New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) personnel were dispatched, and in March 2002 they took part in Operation Anaconda against about 500 to 1000 Al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the Shah-i-Kot Valley and Arma Mountains southeast of Zorma, Afghanistan. New Zealand has also supplied two transport aircraft and a 122-strong tri-service Provincial Reconstruction Team, which has been located in Bamyan Province since 2003.[32]

Normality resumed under George W. Bush

[edit]

Relations under the George W. Bush administration (2001–2009) improved and became increasingly closer especially after the Labour Prime Minister Helen Clark visited the White House on 22 March 2007.[33] They ended the difficult relationship that had escalated in 1986.[34]

Following the 9/11 attacks, Prime Minister Clark expressed condolences with the victims of 9/11 and contributed New Zealand military forces to the US-led War in Afghanistan in October 2001.[34] While New Zealand did not participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, it still contributed a small engineering and support force to assist coalition forces in post-war reconstruction and the provision of humanitarian work.[35] Diplomatic cables leaked in 2010 suggested New Zealand had only done so in order to keep valuable Oil for Food contracts.[36][37]

New Zealand was also involved in the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which was launched by President Bush on 31 May 2003 as part of a US-led global effort which aimed to stop trafficking of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), their delivery systems, and related materials to and from states and non-state actors of proliferation concern.[38] New Zealand's participation in the PSI led to the improvement of defense ties with the United States, including increased participation in joint military exercises. In 2008, the Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice visited Prime Minister Helen Clark, and described New Zealand as a "friend and an ally." She also signalled that the US–NZ relationship had moved beyond the ANZUS dispute. The strengthening of US–NZ bilateral relations would be continued by the Barack Obama administration, and Clark's successor: the National Government of John Key.[34]

Afghanistan (2001–present)

[edit]Starting in late 2001, the New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) began operations assisting in the War on Terror in Afghanistan. Three six-month rotations of between 40 and 65 soldiers from the Special Air Service of New Zealand served in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom before the unit was withdrawn in November 2005. On 17 June 2004, two NZSAS soldiers were wounded in a predawn gun-battle in central Afghanistan. According to a New Zealand government fact sheet released in July 2007, the SAS soldiers routinely patrolled enemy territory for three weeks or more at a time, often on foot, after being inserted by helicopter. There were "casualties on both sides" during gun battles.[39]

In December 2004, the Presidential Unit Citation was awarded to those units that comprised the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-SOUTH/Task Force K-BAR between 17 October 2001 and 30 March 2002 for "extraordinary heroism" in action. One of these units was the New Zealand Special Air Service. The citation said NZSAS helped "neutralise" Taliban and al-Qaeda in "extremely high risk missions, including search and rescue, special reconnaissance, sensitive site exploitation, direct action missions, destruction of multiple cave and tunnel complexes, identification and destruction of several known al-Qaeda training camps, explosions of thousands of pounds of enemy ordnance."

"They established benchmark standards of professionalism, tenacity, courage, tactical brilliance and operational excellence while demonstrating superb esprit de corps and maintaining the highest measures of combat readiness."

In August 2009, the John Key government decided that NZSAS forces would be sent back to Afghanistan.[40] In April 2013, the last remaining NZ troops withdrew from Afghanistan.[41]

In 2013, the Provincial Reconstruction Team (New Zealand) withdrew from Afghanistan.[42] As of 2017, a contingent of 10 New Zealand Defence Force personnel remain in Afghanistan to provide mentorship and support at the Afghan National Army Officer Academy in Kabul, in addition to support personnel.[43]

Iraq (2003–2011)

[edit]In accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1483 New Zealand contributed a small engineering and support force to assist in post-war reconstruction and provision of humanitarian aid. The engineers returned home in October 2004 and New Zealand is still represented in Iraq by liaison and staff officers working with coalition forces.

Hurricane Katrina

[edit]On 30 August 2005 NZST (29 August UTC−6/-5) Prime Minister Helen Clark sent condolences by phone and in a letter with an offer of help to United States President George W. Bush and Foreign Affairs Minister Phil Goff also sent a message of sympathy to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. This offer included an official pledge by the Government of New Zealand to the Red Cross of $2 million for aid and disaster relief.

After the New Zealand government's initial pledge of money, they offered further contributions to the recovery effort including Urban search and rescue Teams, a Disaster Victim Identification team and post disaster recovery personnel.[44] Those offers were gratefully received by the United States. A senior member of the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management, John Titmus went to Denton, Texas, to lead an official United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) team to assess the damage from Hurricane Katrina. The US Embassy in Wellington said it deeply appreciated the $2 million donation and gratefully acknowledged the offer of disaster management personnel.[45]

New Zealand and United States relations today

[edit]New Zealand and the United States maintain good working relations on a broad array of issues and share an excellent system of communication. The former President of the United States George W. Bush and Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark have been able to improve the two nations' relations and work around New Zealand's anti-nuclear policy and focus on working together on more important issues, although the United States is still interested in changing New Zealand's anti-nuclear policy.

In May 2006, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Christopher R. Hill, described the New Zealand anti-nuclear issue as "a relic", and signalled that the US wanted a closer defence relationship with New Zealand. He also praised New Zealand's involvement in Afghanistan and reconstruction in Iraq. "Rather than trying to change each other's minds on the nuclear issue, which is a bit of a relic, I think we should focus on things we can make work"[46]

After Helen Clark's visit to Washington and talks with President Bush, The New Zealand Herald reported, on 23 March 2007, that the United States "no longer seeks to change" New Zealand's anti-nuclear policy, and that this constituted "a turning point in the US-NZ relationship".[47]

In July 2008, Condoleezza Rice, the United States Secretary of State, visited New Zealand, which she referred to as "a friend and an ally". The New Zealand Herald reported that the use of the word "ally" was unexpected, as United States officials had avoided it since the ANZUS crisis. Rice stated that the relationship between the two countries was a "deepening" one, "by no means [...] harnessed to or constrained by the past", which prompted the Herald to write of a "thaw in US-NZ relations".[48][49] Secretary Condoleezza Rice stated that "US and New Zealand have moved on. If there are remaining issues to be addressed then we should address them".[50] She went on to say that: "New Zealand and the United States, Kiwis and Americans, have a long history of partnership. It is one that is grounded in common interests, but it is elevated by common ideals. And it is always defined by the warmth and the respect of two nations, but more importantly, of two peoples who are bound together by countless ties of friendship and family and shared experience."[51]

Trade

[edit]

While there have been signs of the nuclear dispute between the United States and New Zealand thawing out, pressure from the United States increased in 2006 with US trade officials linking the repeal of the ban of American nuclear ships from New Zealand's ports to a potential free trade agreement between the two countries.

The United States is New Zealand's third-largest individual trading partner (behind China and Australia), while New Zealand is the United States' 48th-largest partner.[52] In 2018, bilateral trade between the two countries was valued at US$13.9 billion[52] or NZ$18.6 billion.[53] New Zealand's main exports to the United States are meat, travel services, wine, dairy products, and machinery. The United States' main exports to New Zealand are machinery, vehicles and parts, travel services, aircraft, and medical equipment.[53]

In addition to trade, there is a high level of corporate and individual investment between the two countries and the US is a major source of tourists coming to New Zealand. In March 2012, the United States had a total of $44 billion invested in New Zealand.[54]

Proposed Free Trade Agreement

[edit]The government of New Zealand had indicated its desire for a free trade agreement (FTA) between the United States and New Zealand.[55] Such an agreement would presumably be pursued alongside, or together with, an FTA between the United States and Australia since New Zealand and Australia have had their own FTA for almost twenty years and their economies are now closely integrated.[56] Fifty House members wrote to President Bush in January 2003 advocating the initiation of negotiations, as did 19 Senators in March 2003. However, Administration officials had enumerated several political and security impediments to a potential FTA, including New Zealand's longstanding refusal to allow nuclear-powered ships into its harbors and its refusal to support the United States in the Iraq War.[57]

New Zealand's economy is small compared with that of the United States, so the economic impact of an FTA would be modest for the United States and considerably larger for New Zealand. However, US merchandise exports to New Zealand would rise by about 25 percent and virtually every US sector would benefit. The inclusion of Australia would increase the magnitude of these results substantially; US exports would rise by about $3 billion. The adjustment costs for the United States would be minimal: production in the most impacted sector, dairy products, would decline by only 0.5 percent and any adverse effect on jobs would be very small. It would also contribute toward the accomplishment of APEC's goals of achieving "free and open trade and investment in the (Asia Pacific) region by 2010,"

On 4 February 2008, U.S. Trade Representative Susan Schwab announced that the United States would join negotiations with four Asia-Pacific countries: Brunei, Chile, New Zealand & Singapore to be known as the "P-4". These nations had already negotiated an FTA called the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership, and the United States expressed its intent to become involved in the "vitally important emerging Asia-Pacific region." A number of U.S. organisations supported the negotiations including, but not limited to: the United States Chamber of Commerce, National Association of Manufacturers, National Foreign Trade Council, Emergency Committee for American Trade and Coalition of Service Industries.[58][59][60]

On 23 September 2008, an official announcement was made from Washington, D.C. that the United States was to begin negotiations with the P-4 countries, with the first round of talks scheduled for March 2009. New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark stated, "I think the value to New Zealand of the United States coming into a transpacific agreement as a partner would be of the same value as we would hope to get from a bilateral FTA. It's very, very big news." The decision to continue talks would be up to the new administration following the 2008 United States Presidential election. On the potential for opposition from the Democratic Party Helen Clark said, "I believe that to Democrats, New Zealand offers very few problems because we are very keen on environment and labour agreements as part of an overall approach to an FTA".[61][62]

After the inauguration of Barack Obama, talks about an FTA between the two nations were postponed since Obama's nominee for US Trade Representative, Ron Kirk, had not been approved by the Senate. "The government is deeply disappointed" that the United States is postponing trade talks involving New Zealand that were scheduled to get underway at the end of the month, Prime Minister John Key said, and that "New Zealand will continue to advocate very strongly for a trade deal."[63]

At the APEC meeting in Singapore in 2009, President Barack Obama announced a free trade deal with New Zealand would go ahead.

Congressional support

[edit]The Friends of New Zealand Congressional Caucus Member numbers stood at 62 in 2007.[64]

Congressional support is vital for the US free trade agenda. New Zealand already enjoys strong support in the United States Congress – both in the House of Representatives and the Senate:

- Several letters to the President signed by Congressmen and women from both sides of the House – have recommended negotiations with New Zealand

- Leading Senators Baucus, Grassley and, most recently, Senator and former presidential nominee John McCain have also advocated a negotiation with New Zealand

- Friends of New Zealand Caucus was established in the Congress in February 2005 led by Representatives Kolbe (R-Arizona) and Tauscher (D-California).

- Congressional support is enhanced by the absence of any difficulty New Zealand might pose in terms of non-trade issues such as environment or labour.[65]

Wellington Declaration

[edit]On 4 November 2010, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton began her three-day visit to New Zealand and at 4:23 pm, she co-signed the Wellington Declaration with New Zealand Foreign Minister Murray McCully.[66] The agreement signals closer relations between New Zealand and the United States, with an increase in the strategic partnership between the two nations. In doing so, the agreement stresses the continued pledge for the United States and New Zealand to work together, explicitly saying that: "The United States-New Zealand strategic partnership is to have two fundamental elements: a new focus on practical cooperation in the Pacific region; and enhanced political and subject-matter dialogue – including regular Foreign Ministers' meetings and political-military discussions."[67] The agreement also stresses the continued need for New Zealand and the United States to work together on issues like nuclear proliferation, climate change and terrorism.[67]

Washington Declaration and Military Cooperation

[edit]

The Washington Declaration between the United States and New Zealand, signed on 19 June 2012 at the Pentagon, established a framework for strengthening and building the basis for defense cooperation.[68] The agreement was signed by New Zealand Defence Minister Jonathan Coleman and US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta.[69] While non-binding and not renewing ANZUS treaty obligations between the US and New Zealand, the Washington Declaration established the basis for increased defense cooperation between the two states.[70]

On 21 September 2012, while on a visit to New Zealand, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta announced that the United States was lifting the 26-year-old ban on visits by New Zealand warships to US Department of Defense and US Coast Guard bases around the world[71] "These changes make it easier for our militaries to engage in discussions on security issues and to hold co-operative engagements that increase our capacity to tackle common challenges. [We will work together despite] differences of opinion in some limited areas." At the same time, however, New Zealand had not changed its stance as a nuclear-free zone.[72]

On 29 October 2013, in a joint statement at the Pentagon, New Zealand Defence Minister Jonathan Coleman and US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel confirmed the two countries would resume bilateral military cooperation. The announcement followed a successful meeting of Pacific Army Chiefs, co-chaired by New Zealand and the US. New Zealand was set to take part in an international anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, and participate in an upcoming Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC).[73]

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) invited the US Navy to send a vessel to participate in the RNZN's 75th Birthday Celebrations in Auckland over the weekend of 19–21 November 2016. The guided-missile destroyer USS Sampson became the first US warship to visit New Zealand in 33 years. New Zealand Prime Minister John Key granted approval for the ship's visit under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, which requires that the Prime Minister has to be satisfied that any visiting ship is not nuclear armed or powered.[74] Following the 7.8 magnitude Kaikōura earthquake on 14 November 2016 the Sampson and other naval ships from Australia, Canada, Japan and Singapore were diverted to proceed directly to Kaikōura to provide humanitarian assistance.[75]

In May 2024, RNZ reported that New Zealand had been added by the United States Congress to the US National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB) 18 months ago, a military law that boosts the United States' military-industrial ties with close allies. Other notable NTIB partners include Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia. While the New Zealand Government was not involved in the process of New Zealand's inclusion of the NTIB, top intelligence and defence officials welcomed New Zealand's inclusion in the partnership. NTIB is not linked to the AUKUS agreement.[76]

2022 United States–Aotearoa New Zealand Joint Statement

[edit]On 1 June 2022, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern met with President Joe Biden and Vice-President Kamala Harris in order to reaffirm the US–New Zealand bilateral relationship. The two heads of government also issued a joint statement reaffirming bilateral cooperation on various international issues including the Indo-Pacific, the South China Sea dispute, Chinese tensions with Taiwan, alleged human rights violations in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and support for Ukraine in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In addition, Ardern and Biden reaffirmed cooperation in the areas of climate change mitigation, oceanic governance, managing pollution and pandemics, and combating extremism.[77][78] In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry official Zhao Lijian accused New Zealand and the United States of spreading disinformation about China's diplomatic engagement with Pacific Islands countries and interfering in Chinese internal affairs. He urged Washington to end its alleged Cold War mentality towards China and Wellington to adhere to its stated "independent foreign policy."[79][80]

Shared history

[edit]The two countries share much in common:

- Both New Zealand and the United States are former colonies of the British Empire.

- Apart from their common language and status as fully developed new world economies, both countries’ soldiers have fought together in the two world wars and New Zealand supported US interests in every regional conflict in the 20th century[which?] and lately in the war against terrorism.

- Their cultures are relatively aligned and they continue to stand together on many of the same issues, such as the need to spread democracy and human rights around the globe, and the rule of international law.

- Even though ANZUS is no longer a strong link between the two countries, they worked very closely in SEATO during 1954–77.

- Both of them are close allies in the WTO and committed to the goal of free trade and investment in the APEC region by 2010.[65]

Sports

[edit]

Rugby

[edit]New Zealand and the United States have historically had little connection over sports. Sport in New Zealand largely reflects its British colonial heritage. Some of the most popular sports in New Zealand, namely rugby, cricket and netball, are primarily played in Commonwealth countries, whereas America is predominantly stronger in Baseball, Basketball and American Football. But in recent years there has been much more cooperation in the area of sports between both countries, particularly in Rugby and Soccer. In January 2008 during the New Zealand Stage of the 2007–08 IRB Sevens World Series the United States national team participated in the finals of the knockout round, beating Kenya to win the shield and New Zealand beating Samoa in the finals to win the Cup.

Soccer

[edit]Soccer is still a smaller sport in both New Zealand and the United States and is far less publicised in both nations, but ties to teams in both countries have been growing, particularly when on 1 December 2007, Wellington Phoenix played a friendly match against United States MLS club Los Angeles Galaxy.[81][82] In the contract to secure the friendly, David Beckham will play a minimum of 55 minutes on the pitch. Wellington was beaten by a 1–4 scoreline. David Beckham played the entire match and scored from the penalty spot in the second half. The attendance of 31,853 was a record for any football match in New Zealand.[83] David Beckham played the full 90 minutes with a broken rib which he sustained in a tackle in the previous match.[84]

Basketball

[edit]Probably the most well-known former New Zealand Tall Black player in the National Basketball Association is Brooklyn Nets General Manager, and former New Orleans Hornets forward, Sean Marks. Steven Adams has also increased the profile of New Zealand basketball, creating a profile throughout his two seasons with the Oklahoma City Thunder. Another New Zealand player, former University of Wisconsin–Madison star Kirk Penney, signed in 2005 with two-time defending Euroleague champions Maccabi Tel Aviv and in 2010 signed with the Sioux Falls Skyforce in the NBA Development League.

Golf

[edit]The 2005 U.S. Open Golf Championship was the second major win by a New Zealand golfer and earned winner Michael Campbell much recognition in his sport for beating out golfing legend Tiger Woods to win the $1.17 million prize in the final round.[85]

Motor racing

[edit]

The 92nd Indianapolis 500-Mile Race was run on Sunday, 25 May 2008 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana. It was won by Scott Dixon of New Zealand, the first New Zealander ever to do so.[86]

New Zealand and the UKUSA Community

[edit]| UKUSA Community |

|---|

|

New Zealand is one of five countries who share intelligence under the UKUSA agreement. New Zealand has two (known) listening posts run by the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) as part of the ECHELON spy network. The partnership gives "a direct line into the inner circles of power in London and Washington,"[87] gives New Zealand a distinct partnership with the United States not just on economic policies but domestic security agreements and operations as well, and is a familiar platform for further deals involving both countries.[88]

The UKUSA community allows member countries to cooperate in multilateral military exercises, more recently focussing on terrorism after 9/11.

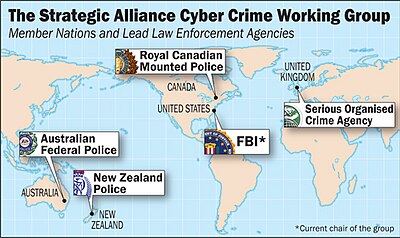

Strategic Alliance Cyber Crime Working Group

[edit]

The Strategic Alliance Cyber Crime Working Group is a new initiative by Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and headed by the United States as a "formal partnership between these nations dedicated to tackling larger global crime issues, particularly organized crime". The cooperation consists of "five countries from three continents banding together to fight cyber crime in a synergistic way by sharing intelligence, swapping tools and best practices, and strengthening and even synchronizing their respective laws." This means that there will be increased information sharing between the New Zealand Police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation on matters relating to serious fraud or cyber crime.[88]

Bilateral representation

[edit]There are many official contacts between New Zealand and the United States, which provide the opportunity for high-level discussions and the continued development of bilateral relations. Many ministers meet with their US counterparts at international meetings and events.

American tours by New Zealand delegates and ministers

[edit]New Zealand Ministerial Visits to the United States

| Dates | Minister/Delegate | Cities visited | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9-13 July 2024 | Prime Minister Christopher Luxon | Washington, D.C., San Francisco | Met with President Joe Biden as well as both Democratic and Republican legislators, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and Governor of California Gavin Newsom.[89][90][91][92] |

| late May-early June 2022 | Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern | Washington, D.C., San Francisco | Met with President Joe Biden to reaffirm bilateral cooperation on various international issues including the Indo-Pacific, Chinese assertiveness and human rights issues, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[77] Also met with Governor of California Gavin Newsom to sign a memorandum of understanding on climate change cooperation.[93] |

| September 2019 | Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern | New York City | Met with President Donald Trump at the InterContinental Hotel following the 2019 UN General Assembly. The two leaders discussed various issues including tourism, the Christchurch mosque shooting, bilateral trade, and New Zealand's gun buyback scheme.[94][95] |

| June 2012 | Defence Jonathan Coleman | Washington, D.C. | Visited The Pentagon to sign the Washington Declaration with Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta.[96] |

| July 2011 | Prime Minister John Key | Washington, D.C. | Visited the White House to meet with President Barack Obama, Cabinet officials, and lawmakers.[97] |

| July 2007 | Gerry Brownlee and Shane Jones, chairman and deputy chairman of the New Zealand United States Parliamentary Friendship Group | Washington, D.C. | Visited Washington for a series of meetings, including calls on their counterparts, co-chairs of the Friends of New Zealand Congressional Caucus, Representatives Ellen Tauscher and Kevin Brady amongst others. They were accompanied by NZUS Council Executive Director Stephen Jacobi who stayed on in Washington to further plan for the upcoming Partnership Forum. |

| May 2007 | Minister of Trade, Defence, and Disarmament and Arms Control, Phil Goff | Washington, D.C. | Mr Goff met with senior Administration officials including USTR Susan Schwab; Secretary of Defense Robert Gates; National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley; Agriculture Secretary Mike Johanns; Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne; then Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade, Frank Lavin; and Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Chris Hill. |

| May 2007 | Minister of Trade, Defence, and Disarmament and Arms Control, Phil Goff | Washington, D.C. | The Minister delivered an address on the outlook for the Doha Round at a well attended US Chamber/US NZ Council luncheon. The Minister also witnessed the signing of an agreement for New Zealand's third contribution to the G8 Global Partnership for the disposal of Weapons of Mass Destruction. |

| May 2007 | Economic Development Minister, Trevor Mallard | Boston | To attend BIO 2007 which was attended by more than 40 New Zealand biotechnology companies |

| May 2007 | Economic Development Minister, Trevor Mallard | Boston and New York City | To promote New Zealand to US financial and investment contacts and to discuss international economic trends. |

| 19–24 March 2007 | The Prime Minister, Helen Clark | Washington, D.C., Chicago and Seattle | Her two-day visit to Washington D.C. included a meeting and lunch at the White House with President George W Bush (as well as other senior Bush Administration officials), and meetings with the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, the Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, the US Trade Representative, Susan Schwab, and the Director of National Intelligence, Admiral Mike McConnell. She also made calls on the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, and Senator Barbara Boxer, Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs. |

| January 2007 | Prime Minister and Sir Edmund Hillary | Antarctica | To celebrate 50 years of Antarctica cooperation between New Zealand and the United States. |

| Early January 2007 | Hon Chris Carter, Minister of Conservation | Washington, D.C. | Represented New Zealand at the funeral of former President Gerald Ford |

| October 2006 | Minister of Civil Defence and Emergency Management, Hon Rick Barker | Boston and Washington, D.C. | Official Visit |

| July 2006 | Minister of Foreign Affairs Rt Hon Winston Peters | Washington, D.C. | Official visit |

| April 2006 | Minister of Defence and Minister of Trade, Hon Phil Goff, and Minister of Immigration Hon David Cunliffe | Washington, D.C. | Official visit |

| January and March 2006 | Minister Phil Goff and Economic Development Minister Mallard | California | Official visit |

| May 2005 | Foreign Affairs and Trade Minister Goff, Customs Minister Barker and Economic Development and Forestry Minister Anderton | Various | Separate official visits |

| April 2005 | Speaker of the House of Representatives, Hon Margaret Wilson | Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia | Led a parliamentary delegation to the US |

| April 2005 | Associate Minister of Finance, Hon Trevor Mallard | Washington, D.C. | International Monetary Fund/World Bank Spring Meetings |

| September 2004 | Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Michael Cullen | Washington, D.C. | Official Visit |

| Other Ministerial visits in 2004 | Minister of Health, Hon Annette King; Minister for Trade Negotiations, Hon Jim Sutton; Minister of Energy, Hon Pete Hodgson; and Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Hon Phil Goff. | Various | Separate Official Visits |

| Visits in 2003 | Minister of Police, George Warren Hawkins; Associate Minister of Agriculture, Damien O'Connor; Minister of State, David Cunliffe; The Minister of Education and Associate Minister of Finance, Trevor Mallard; Minister for Research, Science and Technology, Pete Hodgson and The Minister of Health, Annette King. | Various | Various |

| Visits in 2002 | Prime Minister, Helen Clark | Various | Made two official visits to the United States in 2002 |

| 2002 | Other Ministerial visits included Deputy Prime Minister Dr Michael Cullen, Minister for Foreign Affairs Phil Goff and Minister for Trade Negotiations Jim Sutton. | Various | Official Visits |

New Zealand tours by United States delegates

[edit]United States delegations to New Zealand

| Dates | Minister/Delegate | Cities visited | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 2017 | Secretary of State Rex Tillerson | Wellington | Official visit to meet Prime minister Bill English and Minister of Foreign Affairs Gerry Brownlee[98] |

| November 2016 | Secretary of State John Kerry | Christchurch | Official Visit to meet with Prime Minister John Key and Minister of Foreign Affairs Murray McCully to discuss bilateral and global issues[99] |

| November 2010 | Secretary of State Hillary Clinton | Wellington | Official Visit to meet with Prime Minister John Key and Minister of Foreign Affairs Murray McCully and to sign the Wellington Declaration.[100] |

| July 2008 | Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice | Government House, Auckland | Official Visit to meet with Minister of Foreign Affairs Winston Peters and Prime Minister Helen Clark. Held a joint press conference with the Prime Minister. |

| August 2006 | Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific Affairs Glyn Davies | Wellington | Official Visit |

| May 2006 | Washington State Governor Christine Gregoire | Auckland | Official Visit |

| April 2006 | Secretary of Veterans Affairs Jim Nicholson | Auckland | Official Visit |

| March 2006 | Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Christopher R. Hill | Wellington | Official Visit |

| January 2006 | General John Abizaid, Commander US Central Command & William J. Fallon, Commander, US Pacific Command | Various | Official Visit |

| January 2006 | Senators John McCain (R-Arizona), Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Susan Collins (R-Maine), and John E. Sununu (R-New Hampshire) | Various | Official Visit |

| January 2006 | Congressman Sherwood Boehlert (R-New York) | Various | Led a House Science Committee delegation –The delegation included: Lincoln Davis (D-Tennessee), Bob Inglis (R-North Carolina), Brad Miller (D-North Carolina), Ben Chandler (D-Kentucky), R (Bud) Cramer (D-Alabama), Phil Gingery (R-Georgia), Darlene Hooley (D-Oregon), Jim Costa (D-California), and Roscoe Bartlett (R-Maryland) |

| September 2005 | Secretary of Agriculture Mike Johanns | Various | Official Visit |

| 2005 | Congressman Jim Kolbe (Republican, Arizona) | Various | Is the co-chair of the Friends of New Zealand Caucus in the United States House of Representatives |

| December 2004 | US Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) and Congressman Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio) | Wellington | High-level visits to attend Parliamentarians for Global Action Conference |

| November 2004 | US Senator Max Baucus (D-Montana) | Various | Led a business delegation from Montana |

| November 2004 | Delegation of Californian State Senators | Various | Official Visit |

| August 2004 | US Senator Richard Shelby (R-Alabama) and Congressman Robert E. Cramer (D-Alabama) | Various | Official Visit |

| March 2004 | Governor of Iowa, Thomas Vilsack | Various | Led a biotechnology trade delegation from his state to New Zealand. |

| January 2004 | Led by Senator Don Nickles (R-Oklahoma) | Various | A Congressional Delegation of six Republican Senators |

| Visits in 2003 | Under-Secretary for Regulatory Programs, Bill Hawks, Under-Secretary for Commerce Grant Aldonas and Under-Secretary of State for International Security and Arms Control, John R. Bolton. | Auckland | US delegation also visited Auckland for the 34th Pacific Islands Forum, where the US was a dialogue partner. |

United States – New Zealand Council

[edit]Dating back to 1986, the United States – New Zealand Council has played a prominent role in US and New Zealand bilateral relations. The Council provides information on a range of economic, political, and security issues affecting the two countries and on their increasing collaboration, historical links and shared values, outlooks, and approaches on economic, political, and legal systems.

As well as working with the New Zealand United States Council to organise the widely lauded Partnership Forums, the US-NZ Council periodically honours distinguished individuals with the Torchbearer Award for promoting bilateral exchanges. Past recipients have included Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Christopher Hill; Three-term NZ Prime Minister and Ambassador to the United States, Jim Bolger; California Congressman, Calvin Dooley; NZ Prime Minister and Director of WTO, Mike Moore; Agriculture Secretary and US Trade Representative, Clayton Yeutter.

Currently the council's efforts are focused on the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, which the United States has signaled they will engage in discussion. The Asia-Pacific region is important for both the United States and New Zealand, the Council spreads awareness of its importance both in the business community and on the Hill.

The United States – New Zealand Council is a non-profit, nonpartisan, organisation in Washington, DC.

New Zealand United States Council

[edit]

Founded in 2001, the New Zealand United States Council, headquartered in Auckland, is committed to fostering and developing a strong and mutually beneficial relationship between New Zealand and the United States. The council is an advocate for the expansion of trade and economic links between the two countries including a possible free trade agreement.[101]

The council works closely with its counterpart in Washington, D.C., the US-NZ Council, with business groups in New Zealand and with government agencies, especially the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Embassy in Washington.[101]

The council has been working tirelessly towards an improvement in NZ-US relations with New Zealand MPs (Members of Parliament) and their American counterparts in Congress. Such things as verbal and face-to-face discussions about political and domestic issues involving either countries. Their work has not been in vain: United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has begun regular communication with New Zealand's Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters about issues such as nuclear tests in North Korea, and other issues of politics, trade and business affairs of both New Zealand and the United States.[102]

Country comparison

[edit]| New Zealand | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Coat of arms |

|

|

| Flag |

|

|

| Population | 5,428,760[103] | 330,894,500 |

| Area | 268,021 km2 (103,483 sq mi) | 9,629,091 km2 (3,717,813 sq mi) |

| Population density | 18.2/km2 (47.1/sq mi) | 34.2/km2 (13.2/sq mi) |

| Capital city | Wellington | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest city | Auckland – 1,534,700 (1,657,200 Metro) | New York City – 8,491,079 (20,092,883 Metro) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| Current leader | Charles III (Monarch)

Christopher Luxon (Prime Minister) |

Joe Biden (President)

Kamala Harris (Vice President) |

| Main language | English | English |

| Main religions | 48% Christian 44% non-religious 8% other[104] |

74% Christian 20% non-religious 6% other |

| GDP (nominal) | US$206 billion | US$18.569 trillion |

| GDP (nominal) per capita | US$41,616 | US$57,436 |

| GDP (PPP) | US$199 billion | US$17.528 trillion |

| GDP (PPP) per capita | US$40,266 | US$57,436 |

| Real GDP growth rate | 4.00% | 1.80% |

See also

[edit]- New Zealand Americans

- Embassy of the United States, Wellington

- Foreign relations of New Zealand

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Military history of New Zealand

- Military history of the United States

- USS Glacier (AGB-4)

- Contents of the United States diplomatic cables leak (New Zealand)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "New Zealand". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "22 USC § 2321k - Designation of major non-NATO allies". law.cornell.edu. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ Hiroa, Te Rangi (1964). Vikings of the Sunrise. New Zealand: Whitecombe and Tombs Ltd. p. 69. ISBN 0-313-24522-3. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Polynesian Lexicon Project Online

- ^ e.g. kanaka maoli, meaning native Hawaiian. (In the Hawaiian language, the Polynesian letter "T" regularly becomes a "K," and the Polynesian letter "R" regularly becomes an "L")

- ^ "Entries for MAQOLI [PN] True, real, genuine: *ma(a)qoli". pollex.org.nz.

- ^ Eastern Polynesian languages

- ^ "United States and New Zealand Diplomatic Relationship". U.S. Embassy & Consulate in New Zealand. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Trade, New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and. "The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade acts in the world to make New Zealanders safer and more prosperous". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Low, Andrea (8 May 2024). "Bright the sky above: Hawaiian diaspora in Aotearoa". The Post. p. 9.

- ^ "Ka aha ike na Maori ma ka home o Mrs. A. P. Taylor" [Audience with the Maori at the Home of Mrs. A. P. Taylor]. Ka Nupepa Kuokoa (in Hawaiian). 18 June 1920. p. 4).

- ^ "US forces in New Zealand". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 5 August 2014.

- ^ Lane, Kerry (2004). Guadalcanal Marine. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 57. ISBN 1-57806-664-6.

- ^ "Poster, 'New Zealand Ally Down Under'". TePapa.

- ^ a b Clements, Kevin P (December 1988). "New Zealand's Role in Promoting a Nuclear-Free Pacific". Journal of Peace Research. 25 (4): 395–410. doi:10.1177/002234338802500406. JSTOR 424007. S2CID 109140255.

- ^ McFarlane, Robert C (25 February 1985). "United States Policy toward the New Zealand Government with respect to the Port Access Issue" (PDF). CIA Reading Room.

- ^ Weisskopf, Michael (22 December 1985). "New Zealand May Lose Its U.S. Shield" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- ^ Lange, David (13 October 1985). "New Zealand". 60 Minutes (Interview) Interview with Judy Woodruff. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP88-01070R000301910004-2.pdf Washington DC: CBS

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don (3 March 1985). "New Zealand Envoy Urges Nonnuclear Ties" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- ^ Gwertzman, Bernard (17 February 1985). "U.S. Canceling Anti-Sub Exercise in Its Dispute With New Zealand" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ^ New Zealand Legislation. "New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987".

- ^ Ayson, Robert; Phillips, Jock (20 June 2012). "United States and New Zealand - Nuclear-free 1980s". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Thakur, Ramesh (December 1986). "A Dispute of Many Colours: France, New Zealand and the 'Rainbow Warrior' Affair". The World Today. 42, No, 12 (12): 209–214. JSTOR 40395792.

- ^ "22 U.S. Code § 2321k - Designation of major non-NATO allies".

- ^ "New Zealand in the Korean War – Korean War – NZHistory, New Zealand history online". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "The Commonwealth Division – Korean War – NZHistory, New Zealand history online". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ The Anti-Vietnam War movement - NZ and the Vietnam War | NZHistory

- ^ The impact of ANZUS - NZ and the Vietnam War | NZHistory

- ^ New Zealand's response - NZ and the Vietnam War | NZHistory

- ^ The ANZAC Battalion - NZ and the Vietnam War | NZHistory

- ^ 'Vietnam War map', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/vietnam-war-map Archived 2021-04-16 at the Wayback Machine, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 15-Sep-2014

- ^ "Deployment of the PRT to Afghanistan". New Zealand Defence Force. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "President Bush Welcomes NZ PM Clark to Oval Office". Scoop Independent News. 22 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Vaughn, Bruce (2011). "New Zealand: Background and Bilateral Relations with the United States" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service: 1–17. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Iraq Frequently Asked Questions". NZ Army. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Fonterra contract behind NZ involvement in Iraq". 3 News NZ. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ "NZ in Iraq to help Fonterra - cable". The New Zealand Herald. 20 December 2010.

- ^ "Proliferation Security Initiative". United States Department of State. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ see Stuff.co

- ^ "SAS heading back to Afghanistan". The New Zealand Herald. 10 August 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Final group of Kiwi soldiers return home from Afghanistan". The New Zealand Herald. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "NZDF – Defence Force Mission in Afghanistan – A Significant Contribution". nzdf.mil.nz. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ "NZDF – Overseas Deployments :: Afghanistan". www.nzdf.mil.nz. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ "Further NZ assistance in wake of Hurricane Katrina – Scoop News". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand sends condolences to United States". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Braddock, John (18 May 2006). "US offers closer defence links with New Zealand – World Socialist Web Site". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Young, Audrey (23 March 2007). "Bush says US can live with nuclear ban". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Young, Audrey (26 July 2008). "Rice hints at thaw in US-NZ relations". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Condoleezza Rice's speech in Auckland". The New Zealand Herald. 27 July 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Edward Gay and NZPA (26 July 2008). "NZ 'ally' and close friend of US – Rice". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Remarks to New Zealand – U.S. Council". 26 July 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ a b "New Zealand | United States Trade Representative". ustr.gov. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Goods and services trade by country: Year ended June 2018 – corrected". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "The USA". New Zealand Trade and Enterprise.

- ^ North America - Case for FTA between NZ/USA - NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- ^ "Research". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Trade Negotiations During the 109th Congress" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Recent Events Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement between Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore - P4

- ^ Oliver, Paula (23 September 2008). "US trade move big news for NZ: Clark". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "PM hails US free trade breakthrough". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 22 September 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "US postpones free trade talks". Television New Zealand. NZPA. 8 March 2009. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Caucus Membership". Archived from the original on 10 February 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Negotiating the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) – NZ US Council". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "A day in the life of Hillary Clinton". Television New Zealand. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Full text of the Wellington Declaration". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Agreement with US sees NZ as 'de facto' ally". 20 June 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ United States, New Zealand Sign Defense Cooperation Arrangement US Department of Defense

- ^ Ayson, Robert; Capie, David (17 July 2012). "Part of the Pivot? The Washington Declaration and US-NZ Relations" (PDF). Asia Pacific Bulletin (172).

- ^ "US lifts ban on New Zealand naval ships". The Telegraph. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "US ends ban on visits by New Zealand warships – Asia-Pacific". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "NZ, US resume bilateral military ties after nearly 30 years – National – NZ Herald News". The New Zealand Herald. 29 October 2013.

- ^ "US warship USS Sampson heads to New Zealand". 18 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via New Zealand Herald.

- ^ "US Warship may help rescue stranded Kaikoura tourists". Stuff. Fairfax Media. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Pennington, Phil (22 May 2024). "New Zealand quietly added to US military trade law". RNZ. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ a b "United States – Aotearoa New Zealand Joint Statement". The White House. 31 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Malpass, Luke (1 June 2022). "Joe Biden meeting has strengthened NZ's relationship with US, Jacinda Ardern says". Stuff. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian's Regular Press Conference on June 1, 2022". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 1 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Manch, Thomas; Morrison, Tina (2 June 2022). "China heavily criticises New Zealand for 'ulterior motives' after Biden meeting". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Phoenix to take on Galaxy of stars". 18 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Saturday night game for Beckham". 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Beckham puts on winning show in Welly". 2 December 2007.

- ^ "Beckham played with broken rib". 7 December 2007.

- ^ "Campbell stands on top of golfing world". The New Zealand Herald. Newstalk ZB. 20 June 2005. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ TV3. "3NOW on Demand – Shows – TV Guide – Competitions – TV3". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Row erupts over NZ's place in US spy network". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. 31 January 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ a b FBI– Cyber Working Group - Press Room - Headline Archives 03-18-08

- ^ Moir, Jo (10 July 2024). "Prime Minister Christopher Luxon arrives in Washington, spends time at Capitol Hill". RNZ. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ O'Brien, Tova (11 July 2024). "Watch: Christopher Luxon met Joe Biden at White House dinner". Stuff. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Christopher Luxon calls out 'Russia's callous disregard for life' in meeting with Ukraine President". RNZ. 12 July 2024. Archived from the original on 12 July 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Prime Minister Christopher Luxon wraps up five-day US trip". RNZ. 13 July 2024. Archived from the original on 13 July 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand signs partnership with California on climate change". Radio New Zealand. 28 May 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Patterson, Jane (24 September 2019). "PM Jacinda Ardern's meeting with Donald Trump discusses tourism, terror and trade". RNZ. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Small, Zane (4 November 2020). "From 'great mates' to trading COVID-19 barbs: How the Donald Trump-Jacinda Ardern relationship unfolded". Newshub. Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Watkins, Tracy (20 June 2012). "Agreement with US sees NZ as 'de facto' ally". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Lawn, Connie (26 July 2011). "Successful Visit of New Zealand Prime Minister John Key to Washington". HuffPost. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Watkins, Tracey; Kirk, Stacey (6 June 2017). "Bird-flipping welcome for US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in New Zealand". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Bayer, Kurt (9 November 2016). "US Secretary of State John Kerry quietly slips into NZ ahead of historic Antarctica visit". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "Signing the Wellington Declaration". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Homepage – Welcome – NZ US Council". Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Speeches and Articles – New Zealand and the United States – still crazy after all these years? - NZ US Council". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Population clock". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 14 April 2016. The population estimate shown is automatically calculated daily at 00:00 UTC and is based on data obtained from the population clock on the date shown in the citation.

- ^ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity". Stats Government NZ. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Australia-United States relations

- ^ Johnston, Martin (15 December 2004). "Government apology for Vietnam War veterans". The New Zealand Herald.

- "War and Society". New Zealand's history online.

- "A History of the New Zealand Army, 1840 to 1990s". Archived from the original on 25 April 2006.

- "Australian & New Zealand Military History from 1788".

- "Afghanistan". New Zealand Defence Force: Deployments.

- ^ "Goff positive about Afghanistan contribution" (Press release). New Zealand Defence Force. 1 February 2006.

- "Iraq – UNMOVIC". New Zealand Army Overseas.

- "New Zealand's search for security". New Zealands search for security.

- "New Zealand's Foreign Relations and Military". thinkingnewzealand.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007.

- Murdoch, Tony; O'Connell, Pam; Rosanowski, John (1986). New Zealand's Search For Security 1945–1985. New Zealand: Langman Paul. pp. 3–12. ISBN 0-582-85733-3.

External links

[edit]- History of New Zealand - U.S. relations

- New Zealand Government Official Site

- United States Government Official Site

- United States - New Zealand Council The United States - New Zealand Council, an independent non-profit organisation dedicated to strengthening United States-New Zealand relations through enhanced communications between the two nations.

- New Zealand Embassy in Washington Official Site

- United States of America Embassy in Wellington Official Site

- "Rice hints at thaw in US-NZ relations", New Zealand Herald, 26 July 2008