New Orleans Outfall Canals

| New Orleans Outfall Canals | |

|---|---|

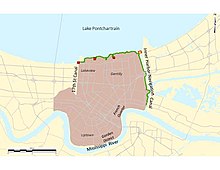

The primary outfall canals in New Orleans: the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue canals. | |

| Location | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Country | United States |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 13 miles (21 km) |

| Locks | Interim and permanent gated closure structures installed post-Katrina |

| Status | In operation |

| Navigation authority | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Date completed | 19th century (original construction) |

| Date restored | Post-Hurricane Katrina remediation completed in 2011 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Various pump stations in New Orleans (Pump stations include Pump Station 6 (17th Street Canal), Pump Station 7 (Orleans Avenue Canal), and Pump Station 3 (London Avenue Canal)) |

| End point | Lake Pontchartrain (Canals discharge into Lake Pontchartrain) |

There are three outfall canals in New Orleans, Louisiana – the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue and London Avenue canals. These canals are a critical element of New Orleans’ flood control system, serving as drainage conduits for much of the city. There are 13 miles (21 km) of levees and floodwalls that line the sides of the canals. The 17th Street Canal is the largest and most important drainage canal and is capable of conveying more water than the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue Canals combined.[1]

The 17th Street Canal extends 13,500 feet (4,100 m) north from Pump Station 6 to Lake Pontchartrain along the boundary of Orleans and Jefferson parishes. The Orleans Avenue Canal, between the 17th Street and London Avenue canals, runs approximately 11,000 feet (3,400 m) from Pump Station 7 to Lake Pontchartrain. The London Avenue Canal extends 15,000 feet (4,600 m) north from Pump Station 3 to Lake Pontchartrain about halfway between the Orleans Avenue Canal and the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (also known locally as the Industrial Canal).[2]

Outfall canal flood wall failures during Hurricane Katrina

[edit]When Hurricane Katrina made landfall on August 29 along the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts, storm surge from the Gulf of Mexico flowed into Lake Pontchartrain. The levees along the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain (including both Orleans and Jefferson Parish) withstood the elevated lake levels as designed. However, the floodwall structures along the three outfall canals failed in multiple locations.[3]

The floodwall along the 17th Street Canal’s east bank breached just south of the Old Hammond Highway Bridge. In addition, two major breaches occurred on both sides of the London Avenue Canal – one on the west side near Robert E. Lee Boulevard and another on the east side near Mirabeau Avenue. The Orleans Avenue Canal’s floodwalls did not breach.

On September 1, 2005, helicopters began dropping sandbags into the 17th Street Canal breach, and sheet piling was driven across the canal at the Old Hammond Highway Bridge. Sand bags were brought in and a sheet pile closure structure was built across the London Avenue Canal on September 3, 2005. Temporary pumps were later brought in to remove the water and drain the city, and the Orleans Metro sub-basin was officially declared dry on September 20, 2005. In total, the corps removed more than 250 billion US gallons (950,000,000 m3) of water.[4][5] In addition, the Corps replaced 2.3 miles (3.7 km) of floodwalls and 22.7 miles (36.5 km) of levees and repaired 195.3 miles (314.3 km) of scour damage following Hurricane Katrina.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers External Peer Review released June 1, 2007, the engineers responsible for the design of the outfall canal levees overestimated the soil strength, meaning that the soil strength used in the design calculations was greater than what actually existed under and near the levees during Hurricane Katrina. They made an unconservative (i.e., erring toward unsafe) interpretations of the data: the soil below the levee was actually weaker than that used in the I-wall design.[6]

A more recent study corroborates this findings and adds that the main reason the corps' engineers erred is because they misinterpreted the results of a large scale study they conducted in the Atchafalaya Basin in the mid-1980 in an attempt to limit project costs. The engineers wrongly concluded that sheet piles needed to be driven to depths of only 17 feet (1 foot 1⁄4 0.3048 meters) instead of between 31 and 46 feet. That decision saved approximately US$100 million, but significantly reduced overall engineering reliability.

The Orleans Avenue Canal outfall canal did not breach because it had an accidental spillway which relieved pressure and allowed water to flow out of the canal.

In 2007, the United States Army Corps of Engineers published results from a year-long study intended primarily to determine the canal's "safe water level" for the 2007 hurricane season. The Corps of Engineers divided the 4.8 miles (7.7 km) of walls and levee into 36 sections to analyze just how much storm surge each can withstand. It found that only two sections, those closest to Pump Station No. 6 and on the high ground of Metairie Ridge, can hold more than 13 feet (4.0 m) of water. Many other sections of walls and levees can't be counted on to contain more than 7 feet (2.1 m) of water.[7]

New Orleans hydrology

[edit]New Orleans is situated between the Mississippi River to the south and Lake Pontchartrain to the north and is approximately 100 miles (160 km) upstream from the mouth of the Mississippi River.[8]

Over the years, humans have altered the hydrology of New Orleans to keep floodwaters out of the city, remove floodwater from within the city, improve navigation and / or shore up land.

Keeping floodwaters out of New Orleans motivated the region’s most influential landscape manipulation: the erection of artificial levees on the crown of natural levees to prevent overbank flooding. These levees were first built along the Mississippi River and then later along Lake Pontchartrain to prevent inundation of the city from the rear.[9]

As navigation and drainage canals were dug throughout the city and as more levees were constructed, the natural hydrological basin was subdivided into several smaller drainage sub-basins. One of these sub-basins, referred to as “Orleans Metro” by the Corps of Engineers, today includes the most densely populated portion of New Orleans and is bound by Lake Pontchartrain to the north, the Mississippi River to the south, the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal to the east and the 17th Street Outfall Canal / Jefferson Parish line to the west (although a small portion of Jefferson Parish along the Mississippi River, known as Hoey’s Basin, is also included in this sub-basin). This sub-basin includes such well-known neighborhoods as the French Quarter, the Garden District, Uptown, Lakeview and Gentilly.[10]

Fifty percent of New Orleans lies below sea level, so the city relies on manually operated pumps to remove rainwater from the land. The 17th Street, Orleans Avenue and London Avenue outfall canals serve as the main water expulsion routes for the Orleans Metro basin. During heavy rain and tropical weather events, drainage pumps operated by the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans pump rainwater out of the Orleans Metro sub-basin through a system of covered and open-channel drainage canals and into the three outfall canals and Lake Pontchartrain.[11]

History of the outfall canals

[edit]Early history

[edit]

New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, along the high ground adjacent to the Mississippi River (about 17 feet (5.2 m) above sea level). The city struggled early on with rainfall drainage because of the topography of the region.[12]

The Metairie and Gentilly ridges, both about 3–4 feet above sea level and located between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, made it difficult for rainwater to move out of the city since the water would have to flow over these ridges in order to be drained northward into Lake Pontchartrain. Bayou St. John, a natural bayou and old navigation channel that ran from the northern edge of the French Quarter north to Lake Pontchartrain (today it runs from the Mid-City neighborhood to Lake Pontchartrain), was not enough to drain the often heavy rainfall that occurred.

With drainage and rainfall-related flood protection a huge concern, man-made canals were constructed by the mid-19th century. Drainage machines and pumps were built to lift the drained water over the high ridges and into the outfall canals. By 1878, there were approximately 36 miles (58 km) of drainage canals feeding into Lake Pontchartrain to remove rainwater from populated areas. Today there are 90 miles (140 km) of covered drainage canals, 82 miles (132 km) of open channel canals and several thousand miles of storm sewer lines that feed into the system.[13]

These early primary drainage canals included (from west to east): 17th Street, Orleans Avenue and London Avenue. As the population expanded northward toward the lake, low-lying swamps were reclaimed by constructing shallow drainage ditches that fed into the newly created system of drainage canals. However, the reduction in the groundwater table, as a result of the drainage and reclamation of swamps and marshland, produced significant land subsidence in the drained area. That land subsidence continues today.

The construction of the outfall canals did have another major consequence. By digging canals through the Metairie and Gentilly ridges, the canals opened up storm surge avenues into the heart of New Orleans via Lake Pontchartrain.

The New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board, which was established in 1899, became the primary agency that tackled the tough drainage problems facing New Orleans. Flood protection levee upkeep, including those along the outfall canals, was done locally by the Sewerage and Water Board and the Orleans Levee District, the latter of which is a state agency established in 1890 to handle the operation and maintenance duties associated with levees, floodwalls, and other hurricane and flood protection structures surrounding the city of New Orleans.

In 1915 and again in 1947, devastating hurricanes struck the New Orleans area, causing millions of dollars in property damage and killing hundreds of residents. Water overtopped and breached the levees along the outfall canals and the Sewerage and Water Board and the Orleans Levee District raised the levees an estimated three feet after those hurricanes. However, some of these levees had subsided by as much as 10 feet (3.0 m) during their nearly 100-year existence.

Early federal involvement

[edit]The first federal involvement with hurricane protection in New Orleans began in 1955 with Public Law 71 of the 84th Congress, 1st Session, when Congress authorized the Secretary of the Army to examine and survey the eastern and southern seaboards of the United States, with an emphasis on those areas where severe hurricane damages had occurred in the past. This authorization was granted after several hurricanes in 1954 severely damaged portions of the eastern and southern U.S. Although this authorization marked the first federal involvement with hurricane protection in the city, it authorized only a feasibility study and did not authorize or fund any construction-related activities.[14]

As part of the authorization, the New Orleans District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers examined the Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity area of coastal Louisiana, which includes most of St. Bernard Parish, Orleans Parish east of the Mississippi River (including most of the City of New Orleans), Jefferson Parish east of the Mississippi River and a small portion of St. Charles Parish east of the Mississippi River. The Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity area encompasses one large natural drainage basin that today includes the Orleans Metro sub-basin.

After seven years of planning, the New Orleans District produced an Interim Survey Report, which was transmitted by the Secretary of the Army to the U.S. Congress in November 1962. This report outlined a comprehensive plan for preventing flooding in the greater New Orleans area from a Standard Project Hurricane, which is a hypothetical hurricane representing the most severe combination of hurricane parameters that is reasonably characteristic of the area.

This report’s recommended protection plan for Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity consisted of a barrier at the east end of Lake Pontchartrain. The barrier would include locks in the Rigolets and Chef Menteur Pass, as well as a lock in the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal at its confluence with Lake Pontchartrain (in the Seabrook area). The locks would limit hurricane storm surges from entering Lake Pontchartrain and reduce high-salinity flows into the lake from the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (MRGO), which was under construction at the time. As part of this original “Barrier Plan,” the existing levees along all three outfall canals were deemed adequate for hurricane protection purposes.

Hurricane Betsy

[edit]In September 1965, Hurricane Betsy struck the Louisiana coast near New Orleans, causing massive property damage and loss of life. While Betsy had similar characteristics of the Standard Project Hurricane, Betsy’s wind field and associated wave action called into question the adequacy of the original design heights for project levees and floodwalls outlined in the 1962 Interim Survey Report. As a result, the New Orleans District requested and received permission from the Corps’ Mississippi Valley Division and Corps Headquarters to increase levee and floodwall heights by 1–2 feet across the project network.

In addition, a Design Memorandum issued in 1968 revealed that the outfall canals needed to be addressed because the existing canal levees did not meet the design heights required by federal design criteria adopted after Hurricane Betsy. However, no immediate guidance was given as to how to increase flood protection along the canals and it remained an unresolved issue for over two decades.[15]

Congress authorized the post-Hurricane-Betsy-modified Barrier Plan when the Flood Control Act of 1965 was passed, positioning the federal government to assume 70 percent of construction costs. After authorization, the New Orleans District set out to develop detailed engineering plans, secure the required funding and real estate, and construct project features. The District initially estimated that the project would be complete by the mid-to-late 1970s.

State governmental elected officials, congressional representatives and various local citizen and interest groups met the Barrier Plan with opposition. Some opponents feared that the barrier would adversely affect navigation access to the lake, while others cited the possible flooding of the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain when the barriers were closed. Also a concern was potential operation and maintenance costs. It was the environmental effects of the barrier, however, that caused the most opposition.

As part of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the New Orleans District prepared an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to address the environmental impacts associated with the project and how the Corps would mitigate those impacts. In 1975, a local environmental advocacy group challenged the adequacy of the 4-page typewritten EIS in U.S. District Court.

Judge Charles Schwartz issued an injunction preventing further progress on the barrier option until the Corps revised its EIS. He also wrote, however, that upon proper compliance with NEPA, ‘the injunction shall be dissolved and any hurricane plan thus properly presented will be allowed to proceed’.[16]

In other words, the Judge invited the Corps to return with a more comprehensive EIS. Ultimately, however, the Corps did not return and, in 1980, concluded that an alternative option of higher levees providing hurricane protection was less costly, less damaging to the environment and more acceptable to local interests.[17]

In 1985, the Director of Civil Works approved increasing levee heights along the lakefront. Construction of other non-barrier features continued as part of the original authorization. With the adoption of the High Level Plan, the New Orleans District could now move forward with providing hurricane and storm surge protection features along the lakefront and outfall canals.

Determining a specific hurricane protection plan for the outfall canals

[edit]Beginning in the late 1970s, the Corps’ New Orleans Board (OLB) began identifying and examining hurricane protection alternatives for the outfall canals. Through a series of Design Memorandums in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Corps recommended building a prototype gate plan employing self-actuating butter-fly check valves at the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue canals. Butterfly gates are hydraulically operated gates that swing on a pivot and close if a storm surge threatens to enter the canals. (It is instructive to note that the gates alternative did not include auxiliary pump stations like those installed after Hurricane Katrina.)

For the 17th Street Canal, the cost of a butterfly gate structure was about the same as the cost of the locally preferred plan of higher parallel levees along each side of the canal, so the corps agreed to pursue “parallel protection” along that canal. There is no stated evidence in the project record that the corps felt that there were differences between the approaches in providing reliable surge protection (Woolley Shabman, 2–48).

However, for the much smaller capacity London and Orleans Avenue Canals, the corps preferred the gates-no-pumps plan because it was significantly less expensive. The parallel protection plan was estimated in the 1980s to cost three times more than the gates plan for the London Avenue Canal and cost five times more than the gates plan for the Orleans Avenue Canal.[18]

The OLB and the Sewerage and Water Board, however, favored parallel protection for the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue outfall canals because they believed interior drainage would be inhibited when the gates were closed during a tropical event because water would not be able to escape from the canals and into Lake Pontchartrain. As interior drainage was not part of the federal authorization for hurricane protection, the OLB and the Sewerage and Water Board would be responsible for any costs associated with pump installation at the mouths of the outfall canals. The OLB and Sewerage and Water Board contended that parallel protection could provide increased hurricane storm surge protection while maintaining interior drainage.

The Corps argued that the butterfly gates plan for the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue canals because they considered it their mandate to build projects with the most favorable cost benefit ratios. Cost was the pre-eminent factor. There is nothing in the project record indicating that the gates-only plan was the superior option, only that it was less expensive.[19]

For several years the project was at a stalemate. The local sponsor successfully lobbied Congress to direct the corps to implement the much more expensive parallel protection plan for all three outfall canals, not just the 17th Street Canal, in the Water Resources Development Act of 1990. Two years later, Congress stipulated that the federal government would pay 70 percent of the cost, with the local sponsor picking up the other 30 percent, in the Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act of 1992.

With the dispute over hurricane protection solutions for the outfall canals seemingly resolved, the Corps began designing and constructing predominantly “I-wall”-type floodwalls on top of the levee crowns. I-walls met the project goals of providing increased embankment heights within the limited existing rights-of-way with minimal disruption to the adjacent residential neighborhoods. Construction began in 1993, and project work along the outfall canals was reported to be nearing completion in 2005 prior to Hurricane Katrina.

Closure structures

[edit]

Despite the dewatering and rapid pace of repairs, the Corps of Engineers determined that it did not have the time to complete repairs to all of the breaches along the outfall canals before the start of the 2006 hurricane season. As a result, the Corps built interim gated closure structures at the mouths of all three canals to prevent storm surge from entering the canals. The Corps also initially installed 34 temporary pumps near the closure structures to drain floodwaters from the sub-basin.[20]

The gated structures stay open during normal, non-tropical conditions. When storm surge threatens to exceed the maximum operating water level of a canal, the Corps closes the gates and operates the pumps. Interior pumps operated by the Sewerage and Water Board pump rainwater out of the sub-basin and into the outfall canals. The interim pumps then pump rainwater out of the outfall canals, around the gates and into Lake Pontchartrain. The closed gates reduce the risk of storm surge entering the canals and threatening the city. When the surge recedes to a safe level, the gates are reopened and normal drainage resumes.

The Corps received authorization to build the interim closure structures under emergency flood control legislation passed in September 2005, specifically Public Law 109-61 and Public Law 109-62. It cost about $400 million to build the interim closure structures.[21][22]

The Corps did not have the authority, however, to build permanent canal closures and pumps under this legislation. It was not until emergency appropriations in the years after Hurricane Katrina that the Corps received authorization to build permanent gates and pumps. This authority superseded any previous legislation prior to Hurricane Katrina that prohibited the Corps from building closure structures at the mouths of the outfall canals. The appropriations for this project total about $804 million.[23]

In the years since Hurricane Katrina, the Corps of Engineers has been constructing and bolstering 350 miles (560 km) of levees, floodwalls, barriers, gates and other structures as part of the Greater New Orleans Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS), which stretches across five parishes and includes much of the original Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity Basin, as well as the West Bank and Vicinity Basin on the West Bank of the Mississippi River. When complete, the HSDRRS will reduce the risk from a storm that has a one percent chance of occurring in any given year, or a 100-year storm.[24]

The interim closure structures already provide a temporary 100-year-level of risk reduction, and the permanent canal closures and pumps will continue to provide that same level of risk reduction. The contract for the permanent canal closures and pumps will be awarded in 2011 and construction will be complete in the fall of 2014.

Outfall canal wall remediation

[edit]Although interim closure structures (and eventually the permanent canal closures and pumps) prevent storm surge from entering the canals and provide the 100-year-level of risk reduction, several portions of the outfall canal floodwalls are being remediated, or strengthened, to meet the more stringent post-Katrina design requirements. When remediation is complete, all canals will be able to operate under a maximum operating water level of +8.0 NAVD 88. All remediation work along the outfall canals will occur within the existing rights-of-way and was scheduled to be completed in June 2011.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ J. David Rogers, G. Paul Kemp (2015). "Interaction between the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Orleans Levee Board preceding the drainage canal wall failures and catastrophic flooding of New Orleans in 2005". Water Policy. p. 712. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers (2009). "Draft Individual Environmental Report: Permanent Protection System for the Outfall Canals Project on 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue Canals" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. p. 69. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Multiple Failures" (PDF). New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District Office, Environmental Planning & Compliance Branch. "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in Louisiana Environmental Assessment EA #433" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Sheet Pile Catalogy"

- ^ Christine F. Anderson, Jurjen A. Battjes; et al. (2007). "The New Orleans Hurricane Protection System: What Went Wrong and Why" (PDF). American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ Sheila Grissett, The Times-Picayune. "Corps analysis shows canal's weaknesses | NOLA.com" (PDF). nola.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ "How Stuff Works". Geography.howstuffworks.com. 2008-03-30. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ Richard Campanella (2010). Bienville's Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. Garrett County Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-891053-19-1.

- ^ "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity Hurricane Protection Project". Government Accountability Office. September 28, 2005. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Outfall Canals and Closure Structures" Archived November 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stephen A. Nelson (2012). "Why New Orleans is Vulnerable to Hurricanes: Geologic and Historical Factors". Tulane University. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ Independent Levee Investigation Team (2006). "Chapter Four: History of the New Orleans Flood Protection System" (PDF). U.C. Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ Interim Survey Report, Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana and Vicinity. New Orleans: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1962. Print

- ^ Douglas Woolley, Leonard Shabman (2008). "Decision-Making Chronology for the Lake Pontchartrain & Vicinity Hurricane Protection Project" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ Douglas A. Kysar, Thomas O. McGarity (2006). "Did NEPA Drown New Orleans? The Levees, the Blame Game, and the Hazards of Hindsight". Duke Law Journal. p. 179. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ Douglas Woolley, Leonard Shabman (2008). "Decision-Making Chronology for the Lake Pontchartrain & Vicinity Hurricane Protection Project" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ J. David Rogers, G. Paul Kemp (2015). "Interaction between the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Orleans Levee Board preceding the drainage canal wall failures and catastrophic flooding of New Orleans in 2005". Water Policy. pp. 712–713. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ Douglas Woolley, Leonard Shabman (2008). "Decision-Making Chronology for the Lake Pontchartrain & Vicinity Hurricane Protection Project" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ "Hurricane Katrina: Strategic Planning Needed to Guide Future Enhancements Beyond Interim Levee Repairs" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. September 1, 2006. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ "Public Law 109-61: An Act Making Emergency Supplemental Appropriations to Meet Immediate Needs Arising from the Consequences of Hurricane Katrina" (PDF). Government Printing Office. September 2, 2005. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ "Public Law 109-62: Second Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act to Meet Immediate Needs Arising from the Consequences of Hurricane Katrina, 2005" (PDF). Government Printing Office. September 8, 2005. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ Woodley, John Paul (February 26, 2009). "Permanent Protection System for Outfall Canals - Report to Congress" (PDF). Department of the Army, Office of the Assistant Secretary. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineering and Construction Bulletin" Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grissett, Sheila (September 14, 2010). "Plan to Fortify 17th Street, London, and Orleans Canals is Meeting Topic Thursday". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2016-01-31.