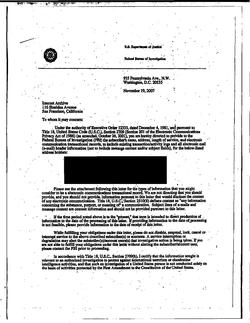

National security letter

A national security letter (NSL) is an administrative subpoena issued by the United States government to gather information for national security purposes. NSLs do not require prior approval from a judge. The Stored Communications Act, Fair Credit Reporting Act, and Right to Financial Privacy Act authorize the United States government to seek such information that is "relevant" to an authorized national security investigation. By law, NSLs can request only non-content information, for example, transactional records and phone numbers dialed, but never the content of telephone calls or e-mails.[1]

NSLs typically contain a nondisclosure requirement forbidding the recipient of an NSL from disclosing the FBI had requested the information.[2] The Director of the FBI must authorize the nondisclosure provisions and only after he or she certifies "that otherwise there may result a danger to the national security of the United States; interference with a criminal, counterterrorism, or counterintelligence investigation; interference with diplomatic relations; or danger to the life or physical safety of any person."[3] Nonetheless, the recipient of an NSL may challenge the nondisclosure provision in federal court.[4]

The constitutionality of such nondisclosure provisions has been repeatedly challenged. The nondisclosure provision was initially ruled unconstitutional as an infringement of free speech in Doe v. Gonzales, but that decision was vacated in 2008 by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals when it held the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act gave the recipient of an NSL that included a nondisclosure provision the right to challenge the nondisclosure provision in federal court. In March 2013, a federal judge in the Northern District of California held an NSL nondisclosure provision was unconstitutional. On August 24, 2015, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the lower court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. On remand, the district court held the "NSLs were issued in full compliance with the procedural and substantive requirements suggested by the Second Circuit in John Doe, Inc. v. Mukasey, 549 F.3d 861 (2d Cir. 2008), which had held that the 2006 NSL law could be constitutionally applied"... and "the NSL law, as amended [by the USA FREEDOM ACT of 2015], was constitutional." The two petitioners appealed. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the district court ruling, holding that NSLs are constitutional and stated, "the nondisclosure requirement does not run afoul of the First Amendment." Under Seal v. Jefferson B. Sessions, III, Attorney General, Nos. 16-16067, 16-16081, and 16-16082, July 17, 2017.

History

[edit]The oldest NSL provisions were created in 1978 as a little-used investigative tool in terrorist and espionage investigations to obtain financial records. Under the Right to Financial Privacy Act (RFPA), part of the Financial Institutions Regulatory and Interest Rate Control Act of 1978, the FBI could obtain the records only if the FBI first demonstrated the target was a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power. Compliance by the recipient of the NSL was voluntary and state laws for consumer privacy often allowed financial institutions to reject the requests.[5] In 1986, Congress amended RFPA to allow the government to request disclosure of the requested information. In 1986, Congress passed the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), part of the Stored Communications Act, which created provisions similar to the RFPA that allowed the FBI to issue NSLs. Still, neither RFPA or ECPA included penalties for failure to comply with the NSL. A 1993 amendment removed the restriction regarding "foreign powers," thereby allowing NSLs to request information concerning persons who are not the direct subject of the investigation but who may have information relevant to it.

In March 2006, the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act specifically allowed for judicial review of NSLs. A federal judge could repeal or modify an NSL if the court found the request for information was "unreasonable, oppressive, or otherwise unlawful." The March 2006 changes also weakened the nondisclosure provision the government could include in an NSL. A court could repeal the nondisclosure provision if it found it had been made in bad faith. Other 2006 amendments to the law allowed the recipient of an NSL to inform their attorney about the NSL and the government had to rely on the courts to enforce compliance with an NSL.[citation needed]

PATRIOT Act

[edit]Section 505 of the USA PATRIOT Act (2001) allowed the use of the NSLs when seeking information "relevant" in authorized national security investigations to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities. The act also provided the Department of Defense when conducting a law enforcement investigation, counterintelligence inquiry, or security determination. The Central Intelligence Agency has also allegedly issued NSLs.[6] The Patriot Act reauthorization statutes passed during the 109th Congress added potential penalties for failure to comply with an NSL or disclosing an NSL if the NSL included a nondisclosure provision.

The PATRIOT Act increased the number of persons who could approve the issuance of NSLs, from the FBI Director (or their designees) to include the FBI Special Agent in Charge of the 56 field offices.[7]

Contentious aspects

[edit]Two contentious aspects of NSLs are the nondisclosure provision and judicial oversight when the FBI issues an NSL, both of which federal courts have held to be constitutional. When the Director of the FBI (or their designee) authorizes the inclusion of a nondisclosure provision in an NSL, the recipient may face criminal prosecution if it discloses the contents of the NSL or that it was received. The purpose of a nondisclosure provision is to prevent the recipient of an NSL from compromising the current FBI investigation involving for which the NSL was issued as well as future investigations (see 18 U.S.C. 2709), either of which would fetter the Government's efforts to address threats to national security.[8] An NSL recipient (later revealed to be Nicholas Merrill[9][10]) writing in The Washington Post said,

[L]iving under the gag order has been stressful and surreal. Under the threat of criminal prosecution, I must hide all aspects of my involvement in the case ... from my colleagues, my family and my friends. When I meet with my attorneys I cannot tell my girlfriend where I am going or where I have been.[8]

Like other administrative subpoenas, NSLs do not require judicial approval. For NSLs, that is because the U.S. Supreme Court has held the type of information NSLs obtain do not have a constitutionally protected reasonable expectation of privacy. The person has already provided the information to a third party, e.g., their telephone company, so they no longer have a reasonable expectation of privacy to the information and, therefore, there is no Fourth Amendment requirement to obtain court approval to obtain the information.[11] Nonetheless, an NSL recipient may still challenge the nondisclosure provision in federal court.[12]

A news media report in 2007 stated a government audit found the FBI had violated the rules more than 1,000 times in an audit of 10% of its national investigations between 2002 and 2007.[13] Twenty such incidents involved requests by agents for information not permitted under the law. A subsequent report in 2014 conduced by the Justice Department's Office of Inspector General concluded the FBI had corrected its practices and that NSLs now complied with federal law.

According to 2,500 pages of documents the FBI provided to the Electronic Frontier Foundation in response to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit in 2007, the FBI had used NSLs to obtain information about individuals who were the subject of an FBI terrorism or counterintelligence investigation and information from telecommunications companies about individuals with whom the subject of the investigation had communicated. According to a September 9, 2007, New York Times report,

In many cases, the target of a[n FBI] national security letter whose records are being sought is not the subject of a terrorism investigation. Under the USA PATRIOT Act, the FBI must assert that the records gathered through the letter are considered relevant to a terrorism [or counterintelligence] investigation.[14]

In April 2008, the American Civil Liberties Union alleged that the military was using the FBI to skirt legal restrictions on domestic surveillance to obtain private records of Americans' Internet service providers, financial institutions, and telephone companies. The ACLU based its allegation on a review of more than 1,000 documents provided by the Defense Department. The Department of Justice Office of Inspector General later determined it was the Department of Defense (not the FBI) that had lawfully obtained the information under the National Security Act of 1947, not by an NSL.

Doe v. Ashcroft

[edit]

The lack of judicial oversight and the Supreme Court ruling in Smith v. Maryland was the core of Doe v. Ashcroft, a test case brought by the ACLU concerning the use of NSLs. The lawsuit was filed on behalf of "John Doe" plaintiff Nicholas Merrill, founder of Calyx Internet Access,[15] who had received an NSL. The action challenged the constitutionality of NSLs, specifically the nondisclosure provision. At the district court, Judge of the Southern District of New York held in September 2004 that NSLs violated the Fourth Amendment ("it has the effect of authorizing coercive searches effectively immune from any judicial process") and First Amendment. However, Judge Marrero stayed his ruling while the case proceeded to the court of appeals.

Because of the New York district court ruling, while the case was still on appeal, Congress amended the USA PATRIOT Act to provide for more judicial review of NSLs and clarified the NSL nondisclosure provision.[16] Based on the U.S. Supreme Court rulings, the FBI does not need judicial approval to issue an NSL.

The government appealed Judge Marrero's decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard arguments in May 2006. In March 2008, the Second Circuit ruled that nondisclosure provisions were permissible only when the FBI certified that disclosure may result in certain statutorily enumerated harms (see, e.g., 18 U.S.C. 2709), and held the nondisclosure provision to a strict scrutiny standard. The Second Circuit then returned the case to the district court based on amendments to the USA PATRIOT Act that Congress had enacted while the case had been on appeal.

Another effect of Doe v. Ashcroft was increased congressional oversight. The amendments to the USA PATRIOT Act mentioned above included requirements for semiannual reporting to Congress. Although the reports are classified, a nonclassified accounting of how many NSLs are issued is also required. On April 28, 2006, the Department of Justice reported to the House and Senate that in calendar year 2005, "The Government made requests for certain information concerning 3,501 United States persons pursuant to NSLs. During this period, the total number of NSL requests ... for information concerning U.S. persons totaled 9,254."[17]

In 2010, the FBI agreed to lift partially the nondisclosure provision to allow Merrill to reveal his identity.[18] On August 28, 2015, Judge Marrero rescinded the nondisclosure provision associated with the NSL Merrill had received, thereby allowing him to speak about the contents of the NSL. On November 30, 2015, the unredacted court ruling was published in full.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005: A Legal Analysis Congressional Research Service's report for Congress, Brian T. Yeh, Charles Doyle, December 21, 2006.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (June 27, 2013). "What It's Like to Get a National-Security Letter". The New Yorker.

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 2709(c)

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 3511

- ^ Andrew E. Nieland, National Security Letters and the Amended Patriot Act, 92 Cornell L. Rev. 1201, 1207 (2007) [1]

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric; Mezzetti, Mark (January 14, 2007). "Military Expands Intelligence Role in U.S." The New York Times.

- ^ Bendix, William; Quirk, Paul J. (2016). "Deliberating Surveillance Policy: Congress, the FBI, and the Abuse of National Security Letters". Journal of Policy History. 28 (3): 447–469. doi:10.1017/S0898030616000178. ISSN 0898-0306. S2CID 156898376.

- ^ a b My National Security Letter, The Washington Post, 2007 Mar 23

- ^ John Doe’ Who Fought FBI Spying Freed From Gag Order After 6 Years Kim Zetter, Wired.com, 2010 8 10

- ^ "Doe v. Holder (Challenging Patriot Act's National Security Letter provision and associated gag provision)". S.D.N.Y. 04 Civ. 2614 (VM) (direct). NYCLU (New York Civil Liberties Union). Archived from the original on 2010-11-13.

- ^ Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979); Fourth Amendment, U.S. Const.

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 3511

- ^ "FBI agents broke the rules 1,000 times". RTÉ News Online. 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric (2007-09-08). "F.B.I. Data Mining Reached Beyond Target Suspects". The New York Times.

- ^ "ACLU Sues Over Internet Privacy". cbsnews.com.

- ^ "Congress.gov – Library of Congress". thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-11-27. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ Report of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Archived 2006-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Justice

- ^ McLaughlin, Jenna (14 September 2015). "Federal Court Lifts National Security Letter Gag Order; First Time in 14 Years". The Intercept. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Nicholas Merrill able to reveal the national security letter previously undisclosed". Information Society Project. Yale University. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

External links

[edit]- National Security Letters in Foreign Intelligence Investigations: A Glimpse of the Legal Background and Recent Amendments (PDF)

- Doe v. Ashcroft decision (PDF)

- Decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in re: John Doe I et al. v. Alberto Gonzales et al. (PDF)

- Documentary film : FBI Unbound: How National Security Letters Violate Our Privacy

- Thousands of Declassified National Security Letters from various government agencies