National Water Carrier of Israel

The National Water Carrier of Israel (Hebrew: המוביל הארצי, HaMovil HaArtzi) is the largest water project in Israel,[1] completed in 1964. Its main purpose is to transfer water from the Sea of Galilee in the north of the country to the highly populated center and the arid south and to enable efficient use of water and regulation of the water supply in the country. It is about 130 kilometers (81 mi) long.[2] Up to 72,000 cubic meters (19,000,000 U.S. gal; 16,000,000 imp gal) of water can flow through the carrier each hour, totalling 1.7 million cubic meters in a day.[3]

The carrier consists of a system of giant pipes, open canals, tunnels, reservoirs and large scale pumping stations. Building the carrier was a considerable technical challenge as it traverses a wide variety of terrain and elevations. Most of the water works in Israel are integrated with the National Water Carrier.

History

[edit]Planning and construction

[edit]While early plans were made before the establishment of the state of Israel, detailed planning began after Israeli independence in 1948. The construction of the project, originally known as the Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan, started in 1953, during the planning phase, long before the detailed final plan was completed in 1956. The project was designed by Tahal and constructed by Mekorot. It was started during the tenure of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, and was completed in June 1964 under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, at a cost of about 420 million Israeli lira (at 1964 values).[1]

Agriculture, drinking water, Jordan's share (1964-1990s)

[edit]The National Water Carrier was inaugurated in 1964, with 80% of its water being allocated to agriculture and 20% for drinking water. As time passed, increasing amounts were consumed as drinking water, and by the early 1990s, the National Carrier was supplying half of the drinking water in Israel. It was forecast that by the year 2010, 80% of the National Carrier would be directed more at providing drinking water. The reasons for the increased demand for drinking water were twofold. First, Israel saw rapid population growth, primarily in the center of the country which increased the demand for water.[1] As the standard of living in the country rose, there was increased domestic water use. As a result of the 1994 Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace, among other items, Israel agreed to transfer 50 million cubic metres of water annually to Jordan.[4]

Since 2015 (after large-scale desalination)

[edit]As of 2016, water from the Sea of Galilee was supplying approximately 10% of Israel's drinking water needs. In the previous years, the Israeli government had undertaken extensive investments in water reclamation and desalination infrastructure in the country, while promoting water conservation. This has lessened the country's reliance on the National Water Carrier and has allowed it to significantly reduce the amount of water pumped from the Sea of Galilee in an effort to restore and improve the lake's ecological environment, especially in face of severe droughts affecting the lake's intake basin in previous years. It was expected that in 2016 only about 25,000,000 cubic metres (880,000,000 cu ft) of water would be drawn from the lake for Israeli domestic water consumption, down from more than 300,000,000 cubic metres (1.1×1010 cu ft) pumped annually a decade earlier.[5]

Route

[edit]

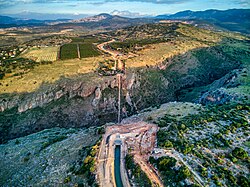

Water first enters the National Water Carrier through a several hundred meter long pipeline which is submerged under the northern part of Sea of Galilee. The water passes into a reservoir on the shore and then travels to a pumping station, initially called "Eshed Kinrot"[6] or "Eshed Kinnarot", later renamed "Sapir" (English name: Sapir Pumping Station) after Pinhas Sapir, co-founder of Mekorot in 1937 (see also Tel Kinrot for the site).[7]

The pipeline entering the lake is composed of nine pipes which are joined by an internal cable threaded through them. Each of these pipes includes twelve concrete pipes, each five meters long and three meters wide. As these pipes were cast, they were encased in steel pipes, sealed at the ends and floated out onto the lake. A winged star-shaped cap is mounted in a vertical section of the underwater pipe to allow water to be taken in from all directions.[1]

Water travels to the Sapir Pumping Station on the shore of the lake where four horizontal pumps lift the water into three pipes which subsequently join to form the pressure pipe, a 2,200-meter (7,200 ft) long pressure-resistant steel pipe, which raises the water from -213 meters below sea level to +44 meters. From here, the water flows into the Jordan Canal, an open canal. This runs along a mountainside for most of its 17 km (11 mi) route. When full, the water in the canal is 2.7 meters (8.9 ft) deep and flows purely by gravity apart from where two deep wadis intersect the course of the canal, Nahal Amud and Nahal Tzalmon. To overcome these obstacles, water is carried through inverted siphons.[1]

The canal transfers the water into the Tzalmon Reservoir, a 1 hm3 operational reservoir in the Nahal Tzalmon valley. Here, the second pumping station in the course of the Water Carrier is located, the Tzalmon Pumping Station which is designed to lift water an additional 115 meters (377 ft). Water then enters the Ya’akov Tunnel which is 850 m (2,790 ft) long and 3 meters in diameter. This flows under hills near the village of Eilabun and transfers the water from the Jordan Canal to the open canal crossing which crosses the Beit Netofa Valley – the Beit Netofa Canal.[1] The Beit Netofa Canal takes the water 17 kilometers and was built with an oval base due to the clay soil through which it runs. The width of the canal is 19.4 meters, the bottom is 12 meters wide and it is 2.60 meters deep, with the water flowing through it at a height of 2.15 meters.

The advanced Eshkol Water Filtration Plant, completed in 2007-2008 by Mekorot,[8] the fourth largest in the world,[9] is located at the southwestern edge of the Beit Netofa Valley. The water first passes through two large reservoirs. The first of these is a sedimentation pond, holding about 1.5 million m³ of water, which allow suspended matter in the water to settle to the bottom, thus cleaning the water. The second reservoir is separated from the sedimentation pond by a dam and has a capacity of 4.5 million m³. Here the inflow of water from the pumping stations and open canals is regulated against the outflow into the closed pipeline. The amount allowed through depends on water demand. A special canal bypasses the reservoirs allowing water to travel straight through the carrier.[1] Before entering the closed pipeline, final tests are performed on the water in the carrier, with chemicals added to bring the water to drinking standards. At the end of the filtration process the water enters the 108" Pipeline, which transports it 86 km to the Yarkon-Negev system near the city of Rosh HaAyin to the east of Tel Aviv and Petah Tikva.[1]

Alternative plans

[edit]Herzl plan

[edit]The initial idea of a National Water Carrier followed the proposal of several solutions for the water problems of Palestine put forward before the establishment of Israel in 1948. Early ideas appeared in the 1902 book Altneuland by Theodor Herzl in which he talked about utilizing the sources of the Jordan River for irrigation purposes and channeling sea water for producing electricity from the Mediterranean Sea near Haifa through the Beit She'an and Jordan valleys to a canal which ran parallel to the Jordan River and the Dead Sea.[1]

Hayes plan

[edit]An earlier water development scheme was proposed by Walter C. Lowdermilk in his book Palestine, Land of Promise, published in 1944. It was developed with human and financial assistance from the American Zionist Emergency Council. The book became a bestseller, and important in swaying the debate within the Truman administration concerning immigrant absorptive capacity and the Negev as part of Israel.[10] His book served as the basis for a detailed water resource plan which was prepared by James Hayes, an engineer from the USA, who proposed utilizing all water sources in Israel (2 km3 per annum) for irrigation and the production of electricity.[1] This would involve diverting part of the Litani River water to the Hasbani River.[1] This water which would be further transported by a dam and canal to the area south of Tel Hai, from where it would be "dropped" to produce electricity.[1] Water would also be carried from Tel Hai to the Beit Netofa Valley which would become a national water reservoir, of about one billion cu.m. volume (one quarter of the Sea of Galilee's volume).[1] An electricity generating station would be located at the reservoir's outlet, from where the water would flow into an open canal to Rafiah, which, whilst travelling south would collect water from wadis and streams, including the waters of the Yarkon River.[1] Hayes also asserted that the Yarmouk River would be channeled into Lake Kinneret, in order to prevent a rise in its salinity which could come about as a result of the diversion of the River Jordan, and that a joint Israeli-Jordanian dam about 5 km east of kibbutz Sha'ar HaGolan would be constructed. The Hayes plan was designed to be implemented in two stages over a 10-year period, but never materialised due to its economic infeasibility and lack of cooperation by Jordan.[1]

Johnston Plan

[edit]Eric Johnston, the water envoy of US President Dwight Eisenhower between 1954 and 1957, developed another water plan for Israel, which became known as the Johnston Plan. In this, water from the Jordan River and Yarmuk River would be divided between Israel (40%), Jordan (45%) and Syria and Lebanon (15%). Each country would keep its right to utilize the water flowing within its borders, if it caused no harm to a neighboring country. Whilst this plan was accepted as fair by Arab water experts, it later floundered as a result of increasing tensions in the region, but was later seriously considered by Arab leaders.[qt 1]

Tensions with Syria and Jordan

[edit]Since its construction, the resulting diversion of water from the Jordan River has been a source of tension with Syria and Jordan.[11][12] In 1964, Syria attempted construction of a Headwater Diversion Plan that would have prevented Israel from using a major portion of its water allocation,[qt 2] sharply reducing the capacity of the carrier.[13] This project and Israel's subsequent physical attack on those diversion efforts in 1965 were factors which played into regional tensions culminating in the 1967 Six-Day War.[14] In the course of the war, Israel captured from Syria the Golan Heights, which contain some of the sources of the Sea of Galilee.

Receding Dead Sea and sinkholes

[edit]The surface of the Dead Sea has shrunk by about 33% since the 1960s, which is partly attributed to the much-reduced flow of the Jordan River since the construction of the National Water Carrier project. The EcoPeace Middle East, a joint Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian environmental group, has estimated that the annual flow into the Dead Sea from the Jordan is as of 2021[update] less than 100,000,000 cubic metres (3.5×109 cu ft) of water, compared with former flows of between 1,200,000,000 cubic metres (4.2×1010 cu ft) and 1,300,000,000 cubic metres (4.6×1010 cu ft).[15]

The water level of the Dead Sea had been declining, as of 2021[update], at an annual rate of more than a metre, which is attributed to the battle for scarce water resources in the very arid region.[15]

One effect of the shrinking of the Dead Sea is the apparition of sinkholes along its shores. The sinkholes form as a result of the receding shoreline, where a thick layer of underground salt is left behind. When fresh water arrives in the form of heavy rains, it dissolves the salt as it sinks into the ground, forming an underground cavity, which eventually collapses under the weight of the surface ground layer. At Ein Gedi for instance, on the western coast of the Dead Sea, a large number of sinkholes have appeared in the area, which have even damaged a highway segment built in 2010, supposedly to a "sinkhole-proof" design.[15]

The Dead Sea is further shrinking due to the diminished amount of water from the rains reaching it since flash floods started pouring into the sinkholes.[15]

See also

[edit]- Water supply and sanitation in Israel

- Water politics

- Water politics in the Middle East

- Water politics in the Jordan River basin

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kantor, Shmuel. "The National Water Carrier". the University of Haifa. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ^ "National Water Carrier". JAFI. Archived from the original on 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ Waldoks, Ehud Zion (2008-02-18). "Inside the National Water Carrier". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2008-04-05.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Developments related to the Middle East Peace Process". UN. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ^ Amit, Hagai (1 June 2016). "הקו האדום של הכנרת נהפך לבעיה של הירדנים" [The Kinneret's Red Line has Turned into Jordan's Problem]. TheMarker. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Reguer, Sara (Jan 1993). "Controversial Waters: Exploitation of the Jordan River, 1950-80". Middle Eastern Studies. 29 (1). Taylor & Francis: 53–90. doi:10.1080/00263209308700934. JSTOR 4283541. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Naor, Mordechai. The Founding of Mekorot. Mekorot homepage. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Eshkol Water Filtration Plant". Water Technology. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Central Water Filtration Factory (Hebrew)

- ^ Rafael Medoff, Jewish Americans and political participation: a reference handbook

- ^ Bleier, Ronald. "Israel's Appropriation of Arab Water: An Obstacle to Peace". Retrieved 2013-11-18.

- ^ Lendman, Stephen (2008-07-18). "Drought and Israeli Policy Threaten West Bank Water Security". Global Policy Forum. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ^ Fischhendler, Itay (2008). "When Ambiguity in Treaty Design Becomes Destructive: A Study of Transboundary Water". Global Environmental Politics. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ^ Seliktar, Ofira (June 2005). "Turning Water into Fire: the Jordan River as the Hidden Factor in The Six Day War". The Middle East Review of International Affairs. 9 (2).

- ^ a b c d Tlozek, Eric (10 June 2021). "The Dead Sea is disappearing, leaving behind a landscape shattered by sinkholes". ABC News. Cinematography: Alon Farago and Abu Saada; Graphics: Andres Gomez Isaza. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

Quotes

[edit]- ^ Gat, Moshe (2003). Britain and the Conflict in the Middle East, 1964-1967: The Coming of the Six-Day War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-275-97514-2. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

[in 1965] Nasser, too, assured the American undersecretary of state, Philip Talbot, that the Arabs would not exceed the water quotas prescribed by the Johnston plan.

- ^ Murakami, Masahiro (1995). Managing Water for Peace in the Middle East; Alternative Strategies. United Nations University Press. pp. 287–297 [295–297]. ISBN 978-92-808-0858-2. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

The initial diversion capacity of the National Water Carrier without supplementary booster pumps was 320 million m3, well within the limits of the Johnston Plan. ......Shortly before completion of the Israeli Water Carrier in 1964, an Arab summit conference decided to try to thwart it. Discarding direct military attack, the Arab states chose to divert the Jordan headwater......the Arab states chose to divert the Jordan headwaters.......diversion of both the Hasbani and the Banias to the Yarmouk.....According to neutral assessments, the scheme was only marginally feasible; it was technically difficult and expensive......Political considerations cited by the Arabs in rejecting the 1955 Johnston Plan were revived to justify the diversion scheme. Particular emphasis was placed on the Carrier's capability to enhance Israel's capacity to absorb immigrants to the detriment of Palestinian refugees. In response, Israel stressed that the National Water Carrier was within the limits of the Johnston Plan......the Arabs started work on the Headwater Diversion project in 1965. Israel declared that it would regard such diversion as an infringement of its sovereign rights. According to estimates, completion of the project would have deprived Israel of 35% of its contemplated withdrawal from the upper Jordan, constituting one-ninth of Israel's annual water budget.......In a series of military strikes, Israel hit the diversion works. The attacks culminated in April 1967 in air strikes deep inside Syria. The increase in water-related Arab-Israeli hostility was a major factor leading to the June 1967 war.

The text of the book is also posted here on the UN University website.

External links

[edit]- Description of the National Water Carrier by Shmuel Kantor, former chief engineer of Mekorot, Israel's national water company

- Fossil Water Reserves - Israel - from two hundred billion (109) to "several hundred billion" cubic meters of water