Narcissa Whitman

Narcissa Whitman | |

|---|---|

Narcissa Whitman | |

| Born | March 14, 1808 Prattsburgh, New York, U.S. |

| Died | November 29, 1847 (aged 39) Waiilatpu, Washington, U.S. |

| Occupation | Missionary |

| Spouse | Marcus Whitman |

Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (March 14, 1808 – November 29, 1847) was an American missionary in the Oregon Country of what would become the state of Washington. On their way to found the Protestant Whitman Mission in 1836 with her husband, Marcus, near modern-day Walla Walla, Washington, she and Eliza Hart Spalding (wife of Henry Spalding) became the first documented European-American women to cross the Rocky Mountains.[1]

Early life

[edit]Narcissa Prentiss was born in Prattsburgh, New York, on March 14, 1808. She was the third of nine children of Judge Stephen and Clarissa Prentiss, was the oldest of the five girls, followed by Clarissa, Mary Ann, Jane, and Harriet, and had four brothers. In 1819, Narcissa had a religious awakening and converted to the Congregational Church. She was educated at the Franklin Academy in Prattsburgh, and for a time, taught primary school in there. Like many young women of the era, she became caught up in the Second Great Awakening. She decided that her true calling was to become a missionary, and was accepted for missionary service in March 1835.[2] However, she was rejected for foreign mission because she was unmarried, a problem she solved by suddenly marrying Dr. Marcus Whitman on February 18, 1836, in Angelica, New York.[3] Her birthplace in Prattsburgh is open to the public as the Narcissa Prentiss House.[4][5] While the name is not much used today, the road from Prattsburgh, New York to Naples, New York was formerly called the Narcissa Prentiss Highway.[6]

Journey west

[edit]Shortly after their wedding, the Whitmans along with the also recently married Henry and Eliza Spalding headed west for the Oregon Country in March 1836 to begin their missionary activities amongst the natives.[3] The journey was by sleigh, canal barge, wagon, river sternwheeler, horseback, and foot. Narcissa kept a journal of the trip. The founder of Ogden, Utah, Miles Goodyear, traveled with them until Fort Hall. On September 1, 1836, they arrived at Fort Walla Walla, a Hudson's Bay Company outpost near present-day Walla Walla, Washington. They then traveled on to Fort Vancouver where they were hosted by Dr. John McLoughlin before returning to the Walla Walla area to build their mission. Whitman and Spalding were the first white women to cross the Rocky Mountains and live in the area. She was something of a novel addition to the community for the local Native Americans, the Cayuse.[7]

Whitman Mission

[edit]The Whitman Mission began to take shape in 1837, eventually growing into a major stopping point along the Oregon Trail.[3] Methodist missionary Jason Lee would stop off in 1838 at the mission on his way east to gather reinforcements in the United States for his mission in the Willamette Valley. Then, in 1840, mountain man Joseph Meek, whom the Whitmans met on their journey to the area, stopped off on his way to the Willamette Valley.

Built at Waiilatpu, the settlement was about six miles (10 km) from Fort Walla Walla and along the Walla Walla River.[3] At the mission, Whitman gave Bible classes to the native population, as well as teaching them Western domestic chores that were unknown to the Native Americans. Besides the missionary goals of converting the natives, she also ran the household. Her daily activities included cooking, washing and ironing clothes, churning butter, making candles and soap, and baking. Her letters home recounted her loneliness and life at the mission.[1]

On March 14, 1837, on her twenty ninth birthday, Whitman gave birth to the first white American born in Oregon Country.[3] She named her Alice Clarissa after her grandmothers, and she would be their only natural child. Unfortunately, the child drowned in the Walla Walla River on June 23, 1839, at age two. Unattended for only a few moments, she had gone down to the river bank to fill her cup with water and fell in. Though her body was found shortly after, all attempts to revive her failed. However, other children came to the mission, including the Sager orphans, to whom Whitman became a second mother.[2]

Just before winter, in late 1842, Marcus traveled back east to recruit more missionaries for the mission.[3] During the time he was away, Whitman traveled west and visited other outposts in the territory including Fort Vancouver, Jason Lee's Methodist Mission near present-day Salem, Oregon, and another mission near Astoria, Oregon. Marcus returned with his nephew, Perrin, from his trip east in 1843.

Whitman massacre

[edit]Throughout their time in Oregon Country, the Whitmans periodically encountered trouble with the native tribes.[3] The Cayuse and the Nez Percé tribes were suspicious of the activities and the encroachment of the Americans. As early as 1841, Tiloukaikt had tried to force them to leave Waiilatpu and the ancestral homeland.

In 1847, a measles epidemic broke out among the native population,[3] which lacked immunity to the disease and it spread quickly. The American population had some limited immunity to measles which meant a lower mortality rate than the natives. This discrepancy stirred discontent among the natives who felt Marcus was only curing the white people while letting Indian children die. The resentment boiled over on November 29, 1847, when Tiloukaikt and others attacked the mission, killing both Whitmans. This event would be remembered as the Whitman massacre, in which eleven others were killed, including the young brothers John and Francis Sager. Many more were taken hostage.[8] Five Cayuse were hanged for murder; see Cayuse Five.

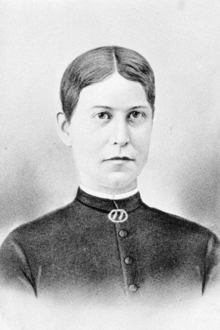

Likeness

[edit]

According to author O. W. Nixon, who published a portrait of Whitman drawn after her death: "No authentic picture of Mrs. Whitman is in existence. This portrait of her has been drawn under the supervision of a gentleman familiar with her appearance and with suggestions from members of her family. It is considered a good likeness of her."[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Edwards, G. Thomas. "Narcissa Whitman (1808–1847)". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Whitman Mission National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". Biography of Narcissa Whitman. 2015-04-13. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Allen, Opal Sweazea. Narcissa Whitman: An Historical Biography. Binfords & Mort, 1959.

- ^ Applebee, Lenora J., Around Prattsburgh, Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing (2012), pp. 12, 13, 16.

- ^ Buck, Rinker (2015). The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-5917-7.

- ^ House, Kirk, "Steuben County People on the Maps of Two Worlds," Steuben Echoes 44:4, November 2018, p. 9.

- ^ Nash, Gary, The American People, 6th concise ed., New York: Pearson Longman, p. 387.

- ^ "Narcissa Biography". Whitman Mission National Historic Site. 2004-01-31. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05.

- ^ Drury, Clifford Merrill (1937). Marcus Whitman, M. D.: Pioneer and Martyr. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. p. 128.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. Converting the West: A Biography of Narcissa Whitman. University of Oklahoma Press, 1991

- Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo. The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. University of Nebraska Press, 1989, 1996

- Thompson, Erwin N. Whitman Mission National Historic Site: Here They Labored Among the Cayuse Indians. National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 37, 1964

- Eaton, Jeanette. Narcissa Whitman: Pioneer of Oregon. Harcourt, Brace, & Co., 1941

External links

[edit]- "How One Woman Saved Three States for Union". Madera Mercury. November 1, 1925. Retrieved August 30, 2018 – via California Digital Newspaper Archive (University of California, Riverside).

- 1808 births

- 1847 deaths

- 1847 murders in the United States

- 19th-century American people

- 19th-century American women

- People from Prattsburgh, New York

- American Presbyterian missionaries

- Presbyterian missionaries in the United States

- Cayuse War

- Female Christian missionaries

- Female murder victims

- Oregon Country

- Oregon pioneers

- Oregon Trail

- Washington (state) pioneers

- Pre-statehood history of Washington (state)

- People murdered in Washington (state)

- Cowgirl Hall of Fame inductees