Natural History Museum, Berlin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

| |

| |

| Established | 1810 |

|---|---|

| Location | Invalidenstraße 43 10115 Berlin, Germany |

| Coordinates | 52°31′48″N 13°22′46″E / 52.53000°N 13.37944°E |

| Type | Natural history museum |

| Director | Johannes Vogel |

| Website | www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin |

The Natural History Museum (German: Museum für Naturkunde) is a natural history museum located in Berlin, Germany. It exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history and in such domain it is one of three major museums in Germany alongside Naturmuseum Senckenberg in Frankfurt and Museum Koenig in Bonn.

The museum houses more than 30 million zoological, paleontological, and mineralogical specimens, including more than ten thousand type specimens. It is famous for two exhibits: the largest mounted dinosaur in the world (a Giraffatitan skeleton), and a well-preserved specimen of the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx. The museum's mineral collections date back to the Prussian Academy of Sciences of 1700. Important historic zoological specimens include those recovered by the German deep-sea Valdiva expedition (1898–99), the German Southpolar Expedition (1901–03), and the German Sunda Expedition (1929–31). Expeditions to fossil beds in Tendaguru in former Deutsch Ostafrika (today Tanzania) unearthed rich paleontological treasures. The collections are so extensive that less than 1 in 5000 specimens is exhibited, and they attract researchers from around the world. Additional exhibits include a mineral collection representing 75% of the minerals in the world, a large meteor collection, the largest piece of amber in the world; exhibits of the now-extinct quagga, huia, and tasmanian tiger, and "Bobby" the gorilla, a Berlin Zoo celebrity from the 1920s and 1930s.

In November 2018 the German government and the city of Berlin decided to expand and improve the building for more than €600 million.[1]

Name

[edit]The museum's name has changed several times. German speakers mainly call this museum Museum für Naturkunde since this is the term on the façade. It is also called Naturkundemuseum or even Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin so that it can be distinguished from other museums in Germany also named as Museum für Naturkunde. The museum was founded in 1810 as a part of the Berlin University, which changed its name to Humboldt University of Berlin in 1949. For much of its history, the museum was known as the "Humboldt Museum",[2] but in 2009 it left the university to join the Leibniz Association. The current official name is Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung and the "Humboldt" name is no longer related to this museum. Furthermore: there is another Humboldt-Museum in Berlin in Tegel Palace dealing with brothers Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt.

The Berlin U-Bahn station Naturkundemuseum is named after the museum.

Exhibitions

[edit]

Since the museum renovation in 2007, a large hall explains biodiversity and the processes of evolution, while several rooms feature regularly changing special exhibitions.

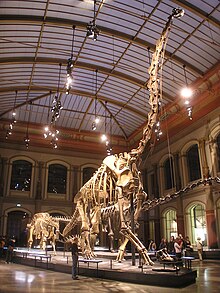

Dinosaur Hall

[edit]The specimen of Giraffatitan brancai[3] in the central exhibit hall is the largest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world.

It is composed of fossilized bones recovered by the German paleontologist Werner Janensch from the fossil-rich Tendaguru beds of Tanzania between 1909 and 1913. The remains are primarily from one gigantic animal, except for a few tail bones (caudal vertebrae), which belong to another animal of the same size and species.

The historical mount (until about 2005) was 12.72 m (41 ft 5 in) tall, and 22.25 m (73 ft) long. In 2007 it was remounted according to new scientific evidence, reaching a height of 13.27 m. When living, the long-tailed, long-necked herbivore probably weighed 50 t (55 tons). While the Diplodocus carnegiei mounted next to it (a copy of an original from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, United States) actually exceeds it in length (27 m, or 90 ft), the Berlin specimen is taller, and far more massive.

Archaeopteryx

[edit]The "Berlin Specimen" of Archaeopteryx lithographica (HMN 1880), is displayed in the central exhibit hall. The dinosaur-like body with an attached tooth-filled head, wings, claws, long lizard-like tail, and the clear impression of feathers in the surrounding stone is strong evidence of the link between reptiles and birds. The Archaeopteryx is a transitional fossil; and the time of its discovery was apt: coming on the heels of Darwin's 1859 magnum opus, The Origin of Species, made it quite possibly the most famous fossil in the world.

Recovered from the German Solnhofen limestone beds in 1871, it is one of 12 Archaeopteryx to be discovered and the most complete. The first specimen, a single 150-million-year-old feather found in 1860, is also in the possession of the museum.

Minerals Halls

[edit]The MFN's collection comprises roughly 250,000 specimens of minerals, of which roughly 4,500 are on exhibit in the Hall of Minerals.[4][5]

Evolution in action

[edit]A large hall explains the principles of evolution. It was opened in 2007 after a major renovation of parts of the building.

Tristan – Berlin bares teeth

[edit]

The Museum für Naturkunde normally exhibits one of the best-preserved Tyrannosaurus skeletons ("Tristan") worldwide. Of approximately 300 bones, 170 have been preserved, which puts it in the third position among others.[6]

Wet Collection

[edit]The glass-walled Wet Collection Wing with 12.6 km of shelf space displays one million specimens preserved in an ethanol solution and held in 276,000 jars.[7]

History

[edit]

The collection history

[edit]19th century to 1945

When the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin, now the Humboldt University of Berlin, opened in 1810, the existing scientific and medical collections were combined and made accessible to the public for the first time. Therefore the Geological-Paleontological Museum, the Mineralogical-Petrographic Museum and the Zoological Museum were founded and were open to anyone interested to visit. Around 1880, the constantly growing collections based on donations, purchases and expedition finds took up around two thirds of the space in the main building, Unter den Linden, and “formed an oppressive burden”. The royal state government therefore decided in 1874 to build new buildings for the agricultural college and the collection of the Museum of Natural History on the site of the already closed Royal Iron Foundry on Invalidenstrasse. The architectural competition that was announced contained the requirements to enable all collection elements to be arranged as uniformly as possible.[8] The winner of the competition was the architect August Tiede, who initially suggested storing the exhibits separately, but then had to give up.

As a result, a multi-wing building was built at Invalidenstrasse 43 between 1875 and 1880 under the senior construction management of Friedrich Kleinwächter and the construction management of the government architect Hein. The opening was celebrated on December 2, 1889.[9][10]

Contrary to initial plans, the Natural History Museum only made part of its holdings accessible to the public as a display collection, while the main collection was reserved for interdisciplinary research work. This practice, which is common today, was considered revolutionary at the time.[11] The first building extension was built between 1914 and 1917.

In the 1910s and 1920s, the facility on Invalidenstrasse was called the Museum of Natural History and Zoological Institute. It was divided into the Geological-Paleontological Institute and Museum, the Mineralogical-Petrographic Institute and Museum, the Zoological Institute and Museum and had several employees such as university lecturers, taxidermists, castellans, stokers, machine masters, servants, caretakers, library servants.[12]

During World War II, the east wing of the museum building was heavily damaged in a daytime raid by the United States Army Air Forces on February 3, 1945. While large parts of the building collapsed, several people died in the air raid shelter. Large whale skeletons from the collection were buried and the exhibition rooms for insects and mammals were destroyed.[13] About 75 percent of the collection was brought to safety.[11]

After the war until 2015

On September 16, 1945, the Natural History Museum, which was now located in the Soviet sector of Berlin, was the first Berlin museum to reopen after the end of the war. The years after the war were characterized by repairing the war damage to the building and securing the collections. From the 1950s onwards, the museum showed new permanent exhibitions. During the GDR era, the collections were expanded with finds from research trips to Cuba, Mongolia and the Soviet Union, for example fossilized plants from the Mongolian steppe or a coral reef from Cuba. Visits by representatives of Western countries, however, remained the exception.[11]

In reunified Germany, the museum was initially reorganized into three institutes: mineralogy, paleontology and systematic zoology. The building was renovated and subjected to extensive modernization. In 2006, a further reorganization followed into three departments for research, collections, exhibitions and public education.[11]

In 2005, the dinosaur skeletons on display were temporarily dismantled to make room for the upcoming renovation of the roof and the entire large exhibition hall, which was financed with funds from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the State of Berlin and the German Class Lotterie Berlin Foundation. In total, four halls and a staircase were renovated and completely redesigned with multimedia components at a cost of around 16 million euros. The reopening took place on July 13, 2007 with new exhibitions on the evolution of life and the earth. Within a year of this reopening, over 731,000 visitors visited the museum.

Due to its supra-regional importance, the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin was granted the status of a foundation under public law on January 1, 2009 and was accepted as a member of the Leibniz Association.[11]

Since the 2020s

An international architectural competition started on December 23, 2022 to fundamentally repair the historic building stock and to supplement and expand the available space with new buildings. The mission is Museum of Natural History – Future Plan for the Science Campus, i.e. h. A new science campus is to be built. The basis for this competition is the agenda “Future plan – conceptual and structural development perspectives for the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin” developed by the museum management in 2018. The museum should live up to its responsibility as a “place of information, reflection and discussion with society”. The three main functional areas – collections and collection infrastructure, research infrastructure and science communication/visitor infrastructure – are to be strengthened.[14]

The building history

[edit]Overview

As a result of the continuously growing natural science collections, a complex new exhibition building was planned on the site of the former Royal Iron Foundry on Invalidenstrasse, in which the three museums mentioned above would be combined. The new building ensemble was given the name Museum für Naturkunde during the planning phase, consisting of the corresponding central collection and the parts of the Prussian Geological State Institute with the Mining Academy (Geological State Institute and Mining Academy) and the Berlin Agricultural University.

The university management, together with the Berlin magistrate, announced an architectural competition, which August Tiede won with his multi-wing project proposal.

All construction costs including the interior furnishings amounted to around 3.2 million marks.[8]

Building descriptions with additions and conversions

August Tiede planned the buildings uniformly in historicizing classical forms (“in the Hellenistic sense”), based on the Louvre in Paris. The three parts of the building along Invalidenstrasse as the front side are generously grouped around a courtyard-like forecourt. The connecting elements were front gardens, which were laid out between 1883 and 1889 according to plans by the garden architect Richard Köhler, and a fountain in front of the central building. In addition, an area of around 500 m² was left free from the former foundry site, which was intended to widen Invalidenstrasse.[8] And according to the construction plans, once the complex was completed, all three parts were to be connected to each other by side halls.[8]

All elements of the building ensemble were heated by a central boiler house, which stood in the third northern courtyard of the natural history building. Individual solutions had to be created for the furnishings (cupboards, drawers, consoles, cross beams, glass panels) and equipment as well as the entire color scheme.

Museum of Natural History

The building area with a size of 20,071 m² is located on the ploten Invalidstrasse 43. As early as 1915/1916, the three northern wings of the main building received an extension to accommodate the zoological collection.

It is an almost square main building with a front length of 85 m, to which an approximately 140 m long four-wing cross wing was added at the back, designed as a simple brick building. The wing buildings facing north are around 37 m long and there are three 23 m wide courtyards in between. The facades of the main building are clad with tuff stone and Rackwitz sandstone. Other wall materials used were bricks, Old Warthauer sandstone, Main sandstone, polished Swedish granite, Belgian limestone and artificial marble.[8]

A three-axis, slightly sculpturally structured raised central projection characterizes the street facade of the building. The top floor is decorated with Corinthian double columns, two statues and three relief portraits of famous scientists: Johannes Müller and Leopold von Buch, as well as Chr. G. Ehrenberg, Alexander von Humboldt and Chr. Sam. White above the second floor windows in laurel-crowned medallions created by sculptor August Ohrmann. A wide staircase leads into the interior with a foyer, followed by an atrium reserved for the large exhibits of the animal collection.

The collection and work rooms inside are wide-span halls on iron supports; the vaults between the iron girders are made of porous stones. On the two gable ends of the main building there are large staircases in iron constructions and work rooms for supervisory officers of the individual departments of the museum. The rear wing structures are finished with cast plaster caps between the iron beams and a supporting corrugated iron covering.

For the floors, Tiede used terrazzo and oak rods in asphalt. Within the museum building there were two lecture halls and apartments for the curator. The ground floor and first floor of the western wing formed a complete service building for the museum director and his family.[8]

In the basement of the eastern wing, a drying chamber and degreasing and maceration systems were installed, which were supplied by the Berlin company E. A. Lentz. Even safety measures against water/moisture and fire have been taken into account.[8]

State Geological Institute and Mining Academy

The construction area at Invalidenstrasse 44 covered 12,028 m².[8] These additional buildings were also opened in 1889. The state geological institute needed additional space after just under 15 years. A north wing was built between 1890 and 1892 based on plans by Fritz Laske and a further extension was built in 1913.

The mining academy used the ground floor rooms around a large atrium, the state geological institute was located on the floors above. Circumferential column arcades structured the atrium. Worth mentioning here were a bench with the motif of the Prussian eagle, two lying stone lions on the stair stringers, a cast-iron group of lions at the courtyard entrance, and a sitting dog cast from bronze on the outside of the side portal. This is a replica of the Molossian dogs from the second half of the 3rd century BC. BC, who were posted as a couple in front of the former veterinary college; however, the second figure was lost. Except for the dogs, these were historical pieces of equipment from the former iron foundry at this location, manufactured in 1867.

Agricultural college

The construction area for the Agricultural University with 11,204 m²[8] is located on the Invalidenstrasse 42 plot. This building was also completed in 1889, and expansion work had to be carried out after a very short time (1876–1880). This also resulted in a multi-wing facility that was planned and realized by Kern & Krencker and E. Gerhardt.

A glass-covered atrium forms the center, in which there is a statue of Albrecht Daniel Thaer, a German researcher, designed by Christian Daniel Rauch. Attached to the atrium is a staircase with a spacious vestibule. The floors on the upper ground floor are decorated with ornamental mosaics. In the northwest part of the university building, a cast iron staircase leads to the upper floors. In four wall niches around the atrium, famous agricultural researchers are honored with marble busts.

Post-war work and modernizations

At the end of the Second World War, the museum ensemble was severely damaged by a bombing raid (as shown under History) and in later street fighting.

The ruins of the Natural History Museum were then briefly rebuilt and could continue to be used, but the east wing remained empty for the time being.

The western part of the building ensemble was repaired in a simplified form after the war in 1946/1947 under the direction of Walter Krüger. Although procurement was not easy, color-coordinated natural stones were used.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the administrative reform, Max Dudler was able to restore the wing of the Geological State Institute from 1996 to 2000 with financial support from the Berlin Senate. Since the German government moved to Berlin, it has housed the Federal Ministry for Digital Affairs and Transport.

From mid-November 2006, after ten years of planning, the reconstruction of the east wing of the Natural History Museum, estimated at 29.6 million euros, began as a modern concrete building with historical facade reliefs. After four years of construction, the part of the building was opened to the public in September 2010 in time for the Natural History Museum's 200th birthday. In January 2012, the reconstruction carried out by the architectural firm Diener & Diener received the DAM Prize for Architecture in Germany.

Just twelve years later, in November 2018, the state of Berlin and the federal government decided to expand and renovate the house for over 600 million euros.[15][16] Among other things, the exhibition area was increased from 5,000 to 25,000 square meters and the digital development of the collection was promoted.[17] The latter can be observed live in one of the exhibition halls (due to the corona pandemic, the exhibitions were closed from March 2020 to the end of 2022).

See also

[edit]- List of museums in Germany

- List of natural history museums

- List of tourist attractions in Berlin

- Biodiversity Heritage Library for Europe (Museum für Naturkunde is a lead institution)

- Zoosystematics and Evolution, Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift and Fossil Record (scholarly journals associated with the museum)

References

[edit]- ^ Sentker, Andreas. "Ideen für das Überleben der Menschheit". 2018-11-14 (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ See page 19: "MB: Berlin Museum für Naturkunde (formerly Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde)" in Kenneth Carpenter, Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs, Indiana University Press, 384 pages, 2006, ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3

- ^ Gregory S. Paul formally moved the Brachiosaurus brancai species to a new subgenus (Giraffatitan) in 1988, and George Olshevsky promoted the new taxa to genus in 1991. Although the change has been generally accepted among scientists, as of 2015 the museum's labels still use the old genus name.

- ^ Süddeutsche Zeitung Online Wissenschaft im Paradies – Schöner forschen, accessed 9 September 2011

- ^ MFN entry in the database University museums and collections in Germany of the Hermann von Helmholtz-Zentrums für Kulturtechnik, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 9 September 2011

- ^ Tristan exhibition Tristan – Berlin bares teeth, Retrieved 4 February 2017

- ^ Wet Collection Wet Collections, accessed 28 September 2019

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kleinwächter, Friedrich (1891). "Das Museum für Naturkunde". Zeitschrift für Bauwesen. p. 1.

- ^ "Das Museum für Naturkunde der Königlichen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin zur Eröffnungs-Feier". Berlin: Ernst & Korn.[dead link]

- ^ Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin.; Berlin, Museum für Naturkunde in (1889). Das Museum für Naturkunde der Königlichen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin : Zur eröffnungs-feier. Berlin: Ernst & Korn.

- ^ a b c d e "Geschichte des Museums". Museum für Naturkunde (in German). Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Behörden, Kirchen und Schulen, öffentliche Einrichtungen von Berlin". zlb.de. Berliner Adreßbuch. p. 8.

- ^ "Naturkundemuseum: Schatzkammer aus Glas". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Wettbewerbe-aktuell. "Ausschreibung: Museum für Naturkunde". www.wettbewerbe-aktuell.de (in German). Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Investition in Berliner Wissenschaft: Wie das Naturkundemuseum an die Millionen kam". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Sentker, Andreas (16 November 2018). "Naturkundemuseum Berlin: Von Insekten lernen heißt überleben lernen". Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Ronzheimer, Manfred (23 November 2018). "Ein ganz dicker Happen". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). p. 23. ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Olshevsky, G. (1991). "A Revision of the Parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, Excluding the Advanced Crocodylia". Mesozoic Meanderings #2. 1 (4): 196 pp.

- Paul, G. S. (1988). "The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world's largest dinosaurs". Hunteria. 2 (3): 1–14.

- Maier, Gerhard. African dinosaurs unearthed: the Tendaguru expeditions. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2003. (Life of the Past Series).

- Damaschun, F., Böhme, G. & H. Landsberg, 2000. Naturkundliche Museen der Berliner Universität – Museum für Naturkunde: 190 Jahre Sammeln und Forschen. 86–106.— In: H. Bredekamp, J. Brüning & C. Weber (eds.). Theater der Natur und Kunst Theatrum Naturae et Artis. Essays Wunderkammern des Wissens, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin & Henschel Verlag. 1–280. Berlin.

- Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; Bussert, Robert; Aberhan, Martin (2011). "A blast from the past: the lost world of dinosaurs at Tendaguru, East Africa". Geology Today. 27 (3). Wiley: 101–106. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2011.00795.x. ISSN 0266-6979. S2CID 128697039.

External links

[edit]- Museums in Berlin

- Natural history museums in Germany

- Mineralogy museums

- Shell museums

- Geology museums in Germany

- Museums established in 1810

- Humboldt University of Berlin

- University museums in Germany

- Scientists active at the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin

- 1810 establishments in Prussia

- Buildings and structures in Mitte

- Dinosaur museums