Moxidectin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cydectin, Equest, ProHeart, Quest.[1] |

| Other names | CL 301,423;[2] milbemycin B.[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, topical, subcutaneous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.163.046 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

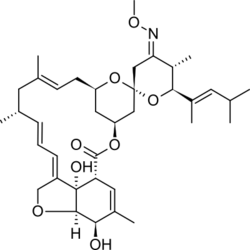

| Formula | C37H53NO8 |

| Molar mass | 639.830 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Moxidectin is an anthelmintic drug used in animals to prevent or control parasitic worms (helminths), such as heartworm and intestinal worms, in dogs, cats, horses, cattle, sheep and wombats.[4] Moxidectin kills some of the most common internal and external parasites by selectively binding to a parasite's glutamate-gated chloride ion channels. These channels are vital to the function of invertebrate nerve and muscle cells; when moxidectin binds to the channels, it disrupts neurotransmission, resulting in paralysis and death of the parasite.

Medical uses

[edit]Moxidectin was approved for onchocerciasis (river-blindness) in 2018 for people over the age of 11 in the United States based on two studies.[5] There is a need for additional trials, with long-term follow-up, to assess whether moxidectin is safe and effective for treatment of nematode infection in children and women of childbearing potential.[6] Moxidectin is predicted to be helpful to achieve elimination goals of this disease.[7]

- Dogs: Prevention of heartworm. In combination with imidacloprid to treat sarcoptic mange.[8]

- Horses: Treatment of parasites including Strongylus vulgaris, and stomach bots such as Gasterophilus intestinalis.[9]

- Cattle: Treatment of parasites such as the gastrointestinal nematode Ostertagia ostertagi, and the lungworm Dictyocaulus viviparus.[1]

- Sheep: Treatment of the nematodes Teladorsagia circumcincta and Haemonchus contortus.[10]

Nematodes can develop cross-resistance between moxidectin and other similar parasiticides, such as ivermectin, doramectin and abamectin.[11] The ways in which the parasites evolve resistance to this drug include mutations in glutamate-gated chloride channel genes, GABA-R genes,[12] or increased expression of p-glycoprotein, which is a transmembrane drug efflux pump.[13] Allele frequency changes corresponding to resistance to moxidectin and/or other macrocyclic lactone-class drugs have been observed in the glutamate-gated chloride channel α-subunit gene of Haemonchus contortus and Cooperia oncophora, as well as in the H. contortus genes coding for p-glycoprotein and the GABA-R gene.[13]

Moxidectin is being evaluated as a treatment to eradicate scabies in humans, especially when resistant to other treatments.[14]

Adverse effects

[edit]Studies of moxidectin show the side effects vary by animal and may be affected by the product's formulation, application method and dosage.[citation needed]. It is however regarded as relatively safe.[15]

An overdose of moxidectin enhances the effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the central nervous system.[16] In horses, overdose may lead to depression, drooping of the lower lip, tremor, lack of coordination when moving (ataxia), decreased rate of breathing (respiratory rate), stupor and coma.[16]

If a dog licks moxidectin from the skin which was applied as a "spot-on" (topical) treatment, this has the same effect as an overdose, and may cause vomiting, salivation and neurological signs such as ataxia, tremor, and nystagmus.[8] Some Collie dogs can tolerate moxidectin, but other individuals are sensitive and upon ingestion, experience vomiting, salivation or transient neurological signs.[8]

Pharmacology

[edit]Moxidectin is very lipophilic, which causes it to have a high volume of distribution.[17] Moxidectin concentrates in the animal's adipose tissue, from where it is released for up to two months following administration.[17]

In goats, the oral bioavailability of moxidectin is 2.7 times lower, and the half-life is 1.8 times shorter than in sheep.[18]

Chemistry

[edit]Moxidectin, a macrocyclic lactone of the milbemycin class,[8] is a semisynthetic derivative of nemadectin, which is a fermentation product of the bacterium Streptomyces cyanogriseus subsp. noncyanogenus.[19]

History

[edit]In the late 1980s, an American Cyanamid Company agronomist discovered the Streptomyces bacteria from which moxidectin is derived in a soil sample from Australia. Two companies filed patents for moxidectin: Glaxo Group and the American Cyanamid Company;[1] in 1988, all patents were transferred to American Cyanamid.[1] In 1990, the first moxidectin product was sold in Argentina.[1]

For human use, moxidectin was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in June 2018 for the treatment of onchocerciasis in adults and adolescents aged 12 and older. This is the first human approval worldwide. The license holder is the nonprofit biopharmaceutical company Medicines Development for Global Health.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Awasthi A, Razzak M, Al-Kassas R, Harvey J, Garg S (2013). "Chapter 7: Analytical profile of moxidectin". In Brittain H (ed.). Profiles of drug substances, excipients and related methodology: Volume 38. Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 315–366. ISBN 9780124078284.

- ^ a b "milbemycin". MeSH - NCBI. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Cydectin Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Old JM, Skelton C, Stannard HJ (2021). "The use of Cydectin® by wildlife carers to treat sarcoptic mange in free-ranging bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus)". Parasitology Research. 120 (3): 1077–1090. doi:10.1007/s00436-020-07012-8. PMID 33438043.

- ^ Awadzi K, Opoku NO, Attah SK, Lazdins-Helds J, Kuesel AC (June 2014). "A randomized, single-ascending-dose, ivermectin-controlled, double-blind study of moxidectin in Onchocerca volvulus infection". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (6): e2953. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002953. PMC 4072596. PMID 24968000.

- ^ Maheu-Giroux M, Joseph SA (August 2018). "Moxidectin for deworming: from trials to implementation". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 18 (8): 817–819. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30270-6. PMID 29858152. S2CID 46921091.

- ^ Turner HC, Walker M, Attah SK, Opoku NO, Awadzi K, Kuesel AC, et al. (March 2015). "The potential impact of moxidectin on onchocerciasis elimination in Africa: an economic evaluation based on the Phase II clinical trial data". Parasites & Vectors. 8: 167. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0779-4. PMC 4381491. PMID 25889256.

- ^ a b c d Patel A, Forsythe P (2008). Small animal dermatology. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 26. ISBN 9780702028700.

- ^ Papich MG (2011). "Moxidectin". Saunders handbook of veterinary drugs small and large animal (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 525–526. ISBN 9781437701920.

- ^ Sargison N (2008). "Moxidectin". Sheep flock health a planned approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9781444302608.

- ^ Rugg D, Buckingham SD, Sattelle DB, Jansson RK (2010). "The insecticidal macrocyclic lactones". In Gilbert GI, Gill SS (eds.). Insect pharmacology channels, receptors, toxins and enzymes. London: Academic Press. ISBN 9780123814487.

- ^ Wolstenholme AJ, Fairweather I, Prichard R, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Sangster NC (October 2004). "Drug resistance in veterinary helminths". Trends in Parasitology. 20 (10): 469–476. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.010. PMID 15363440.

- ^ a b Blackhall WJ, Prichard RK, Beech RN (March 2008). "P-glycoprotein selection in strains of Haemonchus contortus resistant to benzimidazoles". Veterinary Parasitology. 152 (1–2): 101–107. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.12.001. PMID 18241994.

- ^ Mounsey KE, Bernigaud C, Chosidow O, McCarthy JS (March 2016). "Prospects for Moxidectin as a New Oral Treatment for Human Scabies". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (3): e0004389. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004389. PMC 4795782. PMID 26985995.

- ^ Schraven AL, Stannard HJ, Old JM (2021). "A systematic review of moxidectin as a treatment for parasitic infections in mammalian species". Parasitology Research. 120 (4): 1167–1181. doi:10.1007/s00436-021-07092-0. PMID 33615411.

- ^ a b Dowling PM (2012). "Ivermectin and moxidectin toxicosis". In Wilson DA (ed.). Clinical veterinary advisor: The horse. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 307–308. ISBN 9781437714494.

- ^ a b Lanusse CE, Lifschitz AL, Imperiale FA (2013). "Chapter 42: Macrocyclic lactones: Endectocide compounds". In Riviere JE, Papich MG (eds.). Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 1126. ISBN 978-1118685907.

- ^ Baynes RE, Payne M, Martin-Jimenez T, Abdullah AR, Anderson KL, Webb AI, et al. (September 2000). "Extralabel use of ivermectin and moxidectin in food animals". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 217 (5): 668–671. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.217.668. PMID 10976297.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Lumaret JP, Errouissi F, Floate K, Römbke J, Wardhaugh K (May 2012). "A review on the toxicity and non-target effects of macrocyclic lactones in terrestrial and aquatic environments". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 13 (6): 1004–1060. doi:10.2174/138920112800399257. PMC 3409360. PMID 22039795.

- ^ "MOXIDECTIN tablet". Dailymed. U.S. National Library of Medicine.