Mount Price (British Columbia)

| Mount Price | |

|---|---|

| Red Mountain Clinker Mountain | |

Mount Price behind Garibaldi Lake from Panorama Ridge | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,049 m (6,722 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 49°55′03″N 123°02′08″W / 49.91750°N 123.03556°W[2] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Thomas E. Price[2] |

| Geography | |

| Country | Canada[3] |

| Province | British Columbia[3] |

| District | New Westminster Land District[2] |

| Protected area | Garibaldi Provincial Park[4] |

| Parent range | Garibaldi Ranges |

| Topo map | NTS 92G14 Cheakamus River[2] |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Less than 1.2 million years old[3] |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano[1] |

| Rock type(s) | Andesite and dacite[3] |

| Volcanic belt | Garibaldi Volcanic Belt[3] |

| Last eruption | 15,000–8,000 years ago[5][6] |

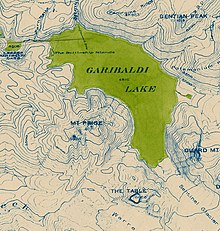

Mount Price is a small stratovolcano in the Garibaldi Ranges of the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It has an elevation of 2,049 metres (6,722 feet) and rises above the surrounding landscape on the western side of Garibaldi Lake in New Westminster Land District. The mountain contains a number of subfeatures, including Clinker Peak on its western flank, which was the source of two thick lava flows between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago that ponded against glacial ice. These lava flows are structurally unstable, having produced large landslides as recently as the 1850s. A large provincial park surrounds Mount Price and other volcanoes in its vicinity. It lies within an ecological region that surrounds much of the Pacific Ranges.

Mount Price is associated with a small group of volcanoes called the Garibaldi Lake volcanic field. This forms part of the larger Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, a north−south trending volcanic zone that represents a portion of the Canadian Cascade Arc. Mount Price began its formation 1.2 million years ago and continued intermittently until sometime in the last 15,000 years. Although the mountain is not known to have been volcanically active for thousands of years, it could erupt again, which would potentially endanger the nearby populace. If this were to happen, relief efforts could be organized by teams such as the Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan who are prepared to notify people threatened by volcanic eruptions in Canada.

Geography

[edit]Mount Price is located south of Whistler on the western side of Garibaldi Lake in New Westminster Land District.[2] It lies within the Pacific Ranges Ecoregion, a mountainous region of the southern Coast Mountains characterized by high, steep and rugged mountains made of granitic rocks. Much of this ecoregion encompasses the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, although it also includes the northwesternmost portion of the Cascade Range in Washington state. Several coastal islands, channels and fjords occur along the western margin of the Pacific Ranges Ecoregion. The Pacific Ranges Ecoregion is part of the Coast and Mountains Ecoprovince which forms part of the Humid Maritime and Highlands Ecodivision.[7]

The Pacific Ranges Ecoregion is subdivided into seven ecosections, the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection being the main ecosection at Mount Price. This ecosection is characterized by a rugged landscape of mountains that increase in elevation from south to north; the northern summits contain large icefields. A transitional climate between coastal maritime and interior continental climates dominates the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection. It is characterized by little precipitation and mild temperatures due to Pacific air often passing over this area. During winter, cold Arctic air invades from the Central Interior, resulting in extreme cloud cover and snow. A number of other volcanoes are situated within the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection. This includes Mount Meager, which lies near the headwaters of the Lillooet River, and Mount Garibaldi and Mount Cayley, which lie in the Squamish River watershed.[7]

Several rivers flow through the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection, including the Fraser and Coquihalla rivers on its eastern side, the Cheakamus, Squamish and Elaho rivers on its western side and the Lillooet River in the middle. Coastal western hemlock forests dominate nearly all the valleys and lower slopes of this ecosection, the upper slopes containing subalpine mountain hemlock forests and, to a lesser extent, Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir forests. Alpine vegetation lies just above the subalpine forests, which is normally overlain by barren rock.[7] Wildlife such as grey jays, chipmunks, squirrels, flickers, deer, mountain goats, wolverines, cougars and grizzly and black bears are locally present.[8] The communities of Whistler, Pemberton, Mount Currie, Hope and Yale are situated within the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection, all of which are connected to the Lower Mainland by a network of highways.[7]

Geology

[edit]

Mount Price is one of the three principal volcanoes in the southern segment of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, the other two being Mount Garibaldi and The Black Tusk.[3] Mount Price is also part of the Garibaldi Lake volcanic field. This consists of several volcanoes and lava flows that formed in the last 1.3 million years; the oldest volcanic rocks are found at Mount Price and The Black Tusk. Several volcanic rocks with differing compositions are present in the Garibaldi Lake volcanic field. This includes andesite, dacite, basaltic andesite and basalt.[3] It is unknown when the last eruption occurred but it may have been in the early Holocene.[a][1][3] Although no hot springs are known in the Garibaldi area, there is evidence of anomalously high heat flow in Table Meadows just south of Mount Price and elsewhere.[10]

Like other volcanoes in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, Mount Price formed as a result of subduction zone volcanism. As the Juan de Fuca Plate thrusts under the North American Plate at the Cascadia subduction zone, it forms volcanoes and volcanic eruptions.[11] Unlike most subduction zones worldwide, there is no deep oceanic trench along the continental margin of Cascadia. There is also very little seismic evidence that the Juan de Fuca Plate is actively subducting. The probable explanation lies in the rate of convergence between the Juan de Fuca and North American plates. These two tectonic plates currently converge at a rate of 3 to 4 centimetres (1.2 to 1.6 inches) per year, only about half the rate of convergence from seven million years ago. This slowed convergence likely accounts for reduced seismicity and the lack of an oceanic trench. The best evidence for ongoing subduction is the existence of active volcanism in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.[3]

Structure

[edit]

Mount Price attains an elevation of 2,049 metres (6,722 feet) and is one of several Garibaldi Belt volcanoes that have been volcanically active throughout the Quaternary.[b][1][3] In contrast to most stratovolcanoes in Canada, Mount Price has a nearly symmetrical structure.[3] Its western slope is flanked by Clinker Peak, a 1,983-metre-high (6,506-foot) parasitic stratovolcano containing a breached volcanic crater.[1][3] Oxidation of Mount Price's volcanic rocks has given the mountain a red colour.[12]

Mount Price stands within a cirque-like basin cut into the plateau on the south side of the valley of Garibaldi Lake. This basin consists of a wall of granite, inclosing the volcano on its west and southwest sides. It is now almost completely filled up by Mount Price, but some small areas of its floor are exposed on the north side. The basin likely formed as a result of glacial action as its north side appears to have been almost certainly glaciated. It might otherwise have been attributed to explosive volcanism, but there are no fragmental materials around its margin which would confirm this.[13]

Volcanic history

[edit]At least three phases of eruptive activity have been identified at Mount Price.[3] The first eruptive phase 1.2 million years ago deposited hornblende[c] andesite lava and pyroclastic rocks on the floor of the cirque-like basin after an Early Pleistocene[d] glacial event.[3][16] During the Middle Pleistocene[e] about 300,000 years ago, volcanism of the second phase shifted westward and constructed the nearly symmetrical stratovolcano of Mount Price. Episodic eruptions during this phase of activity produced andesite and dacite lavas, as well as pyroclastic flows from Peléan activity. Later, the volcano was overridden by the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which covered a large portion of western North America during glacial periods of the Quaternary.[3]

After the Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreated from higher elevations less than 15,000 years ago, andesite eruptions of the third eruptive phase occurred from a satellite vent at Price Bay.[3][5][16] These eruptions resulted in the creation of a small lava dome or scoria cone on Mount Price's northern flank with an elevation of 1,788 metres (5,866 feet).[1][5][16] Possibly contemporaneous volcanism occurred at Clinker Peak with the eruption of two hornblende-biotite[f] andesite lava flows.[3] They are both at least 300 metres (980 feet) thick and 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) long, extending to the northwest and southwest.[3][16] Their unusually large thickness is due to them ponding and cooling against the Cordilleran Ice Sheet when it still filled valleys at lower elevations.[16] Age estimates for this final volcanic phase have varied from 15,000 years ago to as recently as 8,000 years ago.[5][6]

A prominent feature of the Clinker Peak lava flows are the levees that demarcate the lava channels. The northwest lava flow forms a volcanic dam known as The Barrier.[19] This retains the Garibaldi Lake system and has been the source of two large landslides in the past. The most recent major landslide in 1855–1856 resulted from failure along vertical rock fractures.[20] It travelled 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) down Rubble Creek to the Cheakamus River valley, depositing 30,000,000 cubic metres (1.1×109 cubic feet) of rock.[20][21] The southwest lava flow is in the upper reaches of the Culliton Creek valley and forms Clinker Ridge.[6][19] Both lava flows form steep cliffs; the current face of The Barrier is a result of the mid-19th century landslide.[6]

Volcanic hazards

[edit]

Mount Price is one of the four highest threat volcanoes in Canada situated within close proximity to major populations with critical civil and economic infrastructure, the other three being Mount Meager, Mount Garibaldi and Mount Cayley.[22] Although Plinian eruptions have not been identified at Mount Price, Peléan eruptions can also produce large amounts of volcanic ash that could significantly affect the nearby communities of Whistler and Squamish. Peléan eruptions might cause short and long term water supply problems for the city of Vancouver and most of the Lower Mainland. The catchment area for the Greater Vancouver watershed is downwind from Mount Price. An eruption producing floods and lahars could destroy parts of Highway 99, threaten communities such as Brackendale and endanger water supplies from Pitt Lake. Fisheries on the Pitt River would also be at risk.[19] Mount Price is also close to a major air traffic route; volcanic ash reduces visibility and can cause jet engine failure, as well as damage to other aircraft systems.[23][24] These volcanic hazards become more serious as the Lower Mainland grows in population.[19]

Because andesite is the main type of lava erupted from Mount Price, lava flows are a low to moderate hazard.[19] Andesite is intermediate in silica content, indicating it has a higher viscosity than basaltic lava but is less viscous than dacite or rhyolite lava. As a result, andesite lava flows typically move slower than basaltic lava flows and are less likely to travel as far from their source. Dacite and rhyolite lavas are normally too viscous to flow away from a volcanic vent, resulting in the formation of lava domes.[25] An exception is the 15-kilometre-long (9.3-mile) Ring Creek dacite lava flow from Opal Cone on the southeastern flank of Mount Garibaldi, a length that is normally attained by basaltic lava flows.[19]

Concerns about The Barrier's instability due to volcanic, tectonic or heavy rainfall activity prompted the provincial government to declare the area immediately below it unsafe for human habitation in 1980.[20] This led to the evacuation of the small resort village of Garibaldi nearby and the relocation of residents to new recreational subdivisions away from the hazard zone.[19][20] The area below and adjacent to The Barrier has since been referred to as the Barrier Civil Defence Zone by BC Parks. Although landslides are unlikely to happen in the near future, warning signs are posted at the zone to make visitors aware of the potential danger and to minimize the chance of fatalities in the event of a slide. For safety reasons, BC Parks recommends visitors not to camp, stop or linger in the Barrier Civil Defence Zone.[8]

Monitoring

[edit]Like other volcanoes in the Garibaldi Lake volcanic field, Mount Price is not monitored closely enough by the Geological Survey of Canada to ascertain its activity level. The Canadian National Seismograph Network has been established to monitor earthquakes throughout Canada, but it is too far away to provide an accurate indication of activity under the mountain. It may sense an increase in seismic activity if Mount Price becomes highly restless, but this may only provide a warning for a large eruption; the system might detect activity only once the volcano has started erupting.[26] If Mount Price were to erupt, mechanisms exist to orchestrate relief efforts. The Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan was created to outline the notification procedure of some of the main agencies that would respond to an erupting volcano in Canada, an eruption close to the Canada–United States border or any eruption that would affect Canada.[27]

Human history

[edit]Protection

[edit]

Mount Price and its eruptive products lie within a conservation area called Garibaldi Provincial Park.[4] Founded in 1927 as a Class A provincial park, this wilderness park covers an area of 194,650 hectares (481,000 acres). Lying within its boundaries are a number of other volcanoes, such as Mount Garibaldi and The Black Tusk. Located 70 kilometres (43 miles) north of Vancouver in the glaciated Coast Mountains, Garibaldi Provincial Park contains diverse vegetation, iridescent waters and a rich geological history. The park also has abundant wildlife, such as squirrels, chipmunks, Canada jays and flickers. Garibaldi Provincial Park is named after Mount Garibaldi, which is in turn named after the Italian patriot and soldier Giuseppe Garibaldi.[8]

Naming

[edit]Mount Price has had at least three names throughout its history. It was originally named Red Mountain for its red appearance, but the date when this name was adopted has not been cited.[2] Another peak west of Overlord Mountain was identified as Red Mountain on a 1923 sketch by Canadian mountaineer Neal M. Carter.[28][29] To avoid confusion, the name of that mountain was changed to Fissile Peak on September 2, 1930, for its fissility.[2][28] In 1952, Canadian volcanologist William Henry Mathews identified Mount Price as Clinker Mountain in the American Journal of Science.[30] Clinker is a geological term used to describe rough lava fragments associated with 'a'a flows. The fragments are characterized by several sharp, jagged spines and are normally less than 150 millimetres (5.9 inches) wide.[31]

The name Mount Price appeared on a topographic map of Garibaldi Provincial Park in 1928.[32] It later appeared on National Topographic System maps 92G and 92J in 1930 after a committee of the Garibaldi Park Board was set up to deal with nomenclature. The committee requested that the Geographic Board of Canada adopt the name Mount Price for this mountain after Thomas E. Price, a former mountaineer and engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway who was a member of the Garibaldi Park Board at the time of the park's formation in 1927. Price was born at Vancouver in 1887 and was a member of a mountaineering party that had climbed Mount Garibaldi by a new route in 1908.[2] Clinker Peak and Clinker Ridge were both officially named on September 12, 1972, to retain Mount Price's earlier name, Clinker Mountain.[33][34]

Geological studies

[edit]The Clinker Peak lava flows were one of the first described occurrences of lava having been impounded by glacial ice.[35] They were the subject of significant study by William Henry Mathews, a pioneer in the study of subglacial eruptions and volcano-ice interactions in North America. In 1952, Mathews cited substantial evidence supporting the conclusion that the Clinker Peak lava flows ponded against glacial ice. This included the existence of glacially striated boulders in the lava flows, conformable relations with glacial till, abnormal structures indicative of extrusion into standing meltwater or against ice, and widespread breccia and pillows indicative of rapid quenching in meltwater or in water-soaked pyroclastic rocks under the ice.[30]

Accessibility

[edit]Daisy Lake Road, 30 kilometres (19 miles) north of Squamish, provides access to Garibaldi Provincial Park from Highway 99.[3][36] At the end of this 2.5-kilometre-long (1.6-mile) road is the Rubble Creek parking lot from which the 9-kilometre-long (5.6-mile) Garibaldi Lake Trail extends to the Garibaldi Lake campground and ranger station.[3][4][36][37] A 5-kilometre-long (3.1-mile) hiking trail, known as the Mount Price Trail or the Mount Price Route, commences past the ranger station.[4][38][37] This poorly marked path ascends to the shore of Garibaldi Lake and then returns inland where it traverses south along the lava flow forming The Barrier. The terrain of this part of the route is relatively rough, involving substantial scrambling over boulders of the lava flow. Eventually the trail reaches open terrain north of Mount Price and approaches the base of the volcano. Climbing Mount Price or Clinker Peak involves scree and snow plodding; both peaks do not require scrambling.[4]

See also

[edit]- List of mountains of British Columbia

- List of volcanoes in Canada

- List of Cascade volcanoes

- Volcanism of Western Canada

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Holocene is the current geologic epoch, which began 11,700 years ago.[9]

- ^ The Quaternary is the current geologic period, which began 2.58 million years ago.[9]

- ^ Hornblende is a green to black amphibole mineral common in igneous and metamorphic rocks.[14]

- ^ The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch that spans the Gelasian and Calabrian stages, which together cover a timespan ranging from 2.58 to 0.774 million years ago.[9][15]

- ^ The Middle Pleistocene is a synonymous term for the Chibanian stage, which spans the time between 774,000 and 129,000 years ago.[9][17]

- ^ Biotite is a dark green, black or brown mineral of the mica group.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Garibaldi Lake: Synonyms & Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Mount Price". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (1990). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–114, 143–144, 148. ISBN 0-521-43811-X. OCLC 1251392896.

- ^ a b c d e Hui, Stephen (2018). "Hikes North of Vancouver". 105 Hikes In and Around Southwestern British Columbia. Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1771642873.

- ^ a b c d Hildreth, Wes (2007). Quaternary Magmatism in the Cascades – Geologic Perspectives (PDF). United States Geological Survey. p. 67. ISBN 978-1411319455. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Russel, J. K.; Hickson, C. J.; Andrews, Graham (2007). "Canadian Cascade volcanism: Subglacial to explosive eruptions along the Sea to Sky Corridor, British Columbia". In Stelling, Pete; Tucker, David S. (eds.). Floods, Faults, and Fire: Geological Field Trips in Washington State and Southwest British Columbia. GSA Field Guides. Vol. 9. Geological Society of America. p. 12. doi:10.1130/2007.fld009(01). ISBN 978-0813700090.

- ^ a b c d Demarchi, Dennis A. (2011). An Introduction to the Ecoregions of British Columbia (PDF). Government of British Columbia. pp. 24, 25, 37, 38, 39, 47, 56, 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Garibaldi Provincial Park". BC Parks. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Woodsworth, Glenn J. (April 2003). Geology and Geothermal Potantial of the AWA Claim Group, Squamish, British Columbia (PDF) (Report). Government of British Columbia. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Garibaldi volcanic belt". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. April 2, 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Smellie, J. L.; Chapman, M. G. (2002). Volcano-Ice Interaction on Earth and Mars. Geological Society of London. p. 202. ISBN 978-1862391215. OCLC 879065355.

- ^ Burwash, Edward M. (1914). "Pleistocene Vulcanism of the Coast Range of British Columbia". The Journal of Geology. 22 (3). University of Chicago Press: 262, 263. doi:10.1086/622148. S2CID 128978632.

- ^ Bucksch, Herbert (2013). Dictionary Geotechnical Engineering / Wörterbuch GeoTechnik. Vol. 1. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 308. ISBN 978-3662033265.

- ^ Martin, C. J.; Griffiths, James S. (2017). Engineering Geology and Geomorphology of Glaciated and Periglaciated Terrains. Geological Society of London. p. 33. ISBN 978-1786203021.

- ^ a b c d e Green, Nathan L. (1990). "Late Cenozoic Volcanism in the Mount Garibaldi and Garibaldi Lake Volcanic Fields, Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, Southwestern British Columbia". Geoscience Canada. 17 (3). Geological Association of Canada: 172, 173. ISSN 1911-4850.

- ^ Tobratov, Sergei A.; Zheleznova, Olga S. (2020). "Experience of Large-Scale Analysis of the Spatial Patterns of Plain Forest Ecosystem Productivity and Biogeochemical Processes". In Frank-Kamenetskaya, Olga V.; Vlasov, Dmitry Yu.; Panova, Elena G.; Lessovaia, Sofia N. (eds.). Processes and Phenomena on the Boundary Between Biogenic and Abiogenic Nature. Springer Nature. p. 324. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-21614-6_18. ISBN 978-3030216139.

- ^ West, Terry R.; Shakoor, Abdul (2018). "Minerals". Geology Applied to Engineering. Waveland Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1478635000.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Garibaldi volcanic belt: Garibaldi Lake volcanic field". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Evans, S.G.; Savigny, K.W. (1994). "Landslides in the Vancouver-Fraser Valley-Whistler region". Geology and Geological Hazards of the Vancouver Region, Southwestern British Columbia. Natural Resources Canada. pp. 268, 270. ISBN 978-0660157849. OCLC 32231242.

- ^ "Where do landslides occur?". Government of British Columbia. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Alexander M.; Kelman, Melanie C. (2021). Assessing the relative threats from Canadian volcanoes (Report). Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 8790. Natural Resources Canada. p. 50. doi:10.4095/328950.

- ^ "Volcanic hazards". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. April 2, 2009. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Neal, Christina A.; Casadevall, Thomas J.; Miller, Thomas P.; Hendley II, James W.; Stauffer, Peter H. (October 14, 2004). "Volcanic Ash–Danger to Aircraft in the North Pacific". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ "Lava flows destroy everything in their path". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Monitoring volcanoes". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. February 26, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan (IVENP)". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Fissile Peak". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Scott, Chic (2000). Pushing the Limits: The Story of Canadian Mountaineering. Rocky Mountain Books. p. 122. ISBN 978-0921102595. OCLC 45707893.

- ^ a b Mathews, W. H. (1952). "Ice-dammed lavas from Clinker Mountain, southwestern British Columbia". American Journal of Science. 250 (8). American Journal of Science: 553–565. Bibcode:1952AmJS..250..553M. doi:10.2475/AJS.250.8.553. S2CID 131690276.

- ^ Bell, F. G. (1983). Fundamentals of Engineering Geology. Butterworth & Company. p. 17. ISBN 978-0408011693. OCLC 10243882.

- ^ Campbell, A. J. (1928). Topographical Map of Garibaldi Park (Map). 1:40,000. British Columbia Department of Lands. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Clinker Peak". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "Clinker Ridge". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Wilson, A. M.; Russell, J. K. (2019). "Quaternary glaciovolcanism in the Canadian Cascade volcanic arc – Paleoenvironmental implications". In Poland, Michael P.; Garcia, Michael O.; Camp, Victor E.; Grunder, Anita (eds.). Field Volcanology: A Tribute to the Distinguished Career of Don Swanson. GSA Special Papers. Vol. 538. Geological Society of America. p. 141. doi:10.1130/2018.2538(06). ISBN 978-0813795386. S2CID 214521258.

- ^ a b Eyton, Taryn (2021). "Garibaldi Lake and Taylor Meadows". Backpacking in Southwestern British Columbia: The Essential Guide to Overnight Hiking Trips. Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1771646697.

- ^ a b Anderson, Sean; Bryant, Leslie; Harris, Brian; Hoare, Jay; Hughes, Colin; Manyk, Mike; Mussio, Russell; Soroka, Stepan (2019). Vancouver, Coast & Mountains BC. Mussio Ventures. p. 135. ISBN 978-1926806952.

- ^ "Hut Management Plan 2019" (PDF). University of British Columbia. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

External links

[edit]- "Mount Price". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- "Mount Price". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- "Clinker Peak". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- "Clinker Peak". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2021.