Moses Yale Beach

Moses Yale Beach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 15, 1800[1] |

| Died | July 19, 1868 (aged 68) |

| Known for | New York Sun Associated Press |

| Children | Alfred Ely Beach Moses S. Beach William Yale Beach |

| Relatives | Elihu Yale, cousin James Murray Yale, cousin Arthur Yale, cousin William Yale, cousin Edwin R. Yale, cousin Frederick C. Beach, grandson Charles Yale Beach, grandson Emma Beach Thayer, granddaughter Stanley Yale Beach, great-grandson Brewster Yale Beach, great-great-grandson |

| Family | Yale |

| Signature | |

| |

Moses Yale Beach (January 15, 1800 – July 19, 1868)[2] was an American inventor, entrepreneur, philanthropist and publisher, who founded the Associated Press, and is credited with originating print syndication.[3][4] His fortune, as of 1846, amounted to $300,000 ($10.2 million in 2023), which was about 1/4 of the fortune of Cornelius Vanderbilt at the time, and was featured in a book that he published named the Wealthy citizens of the City of New York.[5]

His newspaper, the New York Sun, became the most successful newspaper in America, and was a pioneer on crime reporting and human-interest stories for the masses.[6][7][8][9]

Biography

[edit]

Moses was born in Wallingford, Connecticut, to Moses Sperry Beach and Lucretia Yale, and was a cousin of Canadian fur trader James Murray Yale and Gov. Elihu Yale of Yale University, members of the Yale family.[10][11] Merchant William Yale and Gen. Edwin R. Yale were second cousins, while Linus Yale Sr. and Linus Yale Jr., of the Yale Lock Company, were fourth cousins.[12] His grandfather, Capt. Elihu Yale, son of Capt. Theophilus Yale, was one of the first bayonet manufacturer in Connecticut during the American Revolutionary War, and one of the largest landholders of Wallingford.[13][14]

His father was a plain farmer, and gave him an ordinary education. As a boy, he was a fifer in the War of 1812 at Fort Nathan Hale.[15] He showed a mechanical aptitude from an early age, and at 14 was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker. Before his term was up, he purchased his freedom and established a cabinet-making business in Northampton, Massachusetts, competing with John Holbrook, father of Gov. Holbrook.[16] The business failed, and he moved to Springfield. There he endeavoured to manufacture a gunpowder engine for propelling balloons; but this enterprise was also a failure.

He was among the first to invest in paddle steamships to open steam navigation on the Connecticut river between Hartford and Springfield, and would have succeeded if financial difficulties had not obliged him to cease operations before his steamer was completed.[17] This venture was in association with Thomas Blanchard, the inventor of America's first assembly line in 1819, and inventor of the first American automobile in 1826.[18][19] He then invented a rag-cutting machine for paper mills.

The invention was widely used, but Moses derived no pecuniary benefit due to his tardiness in applying for a patent. He then settled in Ulster County, New York, where he invested in an extensive paper mill. At first he was successful, and after six years was wealthy; but after seven years, an imprudent investment dispersed his fortune, and was compelled to abandon his enterprise. In 1829, he became one of the trustees of Saugerties, N.Y., organizing their fire department, and purchased the first fire engine of the city.[20] In the meantime though, he had married the sister of Benjamin Day, founder and proprietor of the New York Sun.

In 1835, he acquired an interest in the paper from George W. Wisner, an early founder who had been in charge of reporting police news and writing police reports, being the first to do so in the industry.[21] His brother was Gov. Moses Wisner, a member of the family of Patriot Henry Wisner, a gunpowder manufacturer for George Washington during the Revolutionary War. After selling his shares, he would go back to Michigan and found his own journal. The Sun was then small, both in the size of its sheet and circulation, and with a $40,000 payment, Moses soon became sole proprietor, acquiring the shares of Benjamin Day and Mr. Wisner.

New York Sun

[edit]

The New York Sun, as a penny press journal, brought many innovations to the industry, such as being the first U.S. journal to hire a Police reporter.[22][23] They were also the first newspaper to report crimes and personal events such as suicides, deaths, and divorces, which featured everyday people rather than public figures. As the early developers of the craft of reporting and storytelling, they changed journalism, and brought a new business model focused on mass-production and advertising rather than subscriptions. With the breakthrough of selling their newspaper for a penny, a very low price affordable to most, it got New Yorkers from all walks of life reading the news and stay informed. They also launched hoaxes with the aim of attracting attention, such as the Great Moon Hoax of 1835 or The Balloon-Hoax.[24] Theses innovations led the journal to eventually become the most successful newspaper in America.[25]

James Gordon Bennett Sr., intrigued by the success of the New York Sun, would go on and copy the paper and found his own journal in 1835, naming it the New York Herald.[26] Through his 10 years of proprietorship, Moses would expand the four-page paper from three to eight columns. He would also develop horse, rail, and pigeon services to accelerate the speed of news-gathering into his New York offices.[27] He established a ship news service in association with other organizations to obtain news from Europe, acquiring the steamboat "Naushon".[28][29][30]

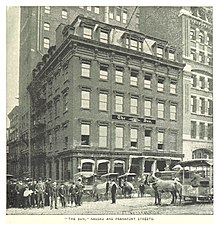

The "Pony Express" horses brought important news from Albany, and he ran special trains that ran from Baltimore to speed up their arrival.[31] His pigeon house was built on the roof of his New York office at Nassau Street to bring news from nearby ports.[32] An important competitor was Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune. The "Commodore Vanderbilt" used the newspaper to advertise his steamship sailings from New York to Hartford, charging one dollar a passenger to get aboard his steamboat the "Water Witch".[33]

According to historian Elmo Scott Watson, Moses invented print syndication in 1841 when he produced a two-page supplement and sold it to a score of newspapers in the U.S. northeast.[35] He became the major shareholder in four banks and started being a banker himself, establishing banks in the states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Florida.[36][37] He also later acquired the American book publishing company Harper Brothers, and established the "American Sun" in Europe, the "Weekly Sun" for farmers, and the "Illustrated Sun and Monthly Literary Journal".[38][39]

In 1842, he published the first directory of wealthy Americans called the Wealth and Pedigree of Wealthy Citizens of New York City.[40] In the 1846 edition, Moses Yale Beach was featured with a fortune of US$300,000, which translates to 3.3 billion dollars in 2022 money in relation to GDP, and was featured along with Cornelius Vanderbilt at 1.2 million, and John Jacob Astor at 25 millions, the richest man in the world at the time.[41] In 1846, only fourteen individuals were millionaires in New York, with a population of about 500,000 people, making Moses Yale Beach among the richest men in the city.[42]

From 1843 to 1847, Moses grew the newspaper, employing 8 editors and reporters, 16 pressmen, 12 female folders, and 100 newsboy.[45] In the same year, he was appointed United States Ambassador to Mexico, and named Special Diplomatic Agent by U.S. President John Tyler. He was also a representative of New York's bankers for the war mission, and a director of several New York banks, carrying with him $50,000 to establish a National Bank in Mexico.[46]

He cofounded the Harbor News Association in association with other newspapers and Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph, and the New York Associated Press, implicating robber baron Jay Gould. In May 1846, Moses founded the Associated Press[47][48] (at that time publisher of The Sun), and was joined by the New York Herald, the New York Courier, The Journal of Commerce, and the New York Evening Express.[49] The AP had been formed by the five New York daily papers to share the cost of transmitting news of the Mexican–American War.[50] It became the oldest and largest news agency in the United States, and the largest in the world.[51] Their offices would later be at 50 Rockefeller Plaza, formerly known as the Associated Press Building, and be part of Rockefeller Center.

Mexican-American War

[edit]

During the Mexican–American War, Moses went on a trip to Washington where he met with Secretary of State James Buchanan and U.S. President James K. Polk for talks.[52] His mission, as the President personal spy, would be to try to persuade the Mexican government to settle its ongoing war with the United States.[53][54] At the time, newspapers had better news gathering techniques than the government, having President Polk and government officials receiving the war news through their daily newspapers.[55]

As he already had a personal relationship with the former foreign minister of Mexico, Juan Almonte, President Polk sent him to Mexico to arrange a treaty of peace, bringing with him his daughter and a journalist named Jane Cazneau. Arrived on Mexican grounds, Moses received informations from General Mirabeau Lamar, the former president of the Republic of Texas, about the disenchantment of the Mexican bishops and clergy, as they were penalized by the War.[56]

He took meetings with them and tried to organize a resistance. His resistance would prove successful as the Bishops were able to raise an army of 5,000 men. The financing provided also prevented the Mexican army to counterback U.S General Winfield Scott. Following the Polkos Revolt, President Santa Anna would post a reward to capture Moses and declared that anyone found with a copy of his paper, the New York Sun, would be punished as a traitor.[57] The negotiations were eventually broken off by a false report announcing the defeat of General Zachary Taylor by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Moses returned home, along with General Scott, and eventually the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would be settled, in 1847, where the territories of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, along with parts of Texas and Arizona, would be obtained by the United States.[58] Gov. Sam Houston declared that Texas owes much to the work of Moses Yale Beach during the war.[59]

Gold Rush

[edit]

During the California Gold Rush, after talks with U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin, Moses acquired and sent the Apollo storeship with his sons Henry and Joseph to San Francisco.[60] They equipped the vessel to become a profitable business venture and created advertisements to bring passengers on board at a cost of 75$ per individual. They also brought two printing presses to establish a newspaper at the gold mines.[61] They sailed at full capacity from New York to Rio de Janeiro, then to Peru and San Francisco. Once arrived, the passengers and crew deserted the ship, attracted by California's gold.[62]

As a result, they converted the ship into a warehouse and a Saloon named the "Apollo Saloon", next to Euphemia Prison, previously owned by William Heath Davis, a vessell holding prisoners on the water in front of the establishment.[63][64] It became California's first formal insane asylum.[65] The Apollo Saloon served doughnuts, alcohol and coffee, and became a San Francisco landmark.[66] The saloon served also as a coffee house and was next to Niantic Hotel on Battery Street. It burned down two years later in 1851.

Moses was a partner in a mining venture to extract gold and quartz with P.T. Barnum of Barnum & Bailey Circus, with 2 million dollars in capital stock.[67] He also helped Barnum get the approval for Barnum's American Museum in New York and financed him.[68][69][70] The ruins of the Apollo storeship are now buried in the underground of the Old Federal Reserve Bank Building of San Francisco, and two rooms are named after the ship. Moses's son, Joseph P. Beach, would write a book about his journey named The Log of the Apollo : Joseph Perkins Beach's Journal of the Voyage of the Ship Apollo from New York to San Francisco 1849.

Personal life

[edit]

Moses retired in 1857 with an ample fortune, and left the paper to his sons. He then returned to Wallingford, Connecticut, built a luxurious Italianate house in the city, and engaged in local philanthropy.[72] The Moses Y. Beach Elementary School would later bear his name, following a land donation from him. He also gave $100,000 to the Union Army for the American Civil War, installed a 110 foot tall Liberty Pole, and gave $5,000 for St Paul's Episcopal Church reconstruction.[73] He was described as patriotic and liberal by the New York Times.[74] He died in 1868, and was buried at Center Street Cemetery, Wallingford, where a monument was erected in his memory.

Moses Yale was featured in the Pulitzer Award book "Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898" and other works, along with his son Alfred Ely, who had to bypass corrupt politicians to build New York's first subway in 1869.[75] His sons Moses Sperry and Joseph Perkins took over the New York Sun, and under their leadership, they supported Abraham Lincoln, and were described as out-and-out loyalists.[76][77][78] The paper also covered Lincoln's day of election as well as Lincoln's assassination.[79][80]

Moses Yale Beach was married twice and left six sons and two daughters :

- Alfred Ely, entrepreneur who invented New York City's first subway system, opposed by John Jacob Astor III, owner of the Scientific American magazine, founder of a school for freed slaves after the American Civil War, joined the Union League

- Moses Sperry, politician, co owner of the New York Sun and the Boston Daily Times, featured in Mark Twain's book, The Innocents Abroad, member of the New York State Assembly, visited the Czar Alexander II of the House of Romanov, supported Abraham Lincoln's policies

- As well as Eveline Shepherd, Mary Ely Day, Henry Day, Joseph Perkins, Moses Yale Beach (b. 1862), and William Yale Beach, a Freemason banker and real estate developer, doing business in the Masonic Temples of New York and Boston, among others.[81][82][83]

Moses's nephew, Clarence Day Sr., owned Gwynne & Day, a Wall Street brokerage firm seated at 40 Wall Street, and was an investment banker, railroad director, and Governor of the New York Stock Exchange.[84] His great-nephews were Yale University Treasurer George Day and Yale graduate Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and cofounders of Yale University Press.

His granddaughter Emma Beach married to artist Abbott Handerson Thayer, who pioneered the creation of the first effective forms of military camouflage, and his grandson, Charles Yale Beach, became a real estate investor. Thayer was a member of the Boston Brahmin Thayer family, and his work was mocked by Theodore Roosevelt. Emma was also the aunt of the Dean of Harvard Divinity School, William Wallace Fenn, and was a friend and possible lover of Mark Twain, and was featured in his book The Innocents Abroad.

His grandson, Frederick C. Beach, ran the family owned Scientific American Magazine, seated at the Woolworth Building, and invented a photolithographic process. The magazine is now the oldest continuously published magazine in the United States.[85][86] His great-grandson, Stanley Yale Beach, was also an aviation pioneer and airship entrepreneur, and his great-great-grandson, Brewster Yale Beach, was a Jungian psychotherapist and Episcopal minister. Stanley was a correspondent of Howard Hughes and General Billy Mitchell, father of the United States Air Force, and an early financier of another aviation pioneer, Gustave Whitehead, who claimed to have made a powered controlled airplane flight before the Wright brothers.[87][88]

References

[edit]- ^ "correct date of birth". findagrave.com. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "correct date of birth". findagrave.com. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Moses Y. Beach Obituary, New York Times, July 21, 1868, p. 2

- ^ Beach, Stanley, Archives at Yale, Stanley Yale Beach papers, Number: GEN MSS 802, 1911-1948

- ^ Moses Yale Beach (May 22, 1855). "The Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of the City of New York, Page 4 and 29". Sun office. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication, Newspapers as a Form of Mass Media; The Penny Press, Libraries Publishing

- ^ Wm. David Sloan. "George W. Wisner: Michigan Editor and Politican [sic]". tandfonline.com. doi:10.1080/00947679.1979.12066929. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "Benjamin Henry Day, American journalist and publisher". Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 5, 2022.

- ^ Bird, S. Elizabeth. For Enquiring Minds: A Cultural Study of Supermarket Tabloids. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992: 12-17.

- ^ "Yale genealogy and history of Wales : the British kings and princes, life of Owen Glyndwr, biographies of Governor Elihu Yale, for whom Yale University was named, Linus Yale, Sr". Archived.org. p. 170. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ America's successful men of affairs. An encyclopedia of contemporaneous biography, p. 66-67

- ^ "Yale genealogy and history of Wales : the British kings and princes, life of Owen Glyndwr, biographies of Governor Elihu Yale, for whom Yale University was named, Linus Yale, Sr". Archived.org. p. 170. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "Yale genealogy and history of Wales : the British kings and princes, life of Owen Glyndwr, biographies of Governor Elihu Yale, for whom Yale University was named, Linus Yale, Sr". Archived.org. pp. 142–170. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ Moses Yale Beach (May 22, 1855). "The Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of the City of New York, Page 4" (PDF). Sun office. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Charles Wells Chapin (1893). "Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century: And Its Historic Mansions of "ye Olden Tyme"". Press of Springfield Print. and Binding Company.

- ^ Chapin, Charles Wells (1893). Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield, Historic Mansions of "Ye Olden Tyme", Press of Springfield Printing and Binding Company, p. 38-39

- ^ Charles Wells Chapin (1893). "Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century: And Its Historic Mansions of "ye Olden Tyme"". Press of Springfield Print. and Binding Company.

- ^ America's successful men of affairs. An encyclopedia of contemporaneous biography, p. 66-67

- ^ Thomas Blanchard, Springfield Armory, National Historic Site, National Park Services, MassachusettsMassachusetts.

- ^ Charles Wells Chapin (1893). "Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century: And Its Historic Mansions of "ye Olden Tyme"". Press of Springfield Print. and Binding Company.

- ^ Julie Hedgepeth Williams. "The Founding of the Penny Press: Nothing New Under The Sun, The Herald or The Tribune" (PDF). Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "New York Sun, American newspaper". Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Benjamin Henry Day, American journalist and publisher". Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 5, 2022.

- ^ America's successful men of affairs. An encyclopedia of contemporaneous biography, p. 66-67

- ^ Wm. David Sloan (1979). "George W. Wisner: Michigan Editor and Politican [sic]". Journalism History. 6 (4): 113–116. doi:10.1080/00947679.1979.12066929. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Julie Hedgepeth Williams. "The Founding of the Penny Press: Nothing New Under The Sun, The Herald or The Tribune" (PDF). Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "Moses Yale Beach". Biography.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ C. Tucker, Spencer (2013.) American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ABC-CLIO, Library of Congress, p. 98-99

- ^ AP at 175: A Photographic History, Part 1: Beginnings, 1846-60, Harbor News Association contract, June 1, 1848. APCA., Valerie Komor, Director, AP Corporate Archives.

- ^ Benson John Lossing (1884).History of New York City: Embracing an Outline Sketch of Events, Volume 1., The Perine Engraving And Publishing Co., New York, p. 362

- ^ C. Tucker, Spencer (2013.) American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ABC-CLIO, Library of Congress, p. 98-99

- ^ Benson John Lossing (1884).History of New York City: Embracing an Outline Sketch of Events, Volume 1., The Perine Engraving And Publishing Co., New York, p. 362-363

- ^ Frank Michael O'Brien (1947). The Story of the Sun : New York, 1833-1918. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Benson John Lossing (1884).History of New York City: Embracing an Outline Sketch of Events, Volume 1., The Perine Engraving And Publishing Co., New York, p. 362

- ^ Watson, Elmo Scott. "CHAPTER VIII: Recent Developments in Syndicate History 1921-1935," History of Newspaper Syndicates. Archived at Stripper's Guide.

- ^ Moses Yale Beach (May 22, 1855). "The Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of the City of New York, Page 4 and 29". Sun office. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Charles Wells Chapin (1893). "Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century: And Its Historic Mansions of "ye Olden Tyme"". Press of Springfield Print. and Binding Company.

- ^ Ross Eaman (2021). Historical Dictionary of Journalism, Second Edition, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 24

- ^ Linda Sybert Hudson (1999). JANE MCMANUS STORM CAZNEAU (1807-1878): A BIOGRAPHY, University of North Texas, p. 105-106

- ^ Moses Yale Beach (May 22, 1855). "The Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of the City of New York, Page 4 and 29". Sun office. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount - 1790 to Present". MeasuringWorth.com. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. “COMMERCIAL FORTUNES IN NEW YORK: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF THE PORT OF NEW YORK ABOUT 1850.” New York History, vol. 16, no. 2, 1935, pp. 158–68. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23134861?seq=2. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023. p. 159

- ^ C. Tucker, Spencer (2013.) American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ABC-CLIO, Library of Congress, p. 98-99

- ^ AP at 175: A Photographic History, Part 1: Beginnings, 1846-60, Harbor News Association contract, June 1, 1848. APCA., Valerie Komor, Director, AP Corporate Archives.

- ^ Linda Sybert Hudson (1999). JANE MCMANUS STORM CAZNEAU (1807-1878): A BIOGRAPHY, University of North Texas, p. 105-106

- ^ Linda Sybert Hudson (1999). JANE MCMANUS STORM CAZNEAU (1807-1878): A BIOGRAPHY, University of North Texas, p. 125

- ^ Beach, Stanley, Archives at Yale, Stanley Yale Beach papers, Number: GEN MSS 802, 1911-1948

- ^ "Associated Press Founded - This Day in History May 22". New York Natives. May 22, 2015. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Press, Gil. "The Birth of Atari, Modern Computer Design, And The Software Industry: This Week In Tech History". Forbes. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Network effects". The Economist. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Associated Press, News Agency, Britannica, History & Society, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 22, 2023.

- ^ Letter from James Buchanan to Moses Beach, November 21, 1846

- ^ The works of James Buchanan, comprising his speeches, state papers, and private correspondence, Vol. VII, 1846-1848

- ^ "Moses Yale Beach: Polk's Secret Emissary to Mexico". WarfareHistoryNetwork. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Linda Sybert Hudson (1999). JANE MCMANUS STORM CAZNEAU (1807-1878): A BIOGRAPHY, University of North Texas, p. 127

- ^ "Moses Yale Beach: Polk's Secret Emissary to Mexico". WarfareHistoryNetwork. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer; Arnold, James R.; Wiener, Roberta; Pierpaoli Jr., Paul G.; Cutrer, Thomas W.; Santoni, Pedro (2013). The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War: A Political, Social, and Military History Vol1 P. 53. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781851098538. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Moses Yale Beach: Polk's Secret Emissary to Mexico". WarfareHistoryNetwork. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Charles Wells Chapin (1893). "Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century: And Its Historic Mansions of "ye Olden Tyme"". Press of Springfield Print. and Binding Company.

- ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Apollo Storeship, April 5, 1991, p. 9

- ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Apollo Storeship, April 5, 1991, p. 9-13

- ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Apollo Storeship, April 5, 1991, p. 9-13

- ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Apollo Storeship, April 5, 1991, p. 18

- ^ James P. Delgado, California History magazine, Fall 1978

- ^ James P. Delgado, California History magazine, Fall 1978

- ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Apollo Storeship, April 5, 1991, p. 9-13

- ^ Brown & Dallison's Nevada, Grass Valley and Rough and Ready Directory, p.28

- ^ Brown & Dallison's Nevada, Grass Valley and Rough and Ready Directory, p.28

- ^ History of the Museum, New York Times, July 14, 1865, p. 8

- ^ The P.T. Barnum of the Barnum and Bailey Circus by Joel Benton, Hard Times

- ^ Moses Yale Beach House, 86 North Main Street, Wallingford, New Haven County, CT Photos from Survey HABS CT-269

- ^ "Moses Yale Beach House, 86 North Main Street, Wallingford, New Haven County, CT". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Wallingford's Historic Legacy. Arcadia. 2020. ISBN 9781467104944. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ PATRIOTIC AND LIBERAL. MOSES Y. BEACH, New York Times, April 28, 1861, p. 4

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. (1999) Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, p. 640-677-700-706-932

- ^ Joseph P. Beach genealogy papers, A Guide to the Collection at the Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

- ^ Frank Michael O'Brien (1947). "The Story of the Sun : New York, 1833-1918". Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ The Story of the Sun. New York, 1833-1918, Chapter VIII "The Sun" During The Civil War

- ^ The Story of the Sun. New York, 1833-1918, Chapter VIII "The Sun" During The Civil War

- ^ Frank Michael O'Brien (1947). "The Story of the Sun : New York, 1833-1918". Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ The History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham, Mass, Volume 2, Benjamin Woodbridge Dwight, 1874, p.912

- ^ January 12, 1876, The Boston Globe from Boston, Massachusetts · 2, page 2

- ^ An Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of the United States, Treasurer's Accounts, 1873, p. 537

- ^ A World of Letters: Yale University Press, 1908-2008, Nicholas A. Basbanes, p. 6

- ^ Edmonds, Rick (February 12, 2023). "Can a magazine live forever? Scientific American, at 170, is giving it a shot". Poynter.

- ^ "About Scientific American". scientificamerican.com. February 12, 2023.

- ^ Jackson, Paul (2013). Jackson, Paul (ed.). "Executive Overview: Justice delayed is justice denied". Jane's All the World's Aircraft 2013. Washington, DC: Macdonald and Jane's: 8–10.

- ^ Archive of Stanley Yale Beach, aviation pioneer

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- "Moses Y. Beach". New York Times. July 21, 1868. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

Moses Yale Beach died suddenly Sunday morning at Wallingford, Conn,, where he was born, Jan. 7, 1800. In 1814 he was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker in Hartford, Conn., whom he served for four years, and then, purchasing his freedom, went into the cabinet business on his own account at Northampton, Mass.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

External links

[edit]- 19th-century American inventors

- People from Wallingford, Connecticut

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- Beach family

- 1800 births

- 1868 deaths

- 19th-century American diplomats

- Associated Press people

- 19th-century American journalists

- American male journalists

- Ambassadors of the United States to Mexico

- Yale family