Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel

Cross-section of the tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Status | Under construction |

| System | Turin–Lyon high-speed railway |

| Start | Maurienne, France |

| End | Susa Valley, Italy |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 2002 |

| Constructed | 2019–present |

| Traffic | passenger trains and freight trains |

| Character | Twin tube Passenger and freight |

| Technical | |

| Length | 57.5 km (35.7 mi) |

| No. of tracks | Double track |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrified | Electrified 25 kV 50 Hz AC |

| Operating speed |

|

| Highest elevation | 580 metres (1,900 ft) |

| Tunnel clearance | 8.4 metres (28 ft) |

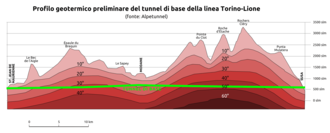

The Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel, also known as the Mont Cenis Base Tunnel,[1] is the largest engineering work of the Lyon–Turin rail link project. Once completed, it will facilitate the principal high-speed rail link between Italy and France, conveying both high-speed passenger trains and rail freight between the two countries. At 57.5 kilometres (35.7 mi), that tunnel will be the longest rail tunnel in the world, ahead of the 57.1 km (35.5 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel. It represents one third of the estimated overall cost of the project and is the only part of the line where work has started.

Crossing the Alps between the Susa Valley in Piedmont and Maurienne in Savoie.[2] It has an estimated cost of €8 billion.[3] During September 2016, a key agreement towards the tunnel's construction was reached by France and Italy. Three years later, competitive tenders to perform packaged elements of the construction work were sought. As of late-2022, the expected completion date for the base tunnel was 2032.[4]

History

[edit]During 2002, reconnaissance work commenced on the French side.[5] Initially, access points were excavated at Modane; excavations commenced in Saint-Martin-de-la-Porte during 2003, and at La Praz two years later.[6][failed verification] During 2011, excavations in support of the survey work started on the Italian side at La Maddalena.[7] Between 2016 and 2017, while full-rate construction of the tunnel had not officially commenced, a 9 km (5.6 mi) reconnaissance gallery had been tunneled from Saint Martin de la Porte towards Italy; it was bored along the intended axis of the South tube of the tunnel and was driven at its final diameter.[8] It will comprise the first eight percent of the tunnel's final length.[9]

During September 2016, it was announced that France and Italy had reached a mutual agreement for the construction of the tunnel.[3] Furthermore, the tunnel has been approved and part-financed by the European Union, which has stated its intention to finance 40% of the tunnel construction costs, and has indicated its willingness to increase its contribution to 55%, as well as to help fund its French accesses if those go beyond mere adaptations of the existing infrastructure.[10][11] In January 2017, a treaty was ratified between the two countries, confirming the project's approval.[12]

During March 2019, the Italian government issued a formal request for proposals (RFP) for the construction of the French portion of the base tunnel; in July 2019, a second RFP was released for the Italian portion of the tunnel.[13][14] During July 2020, it was announced that a consortium headed by the French civil engineering firm Vinci Construction Grands Projets had been awarded a contract for the construction of several major elements of tunnel, including four Avrieux shafts of up to 500 m (1,640 ft 5 in) depth, and the conventional excavation of multiple galleries and seven caverns at the foot of the Villarodin Bourget–Modane decline.[15]

All four of the access tunnels, three in France and one in Italy, have been completed and work began in early 2019 on the artificial tunnel that will be the entrance to the base tunnel on the French side.

In September 2019, the first of eight tunnel boring machines (TBMs) to be used on the project finished excavation of the first 9 km (5.6 mi) of the southern tube of the base tunnel, reaching the La Praz access adit. The 11.25 m (36 ft 11 in) diameter hard rock single shield TBM started its journey in the summer of 2016 from the Saint-Martin-de-la-Porte access adit and managed to maintain an average speed of 15–20 m (49 ft 3 in – 65 ft 7 in)/day. This first €390 million lot of the base tunnel was constructed by a joint venture of Batignolles TPCI, Eiffage TP, Ghella, CMC, Cogeis and Sotrabas. Egis and Alpina provided project management[16]

Contracts for the Mount Cenis Base Tunnel were awarded in July 2021:

- Lot 1 (€1.47 billion) for 22 km (13.7 mi) between Villarodin-Bourget/Modane and the Eastern (Italian) portal; expected to take 72 months

- Lot 2 (€1.43 billion) for 23 km (14.3 mi) between Saint-Martin-de-la-Porte/La Praz and Modane; expected to take 65 months

- Lot 3 (€228 million) for 3 km (1.9 mi) between Saint-Martin-de-la-Porte and the Western (French) Portal at Saint-Julien-Mont-Denis; the shortest, but with difficult geology requiring all blasting; expected to take 70 months

The approach routes are less advanced; planning is under way on the French side, but on the Italian side the proposed route has had fierce controversy, particularly in the Susa Valley the location of the Eastern portal, with a No TAV (no to high-speed rail) movement. The 2016 approval legislation could require extension of the tunnel by 5 km (3.1 mi) to reduce the impact on the local landscape.[17]

Characteristics

[edit]

The Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel is the principal engineering challenge of the in-development Turin–Lyon high-speed railway.[15] During 2019, it was stated that the tunnel's construction phase had been projected to take approximately ten years to complete.[18]

Opposition to the project is mostly organised under the loose banner of the No TAV movement.[19] As a result of protests against the original alignment of the tunnel in the Susa valley, it was decided to increase its length from 52 to 57.5 km (32.3 to 35.7 mi). Upon opening, the tunnel will be the longest rail tunnel in the world, followed by the Gotthard Base Tunnel (57.1 km (35.5 mi)), the Brenner Base Tunnel (55 km (34 mi), currently under construction), the Seikan Tunnel in Japan (53.85 km (33.46 mi)), the Channel Tunnel (50.45 km (31.35 mi)), and the Yulhyeon Tunnel in South Korea (50.3 km (31.3 mi)).

The tunnel portals will be in Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne on the French side and Susa on the Italian side. The geology adjacent to the French portal is heavily composed of fractured and sheared coal-bearing schists, as revealed by test drilling, which is poorly suited for using tunnel boring machines; thus, conventional drilling and blasting has to be used for the corresponding 5 km (3.1 mi) section.[20][21]

The cost of the joint Franco-Italian section (from Saint Jean de Maurienne to Val Susa) has been estimated at 8 billion euros (in January 2018 value).[3] This cost will be borne by the French and Italian governments, as well as drawing upon European Union (EU) funds.[22] The EU has agreed to provide 40% of the financing, but has indicated its willingness to increase its contribution to 55%, as well as to conditionally partially fund its French accesses.[10][11] However, a 2012 report by the French Court of Audit questioned the reliability of the estimated costs of the tunnel, as well the projected traffic volumes.[23]

The tunnel will be used by both freight trains and freight shuttles running at 100 km/h (62 mph), as well as by higher speed passenger trains operating at 220 km/h (140 mph); this design speed of slightly below the 250 km/h (160 mph) threshold used by the European Commission to define high-speed railways.[24] A stated aim of the project is a modal shift from road to rail for freight traffic over the Alps, as well as more passengers travelling by train rather than airliners, both of which achieve a reduction in CO2 emissions.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reina, Peter (16 June 2016). "After Earning World Record, Alpine Tunnels Move Ahead". Engineering News-Record. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "The Alpine tunnels". LTF. Archived from the original on 31 October 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "The European Commission welcomes the agreement between France and Italy to move ahead with the Lyon-Turin project". Mobility and Transport - European Commission. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "TELT Lyon Turin • A new excavation front for the Lyon-Turin".

- ^ "Close-up on works". LTF. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Boring contract". Railway Gazette International. 1 March 2005.

- ^ "Decouvrez la Maddalena" (in French). Lyon Turin Ferroviaire. 10 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Manuel Valls inaugure le tunnelier Federica au chantier du Lyon-Turin à Saint-Martin-La-Porte" (in French). LTF. Retrieved 1 August 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Telt annonce le percement de la section du tunnel de base entre Saint-Martin-la-Porte et La Praz" (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ a b "L'Union européenne confirme une participation accrue sur le Lyon-Turin" (in French).

- ^ a b "Lyon-Turin : vers les 55 % de contribution européenne" (in French).

- ^ "L'accord franco-italien pour la ligne ferroviaire Lyon-Turin définitivement adopté". Le Monde.fr (in French). 26 January 2017 – via Le Monde.

- ^ "Ligne ferroviaire Lyon-Turin : malgré les tensions, Rome valide le lancement des appels d'offres" (in French). Le Monde. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Lyon-Turin : les avis de marché publiés pour le tronçon italien" (in French). Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ a b c "Vinci consortium wins contract for preparatory work for Lyon–Turin rail line". worldconstructionnetwork.com. 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Lyon-Turin begins base line tender process". Tunneltalk. 19 March 2020.

- ^ Railway Gazette International, October 2021 (Volume 177 No 10), pp. 40–43

- ^ "Les travaux du Lyon-Turin débutent le 15 janvier". 18 December 2018.

- ^ Montalto Monella, Lillo (26 March 2019). "What is happening with the Lyon Turin high-speed line? Euronews traces the route to find out". Euronews. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Progressing the Lyon-Turin base rail link". www.tunneltalk.com.

- ^ "Covid-19 : retour à la normalité sur les chantiers du Lyon-Turin". TELT Lyon-Turin.

- ^ "Brenner base tunnel wins TEN-T funding". Railway Gazette International. 11 January 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012.

- ^ [1], "Situation et perspectives des finances publiques 2012 / Publications / Publications / Accueil - Cour des comptes". Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Decision No 661/2010/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 July 2010 on Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network".

External links

[edit] Media related to Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel at Wikimedia Commons- Lyon-Turin rail link official site (in Italian, French, and English)