Mononym

A mononym is a name composed of only one word. An individual who is known and addressed by a mononym is a mononymous person.

A mononym may be the person's only name, given to them at birth. This was routine in most ancient societies, and remains common in modern societies such as in Afghanistan,[1] Bhutan, Indonesia (especially by the Javanese), Myanmar, Mongolia, Tibet,[2] and South India.

In other cases, a person may select a single name from their polynym or adopt a mononym as a chosen name, pen name, stage name, or regnal name. A popular nickname may effectively become a mononym, in some cases adopted legally. For some historical figures, a mononym is the only name that is still known today.

Etymology

[edit]The word mononym comes from English mono- ("one", "single") and -onym ("name", "word"), ultimately from Greek mónos (μόνος, "single"), and ónoma (ὄνομα, "name").[a][b]

Antiquity

[edit]

The structure of persons' names has varied across time and geography. In some societies, individuals have been mononymous, receiving only a single name. Alulim, first king of Sumer, is one of the earliest names known; Narmer, an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, is another. In addition, Biblical names like Adam, Eve, Moses, or Abraham, were typically mononymous, as were names in the surrounding cultures of the Fertile Crescent.[4]

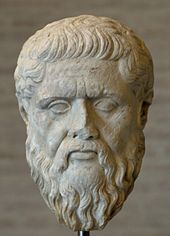

Ancient Greek names like Heracles, Homer, Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle, also follow the pattern, with epithets (similar to second names) only used subsequently by historians to distinguish between individuals with the same name, as in the case of Zeno the Stoic and Zeno of Elea; likewise, patronymics or other biographic details (such as city of origin, or another place name or occupation the individual was associated with) were used to specify whom one was talking about, but these details were not considered part of the name.[5]

A departure from this custom occurred, for example, among the Romans, who by the Republican period and throughout the Imperial period used multiple names: a male citizen's name comprised three parts (this was mostly typical of the upper class, while others would usually have only two names): praenomen (given name), nomen (clan name) and cognomen (family line within the clan) – the nomen and cognomen were almost always hereditary.[6]

Mononyms in other ancient cultures include Hannibal, the Celtic queen Boudica, and the Numidian king Jugurtha.

Medieval uses

[edit]Europe

[edit]During the early Middle Ages, mononymity slowly declined, with northern and eastern Europe keeping the tradition longer than the south. The Dutch Renaissance scholar and theologian Erasmus is a late example of mononymity; though sometimes referred to as "Desiderius Erasmus" or "Erasmus of Rotterdam", he was christened only as "Erasmus", after the martyr Erasmus of Formiae.[7]

Composers in the ars nova and ars subtilior styles of late medieval music were often known mononymously—potentially because their names were sobriquets—such as Borlet, Egardus, Egidius, Grimace, Solage, and Trebor.[8]

The Americas

[edit]

Naming practices of indigenous peoples of the Americas are highly variable, with one individual often bearing more than one name over a lifetime. In European and American histories, prominent Native Americans are usually mononymous, using a name that was frequently garbled and simplified in translation. For example, the Aztec emperor whose name was preserved in Nahuatl documents as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin was called "Montezuma" in subsequent histories. In current histories he is often named Moctezuma II, using the European custom of assigning regnal numbers to hereditary heads of state.

Post-medieval uses

[edit]France

[edit]

Some French authors have shown a preference for mononyms. In the 17th century, the dramatist and actor Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (1622–73) took the mononym stage name Molière.[9]

In the 18th century, François-Marie Arouet (1694–1778) adopted the mononym Voltaire, for both literary and personal use, in 1718 after his imprisonment in Paris' Bastille, to mark a break with his past. The new name combined several features. It was an anagram for a Latinized version (where "u" become "v", and "j" becomes "i") of his family surname, "Arouet, l[e] j[eune]" ("Arouet, the young"); it reversed the syllables of the name of the town his father came from, Airvault; and it has implications of speed and daring through similarity to French expressions such as voltige, volte-face and volatile. "Arouet" would not have served the purpose, given that name's associations with "roué" and with an expression that meant "for thrashing".[10]

The 19th-century French author Marie-Henri Beyle (1783–1842) used many pen names, most famously the mononym Stendhal, adapted from the name of the little Prussian town of Stendal, birthplace of the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whom Stendhal admired.[11]

Nadar[12] (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, 1820–1910) was an early French photographer.

In the 20th century, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873–1954, author of Gigi, 1945), used her actual surname as her mononym pen name, Colette.[13]

Elsewhere in Europe

[edit]In the 17th and 18th centuries, most Italian castrato singers used mononyms as stage names (e.g. Caffarelli, Farinelli). The German writer, mining engineer, and philosopher Georg Friedrich Philipp Freiherr von Hardenberg (1772–1801) became famous as Novalis.[14]

The 18th-century Italian painter Bernardo Bellotto, who is now ranked as an important and original painter in his own right, traded on the mononymous pseudonym of his uncle and teacher, Antonio Canal (Canaletto), in those countries—Poland and Germany—where his famous uncle was not active, calling himself likewise "Canaletto". Bellotto remains commonly known as "Canaletto" in those countries to this day.[15]

The 19th-century Dutch writer Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820–87), better known by his mononymous pen name Multatuli[16] (from the Latin multa tuli, "I have suffered [or borne] many things"), became famous for the satirical novel, Max Havelaar (1860), in which he denounced the abuses of colonialism in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

The 20th-century British author Hector Hugh Munro (1870–1916) became known by his pen name, Saki. In 20th-century Poland, the theater-of-the-absurd playwright, novelist, painter, photographer, and philosopher Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885–1939) after 1925 often used the mononymous pseudonym Witkacy, a conflation of his surname (Witkiewicz) and middle name (Ignacy).[17]

Royalty

[edit]

Monarchs and other royalty, for example Napoleon, have traditionally availed themselves of the privilege of using a mononym, modified when necessary by an ordinal or epithet (e.g., Queen Elizabeth II or Charles the Great). This is not always the case: King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden has two names. While many European royals have formally sported long chains of names, in practice they have tended to use only one or two and not to use surnames.[c]

In Japan, the emperor and his family have no surname, only a given name, such as Hirohito, which in practice in Japanese is rarely used: out of respect and as a measure of politeness, Japanese prefer to say "the Emperor" or "the Crown Prince".[19]

Roman Catholic popes have traditionally adopted a single, regnal name upon their election. John Paul I broke with this tradition – adopting a double name honoring his two predecessors[20] – and his successor John Paul II followed suit, but Benedict XVI reverted to the use of a single name.

Modern times

[edit]Surnames were introduced in Turkey only after World War I, by the country's first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as part of his Westernization and modernization programs.[21]

Some North American Indigenous people continue their nations' traditional naming practices, which may include the use of single names. In Canada, where government policy often included the imposition of Western-style names, one of the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was for all provinces and territories to waive fees to allow Indigenous people to legally assume traditional names, including mononyms.[22] In Ontario, for example, it is now legally possible to change to a single name or register one at birth, for members of Indigenous nations which have a tradition of single names.[23]

Asia

[edit]

In modern times, in countries that have long been part of the East Asian cultural sphere (Japan, the Koreas, Vietnam, and China), mononyms are rare. An exception pertains to the Emperor of Japan.

Mononyms are common in Indonesia, especially in Javanese names.[24]

Single names still also occur in Tibet.[2] Most Afghans also have no surname.[25]

In Bhutan, most people use either only one name or a combination of two personal names typically given by a Buddhist monk. There are no inherited family names; instead, Bhutanese differentiate themselves with nicknames or prefixes.[26]

In the Near East's Arab world, the Syrian poet Ali Ahmad Said Esber (born 1930) at age 17 adopted the mononym pseudonym, Adunis, sometimes also spelled "Adonis". A perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, he has been described as the greatest living poet of the Arab world.[27]

Other examples

[edit]In the West, mononymity, as well as its use by royals in conjunction with titles, has been primarily used or given to famous people such as prominent writers, artists, entertainers, musicians and athletes.[d]

The comedian and illusionist Teller, the silent half of the duo Penn & Teller, legally changed his original polynym, Raymond Joseph Teller, to the mononym "Teller" and possesses a United States passport issued in that single name.[29][30]

While some have chosen their own mononym, others have mononyms chosen for them by the public. Oprah Winfrey, American talk show host, is usually referred to by only her first name, Oprah. Elvis Presley, American singer, is usually referred to by only his first name, Elvis.

Western computer systems do not always support monynyms, most still requiring a given name and a surname. Some companies get around this by entering the mononym as both the given name and the surname.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Noun: "mononym"; adverb: "mononymously"; verb: "mononymize"; abstract noun: "mononymity".[3]

- ^ "Mononym" is defined in The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edition, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1989, volume IX, p. 1023) as "A term consisting of one word only […] Hence mononymic […] a[djective], consisting of a mononym or mononyms; mononymy […], a mononymic system; mononymize v[erb], to convert into a mononym; whence mononymization." The term is attested in the English language as early as 1872.

- ^ The names of a few European kings have included surname — for example, those of most of Poland's elected kings, such as Stefan Batory.[18]

- ^ A Paris Hilton lookalike, Chantelle Houghton, nicknamed "Paris Travelodge", became famous "for not being famous" after winning an extraordinary Celebrity Big Brother. Lucy Rock writes: "It is a select band. Madonna, Maradona, Pelé, Thalía, Sting...even, possibly, Jordan. People who wear their fame with such confidence that they have dispensed with the... concerns of having more than one name. They are the mononym brigade. Now there is one more.... Chantelle is... the apotheosis of that celebrity narrative that first gave us people who were famous for being good at something. Then came the people who were famous for simply... being famous. Now there is Chantelle, who is famous for not being famous at all."[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Goldstein, Joseph (2014-12-10). "For Afghans, Name and Birthdate Census Questions Are Not So Simple". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ a b MacArtney, Jane (August 26, 2008). "Tibets most famous woman blogger Woeser detained by police". The Times. London. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ See "mononym". A Word a Day. 2003-05-06. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ William Smith, Dictionary of the Bible, p. 2060.

- ^ William Smith, Dictionary of the Bible, p. 2060.

- ^ William Smith, Dictionary of the Bible, p. 2060.

- ^ Koen Goudriaan, "New Evidence on Erasmus' Youth", Erasmus Studies, vol. 39, no. 2 (6 September 2019), pp. 184–216.

- ^ Leach, Elizabeth Eva (2002). "Grimace, Magister Grimache, Grymace". In Finscher, Ludwig (ed.). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Vol. 8. Kassel, Germany: Bärenreiter. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-3-476-41020-7.

- ^ Maurice Valency, "Moliere", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 19, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Richard Holmes, Sidetracks, pp. 345–66; and "Voltaire's Grin", The New York Review of Books, November 30, 1955, pp. 49–55.

- ^ F.W.J. Hemmings, "Stendhal", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 25, p. 680.

- ^ Greg Jenner, Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen, Orion, 2020, ISBN 978-0-297-86981-8, p. 213.

- ^ Elaine Marks, "Colette", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 7, p. 230.

- ^ "Novalis", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 20, p. 503.

- ^ "Bellotto, Bernardo", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 3, p. 520.

- ^ Hugh Chisholm, "Dekker, Edward Douwes", Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, vol. 7, Cambridge University Press, 1911, p. 938.

- ^ "Witkiewicz, Stanisław Ignacy", Encyklopedia Polski, pp. 747–48.

- ^ "Stephen Báthory", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 3, p. 346.

- ^ Peter Wetzler, Hirohito and War: Imperial Tradition and Military Decision-Making in Prewar Japan, preface, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8248-1166-6.

- ^ Molinari, Gloria C. "The Conclave August 25th–26th, 1978". John Paul I The Smiling Pope. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Jan Siwmir, "Nieziemska ziemia" ("An Unearthly Land"), Gwiazda Polarna [The Pole Star]: America's oldest independent Polish-language newspaper, Stevens Point, Wisconsin, vol. 100, no 18, August 29, 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Vowel, Chelsea (4 November 2018). "Giving my children Cree names is a powerful act of reclamation". CBC News. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ "Newborn Registration Service". Service Ontario. Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ Robert C. Bone, "Suharto", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 25, p. 857.

- ^ National Public Radio report of 18 May 2009 about civilian Afghan victims of U.S. drone bombings in the U.S.-Taliban war. [1]

- ^ Hickok, John. Serving Library Users from Asia: a Comprehensive Handbook of Country-Specific Information and Outreach Resources. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019., p.588

- ^ "Adonis: a life in writing". The Guardian. 27 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

each autumn is credibly tipped for the Nobel in literature

- ^ Lucy Rock, "From Nobody Much to Someone Special", The Observer, January 29, 2006

- ^ della Cava, Marco R. (2007-11-16). "At home: Teller's magical Vegas retreat speaks volumes". USA Today. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ^ "Penn & Teller: Rogue Magician Is EXPOSING Our Secrets!!!". TMZ.com. 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hugh Chisholm, "Dekker, Edward Douwes", Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, vol. 7, Cambridge University Press, 1911.

- Encyclopedia Americana, Danville, CT, Grolier, 1986 ed., ISBN 0-7172-0117-1.

- Encyklopedia Polski (Encyclopedia of Poland), Kraków, Wydawnictwo Ryszard Kluszczyński, 1996, ISBN 83-86328-60-6.

- Richard Holmes, "Voltaire's Grin", New York Review of Books, November 30, 1995, pp. 49–55.

- Richard Holmes, Sidetracks: Explorations of a Romantic Biographer, New York, HarperCollins, 2000.

- Greg Jenner, Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen, Orion, 2020, ISBN 978-0-297-86981-8.

- William Smith (lexicographer), Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities..., 1860–65.

- Peter Wetzler, Hirohito and War: Imperial Tradition and Military Decision-Making in Prewar Japan, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8248-1166-6.

External links

[edit]- Peter Funt, "The Mononym Platform", The New York Times, February 21, 2007.

- Penn & Teller FAQ (Internet Archive).