Queen of Rhodesia

| Queen of Rhodesia | |

|---|---|

| |

Stamp issued 1966 | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| Formation | 11 November 1965 |

| Abolition | 2 March 1970 |

Queen of Rhodesia was the title asserted for Elizabeth II as Rhodesia's constitutional head of state following the country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom. However, the position only existed under the Rhodesian constitution of 1965 and remained unrecognised elsewhere in the world. The British government, along with the United Nations and almost all governments, regarded the declaration of independence as an illegal act and nowhere else was the existence of the British monarch having separate status in Rhodesia accepted. With Rhodesia becoming a republic in 1970, the status or existence of the office ceased to be contestable.

History

[edit]

Southern Rhodesia had been a crown colony with responsible government since 1923 and the transfer from rule under the British South Africa Company. The monarch of the United Kingdom was automatically recognised as monarch in the colonies. Following the UK refusing to grant Southern Rhodesia independence under minority rule, on 11 November 1965, they unilaterally declared independence and declared Elizabeth II as the queen of Rhodesia.[1] The independence declaration clarified that they were only breaking from the British government and affirmed loyalty to Elizabeth, viewing her as the separate Rhodesian monarch as part of a "loyal rebellion".[2] All Rhodesian oaths continued to be taken to her and the declaration of independence ended with "God Save The Queen".[3]

In response, the British Parliament passed the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965 which de jure affirmed British control of the colony and granted Queen Elizabeth II the power to act in the colony. She then issued an order in council to suspend the constitution and sacked the Rhodesian Front government.[4] These were ignored in Rhodesia and Prime Minister Ian Smith claimed it was the act of the British government and not of the Queen. The Rhodesian theory believed in the divisibility of the Crown to show their political autonomy.[5] The Rhodesians also ceased to recognise the governor of Southern Rhodesia, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, as the representative of the Queen and asked him to move out of Government House, Salisbury (which Gibbs refused to do). Smith then asked Queen Elizabeth II to appoint a governor-general of Rhodesia to act on her behalf, but she refused as she did not recognise the title and treated the request as if it had come from an ordinary citizen as Smith was no longer recognised as prime minister.[4] Elizabeth issued a response via Gibbs that said: "Her Majesty is not able to entertain purported advice of this kind and has therefore been pleased to direct that no action should be taken upon it".[4]

Accordingly Smith appointed Clifford Dupont as Officer Administering the Government in place of any royal appointment. It was initially suggested by Rhodesian officials that, due to his Stuart ancestry, they would appoint the Duke of Montrose as regent until Queen Elizabeth II recognised the title. The suggestion was rejected as a violation of the Regency Act 1953.[6] On the British side, the diplomat Michael Palliser suggested that Queen Elizabeth II appoint her husband Prince Philip as governor-general and have him arrive with a detachment of Coldstream Guards to legally sack Smith and the Rhodesian Front.[7] However the plan was not feasible due to bringing the royal family into politics and the risk that Philip would have been in.[7]

Power

[edit]The monarch's powers were the same as prior to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence. However they were de facto exercised by the Officer Administering the Government (Clifford Dupont) rather than by the governor of Southern Rhodesia (Sir Humphrey Gibbs) as Queen Elizabeth II's de jure representative. Every Rhodesian Bill presented to the Officer Administering the Government, had the following words of enactment:[8]

Be it enacted by His Excellency the Officer Administering the Government as representative of the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Parliament of Rhodesia

In 1968, she commuted the sentence of three African men sentenced to death.[9] Her pardon was ignored as the High Court of Rhodesia ruled that, as Rhodesian officials had not been consulted, the pardon came from the orders of the British government rather than from the Queen of Rhodesia, and the men were executed.[10][11][12]

Symbols

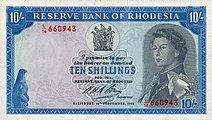

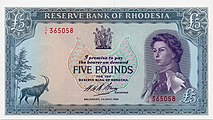

[edit]The Queen's portrait featured on Rhodesian banknotes and coins, as well as on postage stamps.[13]

- Queen Elizabeth II on Rhodesian banknotes

-

Ten shillings

-

One pound

-

Five pounds

Abolition

[edit]There had been calls for Rhodesia to become a republic as early as 1966.[14] The Whaley Commission had been set up by the Rhodesian government in 1967 to review the constitution and recommendations for alterations.[15] After Queen Elizabeth II's pardon was ignored, the Rhodesian government announced that the Queen's Official Birthday would no longer be a public holiday and they would only fire a 21-gun salute on her actual birthday.[16]

The Rhodesian Front published the Whaley Report's proposals for a referendum to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic with a new constitution a month after the executions.[15][17] Smith argued for it on the grounds that the British government "had denied us the Queen of Rhodesia".[18] In the 1969 Rhodesian constitutional referendum, the Rhodesian electorate voted in favour of the establishment of a republic. The move was opposed by the Roman Catholic Church over fears it would lead to further marginalisation of blacks in Rhodesia.[19] Gibbs also resigned as Governor at this time.[20] The internationally unrecognised republic was declared on 2 March 1970. In response, Queen Elizabeth II formally revoked the royal titles of the Royal Rhodesian Air Force and Royal Rhodesia Regiment.[21] Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother's honorary commissionership of the British South Africa Police was also suspended.[22] Dupont replaced Elizabeth II as head of state in Rhodesia as the new president.[23]

Contrary to Smith's hope that such a move would bring international legitimacy, it had the opposite effect. All countries that had relations with Rhodesia, except Portugal and South Africa, withdrew their diplomatic missions from the country. This was because originally they maintained relations because of the pre-existing royal accreditation but because a republic had been declared, that rationale was no longer valid.[24]

Rhodesia remained an unrecognised republic until Zimbabwe Rhodesia agreed to return to colonial status in 1979. Queen Elizabeth II resumed monarchical duties over the colony through her role as Queen of the United Kingdom and appointed Lord Soames as her representative as Governor of Southern Rhodesia until its independence as Zimbabwe on 18 April 1980.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ "As The Crown returns, watch out for these milestones". The Guardian. 18 August 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Kenrick, David (29 October 2018). "Settler Soul-Searching and Sovereign Independence: The Monarchy in Rhodesia, 1965–1970". Journal of Southern African Studies. 44 (6). Informa UK Limited: 1077–1093. doi:10.1080/03057070.2018.1516355. ISSN 0305-7070. S2CID 149475345.

- ^ Lowry, Donal (2020), Kumarasingham, H. (ed.), "The Queen of Rhodesia Versus the Queen of the United Kingdom: Conflicts of Allegiance in Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence", Viceregalism, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 203–230, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-46283-3_8, ISBN 978-3-030-46282-6, S2CID 226736902, retrieved 6 July 2021

- ^ a b c Twomey, Anne (2018). The Veiled Sceptre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1107056787.

- ^ Kenrick, David (2019). Decolonisation, Identity and Nation in Rhodesia, 1964–1979. Springer International Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-3030326982.

- ^ "Stuart Duke proposed as Regent of Rhodesia". The Guardian. 14 October 1965. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Lancaster House 1979: Part II, The Witnesses by FCDO Historians". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 20 December 2019. p. 118. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Issuu.

- ^ Rhodesia, Southern (1966), Act to Ratify and Confirm the Constitution of Rhodesia, p. 22

- ^ "Rhodesia (Royal Prerogative of Mercy) (Hansard, 4 March 1968)". Hansard. 4 March 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Retaliation threats made to Rhodesia". El Paso Times. 7 March 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ ""In hanging the three Africans, the Smith regime has been true to its basic nature."" (PDF). American Committee on Africa. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Rhodesia Defies Queen's Reprieve; Hanging Ordered for Three Africans Long Doomed". The New York Times. 6 March 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Marr, Andrew (2011), The Diamond Queen: Elizabeth II and Her People, Pan Macmillan, ISBN 9780230760943

- ^ "White Rhodesians salute Independence anniversary". Quebec Chronicle-Telegraph (Press release). 11 November 1966. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Harris, P. B. (1969). "The Failure of a 'Constitution': The Whaley Report, Rhodesia, 1968". International Affairs. 45 (2). Wiley, Royal Institute of International Affairs: 234–245. doi:10.2307/2613004. ISSN 1468-2346. JSTOR 2613004. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Queen". The Age. 20 April 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesia proposes to become a republic". The Vancouver Sun. 17 July 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesia ready to become a Republic". Red Deer Advocate. 18 July 1968. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Challenge By the Church in Rhodesia". The New York Times. 3 May 1970. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Kandiah, Michael (2001). "Rhodesia UDI" (PDF). Institute of Contemporary British History. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "That'll show them". Times Colonist. 16 March 1970. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Murphy, Phillip (2013). Monarchy and the End of Empire: The House of Windsor, the British Government, and the Postwar Commonwealth. Oxford University Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0199214235.

- ^ "Rhodesia becomes independent; seen as "just another dull occurrence"". Ames Daily Tribune. 2 March 1970. Retrieved 5 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Strack, Harry R. (1978). Sanctions: The Case of Rhodesia (1st ed.). Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-8156-2161-4.

- ^ "Rhodesia Restored To Colonial Status". The New York Times. 13 December 1979. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Elizabeth II

- National symbols of Rhodesia

- Politics of Rhodesia

- 1965 establishments in Rhodesia

- 1970 disestablishments in Rhodesia

- History of Rhodesia

- Former Commonwealth monarchies

- Former monarchies of Africa

- History of the British Empire

- History of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations