Mona Lisa replicas and reinterpretations

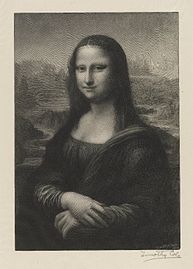

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is one of the most recognizable and famous works of art in the world, and also one of the most replicated and reinterpreted. Mona Lisa studio versions, copies or replicas were already being painted during Leonardo's lifetime by his own students and contemporaries. Some are claimed to be the work of Leonardo himself, and remain disputed by scholars. Prominent 20th-century artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dalí have also produced derivative works, manipulating Mona Lisa's image to suit their own aesthetic. Replicating Renaissance masterpieces continues to be a way for aspiring artists to perfect their painting techniques and prove their skills.[1]

Contemporary Mona Lisa replicas are often created in conjunction with events or exhibitions related to Leonardo da Vinci, for publicity. Her portrait, public domain and outside of copyright protection, has also been used to make political statements. Aside from countless print-reproductions of Leonardo's original Mona Lisa on postcards, coffee mugs and T-shirts, her likeness has also been re-imagined using coffee, toast, seaweed, Rubik's Cubes, and computer chips, to name only a few. Now over five-hundred years since her creation, the perpetuation of Mona Lisa's influence is reinforced with every reinterpretation.[2]

Background

[edit]At the beginning of the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned by Florentine nobleman Francesco del Giocondo to paint a portrait of his wife, Lisa.[3] The painting is believed to have been undertaken between 1503 and 1506.[4] Leonardo's portrait of Mona Lisa ("Mona" or "Monna" being the Italian honorific for "Madame") has been on display as part of the permanent collection at Paris' Louvre museum since 1797. It is also known as La Joconde in French and La Gioconda in Italian.[3][5]

Replicas of Mona Lisa date back to the 16th century,[4] including sculptures and etchings inspired by the painting.[6][7] But even by the early 20th century, historian Donald Sassoon has stated, Mona Lisa was still "just a well-respected painting by a famous old master" and was "not even the most valued painting in the Louvre."[2] The painting's theft on August 11, 1911, and the subsequent media frenzy surrounding the investigation and its recovery ignited public interest and led to the Mona Lisa gaining its current standing.[2]

Mona Lisa is in the public domain and not subject to copyright, whereas some modern works based on the original such as Marcel Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q. are protected by copyright law. [8]

Gioconda di Montecitorio

[edit]A 16th Century replica, named Gioconda di Montecitorio or Gioconda Torlonia hangs in the Chamber of Deputies (Italy), acquired from the collection of the Torlonia family. Following a restoration, some scholars assert that Leonardo made it as a replica of the original, while others dispute that conclusion.[9][10][11][12]

Isleworth Mona Lisa

[edit]A version of the Mona Lisa known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa and also known as the Earlier Mona Lisa was first bought by an English nobleman in 1778 and was rediscovered in 1913 by Hugh Blaker, an art connoisseur. The painting was presented to the media in 2012 by the Mona Lisa Foundation.[13]

The current scholarly consensus on attribution is unclear.[14] Some experts, including Frank Zöllner, Martin Kemp and Luke Syson denied the attribution;[15][16] professors such as Salvatore Lorusso, Andrea Natali,[17] and John F Asmus supported it;[18] others like Alessandro Vezzosi and Carlo Pedretti were uncertain.[19]

Prado Mona Lisa

[edit]In 2011, the Prado in Madrid, Spain, announced discovery of what may be the earliest known replica.[4][20] Miguel Falomir, heading the Department of Italian Renaissance Painting at the time of the discovery, stated the Prado "had no idea of (the painting's) significance" until a recent restoration.[4] Recovered from the Prado's vaults, the replica – which El Mundo newspaper dubbed "Mona Lisa's twin" (above, far right)[20] – was reportedly painted simultaneously alongside Leonardo as he painted his own Mona Lisa; in the same studio, by a "key" student.[4] It was painted on walnut. The replica has been part of the Prado's collection since the museum's founding in 1819.[21]

After restoration, the Prado's Mona Lisa revealed details covered by previous restorations and layers of varnish. Furnishings and fabrics were enhanced, as well as landscape and facial features. It is anticipated that such revelations may offer further insight into Leonardo's original. Experts at the Louvre reportedly supported the Prado museum's findings. The Prado replica was subsequently transported to the Louvre in 2012 to be displayed next to Mona Lisa as part of a temporary exhibition.[4][20][21]

Hermitage Mona Lisa

[edit]A version known as the Hermitage Mona Lisa is in the Hermitage Museum. It was made by an unknown 16th-century artist. The good workmanship, legibility and expressiveness emanating from the work were pointed out, the execution of portrait is presumably of Nordic Europe derivation, in particular German-Flemish. [22]

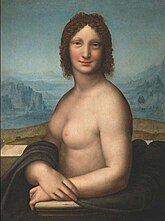

Mona Vanna

[edit]Two nude paintings bearing similarities to Leonardo da Vinci's original were part of a 2009 exhibition of artwork inspired by Mona Lisa. Displayed at the Museo Ideale in Leonardo's hometown of Vinci, near Florence, some believe one of the paintings – dating from Leonardo's time[6] – to be the work of Leonardo himself, and it has at times been credited to him.[23] Other experts theorize the painting, one of at least six known to exist, may be just another copy painted by "followers" of Leonardo. Scholarly dispute persists as to artist, subject and origin.[24] The nude in question, discovered behind a wall in a private library, reportedly belonged to an uncle of Napoleon Bonaparte, who owned another of Leonardo's paintings.[6] Facial features bear only vague resemblance, but landscape, compositional and technical details correspond to those of the Mona Lisa known worldwide today.[23][24]

A student and companion of Leonardo da Vinci known as Salaì painted one of the nude interpretations of Mona Lisa known, titled Mona Vanna. Salai's version is thought by some to have been "based on" the nude sometimes attributed to Leonardo, which is considered a lost work. Discussion among experts exists as to whether Salai, known to have modeled for Leonardo, may in fact have been the sitter represented in the original Mona Lisa.[25][26]

Another nude also known as Mona Vanna is generally attributed to Joos van Cleve, a Flemish artist active in the years following Mona Lisa's creation. Though the figure portrayed in van Cleve's painting bears no resemblance to Leonardo's Mona Lisa, the artist was known to mimic themes and techniques of Leonardo da Vinci. The artwork, dating to the mid-16th century, is in the collection of the National Gallery, Prague.[27]

20th century

[edit]

By the 20th century, Mona Lisa had already been a victim of satirical embellishment. Sapeck (Eugène Bataille), in 1883, depicted Mona Lisa smoking a pipe. Titled Le Rire (The Laugh), the artwork was displayed at the "Incoherents" exhibition in Paris at the time of its creation, making it among the earliest known instances of Mona Lisa's image being re-interpreted using contemporary irony. Further interpretations by avant-garde artists beginning in the early 20th century, coinciding with the artwork's theft, attest to Mona Lisa's popularity as an irresistible target. Dadaists and Surrealists were quick to modify, embellish and caricature Mona Lisa's visage.

L.H.O.O.Q.

[edit]Marcel Duchamp, among the most influential artists of his generation, in 1919 may have inadvertently set the standard for modern manifestations of Mona Lisa simply by adding a goatee to an existing postcard print of Leonardo's original. Duchamp pioneered the concept of readymades, which involves taking mundane objects not generally considered to be art and transforming them artistically, sometimes by simply renaming them and placing them in a gallery setting. In L.H.O.O.Q. the "found object" is a Mona Lisa postcard onto which Duchamp drew a goatee in pencil and appended the title.

The title, Duchamp is said to have admitted in his later years, is a pun. The letters L-H-O-O-Q pronounced in French form the sentence Elle a chaud au cul, colloquially translating into English as "She has a hot ass."[28] As was the case with many of his readymades, Duchamp made multiple versions of L.H.O.O.Q. in varying sizes and media throughout his career. An unmodified black and white reproduction of Mona Lisa on a playing-card, onto which Duchamp in 1965 inscribed LHOOQ rasée (LHOOQ Shaved), is among many second-generation variants referencing the original L.H.O.O.Q.[29]

Duchamp's parody of Mona Lisa was itself parodied by Francis Picabia in 1942, annotated Tableau Dada Par Marcel Duchamp ("Dadaist Scene for Marcel Duchamp"),[30] another example of second-generation interpretations of Mona Lisa. Salvador Dalí created his Self Portrait as Mona Lisa in 1954, referencing L.H.O.O.Q. in collaboration with Philippe Halsman, incorporating his photographs of a wild-eyed Dalí showing his handlebar moustache and a handful of coins.[2][30][31] In 1958, Icelandic painter Erró then incorporated Dalí's version into a composition which also included a film-still from Dalí's Un Chien Andalou. Fernand Léger and René Magritte are among the numbers of Modern art masters who've adapted Mona Lisa using their own iconography.[2] None of the parodies have tarnished Mona Lisa's image; rather, they reinforce her fame.[2] Duchamp's mustached Mona Lisa embellishment continues to inspire imitation. Contemporary conceptual artist Subodh Gupta gave L.H.O.O.Q. three-dimensional form in his 2009 bronze sculpture Et tu, Duchamp? Gupta, from India, considers himself an "idol thief" and has reinterpreted a number of iconic works from European art history.[32]

Post-tour years (1962–2000)

[edit]In December 1962, André Malraux, the first French minister of cultural affairs, lent the Mona Lisa to the United States at the request of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy.[33] The painting was displayed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. from January 9 to February 3, 1963.[34] Then it was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from February 7 to March 4, 1963.[34] Radio personality Bruce Morrow presided over a promotional event during Mona Lisa's exhibition in New York City. 70,000 entries of a "Best Mona" painting contest were exhibited at the Polo Grounds, with Salvador Dalí helping to pick the winner.[35]

During the painting's first American presentation in 1963, Fernando Botero—who had already painted Mona Lisa, Age Twelve in 1959—painted another Mona Lisa, this time in what would become his trademark "Boterismo" style of rendering figures disproportionately plump.[36] Andy Warhol created multiple renditions of Mona Lisa in his Pop art style.[37] Warhol's works Colored Mona Lisa (1963), Four Mona Lisas (1978), and Mona Lisa Four Times (1978) illustrate Warhol's method of silk-screening an image repetitively within the same work of art.[38]

In 1974 Salvatore Fiume made Gioconda Africana, a tribute to black female beauty: this "Gioconda" was donated to the Vatican and stays in Vatican Museums.[39] Mona Lisa is also referenced in artwork by Contemporary artists including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, adding to the veritable "who's who" list of artists putting their own spin on the portrait.[2] A paint by numbers version of Mona Lisa accompanied artist Suzanne Lacy during her 1977 travelogue Travels with Mona, documenting the painting process at landmark locations throughout Europe and Central America.[30]

From the 1980s through the end of the 20th Century, Mona Lisa continued to be the subject of re-interpretation among a new generation of emerging artists. Neo-expressionist artist Jean-Michel Basquiat created various depictions such as Crown Hotel (Mona Lisa Black Background) (1982), Mona Lisa (1983), and Lye (1983).[40] Pop artist Keith Haring juxtaposed Mona Lisa in a series of collages: Weeping Mona Lisa (1988), Apocalipse 7 (1988), and Malcolm X (1988).[41] Ballpoint art pioneer Lennie Mace created his Mona a'la Mace replica in 1993, a ballpoint "PENting" commissioned by Pilot pen company and featured on CBS News.[42][43] Artist Sophie Matisse, great-granddaughter of artist Henri Matisse, in her 1997 Monna Lisa (Be Back in Five Minutes) faithfully replicated the setting of the original painting, but omitted Mona Lisa from the scene; a concept she would repeat using other iconic artworks.[44]

21st century

[edit]British street artist Banksy in the first decade of the 21st century stenciled a "Mona Lisa Mujaheddin" holding a rocket launcher, and another mooning the viewer.

Mona Lisa was featured as the focus of Will.i.am's song and music video Mona Lisa Smile in Nicole Scherzinger was placed in the painting as Mona Lisa.[45][clarification needed]

Contemporary commercialization

[edit]Mona Lisa's iconic face has been available for years in all forms, appearing in advertisements for fashion and travel industries, and on the cover of magazines.[2] Leonardo da Vinci's own status as genius has been suggested as a factor contributing to the mystique of his creation.[46] The eyes of Leonardo's original Mona Lisa appear within cover-graphics for Dan Brown's 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code.[2] The Mona Lisa portrait also appeared in the teaser trailer for the 2006 film of the same name, although a replica was used for filming, appears only briefly in the film, and plays a very small part in the story. The sheer number and variety of replicas and reproductions since its creation in the early 16th century illustrates a so-called self-reinforcing dynamic; utilized in advertising because of its familiarity, its fame is reinforced thereby.[2]

Painting knock-offs of Mona Lisa and other Western masterpieces has become a cottage industry of sorts. Struggling artists in China paint them by the hundreds to supply the demand of American and European markets, and Mona Lisa is among the most popular requests. Working in cramped studios, or at home with children running around, these artists can earn a few hundred dollars (US) for a weeks worth of work on paintings which are then sold retail through mail-order catalogues.[1] Reproducing the works of old masters by hand not only provides a way to earn a living but also a way of furthering their art education by perfecting painting techniques.[1]

Among the most common motifs for satirization, Mona Lisa's face is embellished upon such as Duchamp adding a mustache. Replacing Mona Lisa's face or head altogether is another common motif; British artist Caroline Shotton in 2007 produced a series of paintings replicating classical works of art as cows, which she would go on to title her "Great Moo-sters" series. The inspiration for the series, she says, came to her while watching a documentary about Mona Lisa. Having settled upon the cow motif, she then formulated puns befitting her chosen subjects; whereby Mona Lisa became Moo-na Lisa.[47]

In the 2003 film Elf, Buddy uses an Etch-a-Sketch to draw the Mona Lisa in the process of building Santa Land by the North Pole in Gimbels. In Horton Hears A Who, the Mayor Ned McDodd shows his only son Jojo a family gallery where in one part his great grandmother is parodied as the Mona Lisa. And in My Little Pony: Equestria Girls – Friendship Games, there is a cake that Pinkie Pie and Fluttershy have baked with a picture of the Mona Lisa inside. In 2012, English actress Kathy Burke portrayed the Mona Lisa in the first series of Psychobitches.[48]

Unconventional interpretations

[edit]Mona Lisa replicas are sometimes directly or indirectly embellished as commentary of contemporary events. Exhibitions or events with ties to Leonardo da Vinci or Renaissance art also provide an opportunity for local artists to exploit Mona Lisa's image toward promoting the events.[46] The resulting artworks represent a broad spectrum of artists using creative license.

In a similar vein, artist Kristen Cumings in 2010 created her own "Jelly Bean Mona" replica using over 10,000 jelly beans. The one initial creation led to a full series of eight masterpiece replicas commissioned by a California jelly bean company as a publicity stunt and addition to the company's collection. Ohio's Center of Science and Industry (COSI) in Columbus thought the series noteworthy enough to be featured in an exhibition, held at the end of 2012.[49]

A replica of Mona Lisa publicized as the "world's smallest" was painted by Andrew Nichols of New Hampshire (USA) in 2011, intending "to break the record." Recreated at a 70:1 ratio, the miniature Mona Lisa measures approximately 1/4 by 7/16 inches (7 by 11 mm). Although his rendition drew media attention, it was never officially reported whether he had, in fact, broken any existing record.[citation needed] In 2013, a far smaller version of the painting, entitled the Mini Lisa, was created by a Georgia Institute of Technology student named Keith Carroll. The replica was created to demonstrate a new scientific technique called thermochemical nanolithography (TCNL). The Mini Lisa was just 30 micrometres (0.0012 in) wide, about 1/25,000th the size of the original.[50]

High school students attracted media attention in 2011 by recreating Mona Lisa on Daytona Beach, Florida (USA), using seaweed which had accumulated on shore. Claiming to have "too much time on their hands," it took two people approximately one hour to "turn the ugly seaweed into a work of art." Aside from photos appearing in the press, presumably their efforts were washed away with the tide.[51]

In 2012 the Portuguese designer Luís Silva created a poster for a campaign against violence on women representing Mona Lisa with a sore eye and a sombre expression, with the slogan "Could you live without her smile?"[52]

Mosaics

[edit]The computer age introduced digitally-produced or -inspired incarnations of Mona Lisa. Aside from versions constructed of actual computer motherboards,[53] mosaic-making techniques are another common motif used in such re-creations.[49]

Mimicking the heavy pixelation of a highly magnified computer file, Canadian artist Robert McKinnon assembled 315 Rubik's Cubes into a 36 by 48 inch Mona Lisa mosaic, an effect dubbed "Rubik's Cubism" by French artist Invader.[54] Similarly, colored Lego bricks have been employed to replicate Mona Lisa in a mosaic motif. A 2011 exhibition titled Da Vinci, The Genius at the Frazier Museum in Louisville, Kentucky attracted attention by having a Mona Lisa constructed by Lego artist Brian Korte.[46] Known as Brick Art, so-called "pro" Lego builders such as Eric Harshbarger have made multiple replicas of Mona Lisa. Matching the approximate 21 by 30 inch size (535 x 760+ mm) of Leonardo's original[5] requires upwards of 5,000 standard Lego bricks, but replicas measuring 6 by 8 feet have been built, requiring more than 30,000 bricks.[55][56][57]

Media coverage of the many incarnations of Mona Lisa often allude to the likely disbelief of Leonardo himself; of the intrigue she would come to inspire, and the unimaginable extremes of her re-portrayal.[53]

See also

[edit]- Cultural references to Leonardo da Vinci

- Mona Lisa (disambiguation)

- Salaì

- List of works by Leonardo da Vinci

References

[edit]- ^ a b c WuDunn, Sheryl (29 October 1989). "What Lies Behind The Strange Smile On the Mona Lisa". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Peter Hedstrom, Peter Bearman (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 336–337. ISBN 9780191615238. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ a b Robert, Evans (2013). "Fresh proof found for the 'original' Mona Lisa". news.MSN.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Earliest Mona Lisa copy claimed by Spanish museum". CBSNews.com. AP. February 3, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Hoobler, Dorothy & Thomas (May 2009). "Stealing Mona Lisa". excerpt of book. Vanity Fair. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Savage, Sam (June 13, 2009). "Nude Mona Lisa To Be Displayed At Exhibition In Italy". redOrbit.com. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^

Zollner, Frank (2000). Leonardo Da Vinci: 1452-1519. Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5979-7. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Copyrighting Right". How to avoid copyright violations in scientific presentations and on the Web. The NIH Catalyst. Sep–Oct 2008. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Roma: caso Gioconda di Montecitorio

- ^ Gioconda di Montecitorio

- ^ la Gioconda

- ^ la gemella della Gioconda

- ^ Dutta, Kunal (15 December 2014). "'Early Mona Lisa': Unveiling the one-in-a-million identical twin to Leonardo da Vinci painting". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Matthew (27 September 2012). "Second Mona Lisa Unveiled for First Time in 40 Years". ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Alastair Sooke. "The Isleworth Mona Lisa: A second Leonardo masterpiece?". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ "New proof said found for "original" Mona Lisa –". Reuters.com. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Lorusso, Salvatore; Natali, Andrea (January 2015). "Mona Lisa: A Comparative Evaluation of the Different Versions and Their Copies". Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage. 15: 80. doi:10.6092/issn.1973-9494/6168.

- ^ Asmus, John F. (1 July 1989). "Computer Studies of the Isleworth and Louvre Mona Lisas". Optical Engineering. 28 (7): 800–804. Bibcode:1989OptEn..28..800A. doi:10.1117/12.7977036. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (2018). Living with Leonardo: Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond. London, England: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500774236.

Alessandro Vezzosi, who spoke at the launch in Geneva, and Carlo Pedretti, the great Leonardo specialist, made encouraging but noncommittal statements about the picture being of high quality and worthy of further research.

- ^ a b c "Earliest Mona Lisa claimed by Spanish museum". CBS news. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on February 2, 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Mona Lisa Prado museum version on display". oldest Mona Lisa replica. Telegraph Media Group Ltd. February 21, 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Portrait of Gioconda (copy), hermitagemuseum.org.

- ^ a b staff writer, uncredited (2011). "Nude Mona Lisa-Like Painting Found". TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ a b staff writer, uncredited (June 15, 2009). "Mona Lisa' in the nude?". Work that resembles Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece on display. Daily News online. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Mona Lisa model was male". ABC news. February 3, 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Odd News". Da Vinci painted nude Mona Lisa. UPI. November 16, 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Half-length of a woman with bare breasts (Mona Vana Nuda)". artist bio database. National Gallery of Prague. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Seekamp, Kristina (2004). "Unmaking the Museum: Marcel Duchamp's Readymades in Context". Binghamton University Department of Art History. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ De Marting, Marco (2003). "Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache?". LHOOQ. Art Science Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2008-03-20. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Irish, Sharon (2010). Suzanne Lacy: Spaces Between. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 67, 68. ISBN 978-0-8166-6095-7. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Baron, Robert A. (1973). "Mona Lisa Images for a Modern World". exhibition catalogue. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Et tu, Duchamp?". installation. Mor Buro. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Wexelman, Alex (November 16, 2018). "When Jackie Kennedy Brought the Mona Lisa to America, Paris Rioted". Artsy. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ a b "Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ Boehlert, Eric (4 July 1992). "Top 40 (radio programming) Pioneer Rick Sklar Dies After Surgery". Billboard Magazine. Manhattan, New York, USA: 76. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Hanstein, Mariana (2003). Fernando Botero. Taschen. p. 93. ISBN 978-3-8228-2129-9.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (2003). Becoming Mona Lisa. Harvest Books via Amazon Search Inside. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-15-602711-3.

- ^ "Mona Lisa Takes New York | Christie's". www.christies.com. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ^ Musei Vaticani

- ^ Emmerling, Leonhard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960-1988. Taschen. p. 50. ISBN 978-3-8228-1637-0.

- ^ "Ideas Expressed in Image: Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the National Gallery of Victoria". COBO Social. 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ Liddell, C.B. (April 3, 2002). "The hair-raising art of Lennie Mace; Lennie Mace Museum". The Japan Times. Tokyo, Japan: Times Ltd. ISSN 0447-5763. OCLC 21225620. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ CBS Evening News; "Macedonia" exhibition preview, Lennie Mace interview; segment producer and interviewer Morry Alter; November 10, 1993

- ^ Wong, Sherry (January 2002). "Back in Five Minutes". Sophie Matisse exhibition preview. art net.com. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ "Mona Lisa Smile". YouTube. 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b c "Mona Lisa Replica Being Built in Louisville". Gray Television, Inc. Aug 25, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-09-19. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "The art cow-lection worth L3million". Mona Lisa as a Cow. Associated Newspapers Ltd. November 26, 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "Playhouse Presents: Psychobitches". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Masterpieces of Jelly Belly Art on Display at COSI". Jelly bean replica of Mona Lisa. Jelly Belly. July 24, 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-09-19. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Eoin O'Carroll (August 7, 2013). "'Mini Lisa': Georgia Tech researchers create world's tiniest da Vinci reproduction". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Graham, Chris (December 20, 2011). "High School students re-create famous painting on beach". Seaweed replica of Mona Lisa. Retrieved 7 March 2013.[dead link]

- ^ Francesca Bonazzoli, Michele Robecchi (2014). "'Mona Lisa to Marge: How the World's Greatest Artworks entered Popular Culture, Prestel, New York". Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Sood, Guarav (January 23, 2010). "Circuitry Mona Lisa sketch carved out from motherboards". Mona Lisa replica. Gizmowatch. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Mannino, Brynn (13 October 2009). "8 Rubik's Cube Artworks". Mona Lisa replica. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Forthofer, Jason (January 28, 2011). "MOC: LEGO Mona Lisa Mosaic". The Brick Show. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ "uncredited". MOCpages; Sean Kenney Design Inc. January 28, 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Harshbarger, Eric. "Freeze frame". MOCpages; Sean Kenney Design Inc. Retrieved 21 March 2013.