Missak Manouchian

Missak Manouchian | |

|---|---|

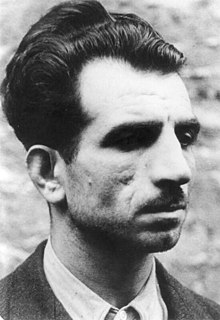

Manouchian in the 1930s | |

| Born | 1 September 1909 (registered 1906) |

| Died | 21 February 1944 (aged 34) |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Ivry Cemetery, Ivry-sur-Seine[1] |

| Other names | Michel Manouchian (francized)[2][3] |

| Occupation(s) | Trade unionist, poet,[4] translator, political activist |

| Organization | FTP-MOI |

| Political party | French Communist Party (from 1934)[5] |

| Movement | Labour movement, Anti-fascism, French Resistance |

| Spouse | Mélinée (née Assadourian) |

| Signature | |

Missak Manouchian (Armenian: Միսաք Մանուշեան; pronounced [misɑkʰ manuʃjɑn], 1 September 1909 – 21 February 1944) was a French-Armenian poet and communist activist. A survivor of the 1915–1916 Armenian genocide, he moved to France from an orphanage in Lebanon in 1925.[6] He was active in communist Armenian literary circles.[7] During World War II, he became the military commissioner of FTP-MOI, a group consisting of European immigrants, including many Jews,[8][9] in the Paris Region which carried out assassinations and bombings of Nazi targets.[8] According to one author, the Manouchian group was the most active one of the French Resistance.[10] Manouchian and many of his comrades were arrested in November 1943 and executed by the Nazis at Fort Mont-Valérien on 21 February 1944. He is considered a hero of the French Resistance and was entombed in the Panthéon in Paris.[11][12][13]

Early life

[edit]Manouchian is registered as being born on 1 September 1906 in Adıyaman, in Mamuret-ul-Aziz Vilayet, Ottoman Empire into an Armenian peasant family.[14][15] It was discovered in February 2024 that he was in fact born in 1909, when pages from his notebooks, discovered in May 2023 by his family at the Charents Museum of Literature and Arts, were obtained at the last minute for the exhibition celebrating his transfer to the Panthéon, and exhibited although not yet exploited by French researchers, as they were written in Armenian: his great-grandniece Hasmik Manouchian read in an entry dated February 1935 that he was 25. She said that this corroborated family stories that he had made himself older by three years, as he was not 18 when he arrived in France, but 15, too young to be allowed to work. The historian Denis Peschanski, who curated the exhibition, pointed out that this was relatively common for immigrants to France at the time. His tomb at the Panthéon, installed a short time before, is engraved with the date 1906.[16][17]

His parents were killed during the Armenian genocide of 1915, but he and his brother managed to survive.[4][14][18][19] In the early 1920s he settled in an Armenian General Benevolent Union-run orphanage in Jounieh, Lebanon, then a French protectorate.[15] He acquired education there and in 1925 moved to France.[15][6][14]

Eventually, Manouchian settled in Paris, where he took a job as a lathe operator at a Citroën plant.[15] During this period he was self-educated and often visited libraries[15] in the Latin Quarter.[6] He joined the General Confederation of Labour (Confédération Générale du Travail, CGT), a national association of trade unions which was the first of the five major French confederations. In the early 1930s, when the world-wide economic crisis of the Great Depression set in, Missak Manouchian lost his job. Disaffected with capitalism, he began earning a meager living by posing as a model for sculptors.[citation needed]

Political and literary career

[edit]In 1934, Manouchian joined the French Communist Party.[5] From 1935 to 1937 he edited the Armenian-language left-wing weekly newspaper Zangou, named after a river in Armenia.[6] The newspaper was anti-fascist, anti-Dashnak, anti-imperialist and pro-Soviet.[5][20]

Manouchian wrote poetry and, with an Armenian friend who used the pseudonym of Séma (Kégham Atmadjian), founded two communist-leaning[14] literary magazines, Tchank ("Effort") and Mechagouyt ("Culture").[20][21] They published articles on French literature and Armenian culture. The two young men translated the poetry of Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Rimbaud into Armenian, making many of these works available in Armenian for the first time. Both Manouchian and Séma enrolled at the Sorbonne to follow courses in literature, philosophy, economics, and history.[citation needed]

The following year, he was elected secretary of the Relief Committee for Armenia (HOC), an organization associated with the MOI (Immigrant Workforce Movement). At a meeting of the HOC in 1935, he met Mélinée Assadourian, who became his companion and, later, his wife.[citation needed]

World War II

[edit]

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939 Manouchian was arrested for his suspect communist ties, but was released in October and conscripted into the French 4th Specialist Training Company and dispatched to Brittany. After the defeat of June 1940, he returned to Paris to find that his militant activities had become illegal. (French authorities had banned the Communist Party as early as September 1939.) On 22 June 1941, when the invasion of the Soviet Union by the Nazis began, Manouchian was arrested by the occupying Germans in an anti-communist round-up in Paris. Interned in a prison camp at Compiègne, he was released after a few weeks without being charged, thanks to the efforts of his wife, Mélinée Assadourian.[22]

In early 1943 he was recruited by Boris Milev. Manouchian became the political chief of the Armenian section of the underground MOI, but little is known about his activities until 1943. In February of that year, Manouchian transferred to the FTP-MOI, a group of gunmen and saboteurs attached to the MOI in Paris.

Manouchian became the leader of the FTP-MOI in June/August[23] 1943, replacing Boris Holban.[24] Manouchian assumed command of three detachments, totaling about 50 fighters. The Manouchian group is credited with the assassination on 28 September 1943, of General Julius Ritter, the assistant in France to Fritz Sauckel, responsible for the mobilization and deportation of labor under the German STO (Obligatory Work Service) in Nazi-occupied Europe. (The attack was made by the partisans Marcel Rayman, Léo Kneller, and Celestino Alfonso.) The Manouchian group carried out almost thirty successful attacks on German interests from August to November 1943.[25] Charles Aznavour and his family were members of the Manouchian resistance group, and were recognized after the war for rescuing Jews and Armenians from Nazi persecution.[26]

Arrest and execution

[edit]On 16 November 1943,[27] the collaborationist French police forces arrested the Manouchian group[23] at Évry-Petit Bourg. His companion, Mélinée, managed to escape the police.[28]

Manouchian and the others were tortured to gain information, and eventually handed over to the Germans' Geheime Feldpolizei (GFP). The 23 were given a show trial for propaganda purposes before execution. Manouchian and 21 of his comrades were shot at Fort Mont-Valérien near Paris on 21 February 1944.[7][29][30] The remaining group member, Olga Bancic, was deported to Stuttgart and beheaded there in May 1944.[31]

In his last letter to his wife, Mélinée, Manouchian said that he forgave everyone except the one who betrayed us to save his skin and those who sold us.[8] "There was consensus that they were betrayed by one of their number, Joseph Davidovitch , who was arrested and tortured by the Nazis (before being released and shot by the Resistance). But some survivors also felt the French Communist Party had sacrificed the unit by refusing to smuggle vital Jewish combatants out of Paris after the French police began to tail them."[8]

Photographs of French Resistance agents facing a firing squad of Nazi officers were discovered in December 2009, and Serge Klarsfeld identified them as Manouchian and his group members.[32] The photographs began being permanently exhibited at Fort Mont-Valérien in June 2010.[33]

L'Affaire Manouchian

[edit]In June 1985, a television documentary by Mosco Boucault with the historian Stéphane Courtois working as a consultant entitled Des terroristes à la retraite (Terrorists in Retirement) was aired.[34] The documentary started an intense dispute over the identity of the informer who betrayed Manouchian and the rest of groupe Manouchian in 1943.[34] In the documentary, Mélinée Manouchian accused Boris Holban of being the informer.[34] In the 1986 book L'Affaire Manouchian by Philippe Robrieux, Holban was accused of being a member of an "ultra-secret special apparatus" within the PCF that took its orders from the Kremlin and that Holban had betrayed the groupe Manouchian on orders from Moscow.[34] The French journalist Alexandre Adler, in a series of articles in the Socialist newspaper Le Matin, defended Holban, arguing that he was not in Paris in the fall of 1943 and thus was not in a position to know the address of Manouchian or anyone else in his group.[35] Adler drew attention to a 1980 article in the Romanian journal Magazin istoric by the FTP-MOI intelligence chief Cristina Luca Boico, where she mentions that Holban was leading a maquis band in the Ardennes in November 1943 and had not been in Paris for some time.[36] L'Affaire Manouchian was finally settled in the 1990s when French police records were opened, revealing that Joseph Davidowicz, a resistance fighter who was arrested and then released by the Gestapo, was the informer who betrayed Manouchian.[37] Davidowicz was later killed by fellow resistance members, who accused him of spying for the Germans.[38]

Recognition

[edit]Following World War II, Armenians were perceived in France positively "solely in the reflective light of Missak Manouchian, who played an important role in the French anti-Nazi resistance."[40] Manouchian is a prominent figure in the bilateral relations between Armenia and France.[41]

In 2007, an exhibition dedicated to Manouchian was held at the Musée Jean Moulin in Paris in the scope of the Year of Armenia in France.[42][43] On 21 February 2014, on the 70th anniversary of the execution of Manouchian and his group, a commemoration ceremony was held at Fort Mont-Valérien. Notable attendees included French President François Hollande, Armenian foreign minister Eduard Nalbandyan and prominent French-Armenian singer Charles Aznavour.[44][45] On 13 March 2014, the Missak Manouchian Park was opened in central Yerevan, the Armenian capital, in attendance of Presidents Serzh Sargsyan and Hollande.[46][47]

On 5 March 1955, a street named for the Manouchian Group (fr) was dedicated in the 20th arrondissement of Paris.[48]

In 1978, a statue of Manouchian sculpted by Ara Harutyunyan was opened in the military cemetery of Ivry-sur-Seine, Paris.

A commemorative plaque was installed on 22 February 2009 at 11 rue de Plaisance, in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. The old hotel at this address was the last home shared by Manouchian and his wife, Mélinée.[49][50]

In February 2010, busts of Manouchian were inaugurated in Marseille, in a square named after him, and in Issy-les-Moulineaux.[51] In June 2014, the memorial in Marseille was defaced with a swastika.[52] Two far-right activists, who admitted their participation, were sentenced to 100 hours of community service in January 2015.[53]

Due to his communist ideology, Manouchian was immediately recognized as a hero in the Soviet Union. Soviet Armenian author Marietta Shaginyan described him as an "example of an Armenian who preserved his nationality, and at the same time became a class-conscious worker and a militant communist in his adopted country."[54] Russian poet Sergei Shervinsky hailed him in a 1956 Ogoniok article as a "Fighter, Worker, Poet".[55] A school in Yerevan, Armenia—founded in 1947—was named for Manouchian in 1963.[56]

Pantheonization

[edit]In January 2022 a campaign was launched by Nicolas Daragon, mayor of Valence, Drôme, and Jean-Pierre Sakoun, president of Comité Laïcité République, and others to move Manouchian's ashes to the Panthéon. Supporters included Katia Guiragossian, a great-niece of Missak and Mélinée Manouchian, sociologist Nathalie Heinich, historian Denis Peschanski, and others.[57] It further gained the support of the mayors of Paris and Marseille Anne Hidalgo and Benoît Payan,[58][59][60][61] former French ambassador to Armenia Jonathan Lacôte,[62] and MPs from various parties.[63] In March 2022 Europe 1 reported that French President Emmanuel Macron was planning pantheonization of Manouchian. A close presidential adviser was quoted as saying: "This file is at the top of the pile."[64] Le Monde reported Macron met with supporters of the campaign on March 30, 2022 at the Élysée Palace and several days later, Macron said of Manouchian: "I think he is a very great figure and that makes a lot of sense."

Missak Manouchian and his wife Mélinée were entombed in the Panthéon on 21 February 2024, in commemoration of his execution's 80th anniversary.[65][66] He became the first foreign Resistance fighter and first communist to enter the Panthéon.[67][68]

In popular culture

[edit]- In 1955, Louis Aragon wrote a poem, "Strophes pour se souvenir", loosely inspired by the last letter that Manouchian wrote to his wife Mélinée.[69] In 1959 Léo Ferré set the poem to music and recorded it under the title "L'Affiche rouge".

- In the 2009 novel Missak by Didier Daeninckx, set in 1955, a journalist investigates who betrayed Manouchian and discovers the informer was Boris Bruhman, a thinly disguised version of Boris Holban.[70]

- Films

- The 1985 film Terrorists in Retirement (Des terroristes à la retraite) offers speculations on why "beginning in 1943, the [French] Communist Party began deliberately dispatching the partisans [including the Manouchian group] on missions that their Communist leaders knew would lead to their arrest and probable execution."[71]

- The 2009 film The Army of Crime (L'Armée du crime), directed by Robert Guédiguian, is dedicated to Manouchian and his group.[9][72][73] In the film, Manouchian appears as the hero, and many parallels are drawn between the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust as the film emphasizes Manouchian's opposition to genocide in the Second World War because he was a survivor of genocide in the First World War.[74] In a review of L'Armée du crime in Le Monde on 15 November 2009, the French historian Stéphane Courtois complained that the film wrongly portrayed Manouchian as an "anti-Stalinist" communist and the film was unrealistic in that it had Manouchian casually and routinely violating the rules of clandestine activity.[74] The British historian Gawin Bowd described the film as part of a tendency to move away from the traditional gallocentric view of résistancialiste where resistance in France was entirely the work of the French.[74] However, Bowd noted that the way in which L'Armée du crime portrays Manouchian as a martyr who mort pour la France (died for France) does suggest that Manouchian was more of a French hero than an Armenian one as the "ultimate horizon of Frenchness remains".[74]

- Missak Manouchian, une esquisse de portrait (2012) is a documentary directed by Michel Ionascu.[75]

See also

[edit]- Affiche Rouge (Red Poster)

References

[edit]- ^ "Tombe Missak et Mélinée Manouchian". acam-france.org (in French). Association Culturelle Arménienne de Marne-la-Vallée.

- ^ Walter, Gérard [in French] (1960). Paris Under the Occupation. Orion Press. p. 209.

- ^ Maury, Pierre (2006). La résistance communiste en France, 1940–1945: mémorial aux martyrs communistes (in French). Temps des cerises. p. 240.

- ^ a b Graham, Helen (2012). The War and Its Shadow: Spain's Civil War in Europe's Long Twentieth Century. Apollo Books. p. 84.

- ^ a b c Khaleyan 1946, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Mouradian, Claire (2010). Les Arméniens en France: du chaos à la reconnaissance (in French). Editions De L'attribut. p. 48. ISBN 978-2916002187.

- ^ a b Ter Minassian, Anahide [in French]; Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (1997). Histoires croisées: diaspora, Arménie, Transcaucasie, 1880–1990 (in French). Editions Parenthèses. p. 40. ISBN 9782863640760.

- ^ a b c d Riding, Alan (9 January 2001). "French Film Bears Witness To Wartime Complicity". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Rancière, Jacques (2012). The Intellectual and His People: Staging the People, Volume 2. Verso Books. p. 43.

- ^ Argyle, Ray (2014). The Paris Game: Charles de Gaulle, the Liberation of Paris, and the Gamble that Won France. Dundurn. p. 434. ISBN 9781459722873.

- ^ "Hommage au résistant Missak Manouchian". Le Parisien (in French). 15 November 2014.

...au héros de la résistance et militant communiste Missak Manouchian...

- ^ de Chabalier, Blaise (16 September 2009). "Stéphane Courtois : "Manouchian fut une erreur de casting"". Le Figaro (in French).

Morts en héros, Missak Manouchian...

- ^ "EN DIRECT - Missak Manouchian et ses frères d'armes étrangers sont entrés au Panthéon". Le Figaro (in French). 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Atamian, Astrig (2007). "Les Arméniens communistes en France, une histoire oubliée". Amnis. Revue de civilisation contemporaine Europes/Amériques (in French) (7). University of Western Brittany. doi:10.4000/amnis.853. ISSN 1764-7193.

- ^ a b c d e Khaleyan 1946, p. 71.

- ^ Chemin, Ariane (6 March 2024). "Missak Manouchian n'est pas mort à 37 ans, mais à 34 : le résistant s'était vieilli de trois ans à son arrivée en France". Le Monde (in French). Paris. ISSN 0395-2037.

- ^ Durieux, Jeanne (8 March 2024). "Erreur sur la stèle de Missak Manouchian au Panthéon : le résistant n'est pas né en 1906 mais en 1909". Le Figaro (in French). Paris. ISSN 0182-5852.

- ^ Houssin, Monique (2004). Résistantes et résistants en Seine-Saint-Denis: un nom, une rue, une histoire (in French). Editions de l'Atelier. p. 252. ISBN 9782708237308.

- ^ "Missak Manouchian (le Chef)". L'affiche Rouge. 14 April 2010.

- ^ a b Taturyan, Sh. (1981). "Մանուշյան Միսաք [Manushyan Misak]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 7. pp. 255–6.

- ^ Atamian, Christopher (29 August 2011). "What's Happened to Our Culture in the Diaspora?". Ararat Magazine. Armenian General Benevolent Union. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Missak Manouchian – Ein armenischer Partisan Archived 27 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Poznanski, Renée (2001). Jews in France During World War II. University Press of New England. p. 352. ISBN 0-87451-896-2.

- ^ Cobb, Matthew (2009). The Resistance: The French Fight Against the Nazis. Simon & Schuster. p. 187. ISBN 978-1847391568.

- ^ Harrison, Donald H. (11 January 2011). "San Diego Jewish Film Festival preview: 'Army of Crime'".

- ^ "Il y a 69 ans, Missak Manouchian était arrêté". Nor Haratch (in French). 16 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- ^ "(in Russian) Армянский боец французского Сопротивления". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Courtois, Stéphane (2 July 2004). "Portrait de Boris Holban" (PDF). Le Monde (in French).

la BS2 arrête Manouchian et plus de soixante de ses camarades, dont les 23 figurant sur la fameuse "Affiche rouge", qui seront fusillés au mont Valérien, le 21 février 1943.

- ^ Dutent, Nicolas (20 February 2015). "Missak Manouchian : Cet idéal qui le faisait combattre". L'Humanité (in French).

- ^ {{cite web [title=GOLDA (OLGA) BANCIC |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/id-card/golda-olga-bancic |website=Holocaust Encyclopedia |publisher=US Holocaust Memorial Museum |access-date=21 January 2022}}

- ^ Hugues, Bastien (11 December 2009). "Les derniers instants du groupe Manouchian". Le Figaro (in French).

- ^ Samuel, Henry (20 June 2010). "First pictures of French Resistance killed by Nazi firing squad". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Bowd 2014, p. 550.

- ^ Bowd 2014, p. 552.

- ^ Bowd 2014, p. 553.

- ^ Bowd 2014, p. 554.

- ^ Dobbs, Michael (6 July 1985). "TV Show on French Resistance Stirs Controversy". WashingtonPost.com. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "New postage stamp dedicated to Missak Manouchian". HayPost. 26 May 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021.

- ^ Al-Rustom, Hakem (2013). "Diaspora Activism and the Politics of Locality: The Armenians in France". In Quayson, Ato; Daswani, Girish (eds.). A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 476. ISBN 9781405188265.

- ^ Tardivier, Nelly (July–August 2007). "Arménie, mon amie est dédiée à une culture forte" (PDF). culture.gouv.fr (in French). French Ministry of Culture. p. 5.

Les 500 000 Français d'origine arménienne représentent un ciment extraordinaire entre les deux pays, avec de hautes figures commecelles de Missak Manouchian.

- ^ "Autour de "Missak Manouchian, les Arméniens dans la Résistance en France"". Nouvelles d'Arménie Magazine (in French). 26 February 2007. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Missak Manouchian, les Arméniens dans la Résistance en France" (in French). Fondation de la Résistance.

- ^ "President Hollande Attends Missak Manouchian Commemoration". Asbarez. 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Foreign Minister Edward Nalbandian participated in the commemoration ceremony dedicated to the French Resistance and the group of Missak Manouchian". mfa.am. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Armenia. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Gevorgyan, Alisa (13 May 2014). "Missak Manouchian Park opens in Yerevan". Public Radio of Armenia.

- ^ "Hollande, Sargsyan Attend Manouchian Park Opening". Hetq Online. 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Rue du Groupe Manouchian 75020 Paris". acam-france.org (in French). Association Culturelle Arménienne de Marne-la-Vallée.

- ^ "Dévoilement de la plaque Missak Manouchian". mairie14.paris.fr (in French). Mairie du 14e. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Memorial plaque unveiled in Paris in honor of French Resistance hero Misak Manushyan". PanARMENIAN.Net. 23 February 2009.

- ^ "Buste Missak Manouchian Place Groupe Manouchian – 92130 Issy-les-Moulineaux". acam-france.org (in French). Association Culturelle Arménienne de Marne-la-Vallée.

- ^ "Statue of Missak Manouchian in Marseille desecreted". Public Radio of Armenia. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "Profanation de la stèle Manouchian : deux militants d'extrême droite condamnés". Le Monde.fr (in French). 9 January 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Shaginyan, Marietta (1954). Journey Through Soviet Armenia [По Советской Армении]. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 45.

- ^ Shervinsky, Sergei [in Russian] (3 June 1956). "Борец, Рабочий, Поэт... [Fighter, Worker, Poet...]". Ogoniok (in Russian). Moscow: 16.

- ^ "The schools subordinated to the municipality of Yerevan". yerevan.am. Yerevan Municipality.

- ^ "Après Joséphine Baker, Missak Manouchian a sa place au Panthéon [After Josephine Baker, Missak Manouchian has his place in the Pantheon]". Libération (in French). 13 January 2022. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022.

- ^ Gallagher, Tim (25 April 2022). "Calls for Armenian resistance fighter to enter French Pantheon". Euronews (via AFP). Archived from the original on 16 May 2022.

- ^ Gréco, Bertrand (18 February 2023). "Anne Hidalgo réclame la panthéonisation du résistant Missak Manouchian [Anne Hidalgo calls for the pantheonization of the resistant Missak Manouchian]". Le Journal du Dimanche. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023.

- ^ Hidalgo, Anne. "Faire entrer Missak Manouchian au Panthéon : en voilà un beau et nécessaire projet pour la France ! [Bringing Missak Manouchian into the Pantheon: here is a beautiful and necessary project for France!]". Twitter (in French). Archived from the original on 22 February 2023.

- ^ Payan, Benoît (20 February 2023). "Missak Manouchian, était un héros de la résistance". Twitter (in French). Archived from the original on 22 February 2023.

Nous sommes nombreux à le demander : la France serait grande de le faire entrer au Panthéon.

- ^ Lacôte, Jonathan (7 December 2021). "Petit fil pour une entrée de Missak Manouchian au Panthéon [Little thread for Missak Manouchian's entry to the Pantheon]" (in French). Archived from the original on 22 February 2023.

- ^ examples: Anne-Laurence Petel [1]; Aurélien Saintoul [2]; Stéphane Troussel [3]; Martine Etienne [4]; Pierre Ouzoulias [5], [6]

- ^ Serais, Jacques (23 March 2022). "Emmanuel Macron pense à panthéoniser Missak Manouchian [Emmanuel Macron thinks of pantheonizing Missak Manouchian]" (in French). Europe 1. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022.

- ^ "En direct: au Panthéon, Emmanuel Macron salue la mémoire de Missak Manouchian, Français de préférence, Français d'espérance". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "France inducts Resistance hero Manouchian into Panthéon". France 24. 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Missak Manouchian, héros de la Résistance d'origine arménienne, va faire son entrée au Panthéon". Le Monde.fr (in French). 18 June 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "France honors foreign Resistance fighters as WWII hero Manouchian is inducted into the Panthéon". AP News. 21 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "The Red Poster, by Louis Aragon".

- ^ Bowd 2014, p. 555-556.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (10 January 2001). "FILM REVIEW; Sorrow and Perfidy: Unsung Resistance Fighters". The New York Times.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (19 August 2010). "The Army of Crime (2009)". The New York Times.

- ^ Kempner, Aviva (18 August 2010). "Vive La Resistance, Encore!". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- ^ a b c d Bowd 2014, p. 555.

- ^ Mihai. "MISSAK MANOUCHIAN, une esquisse de portrait". arte.tv (in French). Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bowd, Gavin (December 2014). "Romanians of the French Resistance". French History. 28 (4): 541–559. doi:10.1093/fh/cru080. hdl:10023/9636.

- Khaleyan, Ervand (1946). "Նյութեր Միսակ Մանուշյանի մասին [Materials on Missak Manouchian]". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR: Social Sciences (in Armenian) (4): 71–86. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- Further reading

- Manouchian, Mélinée (1954). Manouchian (in French). Paris: Les Éditeurs français réunis.

- Poghossian, Varouzhan (1985). "Միսաք Մանուշյանի նամակները [Misak Manushian's letters]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (7): 90–92.

- Daeninckx, Didier (2009). Missak: l'enfant de l'Affiche rouge (in French). Perrin. ISBN 978-2262028022.

- Benson, Darcy Colleen (2014). "Communist, Foreigner, Résistant?: Post-War Commemoration of Missak Manouchian and Marcel Langer" (Honors Thesis). Student Honors Theses by Year. Dickinson College.

- Robrieux, Philippe [in French] (1986). L'Affaire Manouchian (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2213017875.

- 1909 births

- 1944 deaths

- Armenian communists

- Armenian male poets

- Executed activists

- FTP-MOI

- French people of Armenian descent

- Communist members of the French Resistance

- Members of the General Confederation of Labour (France)

- People from Adıyaman

- Armenian people of World War II

- Resistance members killed by Nazi Germany

- Syrian emigrants to France

- Armenian genocide survivors

- Armenian people executed by Nazi Germany

- French people executed by Nazi Germany

- 20th-century Armenian poets

- Affiche Rouge

- Burials at Ivry Cemetery

- Communists executed by Nazi Germany

- People executed by Nazi Germany by firing squad

- Deaths by firearm in France

- People executed by Nazi Germany occupation forces