Ukrainian Dorian scale

In music, the Ukrainian Dorian scale (or the Dorian ♯4 scale) is a modified minor scale with raised 4th and 6th, and lowered 7th degrees, often with a variable 4th degree. It has traditionally been common in the music of Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, and the Mediterranean including Jewish, Greek, Ukrainian, and Romanian music. Because of its widespread use, this scale has been known by a variety of names including Altered Dorian, Hutsul mode and Mi Shebeirach. It is also closely related to the Nikriz pentachord found in Turkish or Arabic maqam systems.

It is one of the two harmonic Dorian scales, the other is the Dorian ♭5 scale.

| scale | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| original Dorian scale | minor triad | minor triad | major triad | major triad | minor triad | diminished triad | major triad |

| Dorian ♯4 scale | minor triad | major triad | major triad | diminished triad | major triad | diminished triad | augmented triad |

| Dorian ♭5 scale | diminished triad | minor triad | minor triad | major triad | augmented triad | diminished triad | major triad |

| scale | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| original Dorian scale | minor seventh chord | minor seventh chord | major seventh chord | dominant seventh chord | minor seventh chord | half-diminished seventh chord | major seventh chord |

| Dorian ♯4 scale | minor seventh chord | dominant seventh chord | major seventh chord | diminished seventh chord | minor major seventh chord | half-diminished seventh chord | augmented major seventh chord |

| Dorian ♭5 scale | half-diminished seventh chord | minor seventh chord | minor major seventh chord | dominant seventh chord | augmented major seventh chord | diminished seventh chord | major seventh chord |

Terminology

[edit]Although this scale has been used in the music of Southeastern Europe and Western Asia for centuries, our terms for it only date to the twentieth century.[1] The term Ukrainian Dorian (German: Ukrainisch-dorisch) was coined by the pioneering Jewish musicologist Abraham Zevi Idelsohn in the 1910s, who was influenced by the Ukrainian folklorist Filaret Kolessa and associated this scale with Ukrainian music (particularly in the epic poems called "Dumy").[2][3] Because of this association it has also been called the "Duma mode" in the context of Ukrainian music. At other times Idelsohn called it simply a dorian mode with an augmented fourth.[4] Moisei Beregovsky, a Soviet ethnomusicologist, was critical of Idelsohn's work and preferred the term "altered Dorian" (Russian: Измененный дорийский); he agreed it was most common in Ukrainian Dumy and also in Romanian, Moldavian and Jewish music.[5][6] Mark Slobin, an American ethnomusicologist, who translated Beregovski's work to English, calls it the "raised-fourth scale".[2][5][7]

In folk and religious music from various ethnic groups of Southeastern Europe it has a variety of other names. In the context of Jewish cantorial music or Nusach it has been named after various prayers it was used in; most commonly "Mi Shebeirach scale", but also Av HaRachamim and others.[4] Since the 1980s some of these religious terms have been applied to Klezmer music as well, most commonly Mi Shebeirach. In Russian, it is called the Hutsul mode (Russian: гуцульський лад) after the ethnic group of that name. In the context of modern Greek music it has variously been called Karagouna, Romanikos, Nikriz or Piraeotiko minore (Piraeus minor)[7][4] In contexts influenced by the Turkish makam system, which includes Greek music, it is often compared to the pentachord Nikriz.[8]

Characteristics

[edit]

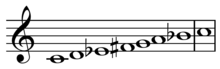

The Ukrainian Dorian scale is sometimes described as a Dorian mode with a raised fourth degree. It shares the same intervals as the Harmonic minor scale and the Phrygian dominant scale. It can be seen, as Idelsohn originally described it in the 1910s, as a seven-note scale.[3] For example, a C scale in Ukrainian Dorian would consist of C, D, E♭, F♯, G, A, B♭.

However, there are other aspects to its modal usage in traditional music. Its lower range consists of the pentachord Nikriz; in C, the notes would be C, D, E♭, F♯, G. Its upper range normally consists of the tetrachord G, A, B♭, C. Below the tonic, however, would typically be the tetrachord G, A, B♮, C. In many cases, at some point in the melody the fourth degree is flattened to F♮, with a possibility to flatten the sixth and seventh degrees to A♭ and B♭ (natural minor).[7][6] So, in traditional modal uses it often extends beyond one octave and has variation in its intervals.[2][9]

The main tonal basis of this scale is a minor triad.[6] However, the raised fourth is more difficult to harmonize, and therefore pieces written in this scale are often accompanied by a drone in traditional music, or with diminished chords.[7]

Use in music

[edit]Traditional and ethnic music

[edit]This mode is especially common in areas of Eastern and Southeastern Europe and the Mediterranean which were under the rule or influence of the Ottoman Empire, and before it the Byzantine Empire.[7][10] There has not yet been a thorough study of its use across various cultures.[9] In a 1980 study, Slobin noted it is particularly prevalent in Ukraine, Romania and Moldova, appears sometimes in the music of Maramureș, Bulgaria, Greece, and Slovakia; that it is rare in the folk music of Russia, Belarus and Hungary but appears fairly commonly in Jewish music from those areas.[2][11] The historical ethnomusicologist Walter Zev Feldman describes it as being present in an area from Western Anatolia to Ukraine.[9] Manuel notes that Jewish and Roma musicians may have been important in spreading or maintaining it across cultural zones and imperial borders.[7] Scholars generally agree that its origin is unknown.[6][2] Certain usages of this scale are common across many of these cultural groups, such as modulations between it and the Phrygian dominant scale.[7]

Ukrainian music

[edit]As stated above, the common English name for this scale (Ukrainian Dorian) came about because early folklorists and musicologists associated it with the Dumy epic ballads of Ukraine. These ballads, which date back to the fifteenth century and were historically performed by Kobzars, were typically composed using this scale.[12] Aside from Dumy ballads, this scale is particularly associated with the music of the Hutsuls, an ethnic group of the Carpathian Mountains, to the degree that it is often called the Hutsul mode (Ukrainian: Гуцульський лад).[13][14]

Ashkenazic Jewish music

[edit]This scale is often associated in an English-language context with Ashkenazic Jewish music, and pieces in Ukrainian Dorian and the Phrygian dominant scale (known colloquially as Freygish) are generally said to have a "Jewish" feel which sets them apart from other music.[2] It appears in a number of genres, including religious music, folk songs, Klezmer, and composed Yiddish songs of the early 20th century.[15] Beregovsky, the Soviet researcher of Jewish music working in the 1930s, estimated that this mode was used in 4 or 5 percent of Jewish folk songs and slightly more than 10 percent of instrumental tunes.[2][6]

Its use is common in Yiddish theatre music of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, sometimes as a natural result of composing in a Jewish style but occasionally in terms of parody, pathos or cultural references as well.[16][2][17] Its reduced popularity in Yiddish song due to the influence of Western music on musical tastes has been observed both in the Soviet Union and the United States by the 1940s.[6][2]

This scale is very common in Klezmer music as well. According to Feldman, it is especially present in what he calls the "transitional" klezmer repertoire, a subset of repertoire which is highly influenced by Romanian and Greek music, and not as common among the older "core" klezmer repertoire.[18][19] In particular, it is associated with the Doina, a type of freeform Romanian piece which became popular in klezmer music, an association noted by Beregovski in the 1940s.[4][6] In religious Jewish music, it is considered a "secondary" mode, as it often appears in passing in larger works with complex melodic development, rather than being the basis of an entire piece.[20][21][22]

Romanian music

[edit]Romania and Moldova, which correspond to the historical Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, played a key role in historical exchanges between Western and Ottoman music, including Roma musicians from there who played at the Ottoman court, as well as the interplay of Greek, Jewish, Romanian and Roma musical cultures.[11][7] In the musical cultures there, especially in Moldavia, this scale was commonly used in dances and songs, including in particular the Doina and various ballads, and persists today in Romanian folk music.[7]

Greek music

[edit]In Greek music, modes are called Dromoi (δρόµοι), and have names and forms which come from the Ottoman makam system, although in some cases the names no longer correspond to the original Ottoman ones.[23][24][25] There does not seem to be a universal name for this scale in the Greek context; various names are used, including Karagouna, Romanikos, Nikriz or Piraeotiko minore (Piraeus minor).[7][4]

This scale appears in a variety of types of Greek popular music, including Rebetiko and Laïko.[7] As in other regional music, the fourth degree is often flattened or raised alternately within a single piece.[25] Feldman has observed that instrumental melodies shared between Greek and Ashkenazic Jewish traditions are very often composed in this scale.[26]

Orchestral and contemporary music

[edit]The Ukrainian Dorian scale most often appears in classical music or modern compositions in pieces which draw on, or refer to, Jewish, Romanian, Ukrainian, or other ethnic music styles. Composers from the Jewish art music movement employed it, including Joseph Achron in his Hebrew Melody (1912); others from that movement including Lazare Saminsky rejected its use in compositions.[27][28] Modern American Jewish composers have also employed it, including George Gershwin, Max Helfman, Irving Berlin, Kurt Weill and Ernest Bloch.[29][30][31] Dmitri Shostakovich also employed this scale when referencing Jewish themes.[32][33] The scale is also widely used in the works of composers drawing on Romanian themes, such as George Enescu, Béla Bartók, Nicolae Bretan and Ciprian Porumbescu, as well as Ukrainian themes in works by composers like Zhanna Kolodub and Myroslav Skoryk.[34][35][36][37]

See also

[edit]- Minor gypsy scale

- Hungarian minor scale

- Phrygian dominant scale

- Double harmonic scale

- Melodic minor scale

- Mixolydian mode § Moloch scale

- Hemavati, the Indian Carnatic music corresponding to Ukrainian Dorian scale.

References

[edit]- ^ Tarsi, Boaz (2017). "At the Intersection of Music Theory and Ideology: A. Z. Idelsohn and the Ashkenazi Prayer Mode Magen Avot". Journal of Musicological Research. 36 (3): 208–233. doi:10.1080/01411896.2017.1340033. ISSN 0141-1896.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Slobin, Mark (1980). Talmage, Frank (ed.). "The Evolution of a Musical Symbol in Yiddish Culture". Studies in Jewish Folklore. Cambridge, MA: 313–330.

- ^ a b Idelsohn, Abraham Zevi (1967). Jewish Music in its Historical Development (First Schocken ed.). New York: Shocken Books. pp. 184–91.

- ^ a b c d e Rubin, Joel (1997). Stanton, Steve; Knapp, Alexander (eds.). "Alts nemt zikh fun der doyne (Everything comes from the doina): The Romanian-Jewish Doina: A Closer Stylistic Examination". Proceedings of the First International Conference on Jewish Music. London: City University Print Unit: 133–64.

- ^ a b Rubin, Joel (2020). "Notes". New York klezmer in the early twentieth century: the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras (1 ed.). Rochester (NY): University of Rochester Press. pp. 290–391. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beregovski, Moshe (2000). "5. The Altered Dorian Scale in Jewish Folk Music (On the question of the semantic characteristics of scales), 1946". In Slobin, Mark (ed.). Old Jewish Folk Music: The Collections and Writings of Moshe Beregovski (First Syracuse University Press ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. pp. 549–67. ISBN 0815628684.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Manuel, Peter (1989). "Modal Harmony in Andalusian, Eastern European, and Turkish Syncretic Musics". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 21: 70–94. doi:10.2307/767769. ISSN 0740-1558. JSTOR 767769.

- ^ Feldman, Walter Z. (1994). "Bulgărească/Bulgarish/Bulgar: The transformation of a klezmer dance genre." (): ". Ethnomusicology: 1–35. doi:10.2307/852266. JSTOR 852266.

- ^ a b c Feldman, Walter Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history, and memory. New York: Oxford university press. p. 383. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Samson, John (2015). "South East Europe". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.2274378. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b Slobin, Mark (1996). Tenement songs: the popular music of the Jewish immigrants. Urbana, Ill.: Univ. of Illinois Press. pp. 185–93. ISBN 9780252065620.

- ^ Ling, Jan (1997). A history of European folk music. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. pp. 85–6. ISBN 1878822772.

- ^ Baley, Virko; Hrytsa, Sofia (2001). "Ukraine". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40470. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Soroker, Jakov Lʹvovič (1995). Ukrainian musical elements in classical music. Edmonton: Canadian Inst. of Ukrainian Studies Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9781895571066.

- ^ Wohlberg, Max (1977). "The Music of the Synagogue as a Source of the Yiddish Folksong". Musica Judaica. 2 (1): 36. ISSN 0147-7536. JSTOR 23687445.

- ^ Heskes, Irene (1984). "Music as Social History: American Yiddish Theater Music, 1882-1920". American Music. 2 (4): 73–87. doi:10.2307/3051563. ISSN 0734-4392. JSTOR 3051563.

- ^ Heskes, Irene; Marwick, Lawrence (1992). Yiddish American popular songs, 1895 to 1950 : a catalog based on the Lawrence Marwick roster of copyright entries. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. xxiii. hdl:2027/msu.31293011839010.

- ^ Feldman, Walter Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history, and memory. New York: Oxford university press. p. 219. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Feldman, Walter Zev (2022). "Musical Fusion and Allusion in the Core and the Transitional Klezmer Repertoires". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 40 (2): 143–166. doi:10.1353/sho.2022.0026. ISSN 1534-5165.

- ^ Levine, Joseph A. (2000). Synagogue song in America (1st ed.). Northvale, NJ: Aronson. p. 205. ISBN 0765761394.

- ^ Tarsi, Boaz (2002). "Observations on Practices of "Nusach" in America". Asian Music. 33 (2): 175–219. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 834350.

- ^ Tarsi, Boaz (2020). "Uncovering the music theory of the Ashkenazi liturgical music:'Adonai Malach'as a case study". Analytical Approaches to World Music. 8 (2): 195–234.

- ^ Dietrich, Eberhard (1987). Das Rebetiko: eine Studie zur städtischen Musik Griechenlands (in German). Hamburg: K. D. Wagner. pp. 131–62. ISBN 3889790348.

- ^ Ordoulidis, Nikos (2011). "The Greek Popular Modes". British Postgraduate Musicology. 11.

- ^ a b Pennanen, Risto Pekka (1997). "The Development of Chordal Harmony in Greek Rebetika and Laika Music, 1930s to 1960s". British Journal of Ethnomusicology. 6: 65–116. doi:10.1080/09681229708567262. ISSN 0968-1221. JSTOR 3060831.

- ^ Feldman, Walter Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history, and memory. New York: Oxford university press. pp. 359–60. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Loeffler, James (2010). The Most Musical Nature. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780300162943.

- ^ Moricz, Klara (2008). "2. Zhidï and Yevrei in a Neonationalist Context". Jewish Identities: Nationalism, Racism, and Utopianism in Twentieth-Century Music. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 55–92.

- ^ Gottlieb, Jack (2004). "12. Affinities Between Jewish Americans and African Americans". Funny, It Doesn't Sound Jewish: How Yiddish Songs and Synagogue Melodies Influenced Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, and Hollywood. State University of New York Press. pp. 193–223. doi:10.1353/book10142. ISBN 978-0-7914-8502-6.

- ^ Pollack, Howard (2006). George Gershwin: his life and work. Berkeley Los Angeles London: University of California press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-520-24864-9.

- ^ Walden, Joshua S. (Fall 2012). "An essential expression of the people": interpretations of hasidic song in the composition and performance history of Ernest Bloch's Baal Shem". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 65 (3). University of California Press: 777–820. doi:10.1525/jams.2012.65.3.777.

- ^ Braun, Joachim (1985). "The Double Meaning of Jewish Elements in Dimitri Shostakovich's Music". The Musical Quarterly. 71 (1): 68–80. doi:10.1093/mq/LXXI.1.68. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 948173.

- ^ Brown, Stephen C. (2006). "Tracing the Origins of Shostakovich's Musical Motto". Intégral. 20: 69–103. ISSN 1073-6913. JSTOR 40214029.

- ^ Walden, Joshua S. (2014). Sounding authentic: the rural miniature and musical modernism. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780199334667.

- ^ Wood, Charles (2008). The one-act operas of Nicolae Bretan : Romania's silenced composer. Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Muller. p. 87. ISBN 9783639088861.

- ^ Bentoiu, Pascal (2010). Masterworks of George Enescu. Scarecrow Books. p. 297. ISBN 9780810876903.

- ^ Gnativ, Dymitro (Fall 2022). "Listening to Ukraine: A Primer". Flutist Quarterly. 48 (1). National Flute Association, Inc.