Southern Ming

Great Ming | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1644–1662 | |||||||||||

Various regimes of the Southern Ming, November 1644 | |||||||||||

| Status | Rump state of the Ming dynasty | ||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1644–1645 | Hongguang Emperor | ||||||||||

• 1645–1646 | Longwu Emperor | ||||||||||

• 1646–1647 | Shaowu Emperor | ||||||||||

• 1646–1662 | Yongli Emperor | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Transition from Ming to Qing | ||||||||||

• Li Zicheng captured Beijing | 1644 | ||||||||||

• Hongguang Emperor enthroned in Nanjing | 1644 | ||||||||||

• Death of Yongli Emperor | 1662 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | People's Republic of China Republic of China Myanmar | ||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

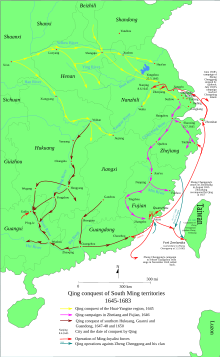

The Southern Ming (Chinese: 南明; pinyin: Nán Míng), also known in historiography as the Later Ming (simplified Chinese: 后明; traditional Chinese: 後明; pinyin: Hòu Míng), officially the Great Ming (Chinese: 大明; pinyin: Dà Míng), was an imperial dynasty of China and a series of rump states of the Ming dynasty that came into existence following the Jiashen Incident of 1644. Peasant rebels led by Li Zicheng who founded the short-lived Shun dynasty captured Beijing and the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide. The Ming general Wu Sangui then opened the gates of the Shanhai Pass in the eastern section of the Great Wall to the Qing banners, in hope of using them to annihilate the Shun forces. Ming loyalists fled to Nanjing, where they enthroned Zhu Yousong as the Hongguang Emperor, marking the start of the Southern Ming. The Nanjing regime lasted until 1645, when Qing forces captured Nanjing. Zhu fled before the city fell, but was captured and executed shortly thereafter. Later figures continued to hold court in various southern Chinese cities, although the Qing considered them to be pretenders.[1]

The Nanjing regime lacked the resources to pay and supply its soldiers, who were left to live off the land and pillaged the countryside.[note 1] The soldiers' behavior was so notorious that they were refused entry by those cities in a position to do so.[3] Court official Shi Kefa obtained modern cannons and organized resistance at Yangzhou. The cannons mowed down a large number of Qing soldiers, but this only enraged those who survived. After the Yangzhou city fell in May 1645, the Manchus started a general massacre pillage and enslaved all the women and children in the notorious Yangzhou massacre. Nanjing was captured by the Qing on June 6 and the Hongguang Emperor was taken to Beijing and executed in 1646.

The literati in the provinces responded to the news from Yangzhou and Nanjing with an outpouring of emotion. Some recruited their own militia and became resistance leaders. Shi was lionized and there was a wave of hopeless sacrifice by loyalists who vowed to erase the shame of Nanjing. By late 1646, the heroics had petered out and the Qing advance had resumed. Notable Ming "pretenders" held court in Fuzhou (1645–1646), Guangzhou (1646–1647), and Anlong (1652–1659). The Yongli Emperor was the last and also the longest reigning Emperor of the dynasty (1646–1662) and managed to fight against the Qing forces alongside the peasant armies in southwestern China prior to his capture in Myanmar in 1662. The Prince of Ningjing, in the Kingdom of Tungning (based in present-day Tainan, Taiwan) claimed to be the rightful successor to the throne of Ming until 1683, although he lacked real political power.[note 2]

The end of the Ming and the subsequent Nanjing regime are depicted in The Peach Blossom Fan, a classic of Chinese literature. The upheaval of this period, sometimes referred to as the Ming–Qing cataclysm, has been linked[citation needed] to a decline in global temperature known as the Little Ice Age. With agriculture devastated by a severe drought, there was manpower available for numerous rebel armies.

Background

[edit]The fall of the Ming and the Qing conquest that followed was a period of catastrophic war and population decline in China. China experienced a period of extremely cold weather from the 1620s until the 1710s.[6] Some modern scholars link the worldwide drop in temperature at this time to the Maunder Minimum, an extended period from 1645 to 1715 when sunspots were absent.[7] Whatever the cause, the change in the climate reduced agricultural yields and cut state revenue. It also led to drought, which displaced many peasants. There were a series of peasant revolts in the late Ming, culminating in a revolt led by Li Zicheng which captured Beijing in 1644.

Ming ideology emphasized authoritarian and centralized administration, referred to as "imperial supremacy" or huángjí. However, comprehensive central decision-making was beyond the technology of the time.[8] The principle of uniformity meant that the lowest common denominator was often selected as the standard. The need to implement change on an empire-wide basis complicated any effort to reform the system, leaving administrators helpless to respond in an age of upheaval.

Civil servants were selected by an arduous examination system which tested knowledge of classic literature. While they might be adapt at citing precedents from the Zhou dynasty of righteous and unrighteous behavior, they were rarely as knowledgeable when it came to contemporary economic, social, or military matters. Unlike previous dynasties, the Ming had no prime minister. So when a young ruler retreated to the inner court to enjoy the company of his concubines, power devolved to the eunuchs.[9] Only the eunuchs had access to the inner court, but the eunuch cliques were distrusted by the officials who were expected to carry out the emperor's decrees. Officials educated at the Donglin Academy were known for accusing the eunuchs and others of a lack of righteousness.

On April 24, 1644, Li's soldiers breached the walls of the Ming capital Beijing. The Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide the next day to avoid humiliation at their hands. Remnants of the Ming imperial family and some court ministers then sought refuge in the southern part of China and regrouped around Nanjing, the Ming auxiliary capital, south of the Yangtze River. Four different power groups thus emerged:

- The Great Shun (大順), led by Li Zicheng, ruled north of the Huai river.

- The Great Xi (大西), led by Zhang Xianzhong, controlled Sichuan province.

- The Manchu-led Great Qing (大清) controlled the north-east area beyond Shanhai Pass, as well as many of the Mongol tribes.

- The remnants of the Ming dynasty could only survive south of the Huai River, known retroactively as the Southern Ming.

Ming loyalist Muslims in the Northwest

[edit]In 1644, Muslim Ming loyalists in Gansu led by Muslim leaders Milayin (米喇印)[10] and Ding Guodong (丁國棟) led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore Zhu Shichuan, Prince of Yanchang to the throne as the emperor.[11] The Muslim Ming loyalists were supported by Hami's Sultan Sa'id Baba (巴拜汗) and his son Turumtay (土倫泰).[12][13][14] The Muslim Ming loyalists were joined by Tibetans and Han Chinese in the revolt.[15] After fierce fighting, and negotiations, a peace agreement was agreed on in 1649, and Milayan and Ding nominally pledged allegiance to the Qing and were given ranks as members of the Qing military.[16] When other Ming loyalists in southern China made a resurgence and the Qing were forced to withdraw their forces from Gansu to fight them, Milayan and Ding once again took up arms and rebelled against the Qing.[17] The Muslim Ming loyalists were then crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin, Ding Guodong, and Turumtay killed in battle.

The Confucian Hui Muslim scholar Ma Zhu (1640–1710) served with the Southern Ming loyalists against the Qing.[18] Zhu Yu'ai, Prince of Gui was accompanied by Hui refugees when he fled from Huguang to the Burmese border in Yunnan and as a mark of their defiance against the Qing and loyalty to the Ming, they changed their surname to "Ming".[19]

The Nanjing court (1644–1645)

[edit]When the news of the Chongzhen emperor's death reached Nanjing in May 1644, the fate of the heir apparent was still unknown.[20] But court officials quickly agreed that an imperial figure was necessary to rally loyalist support. In early June, a caretaker government led by the Prince of Fu was created.[21][note 3] By the time he arrived in the vicinity of Nanjing, the prince could already count on the support of both Ma Shiying and Shi Kefa.[22] He entered the city on June 5 and accepted the title "protector of the state" the next day.[23] Prodded by some court officials, the Prince of Fu immediately begin to consider ascending the throne.[24] The prince had a problematic reputation in terms of Confucian morality, so some members of the Donglin faction suggested the Prince of Lu as an alternative. Other officials noted that the Prince of Fu, as next in line by blood, was clearly the safer choice. In any case, the so-called "righteousness" faction was not keen to risk a confrontation with Ma, who arrived in Nanjing with a large fleet on June 17.[25] The Prince of Fu was crowned as the Hongguang emperor on June 19.[25][26] It was decided that the next lunar year would be the first year of the Hongguang reign.

The Hongguang court proclaimed that its goal was "to ally with the Tartars to pacify the bandits," that is, to seek cooperation with Qing military forces in order to annihilate rebel peasant militia led by Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong.[27]

Because Ma was the emperor's main supporter, he started to monopolize the royal court's administration by reviving the functions of the remaining eunuchs. This resulted in rampant corruptions and illegal dealings. Moreover, Ma engaged in intense political bickering with Shi, who was affiliated with the Donglin movement.

This displacement of troops facilitated the Qing capture of Yangzhou. This resulted in the Yangzhou massacre and the death of Shi in May 1645. It also led directly to the demise of the Nanjing regime. After the Qing armies crossed the Yangtze River near Zhenjiang on June 1, the emperor fled Nanjing. Qing armies led by the Manchu prince Dodo immediately moved toward Nanjing, which surrendered without a fight on June 8, 1645.[28] A detachment of Qing soldiers then captured the fleeing emperor on June 15, and he was brought back to Nanjing on June 18.[29] The fallen emperor was later transported to Beijing, where he died the following year.[29][30]

The official history, written under Qing sponsorship in the eighteenth century, blames Ma's lack of foresight, his hunger for power and money, and his thirst for private revenge for the fall of the Nanjing court.

Zhu Changfang, Prince of Lu, declared himself regent in 1645, but surrendered the next year.[31]

The Fuzhou court (1645–1646)

[edit]

In 1644, Zhu Yujian was a ninth-generation descendant of Zhu Yuanzhang who had been put under house arrest in 1636 by the Chongzhen emperor. He was pardoned and restored to his princely title by the Hongguang emperor.[32] When Nanjing fell in June 1645, he was in Suzhou en route to his new fiefdom in Guangxi.[33] When Hangzhou fell on July 6, he retreated up the Qiantang River and proceeded to Fujian from a land route that went through northeastern Jiangxi and mountainous areas in northern Fujian.[34] Protected by General Zheng Hongkui, on July 10 he proclaimed his intention to become regent of the Ming dynasty, a title that he formally received on July 29, a few days after reaching Fuzhou.[35] He was enthroned as emperor on August 18, 1645.[35] Most Nanjing officials had surrendered to the Qing, but some followed the Prince of Tang in his flight to Fuzhou.

In Fuzhou, the Prince of Tang was under the protection of Zheng Zhilong, a Chinese sea trader with exceptional organizational skills who had surrendered to the Ming in 1628 and recently been made an earl by the Hongguang emperor.[36] Zheng Zhilong and his Japanese wife Tagawa Matsu had a son, Zheng Sen. The pretender, who was childless, adopted Zheng Zhilong's eldest son Zheng Sen, granted him the imperial surname, and gave him a new personal name: Chenggong.[37] The name Koxinga is derived of his title "lord of the imperial surname" (guóxìngyé).[37]

In October 1645, the Longwu Emperor heard that another Ming pretender, Zhu Yihai, Prince of Lu, had named himself regent in Zhejiang, and thus represented another center of loyalist resistance.[37] But the two regimes failed to cooperate, making their chances of success even lower than they already were.[38]

In February 1646, Qing armies seized land west of the Qiantang River from the Lu regime and defeated a ragtag force representing the Longwu emperor in northeastern Jiangxi.[39] In May of that year Qing forces besieged Ganzhou, the last Ming bastion in Jiangxi.[40] In July, a new Southern Campaign led by Manchu Prince Bolo sent the Zhejiang regime of Prince Lu into disarray and proceeded to attack the Longwu regime in Fujian.[41] Zheng Zhilong, the Longwu emperor's main military defender, fled to the coast.[41] On the pretext of relieving the siege of Ganzhou in southern Jiangxi, the Longwu court left their base in northeastern Fujian in late September 1646, but the Qing army caught up with them.[42] Longwu and his empress were summarily executed in Tingzhou (western Fujian) on 6 October.[43] After the fall of Fuzhou on 17 October, Zheng Zhilong defected to the Qing but his son Koxinga continued to resist.[43] Through Zheng networks, the Southern Ming continued to enjoy a privileged diplomatic position vis-a-vis Tokugawa Japan, who exempted Southern Ming ships from the ban on exports of weapons and strategic materials, and from the ban on Japanese wives of Southern Ming Chinese men remaining in Japan. The Zheng were also able to recruit Japanese troops, particularly from their strongest sympathizers, the Satsuma and Mito domains.[44]

The Guangzhou court (1646–1647)

[edit]

The Longwu Emperor's younger brother Zhu Yuyue, who had fled Fuzhou by sea, soon founded another Ming regime in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong Province, proclaiming the era of Shaowu (紹武) on 11 December 1646.[45] Short of official costumes, the court had to purchase robes from local theater troupes.[45] On 24 December, Zhu Youlang, Prince of Gui established the Yongli (永曆) regime in the same vicinity.[45] The two Ming regimes fought each other until 20 January 1647, when a small Qing force led by former Southern Ming commander Li Chengdong (李成棟) captured Guangzhou, causing the Shaowu Emperor to commit suicide, and sending the Yongli emperor fleeing to Nanning in Guangxi.[46]

The Portuguese in Macao provided military aid in the form of cannons to the two courts established by the Princes of Gui and Tang in exchange for tax exemption, more land around Macao and conversions to Catholicism.[47] The Empress dowager, the two Empresses and the crown prince converted to Catholicism, and the Jesuit missionaries carried letters to the Pope and the Portuguese asking for aid.[48]

The Nanning court (1646–1651)

[edit]

Li Chengdong suppressed more loyalist resistance in Guangdong in 1647, but mutinied against the Qing in May 1648 because he resented having been named only regional commander of the province he had conquered.[49] The concurrent rebellion of another former Ming general in Jiangxi helped the Yongli regime to retake most of southern China, leaving the Qing in control of only a few enclaves in Guangdong and southern Jiangxi.[50] But this resurgence of loyalist hopes was short-lived. New Qing armies managed to reconquer the central provinces of Huguang (present-day Hubei and Hunan), Jiangxi, and Guangdong in 1649 and 1650.[51] The Yongli emperor fled to Nanning and from there to Guizhou.[51] On 24 November 1650, Qing forces led by Shang Kexi – the father of one of the "Three Feudatories" who would rebel against the Qing in 1673 – captured Guangzhou after a ten-month siege and massacred the city's population, killing as many as 70,000 people.[52]

Yunnan and Burma exile (1651–1661)

[edit]Though the Qing under the leadership of Prince Regent Dorgon (1612–1650) had successfully pushed the Southern Ming deep into southern China, Ming loyalism was not dead yet. In early August 1652, Li Dingguo, who had served as general in Sichuan under bandit king Zhang Xianzhong (d. 1647) and was now protecting the Yongli emperor, retook Guilin (Guangxi province) from the Qing.[53] Within a month, most of the commanders who had been supporting the Qing in Guangxi reverted to the Ming side.[54] Despite occasional successful military campaigns in Huguang and Guangdong in the next two years, Li failed to retake important cities.[53]

In 1653, the Qing court put Hong Chengchou in charge of retaking the southwest.[55] Headquartered in Changsha (in what is now Hunan province), he patiently built up his forces; only in late 1658 did well-fed and well-supplied Qing troops mount a multipronged campaign to take Guizhou and Yunnan.[55] In late January 1659, a Qing army led by Manchu prince Doni took the capital of Yunnan, sending the Yongli emperor fleeing into nearby Burma, which was then ruled by King Pindale Min of the Toungoo dynasty.[55] The last sovereign of the Southern Ming stayed there until 1662, when he was captured and executed by Wu Sangui, whose surrender to the Qing in April 1644 had allowed Dorgon to start the Qing conquest of Ming.[56]

In the late summer of 1664, Li Lai-heng and his remaining followers were surrounded on one of these mountains. Unable to escape, Li gave orders to build a fire and then threw himself into the flames.

Kingdom of Tungning (1661–1683)

[edit]

Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), son of Zheng Zhilong, was awarded with the titles: Marquis of Weiyuan, Duke of Zhang, and Prince of Yanping by the Yongli Emperor.

Koxinga then decided to take Taiwan from the Dutch. He launched the Siege of Fort Zeelandia, defeating the Dutch and driving them out of Taiwan. He then established the Kingdom of Tungning on the site of the former Dutch colony. The Ming princes who accompanied Koxinga to Taiwan were Zhu Shugui, Prince of Ningjing and Zhu Honghuan, son of Zhu Yihai, Prince of Lu.

Koxinga's grandson Zheng Keshuang surrendered to the Qing dynasty in 1683 and was rewarded by the Kangxi Emperor with the title Duke of Hanjun and he and his soldiers were inducted into the Eight Banners.[57][58][59] The Qing sent the 17 Ming princes still living on Taiwan back to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives.[60] Zheng Zhilong wrote "Grand Strategy for ordering the country". He argued that for the Southern Ming to retake the country, they should do it through regional military commanders all across China's provinces and not in a centralized fashion. This brought him at loggerheads with the Longwu Emperor. Famine also struck after drought and corps failed all along the southeastern coastal region. This led to outbreaks of banditry. Ports under Zheng Zhilong's control were running out of raw silk due to the Yangzi river delta under attack by the Qing. The Longwu emperor wanted the take over Huguang and Jiangxi provinces which were major producers of rice to help boost the southern Ming. Zhilong refused to expand out of Fujian to keep his control over the movement.[61]

Zheng tried to solve the problem by extorting and taxation and then seeking aid from Tokugawa Japan. He tried to solve the problem by extorting and taxation and then seeking aid from Tokugawa Japan. Sekisai Ugai said that Zheng Zhilong's brother had 1,000 musket armed Japanese mercenaries. The Tokugawa shogun received two requests for samurai mercenaries and weapons in Nagasaki in 1645-1646 from Zheng Zhilong. The Tokugawa Bakufu originally urged Japanese women who were married to Chinese men, to leave Japan when they enacted the maritime ban (after which was passed, they would not be allowed to leave Japan), but a lot of Japanese women who were married to Chinese men like Tagawa Matsu remained in Japan and did not leave when the ban was enacted. The Tokugawa allowed them to stay unlike how they violently ejected the Japanese wives and children of Europeans. After the ban was first passed five years elapsed until Zheng requested his Japanese wife Tagawa be allowed to come to China and they were unsure if they would let her come in violation of the maritime ban. The Tokugawa Shogunate decided to allow Tagawa Matsu, his Japanese wife to violate the ban, leave Japan and reunite with him in China. Zheng Zhilong and one of his underlings, Zhou Ghezhi, both had connections to daimyo and the bakufi after living in Japan. Zhou Hezhi sent a letter on the first request for help and the next one was sent to the Kyto-based Japanese Emperor and the Edo-based Tokugawa Shogun along with gifts from Zheng Zhilong.[62]

Zheng Zhilong informed the Tokugawa Bakufu on how his son Koxinga rose through the ranks of the Ming military and asked for ten slaves and ...... in waiting and Shichizaemon to be allowed to come to China from Japan to help take care of his wife Tagawa Matsu. Although the requests were rejected officially by the bakufu, a lot of Japanese in the Tokugawa government privately supported going to war against the Manchus and support the Ming. Samurai and daimyo were to be subjected to full scale mobilization and attack routes along the coast of China were planned by the Tokugawa shogunate. It was the Qing take over of Fuzhou in 1646 which caused the plans to be cancelled. Further requests came between 1645 and 1692. Food and financial shortage led to abandonment of the Jiangxi-Fujian and Zhejiang-Fujian mountain passes by Zheng Zhilong because he could not afford to pay salaries or feed his soldiers all over Fujian. His soldiers were sent to guard the coast. He started negotiations with the Qing and the Shunzhi Emperor officially appointed him as ruler over Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang as "King of Three Provinces". However it asked Zhilong to come to Beijing to meet Shunzhi.[63]

Zheng Zhilong refused to go because he most likely though it was a trap. Zheng Zhilong commanded his army not to fight against the Qing as they took over Fuzhou after coming into Fujian in 1646. The Longwu emperor was either killed or escaped and was never again found as he tried to escape to Jiangxi. The Qing invited Zheng Zhilong to a banquet for negotiations. His son Koxinga and brother Zheng Hongkui cried and beseeched Zheng Zhilong not to go. He had 500 war junks and army which he could still use to rule. They also knew of the queue order.[64]

Tagawa Matsu was ..... by the Manchus according to one account and she committed suicide. One confused Chinese account said that Koxinga cut out his mother's intestines and washed them, following the "barbarian" (Japanese) custom.[65] This may have referred to sepukku. Koxinga referred to the queue order, saying "no person, wise or stupid, is willing to become a slave with a head that looks like a fly" and he wanted revenge against the Qing for the death of his mother. Koxinga was conflicted by filial piety and loyalty but never allowed himself to be used and used others. He gained control over thousands of men after originally having only 300. Koxinga's uncles Zheng Zhiwan and Zheng Hongkui pledged allegiance to him and his revenue came from the commercial network of his father Zheng Zhilong. He rallied in Anhai on the coast. Koxinga did not recognize the Prince of Lu as the Emperor and instead continued to use the reign title of the Longwu emperor in contrast to other coastal southeastern warlords. There was hostility between the prince of Lu and Longwu during their reigns and he did not want to have a powerful authority figure with him. He later pledged allegiance to the Yongli Emperor, Prince Zhu Youlang.[66] Koxinga's goals were a Ming dynasty retaking control over China with himself as an autonomous feudal lord in control of Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Fujian on the coastal southeastern area. This may have been similar to the Tokugawa bakufu which controlled Japan while the emperor reigned and he was referred to as a feudatory by his followers and himself with the title "Generalissimo Who Summons and Quells" which was similar to the "barbarian-quelling generalissimo" title of the shogun. The Chinese mufu (tent government) was the model for the bakufu in Japan. Koxinga was an idealist who fought for restoring the Ming before 1651 but the disaster at Xiamen changed his tactics.[67] Koxinga's uncles Zheng Hongkui and Zheng Zhiwan had allowed the Qing to attack and pillage Xiamen without a fight after the Qing threatened they would harm Zheng Zhilong and his family who were under house arrest in Beijing. This was directly disobeyed Koxinga's orders, while Koxinga was on his way to help the Yongli emperor. Because the uncles had their own command chain in their armies and they were of the older generation than Koxinga they decided they had the right to violate standing orders Koxinga's men forced him to turn back after they heard what happened to their homes and families in Xiamen so he returned. Zheng Zhiwan and his staff were executed by Koxinga and his own army absorbed Zhiwan's troops. Because Zheng Hongkui sided with Koxinga most of the time and was nice to him before he was not executed but he was scared and went into retirement, giving up control over his troops to Koxinga. He died in 1654 after living on an island for the rest of his life. Shi Lang had warned that Xiamen could be subjected to attack so Shi Lang's arrogance and habit of disobeying orders grew. Koxinga responded by jailing his brother, his father, and him on a ship in 1651 for violating orders. Shi Lang defected to the Qing after breaking out of the ship. Shi Lang's family was then executed by Koxinga. Koxinga then started the build up his organization and strengthening it and going through formal rituals to pay allegiance to the Yongli Emperor.[68] Koxinga's underlings were people who used to work for his father and his family. They were very experienced at trading and sailing and familiar with the inlets and harbors of the coast of Minnan where they grew up and were merchants and military men. One of them was a pirate partner of Zhilong, Hong Xu. Wang Zhongxiao and Li Maochun, who were gentry of Minnan, and Xu Fuyuan, a bureaucrat in the Ming government were among the number of people in Koxinga's organization. Prince of Ningjing Zhu Shugui, the prince of Lu and other Ming princes came in 1652 with Zhang Huangyan and Zhang Mingzhen, part of the anti-Qing resistance. A separate command chain was kept by Zhang Huangyan and Zhang Mingzhen and the military men and merchants were looked down upon by the elites. There were regional rivalries between Koxinga's Minnan followers and the Zhejiang followers of the two Zhangs.[69]

The Prince of Lu was also treated as their real ruler by the Zhejiang gentry leaders while Yongli was officially regarded as their emperor. In 1652 the Prince of Lu gave up his titles under Koxinga's pressure. Koxinga sent him to Penghu and did not reinstate his titles in 1659 when the Yongli emperor ordered that they be. The Tingzhou Hakka Liu Guoxuan, former Zhangzhou vice-garrison commander for the Qing, and the former Taizhou military commander for the Qing, northern Chinese Ma Xin defected to Koxinga's side. They rose to high ranks under Koxinga over his own Minnanese people because Koxinga held all power over them since they had no local base because they could not speak the dialects of coastal Fujian, where they were not born in. They were familiar with infantry war on land and knew how to fight the Qing. Most of his labor, taxpayers, sailors, and infantry troops were local Fujian coastal people.[70] The Qing and Ming dynasty were based on the continent and stymied the activities of the coast while shipbuilding, cash cropping, sea trade, salt, and fishing were stimulated by Koxinga's rule. Koxinga, from his Jinmen and Xiamen island bases, went on the offensive, killing Zhejiang and Fujiang Qing governor-general Chen Jin, blockading Quanzhou, and taking over most of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou's counties in 1652. He controlled crucial coastal strips and islands on the Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang coast where maritime trade occurred. The Yongli court was earlier regarded as more threatening by the Qing but now their attention was turned to the southeast coast by Koxinga's victories. The Qing were in no way ready to build a navy because of a lack of money and time. The Shunzhi emperor was more open to negotiations after regent Dorgon died in 1652. A ceasefire was issued by Shunzhi in 1653 after negotiations were started. He then sent Koxinga edicts.[71] The Qing used Zheng Zhilong to send messages to his son and monitored the communications during negotiations. Koxinga rejected offers by the Qin, saying to his father "since my father has erred in front, how can I follow your footsteps?" The Qing offered him the status of Geng Jimao and Shang Kexi's Guangdong feudatories. He had to pay customs duties to the Qing while maintaining control of his maritime trading organization, the Qing would appoint civil officials in the four prefectures of Huizhou, Chaozhou, Quanzhou, and Zhangzhou which he would take control of while he would still command his army. The Qing ordered him to adopt the queue if he wanted to receive this deal. Adopting the queue could trigger revolt in his army if he conceded. Koxinga rejected the queue order and said that he would accept the same status of Korea, maintaining their hair and clothing and to "adopt the Qing calendar ... if not for the sake of the land and its mortals, then to bend on behalf of my father." if the Qing wanted him to agree to the 4 prefectures deal. Koxinga also said that if the Qing gave him what they offered to his father, total control of Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Fujiand, he would agree to adopt the queue. Negotiations were then terminated by the Qing after this counter-offer was rejected.[72] European clothes were worn by Ma Xin when he fought. Koxinga held horseback riding and archery practice for coastal troops and naval practice for inland troops during training when they were not fighting. Confucian education and a stipend were provided for family of officers who died by the "Hall for Nourishing Descendants" in Xiamen. Koxinga implemented severe punishments and discipline for disobeying orders and other wrongs, like beatings, poisoning, forced suicide, and decapitation. If one of his underlings won a battle after they were given a suspended death sentence it could be lifted. There were also rewards which led to good battlefield performance. There was a dearth of food supply. Families of gentry, Ming princes, soldiers, and officers not engaged in work numbered 300,000 which he had to support with food. 1,500 soldiers in one southern Fujian town put a strain on food supply. They tried to solve the problem by looting Qing controlled prefectures for grain and raided Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Fujian 44 times in 1649–1660.[73] Zheng forbade .... of women and said the rich should be plundered first by his soldiers. "Voluntary offers", "donations" and bullion and grain tax were extracted from people he ruled by Koxinga. The payments were taken to Xiamen via Haicheng port. 750,000 taels were paid by Quanzhou while 1,080,000 tales were paid by Zhangzhou in 1654. In Quanzhou and Zhangzhou his own fields were subject to intensified farming and in eastern Guangdong more farms were started by his soldiers. Koxinga seized more land during negotiations through military force and talks to take over independent militias and more land surrounding Jinmen and Xiamen. Administrative government offices were founded in 1654 by Koxinga.[74] He officially titled them as Ming extensions but he also created new offices or changed the functions of offices. His headquarters was based in Siming, the new name for Xiamen. The Zheng organization started the Six offices as a regional variation of the central Ming Six Boards with the Yongli emperor's permission, they were personnel, military, revenue, punishment, rites, and works. Yongli court held civil service exams in southwest China where Koxinga sent students to after they were educated at his Xiamen-based Confucian academy.[75] A total of 200 junks in the Western Sea Fleet and Eastern Sea Fleet reported to the five sea firms, trust, wisdom, propriety, righteousness, benevolence, reporting to the five mountain firms, earth, fire, water, wood, gold, reporting to the warehouse for nourishing the country, which reported to the Celestial Pier (Koxinga himself) or his generals and relatives who reported to the revenue office. Pass system was under the warehouse for benefiting the people which reported to private merchants which reported to the revenue office. Officials and gentry made up the workers in most offices which were only symbolic since Koxinga's forces mostly engaged in military occupation. Koxinga's mercantile followers and family made up the Revenue and Military offices. Trade and economic activity was controlled by the Revenue Office. Koxinga had 10 firms which sold and purchased products for his Celestial Pier company, which relied on funding from silver deposits with interest from the Warehouse for Nourishing the Country. In Qing areas there were branch offices conducting trade for Koxinga's five Mountain Firms. One branch office was in Beijing, and Nanjing and Suzhou had the other three which were run by assistant managers, reporting to Zeng Dinglao, chief manager at its Hangzhou headquarters. They pretended to be normal stores which trading foreign products and sending to Xiamen porcelain and silk while in Qing controlled areas. Zheng organization used gold plated bronze talleys and flag tokens for its spies, using both Buddhist monks and merchants in these firms for its spying activities. They reported on army movements by the Qing.[76]

The Ming regarded there to be two oceans, the Western Ocean and Eastern Ocean. Koxinga's firms had a fleet for each ocean made out of 60 ships, 12 junks per the 5 firms. Southeast Asia, Cambodia, Batavia, and Siam were traded with the Western Ocean Fleet, and Philippines, Dutch Taiwan, and Japan were traded with the Eastern Ocean Fleet. The junks operated in defensive quads of five or four and had cannons for defense. They two different fleets sometimes overlapped when going back. Koxinga's relative Zheng Tai owned the Dongli firm while leader of the revenue office after 1657 and his predecessors Hong Xu had the Xuyuan firm. Thousands of silver taels annually were gained through trade by Chen Yonghua. Koxinga also employed official merchants who worked for him like Zheng Tai, an adopted son of his family.[77]

Travel distance and vessel size were factors in the price of Koxinga's permits which he sold to people who wanted to engage in overseas commerce like when Zheng Zhilong ruled. Private loans ere given out by the Xiamen Warehouse for Benefiting the People. The five Sea Firms lent out ships for rent and Zheng agents also provided cargo space on their ships for a fee to private merchants. Japan bound Zheng Tai's dongli vessels also carried Celestial Pier products from Koxinga. Private businesses were also engaged in by official merchants. There was a major Southeast Asia and Japan based diaspora of Chinese with Ming loyalists and traders among them. There were official representatives of Koxinga, agents, and private traders among them. They sold permits and bought products for Koxinga and communicated between the European rulers of the colonies and Koxinga. The Revenue Office received reports from the family and patronage networks which synthesized them with the traditional bureaucracy of China.[78]

Koxinga created an economic unity of Chinese in Southeast Asia, Japan, and in the Qing. His five sea firms used its navy to escort merchants who bought his permits to avoid Dutch attacks on their ships. In China their relatives would be punished and fined if they were trading without a permit from Koxinga. Chinese merchants at ports overseas paid fees and bough licenses from his agents. There were some ships outside of his control like northern Chinese ships, Chinese, Macanese, and Portuguese in Macao, and Guangzhou based ships of Geng Jimao and Shang Kexi, feudatories of the Qing. The Japanese market and East Asian trade saw a struggle between the Dutch East India Company and Zheng organization. Japanese merchants were allowed to buy silk directly after the silk allotment guild was ended by the bakufu in 1655 [79]

In 1650-1662 Nagasaki annually received 50 Chinese ships most of which bought Koxinga passes or were his ships. They sold books, medicine, porcelain, textiles, gold, and silk. Koxinga brought animal hides from Southeast Asia, and gold and silk from Quang Nam Nguyen lord Vietnam and Tonkin Trinh Lord Vietnam. 1,563,259 silver taels worth of products were imported every year by Japan from Koxinga. Yongli coins and weapons required copper which Koxinga imported from Japan. He also imported resin, tar, cannons, muskets, armor, swords, knives, with the majority of imports at 70% being silver. Taels numbering 1,513,93 were profit out of the 2,350,386 taels Koxinga received from trading with Japan. Most of the Japanese products were used for his military or currency. They were also exported to Vietnam's civil war in Quang Nam and Tonkin. The Dutch tried to get a Chinese coastal base but could not, trying to get Chinese silk for themselves. The Zheng had a monopoly on Chinese silk and sold it at high prices to the Dutch. The Dutch obtained Tonkin silk by allying with the Trinh lords against the Nguyen Lords but it was not of consistent quality.[80]

The Dutch Bengal factory found Bengali white silk and started export to Japan in 1655. However the Chinese silk always outsold it and Koxinga's revenue was more than half of the 708,564 taels worth of products the Dutch sold in Japan annually. Dutch Taiwan exchanged silver for gold from China brought by Zheng junks. Cloth and silk from India were bought with this gold by the Dutch. Spanish Manila used American silver to buy porcelain and silk from the Zheng which were taken to the Americas and the Philippines. Dutch were not allowed to trade in Manila. The Zheng sent the silver to China or to buy products in Taiwan, Philippines, Southeast Asian islands, Vietnam, Cambodian and Siam. Timber and rice were bought by the Zheng and so were rhinoceros horns, ivory, and sappanwood to be brought to Japan and China, while deerskins, spices, pepper, and sugar were bought by both the Dutch and Zheng. The Western Ocean received 20 or 16 vessels by the Zheng each year.[81]

Violent Dutch efforts to try to undercut Zheng's organization were countered by Koxinga with alliances and diplomacy. The violence of the VOC was dampened by the laws of Tokugawa Japan. A new system of diplomatic relations was implemented by Koxinga with modifications to the tributary system used by Ming China. Japan and other maritime states with relations with Zheng organization were not previously part of the Ming system. He used "mutual dispatch of embassies according to a calendar of diplomatic ritual, cordial encounters, and equivalent treatment of these foreign rulers through regulation and practice." sizing up relations by power and status. Since the Yongli Emperor was the Zheng's overlord the Zheng organization itself could have equal diplomatic relations unlike the Ming with its tributary system placing itself at the top. Enemy states were treated as vassals as an insult by Koxinga in preparation for war. The Tokugawa Shogun Ietsuna received a diplomatic message of congratulations from Koxinga in 1651. The Zheng organization allied with Shogun Ietsuna. They were familiar with Japanese rules and were a united bloc of Chinese merchants under one leader. They served to balance against the Dutch. The Tokugawa bakufu gave asylum to Ming refugees, and allowed into Nagasaki to trade "only those Chinese merchants under anti-[Qing] auspices" after the Manchu invasion since the majority of Japanese were pro-Ming and supported Koxinga. A fake uncle-nephew protocol was used by Ietsuna according to Chinese accounts with Koxinga.[82]

Xiamen received the money from permits sold in Japan. To make it so he would take most of the trade he sold a maximum annually of 10 new permits. Payment of permits was enforced by Japanese Nagasaki magistrates. Zheng agents received custody of Wang Yunsheng after he tried using a 10 year old expired permit in Nagasaki in 1653. Wang was pardoned by Koxinga after Koxinga's brother Shichizaemon asked him to. The Japanese bakufu helped protect the Zheng network from Dutch violence through its law. Japanese Nagasaki magistrates received cases involving Dutch attacks on Koxinga ships, with Koxinga receiving help from his brother Shichizaemon in filing the cases. At the Malay peninsula around Johor, Chen Zhenguan, a Zheng agent whose junk was headed to Japan, was attacked by several Dutch ships in June 1657. The Dutch were heading for Taiwan with Chen's crew as prisoners but the Dutch ship Urk was blown to Kyushu in Japan by a storm. The Chinese sprang out and filed a case at the magistrates in Nagasaki on 23 August to the bakufu in Edo. They won the case and Japan threatened to kick out the Dutch if they attacked Japan bound junks and forced the Dutch to pay compensation to Chen. A silver tael payment of 20,000 was ordered by Japan to be paid to Chen by the Dutch in 1661. The Revenue Officer in Xiamen after 1657 was Zheng Tai, who also had been to Nagasaki and dealt with commerce related to Japan.[83]

South East Asia

[edit]The Ming loyalist Chinese pirate Yang Yandi (Dương Ngạn Địch)[84] and his fleet sailed to Vietnam to leave the Qing dynasty in March 1682, first appearing off the coast of Tonkin in northern Vietnam. According to the Vietnamese account, Vũ Duy Chí (武惟志), a minister of the Vietnamese Lê dynasty came up with a plan to defeat the Chinese pirates by sending more than 300 girls who were beautiful singing girls and prostitutes with red handkerchiefs to go to the Chinese pirate junks on small boats. The Chinese pirates and northern Vietnamese (Tonkinese) girls had sex but the women then wet the gun barrels of the pirates ships with their handkerchiefs which they got wet. They then left in the same boats. The Trinh Lords navy then attacked the Chinese pirate fleet which was unable to fire back with their wet guns. The Chinese pirate fleet, originally 206 junks, was reduced to 50–80 junks by the time it reached South Vietnam's Quang Nam and the Mekong delta. The Chinese pirates having sex with north Vietnamese women may also have transmitted a deadly epidemic from China which ravaged the Tonkin regime of north Vietnam. French and Chinese sources say a typhoon contributed to the loss of ships along with the disease.[85][86][87][88] The Nguyễn court of southern Vietnam allowed Yang (Duong) and his surviving followers to resettle in Đồng Nai, which had been newly acquired from the Khmers. Duong's followers named their settlement as Minh Huong, to recall their allegiance to the Ming dynasty.[89]

See also

[edit]- Ming dynasty

- Transition from Ming to Qing

- List of Southern Ming emperors

- History of Taiwan

- Iquan's Party

- Empress Dowager Ma (Southern Ming)

Notes

[edit]- ^ It was projected that 7 million taels would be required to fund military activity alone. Revenue of 6 million taels was anticipated based on normal receipts from the areas under Nanjing's control. Severe drought, rebellion, and unsettled conditions combined to ensure that actual revenue was only a fraction of this amount.[2]

- ^ The historical position of Koxinga's regime on Taiwan is still under debate in academia. The controversy mainly focused on whether the regime should be regarded as a direct continuation of the legitimate dynastic historiography of the Ming dynasty (including the Southern Ming), or treating it as simply an independent polity ruled by the House of Koxinga, as distinct from the rump states those founded by the imperial members of the Ming.[4][5] The Yongli Emperor was the last generally recognized sovereign of the Southern Ming before his death in 1662.

- ^ The prince was a grandson of the Wanli Emperor (r. 1573–1620). Wanli's attempt to name Yousong's father as heir apparent had been thwarted by supporters of the Donglin movement because Yousong's father was not Wanli's eldest son. Although this was three generations earlier, Donglin officials in Nanjing nonetheless feared that the prince might retaliate against them.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ See The Oxford History of Historical Writing: 1400–1800 (2011) by Jose Rabasa, p. 37.

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, pt. 1, p. 645).

- ^ Wakeman, Volume 1, p. 354.

- ^ Xing Hang (2017), "The Zheng state on Taiwan", Conflict and commerce in maritime East Asia: The Zheng family and the shaping of the modern world, c. 1620–1720, Cambridge University Press, pp. 146–175, doi:10.1017/CBO9781316401224.007, ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

- ^ Tonio Andrade; Xing Hang (2016), "Koxinga and his maritime kingdom", Sea Rovers, Silver, and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in Global History, 1550–1700, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 348–350, ISBN 978-0824852771, retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "China's 2,000 Year Temperature History Archived 2016-11-10 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Eddy, John A., "The Maunder Minimum: Sunspots and Climate in the Age of Louis XIV", The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century edited by Geoffrey Parker, Lesley M. Smith.

- ^ "Government finance under the Ming represented an attempt to impose and extremely ambitious centralized system on an enormous empire before its level of technology had made such a degree of centralization practical." Ray Huang, Taxation and Finance in Sixteenth-Century Ming China, p. 313.

- ^ Tong, James, Disorder Under Heaven: Collective Violence in the Ming Dynasty (1991), p. 112.

- ^ Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759–1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0804729338. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0295800554. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0295800554. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759–1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0804729338. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 978-3447040914. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0295800554. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Wakeman Jr., Frederic (1986). Great Enterprise. University of California Press. p. 802. ISBN 978-0520048041. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Wakeman Jr., Frederic (1986). Great Entereprise. University of California Press. p. 803. ISBN 978-0520048041. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

milayin.

- ^ Brown, Rajeswary Ampalavanar; Pierce, Justin, eds. (2013). Charities in the Non-Western World: The Development and Regulation of Indigenous and Islamic Charities. Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 978-1317938521. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Michael Dillon (2013). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Taylor & Francis. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-136-80940-8. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 641–642.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 642

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 642.

- ^ Hucker 1985, p. 149 (item 840).

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 345 and 346, note 86.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 346.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 644.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 396 and 404.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 578.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 580.

- ^ Kennedy 1943, p. 196.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2016). Encyclopedia of Chinese History. Taylor & Francis. p. 645. ISBN 978-1317817161.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 665, note 24 (ninth-generation descendant), and p. 668 (release and pardon).

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 663.

- ^ Struve 1988, pages 660 (date of the fall of Hangzhou) and 665 (route of his retreat to Fujian).

- ^ a b Struve 1988, p. 665.

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 666–667.

- ^ a b c Struve 1988, p. 667.

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 667–669 (for their failure to cooperate), 669–674 (for the deep financial and tactical problems that beset both regimes).

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 670 (seizing land west of the Qiantang River) and 673 (defeating Longwu forces in Jiangxi).

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 674.

- ^ a b Struve 1988, p. 675.

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 675–676.

- ^ a b Struve 1988, p. 676.

- ^ Xing Hang (2015), Conflict and commerce in maritime East Asia: The Zheng family and the shaping of the modern world, c. 1620–1720, Cambridge University Press, pp. 68, 104, ISBN 978-1107121843

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1985, p. 737.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 738.

- ^ Jason Buh (2021). "2.3.5 Collapse of the Ming". Global Constitutional Narratives of Autonomous Regions: The Constitutional History of Macau. Routledge. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1000369472.

- ^ Jaroslav Miller, László Kontler (2010). Friars, Nobles and Burghers – Sermons, Images and Prints: Studies of Culture and Society in Early-Modern Europe – In Memoriam István György Tóth. Central European University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-9633864609.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 760–761 (Ming resistance in late 1647) and 765 (Li Chengdong's mutiny).

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 766.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 767.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 767–768.

- ^ a b Struve 1988, p. 704.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 973, note 194.

- ^ a b c Dennerline 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 710.

- ^ Herbert Baxter Adams (1925). Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science: Extra volumes. p. 57. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ^ Pao Chao Hsieh (2013). Government of China 1644 – Cb: Govt of China. Routledge. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-1-136-90274-1. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Pao C. Hsieh (1967). The Government of China, 1644–1911. Psychology Press. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-7146-1026-9. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Manthorpe 2008, p. 108.

- ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang. [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang. [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Xing Hang (2015). [Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia January 2016 Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720]. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-107-12184-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Antony, Robert J. (June 2014). ""Righteous Yang": Pirate, Rebel, and Hero on the Sino-Vietnamese Water Frontier, 1644–1684" (PDF). Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (11): 4–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-15. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ Li, Tana (2015). "8 Epidemics, Trade, and Local Worship in Vietnam, Leizhou peninsula, and Hainan island". In Mair, Victor H; Kelley, Liam (eds.). Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbours. China Southeast Asia History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 199. ISBN 978-9814620536. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ Li, Tana (2016). "8 Epidemics, Trade, and Local Worship in Vietnam, Leizhou peninsula, and Hainan island". In Mair, Victor H (ed.). Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbours. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. ISBN 978-9814620550. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- ^ Li, Tana (28–29 June 2012). "Epidemics in late pre-modern Vietnam and their links with her neighbours 1". Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbours (organized by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: 10–11. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ 公餘捷記 • Công dư tiệp ký (R.229 • NLVNPF-0744 ed.). p. 2. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ Khánh Trần (1993), p. 15.

Sources

[edit]- Dennerline, Jerry (2002), "The Shun-chih Reign", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73–119, ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6, retrieved 2016-08-27.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985), A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-1193-7.

- Kennedy, George A. (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 195–96.

- Khánh Trần (1993). The Ethnic Chinese and Economic Development in Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789813016675. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Lin, Renchuan (林仁川) (1987), Mingmo Qingchu siren haishang maoyi 明末清初私人海上贸易 [Private Ocean Trade in the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties] (in Chinese), Shanghai, China: East China Normal University Press, CSBN: 11135.24 / F552.9, archived from the original on August 15, 2007.

- Struve, Lynn (1988), "The Southern Ming", in Frederic W. Mote; Denis Twitchett; John King Fairbank (eds.), Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 641–725, ISBN 978-0521243322, retrieved 2020-05-18.

- Wakeman, Frederic Jr. (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

External links

[edit]- Southern Ming

- States and territories established in 1644

- States and territories disestablished in 1683

- Ming dynasty

- Qing dynasty

- Dynasties of China

- Former countries in Chinese history

- Military history of the Ming dynasty

- 1644 establishments in China

- 1683 disestablishments in Asia

- 1680s disestablishments in China

- 17th century in China

- Rump states