Atlanta Braves

| Atlanta Braves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (4) | |||||

| NL Pennants (18) | |||||

| NA Pennants (4) | |||||

| NL East Division titles (18) | |||||

| NL West Division titles (5) | |||||

| Pre-modern World Series (1) | |||||

| Wild card berths (3) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Atlanta Braves Holdings, Inc. Traded as: Nasdaq: BATRA (Series A) OTCQB: BATRB (Series B) Nasdaq: BATRK (Series C) Russell 2000 components (BATRA, BATRK)[3] | ||||

| President | Derek Schiller | ||||

| President of baseball operations | Alex Anthopoulos[5] | ||||

| General manager | Alex Anthopoulos[4] | ||||

| Manager | Brian Snitker | ||||

| Mascot(s) | Blooper[1] | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/braves | ||||

The Atlanta Braves are an American professional baseball team based in the Atlanta metropolitan area. The Braves compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East Division. The Braves were founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1871, as the Boston Red Stockings. The club was known by various names until the franchise settled on the Boston Braves in 1912. The Braves are the oldest continuously operating professional sports franchise in North America.[6][b]

After 81 seasons and one World Series title in Boston, the club moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1953. With a roster of star players such as Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Warren Spahn, the Milwaukee Braves won the World Series in 1957. Despite the team's success, fan attendance declined. The club's owners moved the team to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1966.

The Braves did not find much success in Atlanta until 1991. From 1991 to 2005, the Braves were one of the most successful teams in baseball, winning an unprecedented 14 consecutive division titles,[7][8][9] making an MLB record eight consecutive National League Championship Series appearances, and producing one of the greatest pitching rotations in the history of baseball including Hall of Famers Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, and Tom Glavine.[10]

The Braves are one of the two remaining National League charter franchises that debuted in 1876.[11] The club has won an MLB record 23 divisional titles, 18 National League pennants, and four World Series championships. The Braves are the only Major League Baseball franchise to have won the World Series in three different home cities.[12] At the end of the 2024 season, the Braves' overall win–loss record is 11,114–10,949–154 (.504). Since moving to Atlanta in 1966, the Braves have an overall win–loss record of 4,850–4,461–8 (.521) through the end of 2024.[13]

History

[edit]Boston (1871–1952)

[edit]1871–1913

[edit]

The Cincinnati Red Stockings, formed in 1869, were the first openly all-professional baseball team but disbanded after the 1870 season.[14] Manager Harry Wright and players moved to Boston, forming the Boston Red Stockings, a charter team in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP).[15] Led by the Wright brothers, Ross Barnes, and Al Spalding, they dominated the National Association, winning four of five championships.[11] The original Boston Red Stockings team and its successors can lay claim to being the oldest continuously playing franchise in American professional sports.[6][14]

The club was known as the Boston Red Caps when they played the first National League game in 1876, winning against the Philadelphia Athletics.[16][17][18] Despite a weaker roster in the league's first year, they rebounded to secure the 1877 and 1878 pennants.[19] Managed by Frank Selee, they were a dominant force in the 19th century, winning eight pennants.[15] By 1898 the team was known as the Beaneaters and they won 102 games, with stars like Hugh Duffy, Tommy McCarthy, and "Slidin'" Billy Hamilton.[20][15]

In 1901, the American League was introduced, causing many Beaneaters players including stars Duffy and Jimmy Collins to leave for clubs of the rival league.[21] The team struggled, having only one winning season from 1900 to 1913 and losing 100 games five times. In 1907, they temporarily dropped the red color from their stockings due to infection concerns.[22] The club underwent various nickname changes until becoming the Braves before the 1912 season.[22] The president of the club, John M. Ward named the club after the owner, James Gaffney.[22] Gaffney was called one of the "braves" of New York City's political machine, Tammany Hall, which used a Native American chief as their symbol.[22][23]

1914: Miracle

[edit]In 1914, the Boston Braves experienced a remarkable turnaround in what would become one of the most memorable seasons in baseball history.[24][25] Starting with a dismal 4–18 record, the Braves found themselves in last place, trailing the league-leading New York Giants by 15 games after losing a doubleheader to the Brooklyn Robins on July 4.[26] However, the team rebounded with an incredible hot streak, going 41–12 from July 6 to September 5.[27] On August 3, Joseph Lannin the president of the Red Sox, offered Fenway Park to the Braves free of charge for the remainder of the season since their usual home, the South End Grounds, was too small.[28] On September 7 and 8, they defeated the Giants in two out of three games, propelling them into first place.[29] Despite being in last place as late as July 18, the Braves secured the pennant, becoming the only team under the old eight-team league format to achieve this after being in last place on the Fourth of July.[30][31] They were in last place as late as July 18, but were close to the pack, moving into fourth on July 21 and second place on August 12.[32]

The Braves entered the 1914 World Series led by captain and National League Most Valuable Player, Johnny Evers.[33] The Boston club were slight underdogs against Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's.[34] However, they swept the Athletics and won the world championship.[35] Inspired by their success, owner Gaffney constructed a modern park, Braves Field, which opened in August 1915 and was the largest park in the majors at the time, boasting 40,000 seats and convenient public transportation access.[36][37]

1915–1953

[edit]

From 1917 to 1933, the Boston Braves struggled. After a series of different owners, Emil Fuchs bought the team in 1923.[38] Fuchs brought his longtime friend, pitching great Christy Mathewson, as part of the syndicate that bought the club.[39] However, the death of pitching legend in 1925 left Fuchs in control.[40] Despite Fuchs' commitment to success, the team faced challenges overcoming the damage from previous years. It wasn't until 1933 and 1934, under manager Bill McKechnie, that the Braves became competitive, but it did little to help the club's finances.[41]

In an effort to boost fan attendance and finances, Fuchs orchestrated a deal with the New York Yankees to acquire Babe Ruth in 1935.[42][43] Ruth was appointed team vice president with promises of profit shares and managerial prospects.[44] Initially, Ruth seemed to provide a spark on opening day, but his declining skills became evident.[45] Ruth's inability to run and poor fielding led to internal strife, and it became clear that his titles were symbolic.[45] Ruth retired on June 1, 1935, shortly after hitting his last three home runs.[45] The Braves finished the season with a dismal 38–115 record, marking the franchise's worst season.[44]

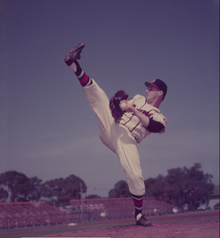

Fuchs lost control of the team in August 1935,[44] leading to a rebranding attempt as the Boston Bees, but it did little to alter the team's fortune. Construction magnate Lou Perini took over, eventually restoring the Braves' name.[46] Despite World War II causing a brief setback, the team, led by pitcher Warren Spahn, enjoyed impressive seasons in 1946 and 1947 under Perini's ownership.[44]

In 1948, the team won the pennant, behind the pitching of Spahn and Johnny Sain.[47] The remainder of the rotation was so thin that in September, Boston Post writer Gerald Hern wrote this poem about the pair:[48]

- First we'll use Spahn

- then we'll use Sain

- Then an off day

- followed by rain

- Back will come Spahn

- followed by Sain

- And followed

- we hope

- by two days of rain.

The poem received such a wide audience that the sentiment, usually now paraphrased as "Spahn and Sain and pray for rain", entered the baseball vocabulary.[49]

The 1948 World Series, which the Braves lost in six games to the Indians, turned out to be the Braves' last hurrah in Boston.[50] On March 13, 1953, Perini announced he was moving the club to Milwaukee.[51] Perini cited advent of television and the lack of enthusiasm for the Braves in Boston as the key factors in deciding to move the franchise.[51]

Milwaukee (1953–1965)

[edit]

The Milwaukee Braves' move to Wisconsin for the 1953 season was an immediate success, as they drew a National League-record 1.8 million fans and finished the season second in the league.[52] Manager Charlie Grimm was named NL Manager of the Year.[53]

Throughout the 1950s, the Braves were a National League power; driven by sluggers Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron, the team won two pennants and finished second twice between 1956 and 1959.[54] In 1957, Aaron's MVP season led the Braves to their first pennant in nine years, then a World Series victory against the formidable New York Yankees.[55] Despite a strong start in the World Series rematch the following season, the Braves ultimately lost the last three games and the World Series.[55] The 1959 season ended in a tie with the Los Angeles Dodgers, which defeated the Braves in a playoff. The ensuing years saw fluctuating success, including the Braves finishing fifth in 1963, their first time in the "second division."[54]

In 1962, team owner Louis Perini sold the Braves to a Chicago-based group led by William Bartholomay.[54] Bartholomay intended to move the team to Atlanta in 1965, but legal hurdles kept them in Milwaukee for an extra season.[54]

Atlanta (1966–present)

[edit]1966–1974

[edit]

After arriving in Atlanta in 1966, the Braves found success in 1969, with the onset of divisional play by winning the first National League West Division title.[56] In the National League Championship Series the Braves were swept by the "Miracle Mets."[57] They would post only two winning seasons between 1970 and 1981.[58] Fans in Atlanta had to be satisfied with the achievements of Hank Aaron, who by the end of the 1973 season, had hit 713 home runs, one short of Ruth's record.[59] On April 4, opening day of the next season, he hit No. 714 in Cincinnati, and on April 8, in front of his home fans and a national television audience, he finally beat Ruth's mark with a home run to left-center field off left-hander Al Downing of the Los Angeles Dodgers.[60][61] Aaron spent most of his career as a Milwaukee and Atlanta Brave before being traded to the Milwaukee Brewers on November 2, 1974.[62]

Ted Turner era

[edit]1976–1977: Ted Turner buys the team

[edit]

In 1976, the team was purchased by media magnate Ted Turner, owner of superstation WTBS, as a means to keep the team (and one of his main programming staples) in Atlanta.[58] Turner used the Braves as a major programming draw for his fledgling cable network, making the Braves the first franchise to have a nationwide audience and fan base.[58] WTBS marketed the team as "The Atlanta Braves: America's Team", a nickname that still sticks in some areas of the country, especially the South.[63][58] The financially strapped Turner used money already paid to the team for their broadcast rights as a down-payment. Turner quickly gained a reputation as a quirky, hands-on baseball owner. On May 11, 1977, Turner appointed himself manager, but because MLB passed a rule in the 1950s barring managers from holding a financial stake in their teams, Turner was ordered to relinquish that position after one game (the Braves lost 2–1 to the Pittsburgh Pirates to bring their losing streak to 17 games).[64][65]

1978–1990

[edit]The Braves didn't enjoy much success between 1978 and 1990, however, in the 1982 season, led by manager Joe Torre, the Braves secured their first divisional title since 1969.[66] The team was led by standout performances from key players like Dale Murphy, Bob Horner, Chris Chambliss, Phil Niekro, and Gene Garber.[67] The Braves were swept in the NLCS in three games by the Cardinals.[68] Murphy won the Most Valuable Player award for the National League in 1982 and 1983.[69]

1991–2005: 14 consecutive division titles

[edit]From 1991 to 2005, the Atlanta Braves enjoyed a remarkable era of success in baseball, marked by a record-setting 14 consecutive division titles, five National League pennants, and a World Series championship in 1995.[70] Bobby Cox returned as manager in 1990, leading the team's turnaround after finishing the previous season with the worst record in baseball. Notable developments included the drafting of Chipper Jones in 1990 and the hiring of general manager John Schuerholz from the Kansas City Royals.[71][72]

The Braves' remarkable journey began in 1991, known as the "Worst to First" season.[73] Overcoming a shaky start, the Braves bounced back led by young pitchers Tom Glavine and John Smoltz.[74] The team secured the NL pennant in a memorable playoff race, ultimately losing a closely contested World Series to the Minnesota Twins. The following year, the Braves won the NLCS in dramatic fashion against the Pirates but fell short in the World Series against the Toronto Blue Jays.

In 1993, the Braves strengthened their pitching staff with the addition of Cy Young Award winner Greg Maddux in free agency.[75] Despite posting a franchise-best 104 wins, they lost in the NLCS to the Philadelphia Phillies. The team moved to the Eastern Division in 1994, sparking a heated rivalry with the New York Mets.[76][77][78][79]

The player's strike cut short the 1994 season just before the division championships, but the Braves rebounded in 1995, defeating the Cleveland Indians to win the World Series.[80] With this World Series victory, the Braves became the first team in Major League Baseball to win world championships in three different cities.[81] The Braves reached the World Series in 1996 and 1999 but were defeated both times by the New York Yankees.[82][83]

In 1996, Time Warner acquired Ted Turner's Turner Broadcasting System, including the Braves.[84] Despite their continued success with a ninth consecutive division title in 2000, the Braves faced postseason disappointment with a sweep by the St. Louis Cardinals in the NLDS.[85] The team won division titles from 2002 to 2004 but experienced early exits in the NLDS each year.[86]

Liberty Media era

[edit]Liberty Media buys the team

[edit]

In December 2005, Time Warner, put the club up for sale, leading to negotiations with Liberty Media.[87][88] After over a year of talks, a deal was reached in February 2007 for Liberty Media to acquire the Braves for $450 million, a magazine publishing company, and $980 million in cash. The sale, valued at approximately $1.48 billion, was contingent on approval from 75 percent of MLB owners and Commissioner Bud Selig.[89]

Bobby Cox and Chipper Jones retire

[edit]Bobby Cox's final year as manager in 2010 saw the Braves return to the postseason for the first time since 2005.[90] The team secured the NL Wild Card but fell to the San Francisco Giants in the National League Division Series in four closely contested games, marking the conclusion of Bobby Cox's managerial career.[91] The following season the Braves suffered a historic September collapse to miss the postseason.[92] The club bounced back in 2012 and returned to the postseason in Chipper Jones' final season.[93] The Braves won 94 games in 2012, but that wasn't enough to win the NL East, so they faced the St. Louis Cardinals in the inaugural Wild Card Game.[94] Chipper Jones last game was a memorable one: the Braves lost the one game playoff 6–3, but the game would be remembered for a controversial infield fly call that helped end a Braves rally in the 8th inning.[94]

Truist Park and return to the World Series

[edit]

In 2017, the Atlanta Braves began playing at Truist Park, replacing Turner Field as their home stadium.[95] Following an MLB investigation into international signing rule violations, general manager John Coppolella resigned and faced a baseball ban.[96] Alex Anthopoulos took over as the new general manager.[97] The team's chairman, Terry McGuirk, apologized for the scandal and expressed confidence in Anthopoulos' integrity.[97] A new on field mascot named Blooper was introduced at a fan event before the 2017 season.[98] Under Anthopoulos, the Braves made the playoffs in six of his first seven seasons.[99] In 2020 the Braves reach the National League Championship Series, but ultimately lost to the Dodgers after leading 3–1.[100]

In the 2021 season, the Braves won the National League East with an 88–73 record. In the postseason, they quickly defeated the Milwaukee Brewers in the NL Division Series 3–1. The Braves again faced the Dodgers in the 2021 NLCS, and won in six games to take Atlanta's first National League pennant since 1999. The Braves advanced to the World Series.[101] They defeated the Houston Astros in six games to win their fourth World Series title.[102]

Logos and uniforms

[edit]The Braves logos have evolved over the years, featuring a Native American warrior from 1945 to 1955, followed by a laughing Native American with a mohawk and a feather from 1956 to 1965.[103][104] The modern logo, introduced in 1987, includes the cursive word "Braves" with a tomahawk below it.[105] Uniform changes occurred in 1987, with the team adopting uniforms reminiscent of their 1950s classic look.[106] For the 2023 season, the Braves had four uniform combinations, including the classic white home and gray road uniforms, a navy blue road jersey for alternate games, and two alternate uniforms for home games - a Friday night red uniform and a City Connect uniform worn on Saturdays, paying tribute to Hank Aaron.[107] The City Connect uniform features "The A" across the chest, accompanied by a cap with the "A" logo and 1974 uniform colors.[108]

World Series championships

[edit]Over the 120 years since the inception of the World Series (119 total World Series played), the Braves franchise has won a total of four World Series Championships. The Braves are the only franchise to have won a World Series in three different cities.[12]

| Season | Manager | Opponent | Series Score | Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 (Boston) | George Stallings | Philadelphia Athletics | 4–0 | 94–59 |

| 1957 (Milwaukee) | Fred Haney | New York Yankees | 4–3 | 95–59 |

| 1995 (Atlanta) | Bobby Cox | Cleveland Indians | 4–2 | 90–54 |

| 2021 (Atlanta) | Brian Snitker | Houston Astros | 4–2 | 88–73 |

| Total World Series championships: | 4 | |||

Ballparks

[edit]Truist Park

[edit]The Atlanta Braves home ballpark has been Truist Park since 2017. Truist Park is located approximately 10 miles (16 km) northwest of downtown Atlanta in the unincorporated community of Cumberland, in Cobb County, Georgia.[109] The team played its home games at Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium from 1966 to 1996, and at Turner Field from 1997 to 2016. The Braves opened Truist Park on April 14, 2017, with a four-game sweep of the San Diego Padres.[110] The park received positive reviews. Woody Studenmund of the Hardball Times called the park a "gem" saying that he was impressed with "the compact beauty of the stadium and its exciting approach to combining baseball, business and social activities."[111] J.J. Cooper of Baseball America praised the "excellent sight lines for pretty much every seat."[112]

CoolToday Park

[edit]Since 2019, the Braves have played spring training games at CoolToday Park in North Port, Florida.[113][114] The ballpark opened on March 24, 2019, with the Braves' 4–2 win over the Tampa Bay Rays.[115][116] The Braves left Champion Stadium, their previous Spring Training home near Orlando to reduce travel times and to get closer to other teams' facilities.[117] CoolToday Park also serves as the Braves' year round rehabilitation facility.[118]

Attendance

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(*) – There were no fans allowed in any MLB stadium in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major rivalries

[edit]New York Mets

[edit]Although their first major confrontation occurred when the Mets swept the Braves in the 1969 NLCS, the rivalry did not become especially heated until the 1994 season when division realignment put both the Mets and the Braves in the National League East division.[77][76][120]

The Braves faced the Mets in the 1999 National League Championship Series.[121] The Braves initially took a 3–0 series lead, seemingly on the verge of a sweep, but the Mets rallied in Game 4 and Game 5.[121] Despite the Mets' resilience, the Braves eventually won the series in Game 6 with Andruw Jones securing a dramatic walk-off walk, earning their 5th National League pennant of the decade.[121] In 2022, the Braves and Mets, both finished with 101 wins.[122] The National League East title and a first-round bye came down to a crucial three-game series at Truist Park from September 30 to October 2.[123] The Mets entered with a slight lead but faltered as the Braves swept the series.[123] Atlanta claimed the NL East division title and first-round bye, by winning the season series against the Mets.[123]

Nationwide fanbase

[edit]In addition to having strong fan support in the Metro Atlanta area and the state of Georgia, the Braves are often referred to as "America's Team" in reference to the team's games being broadcast nationally on TBS from the 1970s until 2007, giving the team a nationwide fan base.[124]

The Braves boast heavy support within the Southeastern United States particularly in states such as Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Florida.[125][126]

Tomahawk chop

[edit]

In 1991, fans of the Atlanta Braves popularized the "tomahawk chop" during games.[127] The use of foam tomahawks drew criticism from Native American groups, deeming it demeaning.[128] Despite protests, the Braves' public relations director defended it as a "proud expression of unification and family."[128] The controversy resurfaced in 2019 when Cherokee Nation member and St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Ryan Helsley found the chop insulting, prompting the Braves to modify their in-game experience.[129] During the off-season, discussions ensued with Native American representatives, and amid pressure in 2020 to change their name, the Braves announced ongoing talks about the chop but insisted the team name would remain unchanged.[130]

The debate over the tomahawk chop continued into 2021.[131] While some Native American leaders, like Richard Sneed, the Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, expressed personal indifference or tolerance, acknowledging it as an acknowledgment of Native American strength, others vehemently opposed it.[132][133] Sneed emphasized larger issues facing Native American communities and questioned the focus on the chop.[134] The Eastern Cherokee Band of Indians and the Braves initiated efforts to incorporate Cherokee language and culture into the team's activities, stadium, and merchandise, aiming for greater cultural sensitivity despite differing opinions within the Native American community.[135]

Achievements

[edit]Awards

[edit]Team records

[edit]Retired numbers

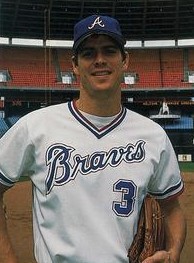

[edit]The Braves have retired eleven numbers in the history of the franchise, including most recently Andruw Jones' number 25 in 2023, Chipper Jones' number 10 in 2013, John Smoltz's number 29 in 2012, Bobby Cox's number 6 in 2011, Tom Glavine's number 47 in 2010, and Greg Maddux's number 31 in 2009. Additionally, Hank Aaron's 44, Dale Murphy's 3, Phil Niekro's 35, Eddie Mathews' 41, Warren Spahn's 21 and Jackie Robinson's 42, which is retired for all of baseball with the exception of Jackie Robinson Day, have also been retired.[136] Six of the eleven numbers (Cox, Jones, Jones, Smoltz, Maddux and Glavine) were on the Braves at the same time.[137] Of the eleven Braves whose numbers have been retired, all who are eligible for the National Baseball Hall of Fame have been elected with the exceptions of Dale Murphy and Andruw Jones.[138] The color and design of the retired numbers on commemorative markers and other in-stadium signage reflect the primary uniform design at the time the player was on the team.[139]

|

Baseball Hall of Famers

[edit]

| Atlanta Braves Hall of Famers | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Braves Hall of Fame

[edit]

| Year | Year inducted |

|---|---|

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as a Brave |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Braves Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Name | Position(s) | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 21 | Warren Spahn† | P | 1942, 1946–1964 |

| 35 | Phil Niekro† | P | 1964–1983, 1987 | |

| 41 | Eddie Mathews† | 3B Manager |

1952–1966 1972–1974 | |

| 44 | Hank Aaron† | RF | 1954–1974 | |

| 2000 | — | Ted Turner | Owner/President | 1976–1996 |

| 3 | Dale Murphy | OF | 1976–1990 | |

| 2001 | 32 | Ernie Johnson Sr. | P Broadcaster |

1950, 1952–1958 1962–1999 |

| 2002 | 28, 33 | Johnny Sain | P Coach |

1942, 1946–1951 1977, 1985–1986 |

| — | Bill Bartholomay | Owner/President | 1962–1976 | |

| 2003 | 1, 23 | Del Crandall | C | 1949–1963 |

| 2004 | — | Pete Van Wieren | Broadcaster | 1976–2008 |

| — | Kid Nichols† | P | 1890–1901 | |

| 1 | Tommy Holmes | OF Manager |

1942–1951 1951–1952 | |

| — | Skip Caray | Broadcaster | 1976–2008 | |

| 2005 | — | Paul Snyder | Executive | 1973–2007 |

| — | Herman Long | SS | 1890–1902 | |

| 2006 | — | Bill Lucas | GM | 1976–1979 |

| 11, 48 | Ralph Garr | OF | 1968–1975 | |

| 2007 | 23 | David Justice | OF | 1989–1996 |

| 2009 | 31 | Greg Maddux[154] | P | 1993–2003 |

| 2010 | 47 | Tom Glavine†[155] | P | 1987–2002, 2008 |

| 2011 | 6 | Bobby Cox†[156][157][158] | Manager | 1978–1981, 1990–2010 |

| 2012 | 29 | John Smoltz†[159] | P | 1988–1999, 2001–2008 |

| 2013 | 10 | Chipper Jones†[160] | 3B/LF | 1993–2012 |

| 2014 | 8 | Javy López | C | 1992–2003 |

| 1 | Rabbit Maranville† | SS/2B | 1912–1920 1929–1933, 1935 | |

| — | Dave Pursley | Trainer | 1961–2002 | |

| 2015 | — | Don Sutton | Broadcaster | 1989–2006, 2009–2020 |

| 2016 | 25 | Andruw Jones | CF | 1996–2007 |

| — | John Schuerholz | Executive | 1990–2016 | |

| 2018 | 15 | Tim Hudson | P | 2005–2013 |

| — | Joe Simpson | Broadcaster | 1992–present | |

| 2019 | — | Hugh Duffy | OF | 1892–1900 |

| 5, 9 | Terry Pendleton | 3B Coach |

1991–1994, 1996 2002–2017 | |

| 2022[161] | 9 | Joe Adcock | 1B/OF | 1953–1962 |

| 54 | Leo Mazzone | Coach | 1990–2005 | |

| 9, 15 | Joe Torre | C/1B/3B Manager |

1960–1968 1982–1984 | |

| 2023[162] | 25, 43, 77 | Rico Carty | LF | 1963–1972 |

| — | Fred Tenney | 1B | 1894–1907, 1911 | |

Roster

[edit]| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers

Infielders

Outfielders

Designated hitters |

|

Manager Coaches

39 active, 0 inactive, 0 non-roster invitees

| |||

Minor league affiliates

[edit]The Atlanta Braves farm system consists of six minor league affiliates.[163]

| Class | Team | League | Location | Ballpark | Affiliated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triple-A | Gwinnett Stripers | International League | Lawrenceville, Georgia | Coolray Field | 2009 |

| Double-A | Columbus Clingstones | Southern League | Columbus, Georgia | Synovus Park | 2025 |

| High-A | Rome Emperors | South Atlantic League | Rome, Georgia | AdventHealth Stadium | 2003 |

| Single-A | Augusta GreenJackets | Carolina League | North Augusta, South Carolina | SRP Park | 2021 |

| Rookie | FCL Braves | Florida Complex League | North Port, Florida | CoolToday Park | 1976 |

| DSL Braves | Dominican Summer League | Boca Chica, Santo Domingo | Atlanta Braves Complex | 2022 |

Radio and television

[edit]The Braves regional games are exclusively broadcast on Bally Sports Southeast. Brandon Gaudin is the play-by-play announcer for Bally Sports Southeast.[164] Gaudin is joined in the booth by lead analyst C.J. Nitkowski.[165] Jeff Francoeur and Tom Glavine will also join the broadcast for a few games during the season.[166] Peter Moylan, Nick Green, and John Smoltz also appear in the booth for select games as in-game analysts.[167][168]

The radio broadcast team is led by the tandem of play-by-play announcer Ben Ingram and analyst Joe Simpson. Braves games are broadcast across Georgia and seven other states on at least 172 radio affiliates, including flagship station 680 The Fan in Atlanta and stations as far away as Richmond, Virginia; Louisville, Kentucky; and the US Virgin Islands. The games are carried on at least 82 radio stations in Georgia.[169]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The team's official colors are navy blue and scarlet red, according to the team's mascot (BLOOPER)'s official website.[1]

- ^ The Cubs are a full season older as they were originally founded as the Chicago White Stockings in 1870. The White Stockings did not field a team in 1871 or 1872, however, due to the Great Chicago Fire. The Braves, therefore, have played more consecutive seasons.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Meet BLOOPER". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Major League Baseball and the Atlanta Braves unveil the official logo of the 2021 All-Star Game". Braves.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. September 24, 2020. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

The official logo of the 2021 MLB All-Star Game highlights Atlanta's spectacular new ballpark. From the shape of the wall medallion to the entry truss, baseball fans are welcomed into the event with its modern amenities surrounded by Southern hospitality. From the warmth of the brick to the steel of the truss, the logo is punctuated by Atlanta's colors of navy and red and is signed by the signature script of the Braves' franchise.

- ^ "Stockholders vote to split off Braves from Liberty Media". ajc.com

- ^ Bowman, Mark (November 12, 2017). "Braves introduce Anthopoulos as new GM, VP". MLB.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Burns, Gabriel (February 17, 2020). "Braves extend contracts of Anthopoulos, Snitker". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "Story of the Braves". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "BASEBALL: NATIONAL LEAGUE ROUNDUP; Braves Clinch Division For 14th Straight Time". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 28, 2005. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (September 13, 2006). "Braves have set lofty benchmark". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Braves' 14 straight division titles should be cheered". MLB.com. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Powell, Michael (January 4, 2019). "Deep in Winter, Let's Discuss the Stifling of Starting Pitchers". New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Neil W. (May 18, 2004). The League That Lasted: 1876 and the Founding of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786417551.

- ^ a b Walker, Ben (October 29, 1995). "Champions At Last". Indiana Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Sewell, Dan (February 11, 2019). "Season-long tribute planned to pioneering 1869 Red Stockings". The Washington Times. Associated Press. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c Souder, Mark (December 19, 2019). "How Bostonians Became the Beaneaters". The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s. Society for American Baseball Research. ISBN 978-1970159196.

- ^ Events of Saturday, April 22, 1876 Archived July 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrosheet. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Noble, Marty (September 23, 2011). "MLB carries on strong, 200,000 games later: Look what they started on a ballfield in Philadelphia in 1876". MLB.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

[B]aseball is about to celebrate its 200,000th game — [in the division series on] Saturday [October 1, 2011] ....

- ^ Thorn, John (May 4, 2015). "Why Is the National Association Not a Major League … and Other Records Issues". OurGame.MLBlogs.com. Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

The National Association, 1871–1875, shall not be considered as a 'major league' due to its erratic schedule and procedures, but it will continue to be recognized as the first professional baseball league.

- ^ "Sporting Matters". Boston Globe. October 7, 1878. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Murnane, T.H. (October 12, 1898). "Boston Again Champions". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Boston Team Completed". Boston Evening Transcript. March 6, 1901. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Murnane, T.H. (December 21, 1911). "Ward Wants His Team to be Called the "Boston Braves"". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Kaese, Harold The Boston Braves, Northeastern University Press, 1948.

- ^ Overfield, Joseph M. (May 1961). "How Losing an Exhibition Sparked Miracle Braves". Baseball Digest. 20 (4). Evanston: Lakeside Publishing Company: 83–85. ISSN 0005-609X.

- ^ Vass, George (September 2001). "Down To The Wire; Six Greatest Stretch Runs For The Pennant". Baseball Digest. 60 (9). Evanston: Lakeside Publishing Company: 26–35. ISSN 0005-609X.

- ^ O'Leary, J.C. (July 5, 1914). "Chances Thrown Away by Braves' Misplays". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "1914 Boston Braves Schedule by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Murnane, T.H. (August 4, 1914). "Fenway Park for Braves". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ O'Leary, J.C. (September 9, 1914). "Braves on Top Again". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "1914 New York Giants Schedule by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Nowlin, Bill (February 1, 2014). The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston's Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions. Society for American Baseball Research. p. 380. ISBN 978-1933599694.

- ^ Cohen, Neft, Johnson and Deutsch, The World Series, The Dial Press, 1976.

- ^ "Johnny Evers and Eddie Collins Chalmers Trophy Winners for 1914". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 4, 1914. p. 29. Retrieved February 9, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

Johnny Evers, captain and second baseman of the champion Boston Braves, is winner of the Chalmers Trophy in the National League of 1914, with 50 out of a possible 64 points.

- ^ "Million and a Half in Wagers on World Series". New Castle News. October 9, 1914. p. 15. Retrieved February 9, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

The general betting today, however was 5 to 4 on the Athletics. Last week the odds were around 7 to 4 on the Athletics, while two or three weeks ago when it looked certain that the Braves would win the pennant, the Athletic backers offered 2 to 1 and 3 to 1 against the Braves

- ^ O'Leary, J.C. (October 13, 1914). "Braves Win 3-1". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Murnane, T.H. (December 5, 1914). "Boston Braves to Move to Allston". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ O'Leary, J.C. (August 18, 1914). "Braves Field Opening Today". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Craig, William J. (November 20, 2012). A History of the Boston Braves: A Time Gone By. The History Press. ISBN 978-1609498573.

- ^ Fuchs, Robert S.; Soini, Wayne (April 15, 1998). Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1923-1935. McFarland. p. 24. ISBN 978-0786404827.

- ^ "Judge Fuchs is Elected President of Braves to Fill Mathewson Vacancy". Boston Herald. October 22, 1925. p. 13.

- ^ Fuchs, Robert S.; Soini, Wayne (April 15, 1998). Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1923-1935. McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 978-0786404827.

- ^ Cameron, Stuart (February 27, 1935). "Acquisition of Bate Ruth May Pull the Braves Out of the 'Red'". Brooklyn Citizen. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (June 2, 2015). "The Disappointing Reason Babe Ruth Left Baseball". Time. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. New York: Fireside. ISBN 978-0-7432-8491-2.

- ^ a b c Fuchs, Robert S.; Soini, Wayne (April 15, 1998). Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1923-1935. McFarland. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0786404827.

- ^ King, Bill (April 30, 1941). "It's Braves Again as New Owners Stamp Out 'Bees'". The Post-Crescent. Associated Press. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Hand, Jack (October 6, 1948). "Indians 5 to 1 Favorites to Win the Series". Moberly Monitor-Index and Moberly Evening Democrat. Associated Press. p. 9. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Red (January 29, 1973). "Spahnie and Howie". The Berkshire Eagle. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Bellamy, Clayton (November 25, 2003). "Hall-of-Famer Spahn dead at 82". Delphos Herald Newspaper. Associated Press. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Frost, Jake (October 12, 1948). "Braves Unable to Beat Luck, Says Sothwort". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. U.P. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Hand, Jack (March 19, 1953). "More Territory to be Drafted O'Malley Says". Rhinelander Daily News. Associated Press. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Milwaukee Braves' Attendance Boosts Saved National". The Commercial-Mail. U.P. September 28, 1953. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Charlie Grimm is National League Manager of the Year". Rhinelander Daily News. Associated Press. October 22, 1953. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Wisnia, Saul (March 28, 2014). "From Yawkey to Milwaukee: Lou Perini Makes his Move". Thar's Joy in Braveland: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves. Society for American Baseball Research. pp. 5–11. ISBN 978-1933599717.

- ^ a b Johnson, William (March 28, 2014). "Henry 'Hank' Aaron". Thar's Joy in Braveland: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves. Society for American Baseball Research. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-1933599717.

- ^ "Braves Capture National League West Division Title". Panama City News-Herald. Associated Press. October 1, 1969. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "It's Mets and Orioles In Fall Classic". Warren Times-Mirror and Observer. Associated Press. October 7, 1969. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Trutor, Clayton (February 1, 2022). Loserville. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1496225047.

- ^ "Aaron Looks to '74". St. Lucie News Tribune. United Press International. October 1, 1973. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Season's First Hit Gets Aaron Tie With Ruth". The Daily Courier. United Press International. April 5, 1974. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Moffit, David (April 5, 1974). "Big Homer Record Chase Finally Ends for Aaron". The Daily Courier. United Press International. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Richmond, Milton (November 3, 1974). "Brewers Get Aaron". The Daily Courier. United Press International. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (August 9, 1982), America's Team II, Sports Illustrated, archived from the original on June 3, 2011

- ^ "Turner Takes Over for Bristol". Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph. Associated Press. May 12, 1977. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Kuhn Rejects Turner". Times Recorder. Associated Press. May 14, 1977. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Embry, Mike (November 9, 1983). "Braves Back Into Playoffs". Daily American Republic. Associated Press. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Blue Jays' Cox Leaves Land of the Freeze for the Home of the Braves". Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1985. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "Cards, Brewers Advance to World Series". Indiana Gazette. Associated Press. October 11, 1982. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Murphy Repeats as MVP". Daily American Republic. Associated Press. November 9, 1983. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Ringolsby, Tracy (June 19, 2017). "Braves' 14 straight division titles should be cheered". MLB. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Bowman, Mark. "Chipper a wise choice for Braves in 1990 Draft". MLB.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (June 23, 2020). "14 division titles: Schuerholz is Braves' best GM". MLB.com. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Walburn, Lee (March 18, 2015). "Unbelievable! The Braves 1991 worst to first season". Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Burns, Gabriel (June 25, 2020). "How Leo Mazzone became baseball's best pitching coach". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Maske, Mark (December 10, 1992). "Maddux To Braves For $28 Million". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Bodley, Hal (September 16, 1993). "Pirates OK new realignment". USA Today. p. 1C.

The Pirates will switch from the East next season. They opposed the move last week when realignment was approved, but agreed to allow Atlanta to move to the East.

- ^ a b Olson, Lisa (July 8, 2003). "Crazy scene at Shea takes luster off Mets-Braves rivalry". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ The subway series: the Yankees, the Mets and a season to remember. St. Louis, Mo.: The Sporting News. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89204-659-1.

- ^ Chass, Murray (October 17, 2000). "From Wild Card to World Series". The New York Times.

- ^ Makse, Mark (October 29, 1995). "Atlanta, at last; Braves Win World Series". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves 1995 summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "1996 Atlanta Braves season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ "1999 Atlanta Braves summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ Rice, Marc (October 11, 1996). "Done Deal". Ellwood City Ledger. Associated Press. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Saladino, Tom (October 8, 2000). "Braves Swept Out of Playoffs". South Florida Sun Sentinel. Associated Press. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ "Astros Deck Braves to get to NLCS". The Iola Register. Associated Press. October 12, 2004. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Pelline, Jeff (September 23, 1995). "Time Warner Closes Deal for Turner". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (December 14, 2005). "Time Warner considers Braves sale". CNNMoney.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Burke, Monte (May 5, 2008). "Braves' New World – Forbes Magazine". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Odum, Charles (October 4, 2010). "Cox not finished yet after Braves win NL wild card". San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "San Francisco Giants bounce Atlanta Braves from the playoffs in manager Bobby Cox's final game". Pioneer Press. Associated Press. October 11, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ O Brien, David (October 1, 2012). "Chronology of Braves' collapse". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Chipper Jones plan to retire". ESPN.com. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Blinder, Alan; Waldstein, David (October 3, 2019). "The Braves, the Cardinals and an Infamous Infield Fly: An Oral History". New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Odum, Charles (April 14, 2017). "Braves greats help celebrate opening of new SunTrust Park". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "Braves GM John Coppolella Resigns Amid MLB Investigation Over International Signings". Sports Illustrated. October 2, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "Braves hire former Dodgers, Blue Jays exec Alex Anthopoulos as GM". ESPN. November 13, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ "Fans react to Blooper, the new Braves mascot". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ O'Brien, David; Weese, Lukas (January 12, 2024). "Braves extend GM Alex Anthopoulos on multiyear deal". The Athletic. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Waldstein, David (October 18, 2020). "Dodgers Rally to Win N.L.C.S. and Reach 3rd World Series in 4 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (November 2, 2021). "Atlanta Topples Dodgers To Reach First World Series Since 1999". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Waldstein, David (November 11, 2021). "Atlanta Overcomes Decades of Frustration to Win World Series". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Boston Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Milwaukee Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Braves' New Look". The Herald-Sun. Associated Press. January 17, 1987. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Braves Uniforms". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Toscano, Justin (March 27, 2023). "'Keep Swinging #44′: Braves unveil Hank Aaron tribute uniforms". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (November 11, 2013). "Braves leaving Turner Field for Cobb County". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ Cunningham, Michael (April 15, 2017). "Braves' Inciarte homers again on night of firsts at new park". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Studenmund, Woody (May 3, 2017). "Atlanta's SunTrust Park: The First of a New Generation?". Hardball Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ Cooper, J.J. (May 2, 2017). "Braves' New Ballpark Has All Modern Touches, But It's What Surrounds SunTrust Park That Makes It Stand Out". Baseball America. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (January 17, 2017). "Braves eye new Spring Training complex in North Port". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Murdock, Zack (January 17, 2017). "Atlanta Braves pick Sarasota County for spring training". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Rodriguez, Nicole (March 1, 2019). "Atlanta Braves stadium in North Port nearing completion". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Tucker, Tim (March 24, 2019). "Braves' Gausman takes 'another step' toward 'being ready'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Tucker, Tim (February 27, 2017). "Braves agree on key terms for new spring home". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Rodriguez, Nicole (November 9, 2018). "Braves spring training complex will be a 'game changer' for North Port, analyst says". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves Attendance". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Chass, Murray (September 16, 1993). "Pirates Relent on New Alignment". The New York Times. p. B14. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c Walker, Ben (October 20, 1999). "Braves Survive Mets in 11, 10-9". Salina Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Crizer, Zach (October 10, 2022). "101 and done: How will the 2022 Mets' soaring summer and crushing wild-card exit be remembered?". Yahoo Sports. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c Hoffman, Benjamin (October 4, 2022). "Wild Cards: The Mets Are Officially Eliminated in the N.L. East". New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "The Atlanta Braves are known as America's Team, but why?". WXIA-TV. October 29, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ "Where do MLB Fans Live? Mapping Baseball Fandom Across the U.S." SeatGeek.com. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Tim (October 22, 2021). "From near and far, Braves Country rooting for a World Series". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Shultz, Jeff (July 17, 1991). "Tomahawks? Scalpers? Fans whoop it up". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Anderson, Dave (October 13, 1991). "The Braves' Tomahawk Phenomenon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Johnny (October 13, 2019). "Chiefs of Georgia native tribes call tomahawk chop 'inappropriate'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Rosenthal, Ken (July 7, 2020). "The Braves are discussing their use of the Tomahawk Chop, but not their name". The Athletic. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ Burns, Gabe (April 9, 2021). "Braves use 'tomahawk chop' during home opener". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Spencer, Sarah (July 10, 2020). "Braves' name, chop are complex and personal issues for Native Americans". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Streeter, Kurt (October 29, 2021). "M.L.B. Commissioner Can't Hear Native Voices Over Atlanta's Chop". The New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Stephanie Apstein (October 28, 2021). "Why Does MLB Still Allow Synchronized, Team-Sanctioned Racism in Atlanta?". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Joseph (August 28, 2020). "Braves work with tribe to address cultural concerns". Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Araton, Harvey (April 14, 2010). "Yankees' Mariano Rivera Is the Last No. 42". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "1996 Atlanta Braves Roster | Baseball Almanac". www.baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (April 3, 2023). "Braves to retire No. 25 in honor of Andruw on Sept. 9". MLB.com.

- ^ Pahigian, Josh; Kevin O'Connell (2004). The Ultimate Baseball Road-trip: A Fan's Guide to Major League Stadiums. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-159-1.

- ^ "Mathews, Eddie". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Aaron, Hank". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Cepeda, Orlando". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Cox, Bobby". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Glavine, Tom". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Jones, Chipper". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Maddux, Greg". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "McGriff, Fred". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Perry, Gaylord". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Schuerholz, John". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Simmons, Ted". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Smoltz, John". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Sutter, Bruce". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Torre, Joe". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Rogers, Carroll (July 17, 2009). "Maddux enters Braves' Hall of Fame". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "bio". May 10, 2010.

- ^ "Bobby Cox honored in Atlanta (video)". Atlanta Braves official website. August 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (August 12, 2011). "Cox humbled by entrance into Braves' Hall". MLB.com. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ "Bobby Cox's No. 6 retired by Braves". FOXNews.com. Associated Press. August 12, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (June 8, 2012). "Braves give Smoltz team's highest honor". Atlanta Braves official website. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- ^ Goldman, David. "Braves retire Chipper Jones' No. 10 jersey". AP. SI.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves to host Alumni Weekend with Braves Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Home Run Derby at Truist Park July 29–31". MLB.com.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (August 18, 2023). "Carty, Tenney to enter Braves Hall of Fame". Major League Baseball. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Toscano, Justin (February 16, 2023). "Brandon Gaudin new Braves play-by-play voice on Bally Sports South and Southeast". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Toscano, Justin (December 18, 2022). "Bally Sports South adds Alpharetta resident C.J. Nitkowski to replace Jeff Francoeur on Braves broadcasts". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Toscano, Justin (March 15, 2023). "Hall of Famer Tom Glavine set to return to Braves broadcasts in 2023". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ "Bally Sports Announces 2023 Atlanta Braves Broadcast Team". Bally Sports Southeast. March 20, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Toscano, Justin (August 7, 2023). "John Smoltz to join Braves broadcasts for two series". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Tucker, Tim (April 1, 2022). "Braves' radio broadcasters lineup set for 2022". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Wilkinson, Jack (2007). Game of my Life: Atlanta Braves. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-59670-099-4.

- Green, Ron Jr. (2008). 101 Reasons to Love the Braves. Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 978-1-58479-670-1.

External links

[edit]- Atlanta Braves official website

- Team index page at Baseball Reference

- Milwaukee Braves informational website

- Sports Illustrated Atlanta Braves Page

- ESPN Atlanta Braves Page

- History of the Boston Braves on MassHistory.com

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | World Series champions Boston Braves 1914 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Milwaukee Braves 1957 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Atlanta Braves 1995 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Atlanta Braves 2021 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Red Caps 1877–1878 |

Succeeded by Providence Grays

1879 |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1883 |

Succeeded by Providence Grays

1884 |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1891–1893 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1897–1898 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by New York Giants

1913 |

National League champions Boston Braves 1914 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Brooklyn Dodgers

1947 |

National League champions Boston Braves 1948 |

Succeeded by Brooklyn Dodgers

1949 |

| Preceded by Brooklyn Dodgers

1956 |

National League champions Milwaukee Braves 1957–1958 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1991–1992 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1995–1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1999 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 2021 |

Succeeded by |

- Atlanta Braves

- Major League Baseball teams

- Grapefruit League

- Liberty Media subsidiaries

- Companies listed on the Nasdaq

- Companies traded over-the-counter in the United States

- 19th century in Boston

- Baseball teams in Boston

- Baseball teams established in 1876

- 1876 establishments in Massachusetts

- Former Time Warner subsidiaries

- Baseball teams in Georgia (U.S. state)