Milam Park

| Milam Park | |

|---|---|

The Benjamin Milam Statue at Milam Park | |

| Location | 500 W. Houston St. San Antonio, Texas, United States |

| Coordinates | 29°25′34″N 98°29′58″W / 29.426049°N 98.4994716°W |

| Area | 3.6 acres (1.5 ha) |

| Created | January 7, 1884 |

| Operated by | City of San Antonio |

| Website | Official website |

Milam Park, formerly Milam Square, is an urban park located in downtown San Antonio, Texas, United States. Originally used as a burial ground, the park was established in 1884. It is named after Benjamin Milam, whose remains are interred under a monument on the west end of the park.

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]The modern history of the site dates back to 1848, when it was designated for use as a city cemetery.[1] It adjoined a Catholic cemetery called El Campo Santo, over which the Santa Rosa Hospital now sits. However, the population quickly outgrew the burial ground. In the 1860s, the cemetery closed and the city planned to convert it into a public park. Most families moved their loved ones' burials elsewhere.[1] Although no remains (besides Benjamin Milam's) are known to have been uncovered inside the park since its opening, evidence of burials have been recovered from excavations and streetworks in the immediate vicinity.[2] In 1883, the city officially established Milam Square, dedicating it on January 7, 1884.[3] By 1885, sidewalks had been paved over, greenery planted, and the park was fully opened to the public.[1] A bandstand was erected about 1903 but was torn down in 1908 for unknown reasons.[4] In 1936, a memorial statue to Ben Milam was placed over his gravesite in the center of the park.

Redevelopment

[edit]Milam Park underwent a large redevelopment in the 1970s, undertaken in tandem with rejuvenation of the Market Square to the south of the park. $374,210 in funding was awarded by the San Antonio Development Agency for the project in 1975. Landschape architect Jim Keeter was hired to design the park, while Bill Shannon, Inc. was contracted to carry out the works.[5] The Friends of Milam Park was established as a branch of the San Antonio Parks Foundation by Drs. Carlos Orozco and Hugo Castaneda to oversee and fundraise for the works. Under this organization, several new amenities were added.[1]

These works coincided with two heated controversies over the works. The first major issue was raised by locals over the site originally being a religious burial ground, the possibility that works could disturb any remaining graves, and its continued use as a park.[6] The Texas Hispanic-American History Foundation asked that the area be commemorated as a Catholic cemetery and the statue of Ben Milam be removed. The San Antonio Development Agency, in charge of the renovations, declined these requests.[7] The second issue was with 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) spine walls that had been erected in the park during construction. Locals complained the walls were both a public safety hazard and visually displeasing.[8]

Features

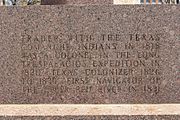

[edit]The two main features of Milam Park are the Jalisco Pavilion, a gazebo at the center of the park; and the Ben Milam Statue, a monument to Texas Revolutionary Benjamin Milam. The park also features walking and jogging trails, exercise equipment, a playground, and games tables.[9] Just north of the Jalisco Pavilion is a 2009 monument to Emma Tenayuca, who frequented the park as a child.[10] In the northwest corner near the Ben Milam Statue is another historical marker honoring Henry Karnes, another Texas Revolutionary.[11]

Jalisco Pavilion

[edit]The Jalisco Pavilion sits at the park's center. It was designed by Jalisco architect Salvador de Alba Martin as park of the park's renovations in the 1990s. It is 26 feet (7.9 m) wide with a cantera base and a copper domed roof, supported by cast iron railings and columns. The gazebo is sometimes used for weddings.[9]

Ben Milam Statue

[edit]Ben Milam Statue | |

| Built | 1938 |

|---|---|

| Sculptor | Bonnie MacLeary |

| MPS | Monuments and Buildings of the Texas Centennial |

| NRHP reference No. | 100005535[3] |

| Added to NRHP | February 6, 2020 |

Benjamin Rush Milam was a Texas Revolutionary who was killed during the Siege of Béxar in 1835. After the establishment of the burial ground, his remains—as well as those of other Texas Revolutionaries—were moved there on December 7, 1848, but were unmarked. A movement led by Valentine Overton King in 1873 uncovered the location of the gravesite and had a marker placed there.[3] In 1883, after the cemetery had closed, the city council briefly considered reinterring Milam elsewhere but ultimately decided his remains would stay in the newly established Milam Park.[1]

In the 1930s, the centennial of Texan independence was being celebrated statewide, and with it several monuments to Texan history and its figures were erected. This surge of interest was largely driven by historical and heritage organizations, such as the De Zavala chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. De Zavala had been trying since the 1890s to have a larger monument installed on Milam's gravesite but had previously been unsuccessful in raising the proper funding. Finally, in 1936, the U.S. Texas Centennial Commission agreed to allocate the funds. Sculptor Bonnie MacLeary, whose grandfather was Valentine Overton King, was hired to create the 13-foot-tall (4.0 m) bronze cast statue of Milam, to be placed over Milam's gravesite on the west side of the park. Architect Donald S. Nelson was consulted for the design of the granite base. The sculpture was unveiled in a public ceremony on September 8, 1938.[3]

During works in 1976, amongst the chaos of the construction works, the Ben Milam Statue was moved to a corner of the park, removing any surface marking indicating the exact location of Milam's burial. In 1993, Milam's remains were rediscovered near the center of the park, underneath where the gazebo now sits.[12] The remains were exhumed and sent to the University of Texas at San Antonio for archaeological study. They were subsequently reinterred the following year at the base of the Ben Milam Statue, underneath a raised horizontal granite slab.[3]

Several sidewalks converge at a small plaza, with the monument itself in the center. The statue of Milam, posed with a flintlock rifle raised above his head, sits atop an octagonal granite pillar on a square base, facing east towards downtown and the Alamo. The monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 16, 2020.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Milam Park History". City of San Antonio. City of San Antonio. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Sauers, Camille (August 20, 2021). "A brief and controversial history of former San Antonio cemetery Milam Park". My San Antonio. Hearst Newspapers. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "NRHP Nomination Form: Ben Milam Statue" (PDF). Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Want Place for the Speaker". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. April 7, 1908. p. 4. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Park contract awarded". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. October 8, 1975. p. 16-A. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Delgado, Gloria (December 14, 1975). "Navarro descendent fights for S.A.'s first cemetery". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. p. 2-N. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weser, Deborah (September 13, 1972). "Historic Debate Again Is Looming". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. p. 2-A. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weser, Deborah (July 24, 1976). "Problem of wall becoming costly". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. p. 3-A. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Milam Park". City of San Antonio. City of San Antonio. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Emma Tenayuca". Historical Marker Database. Historical Marker Database. March 2, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Colonel Henry Wax Karnes". Historical Marker Database. Historical Marker Database. August 19, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Grave of Texas war hero Milam believed found in San Antonio". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. Associated Press. January 17, 1993. p. B8. Retrieved December 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.