Middle East

| |

| Area | 7,207,575 km2 (2,782,860 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | |

| Countries | UN members (16) UN observer (1) |

| Dependencies | |

| Languages | 60 languages

|

| Time zones | UTC+2 to UTC+4 |

| Largest cities | |

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language)[note 1] is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western European nations in the early 20th century as a replacement of the term Near East (both were in contrast to the Far East). The term "Middle East" has led to some confusion over its changing definitions.[2] Since the late 20th century, it has been criticized as being too Eurocentric.[3] The region includes the vast majority of the territories included in the closely associated definition of West Asia, but without the South Caucasus. It also includes all of Egypt (not just the Sinai) and all of Turkey (including East Thrace).

Most Middle Eastern countries (13 out of 18) are part of the Arab world. The most populous countries in the region are Egypt, Turkey, and Iran, while Saudi Arabia is the largest Middle Eastern country by area. The history of the Middle East dates back to ancient times, and it was long considered the "cradle of civilization". The geopolitical importance of the region has been recognized and competed for during millennia.[4][5][6] The Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, have their origins in the Middle East.[7] Arabs constitute the main ethnic group in the region,[8] followed by Turks, Persians, Kurds, Azeris, Copts, Jews, Assyrians, Iraqi Turkmen, Yazidis, and Greek Cypriots.

The Middle East generally has a hot, arid climate, especially in the Arabian and Egyptian regions. Several major rivers provide irrigation to support agriculture in limited areas here, such as the Nile Delta in Egypt, the Tigris and Euphrates watersheds of Mesopotamia, and the basin of the Jordan River that spans most of the Levant. These regions are collectively known as the Fertile Crescent, and comprise the core of what historians had long referred to as the cradle of civilization (multiple regions of the world have since been classified as also having developed independent, original civilizations).

Conversely, the Levantine coast and most of Turkey have relatively temperate climates typical of the Mediterranean, with dry summers and cool, wet winters. Most of the countries that border the Persian Gulf have vast reserves of petroleum. Monarchs of the Arabian Peninsula in particular have benefitted economically from petroleum exports. Because of the arid climate and dependence on the fossil fuel industry, the Middle East is both a major contributor to climate change and a region that is expected to be severely adversely affected by it.

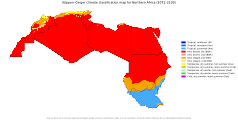

Other concepts of the region exist, including the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which includes states of the Maghreb and the Sudan. The term the "Greater Middle East" also includes parts of East Africa, Mauritania, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and sometimes the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

Terminology

The term "Middle East" may have originated in the 1850s in the British India Office.[9] However, it became more widely known when United States naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan used the term in 1902[10] to "designate the area between Arabia and India".[11][12]

During this time the British and Russian empires were vying for influence in Central Asia, a rivalry that would become known as the Great Game. Mahan realized not only the strategic importance of the region, but also of its center, the Persian Gulf.[13][14] He labeled the area surrounding the Persian Gulf as the Middle East. He said that, beyond Egypt's Suez Canal, the Gulf was the most important passage for Britain to control in order to keep the Russians from advancing towards British India.[15] Mahan first used the term in his article "The Persian Gulf and International Relations", published in September 1902 in the National Review, a British journal.

The Middle East, if I may adopt a term which I have not seen, will some day need its Malta, as well as its Gibraltar; it does not follow that either will be in the Persian Gulf. Naval force has the quality of mobility which carries with it the privilege of temporary absences; but it needs to find on every scene of operation established bases of refit, of supply, and in case of disaster, of security. The British Navy should have the facility to concentrate in force if occasion arise, about Aden, India, and the Persian Gulf.[16]

Mahan's article was reprinted in The Times and followed in October by a 20-article series entitled "The Middle Eastern Question", written by Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol. During this series, Sir Ignatius expanded the definition of Middle East to include "those regions of Asia which extend to the borders of India or command the approaches to India."[17] After the series ended in 1903, The Times removed quotation marks from subsequent uses of the term.[18]

Until World War II, it was customary to refer to areas centered around Turkey and the eastern shore of the Mediterranean as the "Near East", while the "Far East" centered on China, India and Japan.[19]

The Middle East was then defined as the area from Mesopotamia to Burma, namely, the area between the Near East and the Far East.[20][21] In the late 1930s, the British established the Middle East Command, which was based in Cairo, for its military forces in the region. After that time, the term "Middle East" gained broader usage in Europe and the United States. Following World War II, for example, the Middle East Institute was founded in Washington, D.C. in 1946.[22]

The corresponding adjective is Middle Eastern and the derived noun is Middle Easterner.

While non-Eurocentric terms such as "Southwest Asia" or "Swasia" have been sparsely used, the classificiation of the African country, Egypt, among those counted in the Middle East challenges the usefulness of using such terms.[23]

Usage and criticism

The description Middle has also led to some confusion over changing definitions. Before the First World War, "Near East" was used in English to refer to the Balkans and the Ottoman Empire, while "Middle East" referred to the Caucasus, Persia, and Arabian lands,[20] and sometimes Afghanistan, India and others.[21] In contrast, "Far East" referred to the countries of East Asia (e.g. China, Japan, and Korea).[24][25]

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, "Near East" largely fell out of common use in English, while "Middle East" came to be applied to the emerging independent countries of the Islamic world. However, the usage "Near East" was retained by a variety of academic disciplines, including archaeology and ancient history. In their usage, the term describes an area identical to the term Middle East, which is not used by these disciplines (see ancient Near East).[citation needed]

The first official use of the term "Middle East" by the United States government was in the 1957 Eisenhower Doctrine, which pertained to the Suez Crisis. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles defined the Middle East as "the area lying between and including Libya on the west and Pakistan on the east, Syria and Iraq on the North and the Arabian peninsula to the south, plus the Sudan and Ethiopia."[19] In 1958, the State Department explained that the terms "Near East" and "Middle East" were interchangeable, and defined the region as including only Egypt, Syria, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar.[26]

Since the late 20th century, scholars and journalists from the region, such as journalist Louay Khraish and historian Hassan Hanafi have criticized the use of "Middle East" as a Eurocentric and colonialist term.[2][3][27]

The Associated Press Stylebook of 2004 says that Near East formerly referred to the farther west countries while Middle East referred to the eastern ones, but that now they are synonymous. It instructs:

Use Middle East unless Near East is used by a source in a story. Mideast is also acceptable, but Middle East is preferred.[28]

Translations

European languages have adopted terms similar to Near East and Middle East. Since these are based on a relative description, the meanings depend on the country and are generally different from the English terms. In German the term Naher Osten (Near East) is still in common use (nowadays the term Mittlerer Osten is more and more common in press texts translated from English sources, albeit having a distinct meaning).

In the four Slavic languages, Russian Ближний Восток or Blizhniy Vostok, Bulgarian Близкия Изток, Polish Bliski Wschód or Croatian Bliski istok (terms meaning Near East are the only appropriate ones for the region.

However, some European languages do have "Middle East" equivalents, such as French Moyen-Orient, Swedish Mellanöstern, Spanish Oriente Medio or Medio Oriente, Greek is Μέση Ανατολή (Mesi Anatoli), and Italian Medio Oriente.[note 2]

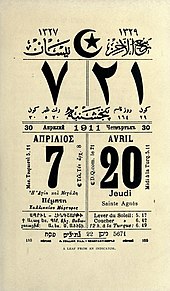

Perhaps because of the political influence of the United States and Europe, and the prominence of Western press, the Arabic equivalent of Middle East (Arabic: الشرق الأوسط ash-Sharq al-Awsaṭ) has become standard usage in the mainstream Arabic press. It comprises the same meaning as the term "Middle East" in North American and Western European usage. The designation, Mashriq, also from the Arabic root for East, also denotes a variously defined region around the Levant, the eastern part of the Arabic-speaking world (as opposed to the Maghreb, the western part).[29] Even though the term originated in the West, countries of the Middle East that use languages other than Arabic also use that term in translation. For instance, the Persian equivalent for Middle East is خاورمیانه (Khāvar-e miyāneh), the Hebrew is המזרח התיכון (hamizrach hatikhon), and the Turkish is Orta Doğu.

Countries and territory

Countries and territory usually considered within the Middle East

Traditionally included within the Middle East are Arabia, Asia Minor, East Thrace, Egypt, Iran, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and the Socotra Archipelago. The region includes 17 UN-recognized countries and one British Overseas Territory.

| Arms | Flag | Country | Area (km2) |

Population (2024)[30] |

Density (per km2) |

Capital | Nominal GDP, bn (2024)[30] |

GDP per capita (2024)[30] | Currency | Government | Official language(s) |

Predominant religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akrotiri and Dhekelia | 254 | 18,195 | 72 | Episkopi | N/A | N/A | Euro | De facto stratocratic dependency under a constitutional monarchy | English | Christianity | ||

| Bahrain | 780 | 1,617,000 | 2,073 | Manama | $47.812 | $29,573 | Bahraini dinar | Constitutional monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Cyprus | 9,250 | 921,000 | 100 | Nicosia | $34.790 | $37,767 | Euro | Presidential republic | Greek, Turkish |

Christianity | ||

| Egypt | 1,010,407 | 107,304,000 | 106 | Cairo | $380.044 | $3,542 | Egyptian pound | Semi-presidential republic | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Iran | 1,648,195 | 86,626,000 | 53 | Tehran | $434.243 | $5,013 | Iranian rial | Islamic republic | Persian | Islam (official) | ||

| Iraq | 438,317 | 44,415,000 | 101 | Baghdad | $264.149 | $5,947 | Iraqi dinar | Parliamentary republic | Arabic, Kurdish |

Islam (official, expect in autonomous Kurdistan Region) | ||

| Israel | 20,770 | 9,943,000 | 479 | Jerusalema | $528.067 | $53,111 | Israeli shekel | Parliamentary republic | Hebrew | Judaism | ||

| Jordan | 92,300 | 11,385,000 | 123 | Amman | $53.305 | $4,682 | Jordanian dinar | Constitutional monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Kuwait | 17,820 | 5,012,000 | 282 | Kuwait City | $161.822 | $32,290 | Kuwaiti dinar | Constitutional monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Lebanon | 10,452 | 5,354,000 (2023) | 512 | Beirut | $24.023 (2023) | $4,487 (2023) | Lebanese pound | Parliamentary republic | Arabic | Islam, large minority for Christianity | ||

| Oman | 309,500 | 5,331,000 | 17 | Muscat | $109.993 | $20,631 | Omani rial | Absolute monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Palestine | 6,220 | 5,477,000 (2023) | 881 | Jerusalem Ramallaha |

$17.421 (2023) | $3,181 (2023) | Israeli shekel, Jordanian dinar |

Semi-presidential republic | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Qatar | 11,437 | 3,094,000 | 271 | Doha | $221.406 | $71,568 | Qatari riyal | Constitutional monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 2,149,690 | 33,475,000 | 16 | Riyadh | $1,100.706 | $32,881 | Saudi riyal | Absolute monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Syria | 185,180 | 21,393,000 (2010) | 116 | Damascus | $60.043 (2010) | $2,807 (2010) | Syrian pound | Presidential republic | Arabic | Islam | ||

| Turkey | 783,562 | 85,811,000 | 110 | Ankara | $1,344.318 | $15,666 | Turkish lira | Presidential republic | Turkish | Islam | ||

| United Arab Emirates | 82,880 | 11,000,000 | 133 | Abu Dhabi | $545.053 | $49,550 | Emirati dirham | Federal constitutional monarchy | Arabic | Islam (official) | ||

| Yemen | 527,970 | 34,829,000 | 66 | Sanaab Aden (provisional) |

$16.192 | $465 | Yemeni rial | Provisional presidential republic | Arabic | Islam (official) |

- a. ^ ^ Jerusalem is the proclaimed capital of Israel, which is disputed, and the actual location of the Knesset, Israeli Supreme Court, and other governmental institutions of Israel. Ramallah is the actual location of the government of Palestine, whereas the proclaimed capital of Palestine is East Jerusalem, which is disputed.

- b. ^ Controlled by the Houthis due to the ongoing civil war. Seat of government moved to Aden.

Other definitions of the Middle East

Various concepts are often paralleled to the Middle East, most notably the Near East, Fertile Crescent, and Levant. These are geographical concepts, which refer to large sections of the modern-day Middle East, with the Near East being the closest to the Middle East in its geographical meaning. Due to it primarily being Arabic speaking, the Maghreb region of North Africa is sometimes included.

The countries of the South Caucasus – Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia – are occasionally included in definitions of the Middle East.[31]

"Greater Middle East" is a political term coined by the second Bush administration in the first decade of the 21st century[32] to denote various countries, pertaining to the Muslim world, specifically Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey.[33] Various Central Asian countries are sometimes also included.[34]

History

The Middle East lies at the juncture of Africa and Eurasia and of the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (see also: Indo-Mediterranean). It is the birthplace and spiritual center of religions such as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Manichaeism, Yezidi, Druze, Yarsan, and Mandeanism, and in Iran, Mithraism, Zoroastrianism, Manicheanism, and the Baháʼí Faith. Throughout its history the Middle East has been a major center of world affairs; a strategically, economically, politically, culturally, and religiously sensitive area. The region is one of the regions where agriculture was independently discovered, and from the Middle East it was spread, during the Neolithic, to different regions of the world such as Europe, the Indus Valley and Eastern Africa.

Prior to the formation of civilizations, advanced cultures formed all over the Middle East during the Stone Age. The search for agricultural lands by agriculturalists, and pastoral lands by herdsmen meant different migrations took place within the region and shaped its ethnic and demographic makeup.

The Middle East is widely and most famously known as the cradle of civilization. The world's earliest civilizations, Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia), ancient Egypt and Kish in the Levant, all originated in the Fertile Crescent and Nile Valley regions of the ancient Near East. These were followed by the Hittite, Greek, Hurrian and Urartian civilisations of Asia Minor; Elam, Persia and Median civilizations in Iran, as well as the civilizations of the Levant (such as Ebla, Mari, Nagar, Ugarit, Canaan, Aramea, Mitanni, Phoenicia and Israel) and the Arabian Peninsula (Magan, Sheba, Ubar). The Near East was first largely unified under the Neo Assyrian Empire, then the Achaemenid Empire followed later by the Macedonian Empire and after this to some degree by the Iranian empires (namely the Parthian and Sassanid Empires), the Roman Empire and Byzantine Empire. The region served as the intellectual and economic center of the Roman Empire and played an exceptionally important role due to its periphery on the Sassanid Empire. Thus, the Romans stationed up to five or six of their legions in the region for the sole purpose of defending it from Sassanid and Bedouin raids and invasions.

From the 4th century CE onwards, the Middle East became the center of the two main powers at the time, the Byzantine Empire and the Sassanid Empire. However, it would be the later Islamic Caliphates of the Middle Ages, or Islamic Golden Age which began with the Islamic conquest of the region in the 7th century AD, that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant Islamic Arab ethnic identity that largely (but not exclusively) persists today. The 4 caliphates that dominated the Middle East for more than 600 years were the Rashidun Caliphate, the Umayyad caliphate, the Abbasid caliphate and the Fatimid caliphate. Additionally, the Mongols would come to dominate the region, the Kingdom of Armenia would incorporate parts of the region to their domain, the Seljuks would rule the region and spread Turko-Persian culture, and the Franks would found the Crusader states that would stand for roughly two centuries. Josiah Russell estimates the population of what he calls "Islamic territory" as roughly 12.5 million in 1000 – Anatolia 8 million, Syria 2 million, and Egypt 1.5 million.[36] From the 16th century onward, the Middle East came to be dominated, once again, by two main powers: the Ottoman Empire and the Safavid dynasty.

The modern Middle East began after World War I, when the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with the Central Powers, was defeated by the British Empire and their allies and partitioned into a number of separate nations, initially under British and French Mandates. Other defining events in this transformation included the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the eventual departure of European powers, notably Britain and France by the end of the 1960s. They were supplanted in some part by the rising influence of the United States from the 1970s onwards.

In the 20th century, the region's significant stocks of crude oil gave it new strategic and economic importance. Mass production of oil began around 1945, with Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kuwait, Iraq, and the United Arab Emirates having large quantities of oil.[37] Estimated oil reserves, especially in Saudi Arabia and Iran, are some of the highest in the world, and the international oil cartel OPEC is dominated by Middle Eastern countries.

During the Cold War, the Middle East was a theater of ideological struggle between the two superpowers and their allies: NATO and the United States on one side, and the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact on the other, as they competed to influence regional allies. Besides the political reasons there was also the "ideological conflict" between the two systems. Moreover, as Louise Fawcett argues, among many important areas of contention, or perhaps more accurately of anxiety, were, first, the desires of the superpowers to gain strategic advantage in the region, second, the fact that the region contained some two-thirds of the world's oil reserves in a context where oil was becoming increasingly vital to the economy of the Western world [...][38] Within this contextual framework, the United States sought to divert the Arab world from Soviet influence. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the region has experienced both periods of relative peace and tolerance and periods of conflict particularly between Sunnis and Shiites.

Demographics

Ethnic groups

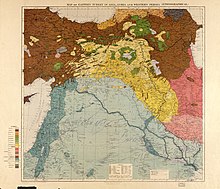

Arabs constitute the largest ethnic group in the Middle East, followed by various Iranian peoples and then by Turkic peoples (Turkish, Azeris, Syrian Turkmen, and Iraqi Turkmen). Native ethnic groups of the region include, in addition to Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Baloch, Berbers, Copts, Druze, Greek Cypriots, Jews, Kurds, Lurs, Mandaeans, Persians, Samaritans, Shabaks, Tats, and Zazas. European ethnic groups that form a diaspora in the region include Albanians, Bosniaks, Circassians (including Kabardians), Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Franco-Levantines, Italo-Levantines, and Iraqi Turkmens. Among other migrant populations are Chinese, Filipinos, Indians, Indonesians, Pakistanis, Pashtuns, Romani, and Afro-Arabs.

Migration

"Migration has always provided an important vent for labor market pressures in the Middle East. For the period between the 1970s and 1990s, the Arab states of the Persian Gulf in particular provided a rich source of employment for workers from Egypt, Yemen and the countries of the Levant, while Europe had attracted young workers from North African countries due both to proximity and the legacy of colonial ties between France and the majority of North African states."[39]

According to the International Organization for Migration, there are 13 million first-generation migrants from Arab nations in the world, of which 5.8 reside in other Arab countries. Expatriates from Arab countries contribute to the circulation of financial and human capital in the region and thus significantly promote regional development. In 2009 Arab countries received a total of US$35.1 billion in remittance in-flows and remittances sent to Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon from other Arab countries are 40 to 190 per cent higher than trade revenues between these and other Arab countries.[40] In Somalia, the Somali Civil War has greatly increased the size of the Somali diaspora, as many of the best educated Somalis left for Middle Eastern countries as well as Europe and North America.

Non-Arab Middle Eastern countries such as Turkey, Israel and Iran are also subject to important migration dynamics.

A fair proportion of those migrating from Arab nations are from ethnic and religious minorities facing persecution and are not necessarily ethnic Arabs, Iranians or Turks.[citation needed] Large numbers of Kurds, Jews, Assyrians, Greeks and Armenians as well as many Mandeans have left nations such as Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey for these reasons during the last century. In Iran, many religious minorities such as Christians, Baháʼís, Jews and Zoroastrians have left since the Islamic Revolution of 1979.[41][42]

Religions

The Middle East is very diverse when it comes to religions, many of which originated there. Islam is the largest religion in the Middle East, but other faiths that originated there, such as Judaism and Christianity,[43] are also well represented. Christian communities have played a vital role in the Middle East,[44] and they represent 40.5% of Lebanon, where the Lebanese president, half of the cabinet, and half of the parliament follow one of the various Lebanese Christian rites. There are also important minority religions like the Baháʼí Faith, Yarsanism, Yazidism,[45] Zoroastrianism, Mandaeism, Druze,[46] and Shabakism, and in ancient times the region was home to Mesopotamian religions, Canaanite religions, Manichaeism, Mithraism and various monotheist gnostic sects.

Languages

The six top languages, in terms of numbers of speakers, are Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Kurdish, Modern Hebrew and Greek. About 20 minority languages are also spoken in the Middle East.

Arabic, with all its dialects, is the most widely spoken language in the Middle East, with Literary Arabic being official in all North African and in most West Asian countries. Arabic dialects are also spoken in some adjacent areas in neighbouring Middle Eastern non-Arab countries. It is a member of the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages. Several Modern South Arabian languages such as Mehri and Soqotri are also spoken in Yemen and Oman. Another Semitic language is Aramaic and its dialects are spoken mainly by Assyrians and Mandaeans, with Western Aramaic still spoken in two villages near Damascus, Syria. There is also an Oasis Berber-speaking community in Egypt where the language is also known as Siwa. It is a non-Semitic Afro-Asiatic sister language.

Persian is the second most spoken language. While it is primarily spoken in Iran and some border areas in neighbouring countries, the country is one of the region's largest and most populous. It belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the family of Indo-European languages. Other Western Iranic languages spoken in the region include Achomi, Daylami, Kurdish dialects, Semmani, Lurish, amongst many others.

The close third-most widely spoken language, Turkish, is largely confined to Turkey, which is also one of the region's largest and most populous countries, but it is present in areas in neighboring countries. It is a member of the Turkic languages, which have their origins in East Asia. Another Turkic language, Azerbaijani, is spoken by Azerbaijanis in Iran.

The fourth-most widely spoken language, Kurdish, is spoken in the countries of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, Sorani Kurdish is the second official language in Iraq (instated after the 2005 constitution) after Arabic.

Hebrew is the official language of Israel, with Arabic given a special status after the 2018 Basic law lowered its status from an official language prior to 2018. Hebrew is spoken and used by over 80% of Israel's population, the other 20% using Arabic. Modern Hebrew only began being spoken in the 20th century after being revived in the late 19th century by Elizer Ben-Yehuda (Elizer Perlman) and European Jewish settlers, with the first native Hebrew speaker being born in 1882.

Greek is one of the two official languages of Cyprus, and the country's main language. Small communities of Greek speakers exist all around the Middle East; until the 20th century it was also widely spoken in Asia Minor (being the second most spoken language there, after Turkish) and Egypt. During the antiquity, Ancient Greek was the lingua franca for many areas of the western Middle East and until the Muslim expansion it was widely spoken there as well. Until the late 11th century, it was also the main spoken language in Asia Minor; after that it was gradually replaced by the Turkish language as the Anatolian Turks expanded and the local Greeks were assimilated, especially in the interior.

English is one of the official languages of Akrotiri and Dhekelia.[47][48] It is also commonly taught and used as a foreign second language, in countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.[49][50] It is also a main language in some Emirates of the United Arab Emirates. It is also spoken as native language by Jewish immigrants from Anglophone countries (UK, US, Australia) in Israel and understood widely as second language there.

French is taught and used in many government facilities and media in Lebanon, and is taught in some primary and secondary schools of Egypt and Syria. Maltese, a Semitic language mainly spoken in Europe, is used by the Franco-Maltese diaspora in Egypt. Due to widespread immigration of French Jews to Israel, it is the native language of approximately 200,000 Jews in Israel.

Armenian speakers are to be found in the region. Georgian is spoken by the Georgian diaspora.

Russian is spoken by a large portion of the Israeli population, because of emigration in the late 1990s.[51] Russian today is a popular unofficial language in use in Israel; news, radio and sign boards can be found in Russian around the country after Hebrew and Arabic. Circassian is also spoken by the diaspora in the region and by almost all Circassians in Israel who speak Hebrew and English as well.

The largest Romanian-speaking community in the Middle East is found in Israel, where as of 1995[update] Romanian is spoken by 5% of the population.[note 3][52][53]

Bengali, Hindi and Urdu are widely spoken by migrant communities in many Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia (where 20–25% of the population is South Asian), the United Arab Emirates (where 50–55% of the population is South Asian), and Qatar, which have large numbers of Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian immigrants.

Culture

Sport

The Middle East has recently become more prominent in hosting global sport events due to its wealth and desire to diversify its economy.[54]

The South Asian diaspora is a major backer of cricket in the region.[55]

Economy

This section needs to be updated. (December 2016) |

Middle Eastern economies range from being very poor (such as Gaza and Yemen) to extremely wealthy nations (such as Qatar and UAE). Overall, as of 2007[update], according to the CIA World Factbook, all nations in the Middle East are maintaining a positive rate of growth.

According to the International Monetary Fund,[56] the three largest Middle Eastern economies in nominal GDP in 2023 were Saudi Arabia ($1.062 trillion), Turkey ($1.029 trillion), and Israel ($539 billion). Regarding nominal GDP per capita, the highest ranking countries are Qatar ($83,891), Israel ($55,535), the United Arab Emirates ($49,451) and Cyprus ($33,807).[56] Turkey ($3.573 trillion), Saudi Arabia ($2.301 trillion), and Iran ($1.692 trillion) had the largest economies in terms of GDP PPP.[56] When it comes to GDP PPP per capita, the highest-ranking countries are Qatar ($124,834), the United Arab Emirates ($88,221), Saudi Arabia ($64,836), Bahrain ($60,596) and Israel ($54,997). The lowest-ranking country in the Middle East, in terms of GDP nominal per capita, is Yemen ($573).[56]

The economic structure of Middle Eastern nations are different in the sense that while some nations are heavily dependent on export of only oil and oil-related products (such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait), others have a highly diverse economic base (such as Cyprus, Israel, Turkey and Egypt). Industries of the Middle Eastern region include oil and oil-related products, agriculture, cotton, cattle, dairy, textiles, leather products, surgical instruments, defence equipment (guns, ammunition, tanks, submarines, fighter jets, UAVs, and missiles). Banking is also an important sector of the economies, especially in the case of UAE and Bahrain.

With the exception of Cyprus, Turkey, Egypt, Lebanon and Israel, tourism has been a relatively undeveloped area of the economy, in part because of the socially conservative nature of the region as well as political turmoil in certain regions of the Middle East. In recent years,[when?] however, countries such as the UAE, Bahrain, and Jordan have begun attracting greater numbers of tourists because of improving tourist facilities and the relaxing of tourism-related restrictive policies.[citation needed]

Unemployment is notably high in the Middle East and North Africa region, particularly among young people aged 15–29, a demographic representing 30% of the region's total population. The total regional unemployment rate in 2005, according to the International Labour Organization, was 13.2%,[57] and among youth is as high as 25%,[58] up to 37% in Morocco and 73% in Syria.[59]

Climate change

Climate change in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) refers to changes in the climate of the MENA region and the subsequent response, adaption and mitigation strategies of countries in the region. In 2018, the MENA region emitted 3.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide and produced 8.7% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)[63] despite making up only 6% of the global population.[64] These emissions are mostly from the energy sector,[65] an integral component of many Middle Eastern and North African economies due to the extensive oil and natural gas reserves that are found within the region.[66][67] The region of Middle East is one of the most vulnerable to climate change. The impacts include increase in drought conditions, aridity, heatwaves and sea level rise.

Sharp global temperature and sea level changes, shifting precipitation patterns and increased frequency of extreme weather events are some of the main impacts of climate change as identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[68] The MENA region is especially vulnerable to such impacts due to its arid and semi-arid environment, facing climatic challenges such as low rainfall, high temperatures and dry soil.[68][69] The climatic conditions that foster such challenges for MENA are projected by the IPCC to worsen throughout the 21st century.[68] If greenhouse gas emissions are not significantly reduced, part of the MENA region risks becoming uninhabitable before the year 2100.[70][71][72]

Climate change is expected to put significant strain on already scarce water and agricultural resources within the MENA region, threatening the national security and political stability of all included countries.[73] Over 60 percent of the region's population lives in high and very high water-stressed areas compared to the global average of 35 percent.[74] This has prompted some MENA countries to engage with the issue of climate change on an international level through environmental accords such as the Paris Agreement. Law and policy are also being established on a national level amongst MENA countries, with a focus on the development of renewable energies.[75]See also

- Arab World

- Cinema of the Middle East

- Etiquette in the Middle East

- MENA – Geographic region

- Mental health in the Middle East

- Middle East Studies Association of North America – Learned society

- Middle Eastern cuisine – Culinary tradition

- Middle Eastern music – Music of the Middle Eastern region

- Orientalism – Imitation or depiction of Eastern culture

- Russia and the Middle East – Relationships between

- State feminism § Middle East

- Timeline of Middle Eastern history

Notes

- ^ Translations of this term in some of the region's major languages include: Arabic: الشرق الأوسط, romanized: aš-Šarq al-ʾAwsaṭ; Assyrian Neo-Aramaic: ܡܕܢܚܐ ܡܨܥܝܬܐ, romanized: Madnḥā Miṣʿāyā; Hebrew: הַמִּזְרָח הַתִּיכוֹן, romanized: ham-Mizrāḥ hat-Tīḵōn; Kurdish: Rojhilata Navîn; Persian: خاورمیانه, romanized: Xâvar-e-Miyâne; South Azerbaijani: اوْرتاشرق; Turkish: Orta Doğu.

- ^ In Italian, the expression "Vicino Oriente" (Near East) was widely used to refer to Turkey, and Estremo Oriente (Far East or Extreme East) to refer to all of Asia east of Middle East

- ^ According to the 1993 Statistical Abstract of Israel there were 250,000 Romanian speakers in Israel, at a population of 5,548,523 (census 1995).

References

- ^ "The Middle East Population". 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ a b Khraish, Louay (16 July 2021). "Don't Call Me Middle Eastern". Raseef 22.

- ^ a b Hanafi, Hassan (1998). "The Middle East, in whose world? (Primary Reflections)". Oslo: Nordic Society for Middle Eastern Studies (The fourth Nordic conference on Middle Eastern Studies: The Middle East in globalizing world Oslo, 13–16 August 1998). Archived from the original on 8 October 2006.

- ^ Cairo, Michael F. The Gulf: The Bush Presidencies and the Middle East Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine University Press of Kentucky, 2012 ISBN 978-0-8131-3672-1 p. xi.

- ^ Government Printing Office. History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense: The formative years, 1947–1950 Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-16-087640-0 p. 177

- ^ Kahana, Ephraim. Suwaed, Muhammad. Historical Dictionary of Middle Eastern Intelligence Archived 23 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Scarecrow Press, 13 April 2009 ISBN 978-0-8108-6302-6 p. xxxi.

- ^ MacQueen, Benjamin (2013). An Introduction to Middle East Politics: Continuity, Change, Conflict and Co-operation. SAGE. p. 5. ISBN 978-1446289761.

The Middle East is the cradle of the three monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

- ^ Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Beaumont, Blake & Wagstaff 1988, p. 16.

- ^ Koppes, CR (1976). "Captain Mahan, General Gordon and the origin of the term "Middle East"". Middle East Studies. 12: 95–98. doi:10.1080/00263207608700307. ISSN 0026-3206.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1965). The Middle East and the West. p. 9.

- ^ Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to end all Peace. H. Holt. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-8050-0857-9.

- ^ Melman, Billie (November 2002), Companion to Travel Writing, Collections Online, vol. 6 The Middle East/Arabia, Cambridge, archived from the original on 25 July 2011, retrieved 8 January 2006.

- ^ Palmer, Michael A. Guardians of the Persian Gulf: A History of America's Expanding Role in the Persian Gulf, 1833–1992. New York: The Free Press, 1992. ISBN 0-02-923843-9 pp. 12–13.

- ^ Laciner, Sedat. "Is There a Place Called 'the Middle East'? Archived 2007-02-20 at the Wayback Machine", The Journal of Turkish Weekly, 2 June 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ Adelson 1995, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Adelson 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Adelson 1995, p. 26.

- ^ a b Davison, Roderic H. (1960). "Where is the Middle East?". Foreign Affairs. 38 (4): 665–675. doi:10.2307/20029452. JSTOR 20029452. S2CID 157454140.

- ^ a b "How the Middle East was invented". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Where Is the Middle East? | Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies".

- ^ Held, Colbert C. (2000). Middle East Patterns: Places, Peoples, and Politics. Westview Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8133-8221-0.

- ^ Culcasi, Karen (2010). "Constructing and naturalizing the Middle Easr". Geographical Review. 100 (4): 583–597. Bibcode:2010GeoRv.100..583C. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2010.00059.x. JSTOR 25741178. S2CID 154611116.

- ^ Clyde, Paul Hibbert, and Burton F. Beers. The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975 (1975). online

- ^ Norman, Henry. The Peoples and Politics of the Far East: Travels and studies in the British, French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies, Siberia, China, Japan, Korea, Siam and Malaya (1904) online

- ^ "'Near East' is Mideast, Washington Explains". The New York Times. 14 August 1958. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.(subscription required)

- ^ Shohat, Ella. "Redrawing American Cartographies of Asia". City University of New York. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- ^ Goldstein, Norm. The Associated Press Stylebook and Briefing on Media Law. New York: Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0-465-00488-1 p. 156

- ^ Anderson, Ewan W.; William Bayne Fisher (2000). The Middle East: Geography and Geopolitics. Routledge. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Novikova, Gayane (December 2000). "Armenia and the Middle East" (PDF). Middle East Review of International Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Haeri, Safa (3 March 2004). "Concocting a 'Greater Middle East' brew". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2004. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ Ottaway, Marina & Carothers, Thomas (29 March 2004), The Greater Middle East Initiative: Off to a False Start Archived 12 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Policy Brief, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 29, pp. 1–7

- ^ Middle East Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine What Is The Middle East And What Countries Are Part of It? worldatlas.com. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "The World's First Temple". Archaeology magazine. November–December 2008. p. 23.

- ^ Russell, Josiah C. (1985). "The Population of the Crusader States". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Zacour, Norman P.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume V: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 295–314. ISBN 0-299-09140-6.

- ^ Goldschmidt (1999), p. 8

- ^ Louise, Fawcett. International Relations of the Middle East. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2005)

- ^ Hassan, Islam; Dyer, Paul (2017). "The State of Middle Eastern Youth". The Muslim World. 107 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1111/muwo.12175. hdl:10822/1042998. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017.

- ^ "IOM Intra regional labour mobility in Arab region Facts and Figures (English)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 276. ISBN 978-1838609344.

Although the Christians of Iran, unlike their Iraqi brothers, were not called up for military service in the Iran–Iraq War ... was so radical that a genuine exodus took place – more than half the 250,000 Christians left Iran after 1979.

- ^ Cecolin, Alessandra (2015). Iranian Jews in Israel: Between Persian Cultural Identity and Israeli Nationalism. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 978-0857727886.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (2020). The Rowman & Littlefield Handbook of Christianity in the Middle East. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xlviii. ISBN 978-1538124185.

The Middle East still stands at the heart of the Christian world. After all, it is the birthplace, and the death place, of Christ, and the cradle of the Christian tradition.

- ^ Curtis, Michael (2017). Jews, Antisemitism, and the Middle East. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 978-1351510721.

Christian communities and individuals have played a vital role in the Middle East, the cradle of Christianity as of other religions.

- ^ Nelida Fuccaro (1999). The Other Kurds: Yazidis in Colonial Iraq. London & New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 9. ISBN 1860641709.

- ^ C. Held, Colbert (2008). Middle East Patterns: Places, People, and Politics. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-0429962004.

Worldwide, they number 1 million or so, with about 45 to 50 percent in Syria, 35 to 40 percent in Lebanon, and less than 10 percent in Israel. Recently there has been a growing Druze diaspora.

- ^ "Europe :: Akrotiri – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". CIA. 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Europe :: Dhekelia – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". CIA. 25 October 2021.

- ^ "World Factbook – Jordan". 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Kuwait". Central Intelligence Agency. 19 October 2021 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ Dowty, Alan (2004). Critical issues in Israeli society. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 95. ISBN 9780275973209.

- ^ "Reports of about 300,000 Jews that left the country after WW2". Eurojewcong.org. Archived from the original on 13 August 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Evenimentul Zilei". Evz.ro. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "How the Middle East became the sports industry's go-to destination". gis.sport. 2024-08-22. Retrieved 2024-10-23.

- ^ Kanchana, Radhika (2020-06-29). "Cricket, an oddity in the Arab-Gulf lands or a mirror of an enduring South Asian diaspora?". Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos (28): 121–135. doi:10.15366/reim2020.28.007. ISSN 1887-4460.

- ^ a b c d International Monetary Fund. "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "Unemployment Rates Are Highest in the Middle East". Progressive Policy Institute. 30 August 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Navtej Dhillon; Tarek Yousef (2007). "Inclusion: Meeting the 100 Million Youth Challenge". Shabab Inclusion. Archived from the original on 9 November 2008.

- ^ Hilary Silver (12 December 2007). "Social Exclusion: Comparative Analysis of Europe and Middle East Youth". Middle East Youth Initiative Working Paper. Shabab Inclusion. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ "CO2 Emissions". Global Carbon Atlas. Archived from the original on Oct 11, 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ^ "Population, total – Middle East & North Africa, World". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ Abbass, Rana Alaa; Kumar, Prashant; El-Gendy, Ahmed (February 2018). "An overview of monitoring and reduction strategies for health and climate change related emissions in the Middle East and North Africa region" (PDF). Atmospheric Environment. 175: 33–43. Bibcode:2018AtmEn.175...33A. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.11.061. ISSN 1352-2310. Archived (PDF) from the original on Jun 14, 2021 – via Surrey Research Insight Open Access.

- ^ Al-mulali, Usama (2011-10-01). "Oil consumption, CO2 emission and economic growth in MENA countries". Energy. 36 (10): 6165–6171. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2011.07.048. ISSN 0360-5442.

- ^ Tagliapietra, Simone (2019-11-01). "The impact of the global energy transition on MENA oil and gas producers". Energy Strategy Reviews. 26: 100397. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2019.100397. ISSN 2211-467X.

- ^ a b c IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

- ^ El-Fadel, M.; Bou-Zeid, E. (2003). "Climate change and water resources in the Middle East: vulnerability, socio-economic impacts and adaptation". Climate Change in the Mediterranean. doi:10.4337/9781781950258.00015. hdl:10535/6396. ISBN 9781781950258.

- ^ Broom, Douglas (5 April 2019). "How the Middle East is suffering on the front lines of climate change". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Gornall, Jonathan (24 April 2019). "With climate change, life in the Gulf could become impossible". Euroactive. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Pal, Jeremy S.; Eltahir, Elfatih A. B. (2015-10-26). "Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability". Nature Climate Change. 6 (2): 197–200. doi:10.1038/nclimate2833. ISSN 1758-678X.

- ^ Waha, Katharina; Krummenauer, Linda; Adams, Sophie; Aich, Valentin; Baarsch, Florent; Coumou, Dim; Fader, Marianela; Hoff, Holger; Jobbins, Guy; Marcus, Rachel; Mengel, Matthias (2017-04-12). "Climate change impacts in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region and their implications for vulnerable population groups" (PDF). Regional Environmental Change. 17 (6): 1623–1638. Bibcode:2017REnvC..17.1623W. doi:10.1007/s10113-017-1144-2. hdl:1871.1/15a62c49-fde8-4a54-95ea-dc32eb176cf4. ISSN 1436-3798. S2CID 134523218. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12.

- ^ Giovanis, Eleftherios; Ozdamar, Oznur (2022-06-13). "The impact of climate change on budget balances and debt in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region". Climatic Change. 172 (3): 34. Bibcode:2022ClCh..172...34G. doi:10.1007/s10584-022-03388-x. ISSN 1573-1480. PMC 9191535. PMID 35729894.

- ^ Brauch, Hans Günter (2012), "Policy Responses to Climate Change in the Mediterranean and MENA Region during the Anthropocene", Climate Change, Human Security and Violent Conflict, Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, vol. 8, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 719–794, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28626-1_37, ISBN 978-3-642-28625-4

Sources

- Adelson, Roger (1995). London and the Invention of the Middle East: Money, Power, and War, 1902–1922. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06094-2.

- Beaumont, Peter; Blake, Gerald H; Wagstaff, J. Malcolm (1988). The Middle East: A Geographical Study. David Fulton. ISBN 978-0-470-21040-6.

Further reading

- Anderson, R; Seibert, R; Wagner, J. (2006). Politics and Change in the Middle East (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Barzilai, Gad; Aharon, Klieman; Gil, Shidlo (1993). The Gulf Crisis and its Global Aftermath. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08002-6.

- Barzilai, Gad (1996). Wars, Internal Conflicts and Political Order. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2943-3.

- Bishku, Michael B. (2015). "Is the South Caucasus Region a Part of the Middle East?". Journal of Third World Studies. 32 (1): 83–102. JSTOR 45178576.

- Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. A History Of The Modern Middle East (6th ed. 2018 4th ed. online

- Cressey, George B. (1960). Crossroads: Land and Life in Southwest Asia. Chicago, IL: J.B. Lippincott Co. xiv, 593 pp. ill. with maps and b&w photos.

- Fischbach, ed. Michael R. Biographical encyclopedia of the modern Middle East and North Africa (Gale Group, 2008).

- Freedman, Robert O. (1991). The Middle East from the Iran-Contra Affair to the Intifada, in series, Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. 1st ed. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. x, 441 pp. ISBN 0-8156-2502-2 pbk.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur Jr (1999). A Concise History of the Middle East. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0471-7.

- Halpern, Manfred. Politics of Social Change: In the Middle East and North Africa (Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Ismael, Jacqueline S., Tareq Y. Ismael, and Glenn Perry. Government and politics of the contemporary Middle East: Continuity and change (Routledge, 2015).

- Lynch, Marc, ed. The Arab Uprisings Explained: New Contentious Politics in the Middle East (Columbia University Press, 2014). p. 352.

- Palmer, Michael A. (1992). Guardians of the Persian Gulf: A History of America's Expanding Role in the Persian Gulf, 1833–1992. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-923843-1.

- Reich, Bernard. Political leaders of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa: a biographical dictionary (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1990).

- Vasiliev, Alexey. Russia's Middle East Policy: From Lenin to Putin (Routledge, 2018).

External links

- "Middle East – Articles by Region" Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Council on Foreign Relations: "A Resource for Nonpartisan Research and Analysis"

- "Middle East – Interactive Crisis Guide" Archived 30 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Council on Foreign Relations: "A Resource for Nonpartisan Research and Analysis"

- Middle East Department University of Chicago Library

- Middle East Business Intelligence since 1957: "The leading information source on business in the Middle East" – meed.com

- Carboun – advocacy for sustainability and environmental conservation in the Middle East

- Middle East News from Yahoo! News

- Middle East Business, Financial & Industry News – ArabianBusiness.com