Royal Ontario Museum

| |

| |

| Established | 16 April 1912 |

|---|---|

| Location | 100 Queen's Park Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6 |

| Coordinates | 43°40′04″N 79°23′41″W / 43.667679°N 79.394809°W |

| Collection size | 18,000,000+ |

| Visitors | 1,440,000[1] |

| Director | Josh Basseches |

| Owner | Government of Ontario |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

| Built | 1910–1914, addition: 1931–32 |

| Architect | Darling & Pearson, addition: Chapman & Oxley |

| Sculptor | Wm. Oosterhoff |

| Designated | 2003 |

| Reference no. | Heritage Easement Agreement AT347470 |

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) is a museum of art, world culture and natural history in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is one of the largest museums in North America and the largest in Canada. It attracts more than one million visitors every year, making it the most-visited museum in Canada.[2] It is north of Queen's Park, in the University of Toronto district, with its main entrance on Bloor Street West. Museum subway station is named after it and, since a 2008 renovation, is decorated to resemble the ROM's collection at the platform level; Museum station's northwestern entrance directly serves the museum.

Established on April 16, 1912, and opened on March 19, 1914, the ROM has maintained close relations with the University of Toronto throughout its history, often sharing expertise and resources.[3] It was under direct control and management of the University of Toronto until 1968, when it became an independent Crown agency of the Government of Ontario.[4][5] It is Canada's largest field-research institution, with research and conservation activities worldwide.[6]

With more than 18 million items and 40 galleries, the museum's diverse collections of world culture and natural history contribute to its international reputation.[6] It contains a collection of dinosaurs, minerals and meteorites; Canadian and European historical artifacts; as well as African, Near Eastern, and East Asian art. It houses the world's largest collection of fossils from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia with more than 150,000 specimens.[7] The museum also contains an extensive collection of design and fine art, including clothing, interior, and product design, especially Art Deco.

History

[edit]

The Royal Ontario Museum was formally established on April 16, 1912,[8][9] and was jointly governed by the Government of Ontario and the University of Toronto.[10] Its first assets were transferred from the university and the Ontario Department of Education,[8] coming from its predecessor, the Museum of Natural History and Fine Arts at the Toronto Normal School.[11] On 19 March 1914, the Duke of Connaught, also the governor general of Canada, officially opened the Royal Ontario Museum to the public.[9] The museum's location at the edge of Toronto's built-up area, far from the city's central business district, was selected mainly for its proximity to the University of Toronto. The original building was constructed on the western edge of the property along the university's Philosopher's Walk, with its main entrance facing out onto Bloor Street housing five separate museums of the following fields: Archaeology, Palaeontology, Mineralogy, Zoology, and Geology.[9] It cost CA$400,000 to construct.[12] This was the first phase of a two-part construction plan intended to expand toward Queen's Park Crescent, ultimately creating an H-shaped structure.

The first expansion to the Royal Ontario Museum publicly opened on October 12, 1933.[13] The CA$1.8-million[12] renovation saw the construction of the east wing fronting onto Queen's Park and required the demolition of Argyle House, a Victorian mansion at 100 Queen's Park. As this occurred during the Great Depression, an effort was made to use primarily local building materials and to make use of workers capable of manually excavating the building's foundations.[13] Teams of workers alternated weeks of service due to the physically draining nature of the job.

In 1947, the ROM was dissolved as a body corporate, with all assets transferred to the University of Toronto.[14] The museum remained a part of the university until 1968, when the museum and the McLaughlin Planetarium were separated from the university to form a new corporation.[15]

On 26 October 1968, the ROM opened the McLaughlin Planetarium on the south end of the property after receiving a CA$2 million donation from Colonel Samuel McLaughlin.[16] In December 1995, the ROM closed the McLaughlin Planetarium as a result of budgetary cutbacks imposed by the Government of Ontario.[17] The space temporarily reopened from 1998 to 2002, after being leased to Children's Own Museum. In 2009, the ROM sold the building to the University of Toronto for CA$22 million and ensured that it would continue to be used for institutional and academic purposes.[18][19]

The second major addition to the museum was the Queen Elizabeth II Terrace Galleries on the north side of the building and a curatorial centre built on the south, which started in 1978 and was completed in 1984. The new construction meant that a former outdoor "Chinese Garden" to the north of the building facing Bloor, along with an adjoining indoor restaurant, had to be dismantled. Opened in 1984 by Queen Elizabeth II, the CA$55 million expansion took the form of layered terraces, each rising layer stepping back from Bloor Street. The design of this expansion won a Governor-General's Award in Architecture.[20]

In 1989, activists complained about its Into the Heart of Africa exhibit, which featured stereotypes of Africans, forcing curator Jeanne Cannizzo to resign.[21]

Beginning in 2002, the museum underwent a major renovation and expansion project dubbed as Renaissance ROM.[22] The Ontario and Canadian governments, both supporters of this venture, contributed $60 million toward the project,[22][23] and Michael Lee-Chin donated $30 million.[22] The campaign aimed not only to raise annual visitor attendance from 750,000 to between 1.4 and 1.6 million,[24] but also to generate additional funding opportunities to support the museum's research, conservation, galleries and educational public programs.[25] The centrepiece of the project was a deconstructivist crystalline-form structure called the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal. The structure was created by architect Daniel Libeskind,[22] whose design was selected from among 50 finalists in an international competition.[26] The design of the Crystal required the Terrace Galleries to be torn down (the curatorial centre to the south remains). Existing galleries and buildings were also upgraded, along with the installation of multiple new exhibits over a period of months. The first phase of the Renaissance ROM project, the "Ten Renovated Galleries in the Historic Buildings", opened to the public on 26 December 2005.[27] The architectural opening of the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal took place less than 18 months later, on 2 June 2007.[27] The final cost of the project was about CA$270 million.[28]

The original building was listed by the City of Toronto on the Municipal Heritage Register on 20 June 1973, designated under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act in 2003, with a Heritage Easement on the buildings.[29]

OpenROM renovation

[edit]Much of the museum's Bloor Street–facing side is being renovated since February 2024, as well as correcting architectural deficiencies to the Crystal while respecting Libeskind's original architectural design. Renovations include an expanded skylight to provide more natural lighting to its atrium, as well as an additional staircase within the atrium, as well as the reconstruction of the entrance plaza.[30][31]

Buildings and architecture

[edit]Original building and eastern wing

[edit]

Designed by Toronto architects Frank Darling and John A. Pearson,[32] the architectural style of the original building (now the western wing) is a synthesis of Italianate and Neo-Romanesque.[33] The structure is heavily massed and punctuated by rounded and segmented arched windows with heavy surrounds and hood mouldings. Other features include applied decorative eave brackets, quoins and cornices.

The eastern wing facing Queen's Park was designed by Alfred H. Chapman and James Oxley. Opened in 1933, it included the museum's elaborate art deco, Byzantine-inspired rotunda and a new main entrance. The linking wing and rear (west) façade of the Queen's Park wing were originally done in the same yellow brick as the 1914 building, with minor Italianate detailing. This façade broke away from the heavy Italianate style of the original structure. It was built in a neo-Byzantine style with rusticated stone, triple windows contained within recessed arches and different-coloured stones arranged in a variety of patterns.[33] This development from the Roman-inspired Italianate to a Byzantine-influenced style reflected the historical development of Byzantine architecture from Roman architecture. Common among neo-Byzantine buildings in North America, the façade also contains elements of Gothic Revival in its relief carvings, gargoyles and statues. The ornate ceiling of the rotunda is covered predominantly in gold back painted glass mosaic tiles, with coloured mosaic geometric patterns and images of real and mythical animals.

Writing in the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada in 1933, A. S. Mathers said of the expansion:[34]

The interior of the building is a surprise and a pleasant one; the somewhat complicated ornament of the façade is forgotten and a plan on the grand manner unfolds itself. It is simple, direct and big in scale. One is convinced that the early Beaux-Arts training of the designer has not been in vain. The outstanding feature of the interior is the glass mosaic ceiling of the entrance rotunda. It is executed in colours and gold and strikes a fine note in the one part of the building which the architect could decorate without conflicting with the exhibits.

The original building and the 1933 expansion have been listed since 1973 as heritage buildings of Toronto.[35] In 2005, a major renovation of the heritage wings saw the galleries made larger, windows uncovered, and the original early 20th-century architecture made more prominent. The exteriors of the heritage buildings were cleaned and restored. The restoration of the 1914 and 1933 buildings was the largest heritage project undertaken in Canada.[36] The renovation also included the newly restored Rotunda with reproductions of the original oak doors, a restored axial view from the Rotunda west through to windows onto Philosophers' Walk and ten renovated galleries comprising a total of 8,000 square metres (90,000 sq ft).[37]

In the master plan designed by Darling and Pearson in 1909, the ROM took a form similar to that of J. N. L. Durand's ideal model of the museum.[38] It was envisioned as a square plan with corridors running through the centre of the composition, converging in the middle with a domed rotunda. Overall, it referenced the upper-class palaces of the 17th and 18th centuries and aimed at having a strong sense of monumentality. All the architectural elements—the deep cornice, decorative top, eave brackets—add to this strength that the ROM possessed, as it was purely a structure with the function of collecting, but not of exhibiting.[39]

During the mid-2010s, the eastern entrance was used as a café. Since late 2017, the eastern entrance is undergoing renovation to become an alternate entrance, complete with the addition of ramps to the eastern entrance. The eastern entrance is a few steps from the main entrance to Museum station.

Curatorial centre

[edit]

Designed by Toronto architect Gene Kinoshita, with Mathers & Haldenby, the curatorial centre forms the southern section of the museum. Completed in 1984, it was built during the same expansion as the former Queen Elizabeth II Terrace Galleries, which stood on the north side of the museum before the terrace galleries were replaced with the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal. The architecture is a simple modernist style of poured concrete, glass, and pre-cast concrete and aggregate panels. The curatorial centre houses the museum's administrative and curatorial services and provides storage for artifacts that are not on exhibit. In 2006, the curatorial centre was renamed to Louise Hawley Stone Curatorial Centre in honour of the late Louise Hawley Stone, who donated a number of artifacts and various collections to the museum. In her will, she transferred C$49.7 million to the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust, created to help with the upkeep of the building and to the acquisition of new artifacts.[40]

Michael Lee-Chin Crystal

[edit]Replacing the Queen Elizabeth II Terrace Galleries was the controversial "Michael Lee-Chin Crystal", a multimillion-dollar expansion to the museum designed by Daniel Libeskind, including a new sliding door entrance on Bloor Street, first opened in 2007.[41][42] The Deconstructivist crystalline form is clad in 25 percent glass and 75 percent aluminum, sitting on top of a steel frame. The Crystal's canted walls do not touch the sides of the existing heritage buildings but are used to close the envelope between the new form and existing walls. These walls act as a pathway for pedestrians to travel safely across the Crystal.

The building's design is similar to some of Libeskind's other works, notably the Jewish Museum in Berlin, the London Metropolitan University Graduate Centre and the Fredric C. Hamilton Building at the Denver Art Museum.[43] The steel framework was manufactured and assembled by Walters Inc. of Hamilton, Ontario. The extruded anodized aluminum cladding was fabricated by Josef Gartner in Germany, the only company in the world that can produce the material.[36] The company also provided the titanium cladding for Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.[36]

On 1 June 2007, the governor-general of Canada, Michaëlle Jean, attended the Crystal's architectural opening.[44] This caused controversy because public opinion had been divided concerning the merits of its angular design. On its opening, Globe and Mail architecture critic Lisa Rochon complained that "the new ROM rages at the world", was oppressive, angsty and hellish,[45] while others—perhaps championed by her Toronto Star counterpart, Christopher Hume—hailed it as a monument.[46] Some critics have ranked it as one of the ten ugliest buildings in the world.[47] The project also experienced budget and construction time over-runs,[48] and drew comparisons to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao for using so-called "starchitecture" to attract tourism.[49]

The main lobby is a three-storey high atrium, named the Hyacinth Gloria Chen Crystal Court.[50] The lobby is overlooked by balconies and flanked by the J. P. Driscoll Family Stair of Wonders and the Spirit House, an interstitial space formed by the intersection of the east and west crystals.[51]

Installation of the permanent galleries of the Lee-Chin Crystal began mid-June 2007, after a ten-day period when all the empty gallery spaces were open to the public.[52] Within the Crystal there is a gift shop, C5 restaurant lounge (closed until further notice), a cafeteria, seven additional galleries and Canada's largest temporary exhibition hall in a museum. The galleries added to the Crystal gave different aspects to the ROM: fascinating visuals, architectural artifacts and environment, art, correspondence between object and space and stories within the visuals.[53] The C5 restaurant Lounge is designed by IV Design Associated Inc.[54]

In October 2007, the Lee-Chin Crystal was reported to have suffered from significant water leakage, causing concerns for the building's resilience to weather, especially in the face of the new structure's proximate first winter.[55] Although a two-layer cladding system was incorporated into the design of the Crystal to prevent the formation of dangerous snow loads on the structure, past architectural creations of Daniel Libeskind (including the Denver Art Museum) have also suffered from weather-related complications.[56][57]

Offsite storage

[edit]Collections at the ROM not displayed at the ROM itself or in other museums are stored in various unclassified and offsite locations around the Greater Toronto Area.

Galleries

[edit]Originally, there were five major galleries at the ROM, one each for the fields of archaeology, geology, mineralogy, paleontology and zoology.[9][58] In general, the museum pieces were labelled and arranged in a static fashion that had changed little since Edwardian times. For example, the insects' exhibit that lasted up until the 1970s housed a variety of specimens from different parts of the world in long rows of glass cases. Insects of the same genus were pinned to the inside of the cabinet, with only the species name and location found as a description.

By the 1960s, more interpretive displays were ushered in, among the first being the original dinosaur gallery, established in the mid-1960s. Dinosaur fossils were now staged in dynamic poses against backdrop paintings and models of contemporaneous landscapes and vegetation. The displays became more descriptive and interpretive sometimes, as with the extinction of the woolly mammoth, offering several different leading theories on the issue for the visitor to ponder. This trend continued and up until the present day, the galleries became less staid and more dynamic or descriptive and interpretive. This trend arguably came to a culmination in the 1980s with the opening of The Bat Cave, where a sound system, strobe lights and gentle puffs of air attempts to recreate the experience of walking through a cave as a colony of bats fly out.

The original galleries were simply named after their subject material, but in more recent years, individual galleries have been named in honour of sponsors who have donated significant funds or collections to the institution. There are now two main categories of galleries present in the ROM: the Natural History Galleries and the World Culture Galleries.

The Samuel Hall Currelly Gallery is an exhibition space on Level 1, connecting the east wing of the museum with its western half. The gallery serves as the building's main lobby past the museum's admission area. As opposed to most galleries at the Royal Ontario Museum, the Samuel Hall Currelly Gallery is not dedicated to a single subject. Instead, the gallery exhibits an assortment of items from the museum's collection representing them as a whole.[59]

Costumes and textiles

[edit]

The Patricia Harris Gallery of Costumes and Textiles holds about 200 artifacts from the ROM's textile and costume collections. These pieces, which range from the 1st century BC to the present day, are rotated frequently due to their fragility. Throughout time, textiles and fashion have been used to establish identity and allow inferences to be drawn about a culture's social customs, economy and survival. The gallery is devoted to showcasing transformations in textile design, manufacturing, and cultural relevance throughout the ages. Weaving, needlework, printed archeological textiles and silks are all located in this space.[60]

Interactive

[edit]The CIBC Discovery Gallery was designed to be a children's learning zone until its closure in 2023. It housed three main areas: In the Earth, Around the World and Close to Home. The space was inspired by the ROM's collections and enabled children to participate in interactive activities involving touchable artifacts and specimens, costumes, digging for dinosaur bones and examining fossils and meteorites. There was also a special area for preschoolers.[61]

The Patrick and Barbara Keenan Family Gallery of Hands-On Biodiversity introduces visitors to the complicated relationships, which occur among all living things in a fun and interactive space. People of all ages can explore touchable specimens and interactive displays while gallery facilitators help visitors discover the living world around them. Mossy frogs, a touchable shark jaw, snakeskin, and a replica fox's den are some of the objects that connect young visitors to the diversity and interdependence of plants and animals.[62]

Institute for Contemporary Culture

[edit]

The Roloff Beny Gallery of the Institute for Contemporary Culture (ICC) hosts the Royal Ontario Museum's contemporary art exhibitions.[63] This high-ceilinged multimedia gallery of approximately 6,000 sq ft (600 m2) serves as the ICC's main exhibition space, typically featuring exhibits that tie in contemporary culture and events, with the museum's natural and world collection.[64] The gallery has featured exhibitions on fashion photography,[65] street art,[66] modern Chinese urban design and architecture,[67] and contemporary Japanese art.[68] In 2018, it exhibited Here We Are: Black Canadian Contemporary Art, featuring Black Canadian artists such as Sandra Brewster, Michèle Pearson Clarke, Sylvia D. Hamilton, Bushra Junaid, Charmaine Lurch, and Esmaa Mohamoud.[69]

Natural history

[edit]

The natural history galleries are all gathered on the second floor of the museum, containing collections and examples of various specimens such as bats, birds and dinosaurs.

Nature and animals

[edit]

The Life in Crisis: Schad Gallery of Biodiversity, designed by Reich+Petch and opened in late 2009, features endangered species, including specimens of a polar bear, a giant panda, a white rhinoceros, a Burmese python, Canadian coral, a leatherback sea turtle, a coelacanth, a Rafflesia flower and many other rare species. Included among these specimens is Bull, a southern white rhinoceros that became a famous conservation success story for his species.[70] There are also recently extinct species displayed, including specimens of a passenger pigeon and a great auk, as well as skeletons of a dodo and a moa with a specimen of a moa egg, an elephant bird egg, and many other recently extinct species. The gallery presents the need to protect the natural environment and the need to educate the public about the main causes of extinction—overhunting, habitat destruction, and climate change. In September 2009, the gallery received an Award of Excellence by the Association of Registered Interior Designers of Ontario.[71] In addition to showcasing the museum's natural collection, the Schad Gallery also aims to promote the conservation of Earth's biodiversity.

The Life in Crisis gallery is organized into three zones exploring the central themes: Life is Diverse, Life is interconnected, and Life is at Risk. Anthony Reich, principal at Reich+Petch, called biodiversity "a big subject that's become more relevant to everybody. The challenge was how to tell this big story in a 10,000-square-foot (900 m2) space. We decided to design a dynamic, immersive experience with three core themes that hopefully will make a lasting impression on visitors."[72]

The Tallgrass Prairies and Savannas is a part of the gallery that features one of the most endangered and diverse habitats in Ontario. The display features examples of the regions and the efforts by the Ontario Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry to maintain and restore the tallgrass prairies and savannas.

The Gallery of Birds has on display many bird specimens from past centuries. The Gallery of Birds is dominated by the broad "Birds in flight" display where stuffed birds are enclosed in a glass display for visitors to experience. Dioramas allow visitors to learn about the many bird species and how environmental and habitual changes have put bird species in danger of extinction. Pull-out drawers let visitors examine eggs, feathers, footprints and nests more closely.[73] The gallery included exhibits of other extinct species such as the passenger pigeon. These exhibits were later moved to the Schad Gallery.

The Royal Ontario Museum purchased a beached blue whale off the coast of Newfoundland at Trout River and displayed its skeleton and heart as a ROM-original travelling exhibit until 4 September 2017.[74][75]

The Bat Cave is an immersive experience for visitors that presents over 20 bats and 800 models in a recreated habitat, with accompanying educational panels and video.[76] Originally opened in 1988, the bat cave reopened on 27 February 2010 after extensive renovations.[77] The 1,700-square-foot (160 m2) exhibit most notably includes a recreation of St. Clair Cave located in Saint Catherine Parish of central Jamaica. The original cave was formed by an underground river that flowed 30 metres (98 ft) below ground through the limestone and was three kilometres long. This cave was then recreated in the museum based on ROM fieldwork conducted in Jamaica in 1984.[78] A large amount of bat research has been conducted with support from the ROM. In 2011, the ROM hosted a "bat workshop" connected with the 41st Annual North American Symposium on Bat Research.[79]

Earth and space

[edit]

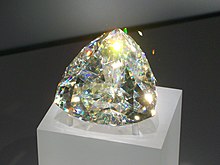

The Teck Suite of Galleries: Earth's Treasures features almost 3,000 specimens of minerals, gems, meteorites and rocks ranging from 4.5 billion years ago to the present. These items were found in many different locations including the Earth, Moon and beyond, and represent the Earth's dynamic geological environment.[80] Notable specimens at the Teck Suite of Galleries include fragments of the Tagish Lake meteorite.[81] The Light of the Desert, the world's largest faceted cerussite, is another notable piece displayed in the gallery.[82]

Galleries that are a part of the Teck Suite of Galleries include the Barrick Gold Corporation Gallery, the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame Gallery, the Gallery of Gems and Gold and the Vale Gallery of Minerals.[80]

Fossils and evolution

[edit]

The Reed Gallery of the Age of Mammals explores the rise of mammals through the Cenozoic Era that followed the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. There are over 400 specimens from North America and South America in addition to 30 fossil skeletons of extinct mammals.[83] The gallery's entrance begins with mammals that arose shortly after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. A highlight of this gallery is the sabre-toothed nimravid Dinictis.

The James and Louise Temerty Galleries of the Age of Dinosaurs and Gallery of the Age of Mammals feature many examples of complete non-avian dinosaur skeletons, as well as those of early birds, reptiles, mammals and marine animals ranging from the Jurassic to Cretaceous periods. The highlight of the exhibit is Gordo, one of the most complete examples of the Barosaurus in North America and the largest dinosaur on display in Canada.[84]

The Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life opened in 2021 in the former Peter F. Bronfman Hall, and focuses on the evolution of life in the Paleozoic from billions of years ago up to the Late Triassic. It highlights many fossil sites and collections from Canada, such as the Burgess Shale in British Columbia and Mistaken Point in Newfoundland and Labrador. The gallery is divided into six sections: "A Very Long Beginning" (Precambrian), "The Origin of Animals" (Cambrian Explosion), "The Bustling Seas" (Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian), "The Green Earth" (Devonian and Carboniferous, including both the Mississippian and the Pennsylvanian), "Before the Great Dying" (Permian) and "Dawn of a New Era" (Triassic).[85] Notable specimens include the Burgess Shale, orthocones and sea scorpions and other fossils from Ontario and the holotype of Dimetrodon borealis.[86]

The ROM also has a Zuul crurivastator skeleton from the Judith River Formation in Montana in its dinosaur collection, which is one of the most complete examples of an ankylosaurid specimen ever found.[87]

World culture

[edit]The world culture galleries display a wide variety of objects from around the world. These range from Stone Age implements from China and Africa to 20th-century art and design.[88] In July 2011, the museum added to this collection when a number of new permanent galleries were unveiled. Both the Government of Canada and the Royal Ontario Museum committed $2.75 million toward the project.[89] The galleries are located on the first, third and fourth levels of the museum.

Africa, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific

[edit]

The Shreyas and Mina Ajmera Gallery of Africa, the Americas and Asia–Pacific features a collection of 1,400 artifacts that reflect the artistic and cultural traditions of the indigenous peoples from four different geographical areas: Africa, the American continents, the Asia–Pacific region and Oceania. On display are objects such as ceremonial masks, ceramics, and a shrunken head.[90]

South Asia and Middle East

[edit]The Sir Christopher Ondaatje South Asian Gallery holds a diverse collection of objects such as decorative art, armour and sculptures that represents the culture of Indian subcontinent. The gallery has approximately 350 objects that represent over 5,000 years of history. Due to the wide range of history and cultures on display, the gallery is split into numerous different sections—the "Material Remains", "Imagining the Buddha", "Visualizing Divinity", "Passage to Enlightenment", "Courtly Culture", "Cultural Exchange" and "Home and the World".[91] In this gallery, visitors can find the (Untitled) Blue Lady sculpture by Mumbai-based artist Navjot Altaf.[92]

The Wirth Gallery of the Middle East explores civilizations from the Palaeolithic Age to 1900 AD found within the Fertile Crescent, which stretches from the Eastern Mediterranean and Persia (Iran) and Mesopotamia (Iraq) to the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant (Lebanon). The over 1,000 artifacts relate to the writing, technology, spirituality, everyday life and warfare of the ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. These Mesopotamian civilizations made major advances in writing, mathematics, law, medicine and religion, which are represented throughout the gallery.[93] Pieces from the museum's collection that are featured at the Wirth Gallery of the Middle East include plastered human skulls made in the Levant c. 8000 BC.[94] Another notable piece in the gallery is the Striding Lion, a wall relief from the throne room of Nebuchadnezzar II's palace in Babylon.[95]

Mediterranean

[edit]The Eaton Gallery of Rome is home to a millennium of ancient Roman culture. It has the largest collection of classical antiquities in Canada, displaying more than 500 objects that range from marble or painted portraits of historical figures to Roman jewellery. The gallery also features the Bratty Exhibit of Etruria that sheds some light on the Etruscans, a neighbouring civilization that was later absorbed by the expanding Rome.[96]

The Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Rome and the Near East depicts the lifestyle and culture of societies under Roman rule and their influence in the Near East.[97] The same space holds the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Byzantium, covering the history of the Byzantine Empire from AD 330 to 1453, during which crucial changes took place in early eastern Christianity. There are over 230 artifacts that relate to the dedication of Constantinople,[98] the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Medieval Crusades and the conquest by the Ottoman Turks—items such as jewellery, glasswork and coins help to illustrate the vast history of modern-day Istanbul.[98]

The A. G. Leventis Foundation Gallery of Ancient Cyprus houses roughly 300 artifacts, focusing on the art created in Cyprus between 2200 and 30 BC. The gallery is divided into five sections: "Cyprus and Commerce", "Ancient Cypriot Pottery Types", "Sculptures", "Ancient Cyprus at a Glance" and "Art & Society: Interpretations". The collection includes a reconstructed open-air sanctuary and a rare bronze relief statue of a man carrying a large copper ingot.[99]

The Gallery of Africa: Egypt focuses on the life (and the afterlife) of Ancient Egyptians. It includes a wide range of artifacts, ranging from agricultural implements, jewellery, cosmetics, funerary furnishings and more. The exhibit includes a number of mummy cases, including the fine gilded and painted sarcophagus and mummy of Djedmaatesankh, who was a female musician at the temple of Amun-Re in Thebes; and the mummy of Antjau, who is thought to have been a wealthy landowner.[100] Other items featured in the gallery include the Book of the Dead of Amen-em-hat, a 7-metre (23 ft) long scroll from circa 320 BC and the Bust of Cleopatra from c. 47 BC to 30 BC.[101][102] The Statue of Sekhmet can also be viewed at the gallery. Depicting Sekhmet, one of ancient Egypt's oldest deities, the item dates back to c. 1390–1325 BC.[103]

The Galleries of Africa: Nubia feature a collection of objects that explore the once-flourishing civilization of Nubia in modern-day Sudan. The Nubians were the first urban literate society in Africa south of the Sahara and were Egypt's main rival.[104]

The Gallery of the Bronze Age Aegean features over 100 objects that include examples from the Cycladic, Minoan, Mycenaean and Geometric periods of Ancient Greece. The collection ranges in age from 3200 BC to 700 BC and contains a variety of objects that include a marble head of a female figure and a glass necklace.[105]

The Gallery of Greece has a collection of 1,500 artifacts that span the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods. The collection consists of items such as sculptures of gods, armour and a coin collection.[106]

Canadian

[edit]

The Daphne Cockwell Gallery of Canada: First Peoples provides a look inside the culture of Canada's earliest societies: the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada. The gallery contains more than 1,000 artifacts that help to reveal the economic and social forces that have influenced Native art.[107][108][109]

The Royal Ontario Museum holds a major but little-known collection of Northwest Coast native art and artifacts acquired by the Reverend Dr. Richard Whitfield Large at Bella Bella, British Columbia, between 1899 and 1906 known as the "R. W. Large Collection". Although the collection is one of the most important Heiltsuk collections in existence because of its unique documentation, there has never been a comprehensive study of it.[110] Subject of the book Bella Bella: A Season of Heiltsuk Art, the collection was also part of the Kaxlaya Gvilas (Heiltsuk) exhibit put together collaboratively with the Heiltsuk Nation and the University of British Columbia.

There is also a rotating display of contemporary Native art, an area dedicated to the works of pioneer artist Paul Kane and a theatre devoted to traditional storytelling.[111] Just outside this gallery, the central staircase winds around the Nisga'a and Haida Crest Poles.[112]

The Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada was located on the Weston Family Wing, displaying collections of early Canadian memorabilia, the majority of which is historical decorative and pictorial arts, but also included a number of historical artifacts among other things. The gallery had approximately 560 artifacts on display and covers the period from early European settlement to the beginning of the modern industrial era.[113] The displays are split up into sections to display the strength and weaknesses of the collections reflect the French and British cultural heritage of Canada.[114] A notable item from the museum's collection that was featured at the Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada include The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West.[115] It closed in 2022.

East Asian

[edit]The Chinese Galleries comprise four sections: the Bishop White Gallery of Chinese Temple Art, the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of China, the Matthews Family Court of Chinese Sculpture and the ROM Gallery of Chinese Architecture.

The Bishop White Gallery of Chinese Temple Art gallery contains three of the world's best-preserved temple wall paintings from the Yuan dynasty (AD 1271–1386) and a number of wooden sculptures depicting various bodhisattvas from the 12th to 15th centuries.[116] Chinese temple wall paintings featured in this gallery include the Homage to the Highest Power, a Daoist wall painting dating to circa 1300 and Paradise of Maitreya, another Chinese wall temple painting from 1298.[117][118]

The Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of China consists of approximately 2,500 objects spanning almost 7,000 years of Chinese history. The gallery is divided into five sections: the "T. T. Tsui Exhibit of Prehistory and Bronze Age"; the "Qin and Han Dynasties"; the "Michael C. K. Lo Exhibition of North, South, Sui and Tang"; the "Song, Yuan and Frontier Dynasties"; and the "Ming and Qing Dynasties". Each section focuses on a different period of Chinese history, displaying objects ranging from jade discs to pieces of furniture.[119]

The Matthews Family Court of Chinese Sculpture has a wide variety of sculptures that span 2,000 years of Chinese sculptural art. It also displays a number of smaller objects that explore the development of religions in China from the 3rd to 19th centuries AD.[120] The gallery features several notable items from the museum's collection, including Wei Bin's Temple Bell, a ceremonial bell crafted in 1518, and the companion statues of Kashyapa and Ananda, two statues that originate from the Tang dynasty.[121][122] The gallery also features one of the Yixian glazed pottery luohans, a glazed sculpture that dates to the 11th century AD.[123]

The ROM Gallery of Chinese Architecture houses one of the largest collections of Chinese architectural artifacts outside of China and is the first gallery of Chinese architecture in North America. Artifacts held in the gallery include the Tomb of General Zu Dashou. The tomb includes an assortment of related artifacts, including the altar, stone burial mound and archway.[124] The gallery holds some spectacular exhibits such as a reconstruction of an Imperial Palace building from Beijing's Forbidden City and a Ming-era tomb complex.[125] It also holds ink rubbings from Ming-era steles originally located by a synagogue in Kaifeng in Henan province.

The Gallery of Korea is the only permanent gallery of Korean art in Canada, showcasing approximately 260 items from the Korean peninsula.[126] Furniture, ceramics, metalwork, printing technology, painting and decorative arts, dating from the 3rd to 20th centuries AD, illustrate the many accomplishments to Korean culture. The influence of Buddhism on Korean culture is portrayed with two statues, the first being a śarīra casket, which originated in India and were made to enshrine the remains of a Buddha or enlightened masters[127] and the second of a tomb guardian.

The Herman Herzog Levy Gallery is the primary venue for East Asian exhibitions visiting the museum.[128] The Portrait of Namjar was previously displayed in the gallery, although it was later removed and taken to storage.[129]

The museum also formerly held the Prince Takamado Gallery of Japan, which contained the largest collection of Japanese artworks in Canada, featuring a rotating display of ukiyo-e prints and the only tea master collection in North America. Notable pieces of Japanese art featured in the Prince Takamado Gallery of Japan included Fan print with two bugaku dancers and Unit 88-9.[130][131] The gallery was split into a number of different sections, each home to the collection of objects that the name suggests: the "Toyota Canada Inc. Exhibit of Ukiyo-e Pictures", the "Sony Exhibit of Painting", the "Canon Canada Inc. Samurai Exhibit", the "Mitsui and Co. Canada Tea Ceremony Exhibit", the "Maple Leaf Foods Exhibit of Lacquers" and the "Linamar Corporation Exhibit of Ceramics". The gallery was named in honour of the late Japanese Prince Takamado (also known as Norihito), who spent several years at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario.[132]

European

[edit]

The Samuel European Galleries have over 4,600 objects on display that chronicle the development of decorative and other arts in Europe from the Middle Ages to the 20th century.[133] The period rooms depict the development of decorative arts in Central and Western Europe by showcasing changes in style during the Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassical and Victorian periods. Other specialized collections relating to Culture and Context, Judaica, Art Deco and Arms and Armour are also displayed.[134] At the Samuel European Galleries is the Earl of Pembroke's Armour. Dating from 1550 to 1570, the armour was crafted for William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke.[135] Another notable piece from the museum's European collection is the Otho tazza.[136] The piece was one of 12 tazzas that made up the Aldobrandini Tazze, a set of Renaissance-era cups that featured the first 12 Roman emperors whose lives are described in the AD 121 publication The Twelve Caesars.

Accessibility

[edit]

The ROM provides accessibility promgrams and services for a wide range of communities in English and French.[137] These include:.[138]

- Tactile tours[139]

- An audio description program that provides descriptive narration for people who are blind or have low vision

- Tactile books featuring braille, raised line graphics, large print and colour pictures

- Large-print floor plans[139]

- Large-print guides

- Hands-on galleries

- Gallery interpreters that provide visitors with active exploration activities

- American Sign Language interpretation, tours and video podcasts

- Interactive touch screens

- A hearing loop system

- Assistive communication technology (Ubi-Duo), which allows real-time communication between a deaf visitor and staff members

Community access network

[edit]In 2008, the Royal Ontario Museum Community Access Network was created to make the ROM more accessible to a variety of communities. it provides free general admission tickets to participating community and charitable organizations. Each year, thousands of general admission tickets are distributed to these communities.[138] It tries to eliminate barriers that might stand between these communities and the museum. Since 2008, it has become a larger community initiative that seeks to enable learning experiences for visitors and organizations. A main goal of the program is to give the museum the power to engage, share and inspire a greater diversity of visitors by trying to break through economic and social barriers.[138] Partners include United Way of Greater Toronto, Boys & Girls Clubs of Canada, the Hospital for Sick Children and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).[140]

In popular culture

[edit]The 2000 novel Calculating God by Canadian science fiction author Robert J. Sawyer is mainly set in the ROM. The novel received nominations for both the Hugo and John W. Campbell Memorial Awards in 2001.[141] In the novel Bugs Potter Live at Nickaninny by Canadian children's fiction author Gordon Korman, one of the primary characters searching for the lost Naka-mee-chee (fictional) tribe was from the ROM. A large part of Life Before Man, a 1979 novel by Canadian writer Margaret Atwood, takes place in ROM. Three of the four main characters of the novel work there. The museum is described in the novel in great detail, including the dinosaur gallery with its exhibits, contemporary to the time when the novel takes place. The novel was a finalist for the Governor General's Award.

The museum was also filmed in several television shows. It was featured in Zoboomafoo, an American-Canadian children's television series in the season 1 episode "Dinosaurs", where the Kratt brothers (Chris and Martin) were invited to see the museum's dinosaur bones. The museum appeared as itself in the Canadian police procedural television series Flashpoint for an episode of the third season and the Canadian historical detective series Frankie Drake Mysteries in the season 2 episode "The Old Switcheroo". The Crystal was featured in the pilot of American science-fiction television series Fringe as a company headquarters and the season 2 episode "Shiizakana" of American television series Hannibal as a fossil exhibit.[142]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Dickson, Lovat (1986). The Museum Makers: the Story of the Royal Ontario Museum. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7441-3.

- Sabatino, Michelangelo; Windsor Liscombe, Rhodri (2015). Canada: Modern Architectures in History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-7802-3679-7.

- Shaw, Roberta L.; Grzymski, Krzysztof (1994). Galleries of the Royal Ontario Museum: Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Royal Ontario Museum. ISBN 0-88854-411-1.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The Royal Ontario Museum Draws Highest Attendance Numbers in its History" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ "ROM Announces Record-Breaking 1.35 Million Visitors Annual Attendance" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2017 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ Dickson 1986.

- ^ Jamie, Bradburn (9 July 2011). "Historicist: A Handbook to the Royal Ontario Museum, 1956". torontoist.com. Torontoist. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "ROM Trustees". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

The Royal Ontario Museum is an agency of the Government of Ontario.

- ^ a b "Collections and Research". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum Burgess Shale Expeditions (1975-ongoing)". burgess-shale.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b The Royal Ontario Museum Act, S.O. 1912, c. 80

- ^ a b c d Siddiqui, Norman. "Our History". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ "History of the Royal Ontario Museum" (PDF). rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ For the history of the archaeological and ethnographic collection of the Normal School, later given to the ROM, see Gerald Killan, David Boyle: From Artisan to Archaeologist, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1983 and Michelle A Hamilton, Collections and Objections: Aboriginal Material Culture in Southern Ontario, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010.

- ^ a b Dickson 1986, p. 88.

- ^ a b "Our History". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ The Royal Ontario Museum Act, 1947, S.O. 1947, c. 96

- ^ The Royal Ontario Museum Act, 1968, S.O. 1968, c. 119

- ^ "ROM History" (PDF). Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Beeston, Laura (27 January 2017). "Petition launched to save McLaughlin Planetarium from demolition". The Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Chrissie (19 February 2009). "Royal Ontario Museum agrees to sell McLaughlin Planetarium site to University of Toronto". Daily Commercial News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "FAQs". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum Review". arc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 November 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2005.

- ^ Petersen, Klaus & Allan C. Hutchinson. "Interpreting Censorship in Canada", University of Toronto Press, 1999

- ^ a b c d Bringham, Russel; Matthews, Laura. "Royal Ontario Museum". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Renaissance ROM: Learn More". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Nuttall-Smith, Chris (22 January 2010). "Who can save the ROM this time?". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Renaissance ROM Fact Sheet" (PDF). rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Lostracco, Marc (31 May 2007). "Inside The ROM Crystal: A First Look". torontoist.com. Torontoist. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b "History of the Royal Ontario Museum" (PDF). rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Sold-Out "The Singular Event" Gala celebrates Opening of Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, June 1st" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2019 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ "Heritage Property Detail, Address: 100 QUEEN'S PARK". City of Toronto Heritage Property Register. City of Toronto. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ White, Craig (14 February 2024). "OpenROM: A Multimillion Dollar Valentine's Gift to Toronto". UrbanToronto. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ White, Craig (23 May 2024). "Architectural Plans Reveal the Details of the OpenROM Renovation". UrbanToronto. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "About Us: Our History". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ^ a b Sabatino & Windsor Liscombe 2015, p. 60.

- ^ "The Museum: Past, Present and Future, by Dr. James E. Cruise". Speeches.empireclub.org. Empire Club. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Heritage of the ROM". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 6 April 2004. Retrieved 10 November 2005.

- ^ a b c "New ROM rising". Beijing.gc.ca. Canadian Embassy Beijing. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ ROM Members' News, Winter 2005–6.

- ^ "J. N. L. Durand's ideal". Rotunda. Vol. 36–39. Royal Ontario Museum. 2003. p. 18.

- ^ Browne, Kelvin (2008). Bold Visions: the Architecture of the Royal Ontario Museum. Toronto, Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum News Release: Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 26 March 2012 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ Hume, Christopher (14 March 2014). "How the Royal Ontario Museum represents 100 years of architecture". The Star. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum". daniel-libeskind.com. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Libeskind, Daniel. "Prominent Poles". Angelfire.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum opens Michael Lee-Chin Crystal Today – June 2" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 2 June 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2019 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ Rochon, Lisa (2 June 2007). "Crystal scatters no light". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Hume, Christopher (5 July 2012). "Christopher Hume's list of the best unknown buildings in Toronto". The Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "ROM's Crystal makes list of world's ugliest buildings". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 23 August 2012. Archived from the original on 23 November 2009.

- ^ "ROM addition dubbed ugliest by Washington Post". CBC News. 28 December 2009.

- ^ Joey Slinger (3 May 2007). "It's okay to think it's ugly". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- ^ "Exhibition Spaces". www.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011.

- ^ "Thorsell Spirit House - Royal Ontario Museum". www.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Toronto Welcomes Michael Lee-Chin Crystal on its Opening Weekend" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 4 June 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2019 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ "Dawn of the Crystal Age". www.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011.

- ^ "Dining". www.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Leaks, woes a smudge on Crystal's sparkle". The Globe and Mail. 3 October 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A Crystal with its fair share of wrinkles". The Globe and Mail. 18 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Davidson, Kelly (11 April 2007). "Repairs at Denver Art Museum Set to Begin". Archrecord.construction.com. Architectural Record. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Guide Rating and Review: Large Museum Shops". Archaeology.about.com. 12 July 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Samuel Hall Currelly Gallery". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles & Costume". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "CIBC Discovery Gallery". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Patrick and Barbara Keenan Family Gallery of Hands-on Biodiversity". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Toronto Arts Online". torontoartsonline.org. Toronto Arts Online. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Interview of William Thorsell, Director of the Royal Ontario Museum". The Globe and Mail. [dead link]

- ^ Ignacio Villarreal. "The First Art Newspaper". Artdaily.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Housepaint Blog". Housepaint.typepad.com. 13 December 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "BlogTO". BlogTO. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Hiroshi Sugimoto". The Globe and Mail. [dead link]

- ^ "Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art". Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Images". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "2009 ARIDO awards honour Ontario's best interior designers". Cision. 25 September 2009.

- ^ "Reich + biodiversity + Petch". canadianinteriors.com. 1 September 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Gallery of Birds". Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Digging up bones: Royal Ontario Museum moves to next stage of blue whale project". CBC News. CBC.

- ^ "Researchers hope to learn secrets in blue whale bones". CBC News. CBC.

- ^ "The Bat Cave". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ "The ROM reopens the bat cave, accessed 15 October 2013". Toronto Star. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2013 – via thestar.com.

- ^ "The Bat Cave is back, accessed 15 October 2013" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2013 – via rom.on.ca.

- ^ "Bat Workshop:41st Annual North American Symposium on Bat Research, accessed 15 October 2013" (PDF). batcon.org. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Tech Suite of Galleries: Earth's Treasures". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Tagish Lake". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Cerussite, Light of the Desert". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Reed Gallery of the Age of Mammals". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Sibonney, Claire (12 December 2007). "Canadian museum unveils long, long-lost dinosaur". ca.reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life". Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Iris (9 December 2021). "ROM's New Gallery: Dawn of Life". Sing Tao Elitegen. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Zuul, Destroyer of Shins". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "World Cultures". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Federal Investment Creates New Permanent Galleries at the Royal Ontario Museum". Infrastructure Canada. Government of Canada. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Shreyas and Mina Ajmera Gallery of Africa, the Americas and Asia-Pacific". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Sir Christopher Ondaatje South Asian Gallery". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Iconic: Blue Lady (Video)". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "Wirth Gallery of the Middle East". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Plastered human skull". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Iconic: Striding Lion". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Eaton Gallery of Rome". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Rome and the Near East". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 28 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Byzantium". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "The A.G. Leventis Foundation Gallery of Ancient Cyprus". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Coffin and mummy of the lady Djedmaatesankh". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Book of the Dead fragment, Anubis". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Sculpture, probably of Cleopatra VII". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Statue of lion-headed goddess Sekhmet". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Galleries of Africa: Nubia". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Gallery of the Bronze Age Aegean". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Gallery of Greece". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Daphne Cockwell Gallery dedicated to First Peoples art & culture". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Critic, Murray Whyte Visual Arts (19 April 2018). "ROM's newly reopened Indigenous galleries 'a great beginning'". Toronto Star. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ "Royal Ontario Museum 'pauses' Indigenous gallery for consultations to change exhibits". The Globe and Mail. 9 November 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Black, Martha (1997). Bella Bella: A Season of Heiltsuk Art. Royal Ontario Museum. p. 2. ISBN 1-55054-556-6.

- ^ "Daphne Cockwell Gallery of Canada: First Peoples". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Iconic: Totem Poles (Video)". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Bishop White Gallery of Chinese Temple Art". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "The Paradise of Maitreya wall-painting". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Daoist wall painting "Homage to the Highest Power" (west wall)". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of China". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Matthews Family Court of Chinese Sculpture". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Temple bell of Wei Bin". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Figure of the monk Ananda". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Figure of a luohan". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Tomb mound of General Zu Dashou". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "ROM Gallery of Chinese Architecture". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Gallery of Korea". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Matthew (27 September 2008). "The Sarira Casket". Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Herman Herzog Levy Gallery". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Hanging scroll portrait of second-rank bodyguard Namjar". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Fan print with two Bugaku Dancers in landscape". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Unit 88-9". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Prince Takamado Gallery of Japan". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Samuel European Galleries". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Samuel European Galleries". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "Anime Cuirass, Small Garniture for Battle". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ ""The Aldobrandini Tazza" with a figure of the Roman Emperor Otho (Marcus Silvius Otho (32-69; reigned Jan 15, 69 - Apr. 16, 69)". collections.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Access Programs and Services". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Accessibility". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Royal Ontario Museum opens doors to new era of accessibility". Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Community Access Partners". rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "2001 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Movies Filmed at Royal Ontario Museum". MovieMaps. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

External links

[edit]- Royal Ontario Museum

- Crown corporations of Ontario

- Museums in Toronto

- Art museums and galleries in Ontario

- History museums in Ontario

- Natural history museums in Ontario

- Asian art museums in Canada

- Egyptological collections in Canada

- Museums of ancient Greece in Canada

- Museums of Ancient Near East in North America

- Museums of ancient Rome in Canada

- Organizations based in Canada with royal patronage

- Rotundas (architecture)

- Museums established in 1914

- 1914 establishments in Ontario

- Darling and Pearson buildings

- Daniel Libeskind buildings

- Art Deco architecture in Canada