Metoprolol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛˈtoʊproʊlɑːl/, /mɛtoʊˈproʊlɑːl/ |

| Trade names | Lopressor, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682864 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Beta blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% (single dose)[2] 70% (repeated administration)[3] |

| Protein binding | 12% |

| Metabolism | Liver via CYP2D6, CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 3–7 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.051.952 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H25NO3 |

| Molar mass | 267.369 g·mol−1 |

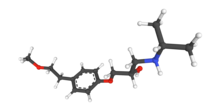

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 120 °C (248 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Metoprolol, sold under the brand name Lopressor among others, is a medication used to treat angina and a number of conditions involving an abnormally fast heart rate.[4] It is also used to prevent further heart problems after myocardial infarction and to prevent headaches in those with migraines.[4] It is a selective β1 receptor blocker medication.[4] It is taken by mouth or is given intravenously.[4]

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, feeling tired, feeling faint, and abdominal discomfort.[4] Large doses may cause serious toxicity.[5][6] Risk in pregnancy has not been ruled out.[4][7] It appears to be safe in breastfeeding.[8] The metabolism of metoprolol can vary widely among patients, often as a result of hepatic impairment[9] or CYP2D6 polymorphism.[10]

Metoprolol was first made in 1969, patented in 1970, and approved for medical use in 1978.[11][12][13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2022, it was the sixth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 65 million prescriptions.[15][16]

Medical uses

[edit]Metoprolol is used for a number of conditions, including angina, acute myocardial infarction, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and prevention of migraine headaches.[4] It is an adjunct in the treatment of hyperthyroidism.[17] Both oral and intravenous forms of metoprolol are available for administration.[18] The different salt versions of metoprolol – metoprolol tartrate and metoprolol succinate – are approved for different conditions and are not interchangeable.[19][20]

Off-label uses include supraventricular tachycardia and thyroid storm.[18]

Adverse effects

[edit]Adverse effects, especially with higher doses, include dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, diarrhea, unusual dreams, trouble sleeping, depression, and vision problems such as blurred vision or dry eyes.[21] β-blockers, including metoprolol, reduce salivary flow via inhibition of the direct sympathetic innervation of the salivary glands.[22][23] Metoprolol may also cause the hands and feet to feel cold.[24] Due to the high penetration across the blood–brain barrier, lipophilic beta blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol are more likely than other less lipophilic beta blockers to cause sleep disturbances such as insomnia, vivid dreams and nightmares.[25] Patients should be cautious while driving or operating machinery due to its potential to cause decreased alertness.[26][21]

There may also be an impact on blood sugar levels and it can potentially mask signs of low blood sugar.[21]

The safety of metoprolol during pregnancy is not fully established.[27][28]

Precautions

[edit]Metoprolol reduces long-term mortality and hospitalisation due to worsening heart failure.[29] A meta-analysis further supports reduced incidence of heart failure worsening in patients treated with beta-blockers compared to placebo.[30] However, in some circumstances, particularly when initiating metoprolol in patients with more symptomatic disease, an increased prevalence of hospitalisation and mortality has been reported within the first two months of starting.[31] Patients should monitor for swelling of extremities, fatigue, and shortness of breath.[32]

A Cochrane Review concluded that although metoprolol reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence, it is unclear whether the long-term benefits outweigh the risks.[33]

This medicine may cause changes in blood sugar levels or cover up signs of low blood sugar, such as a rapid pulse rate.[32] It also may cause some people to become less alert than they are normally, making it dangerous for them to drive or use machines.[32]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

[edit]Risk for the fetus has not been ruled out, per being rated pregnancy category C in Australia, meaning that it may be suspected of causing harmful effects on the human fetus (but no malformations).[7] It appears to be safe in breastfeeding.[8]

Overdose

[edit]Excessive doses of metoprolol can cause bradycardia, hypotension, metabolic acidosis, seizures, and cardiorespiratory arrest. Blood or plasma concentrations may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of overdose or poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma levels are usually less than 200 μg/L during therapeutic administration, but can range from 1–20 mg/L in overdose victims.[34][35][36]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Metoprolol is a beta blocker, or an antagonist of the β-adrenergic receptors. It is specifically a selective antagonist of the β1-adrenergic receptor and has no intrinsic sympathomimetic activity.[37]

Metoprolol exerts its effects by blocking the action of certain neurotransmitters, specifically adrenaline and noradrenaline. It does this by selectively binding to and antagonizing β-1 adrenergic receptors in the body. When adrenaline (epinephrine) or noradrenaline (norepinephrine) are released from nerve endings or secreted by the adrenal glands, they bind to β-1 adrenergic receptors found primarily in cardiac tissues such as the heart. This binding activates these receptors, leading to various physiological responses, including an increase in heart rate, force of contraction (inotropic effect), conduction speed through electrical pathways in the heart, and release of renin from the kidneys. Metoprolol competes with adrenaline and noradrenaline for binding sites on these β-1 receptors. By occupying these receptor sites without activating them, metoprolol blocks or inhibits their activation by endogenous catecholamines like adrenaline or noradrenaline.[38]

Metoprolol blocks β1-adrenergic receptors in heart muscle cells, thereby decreasing the slope of phase 4 in the nodal action potential (reducing Na+ uptake) and prolonging repolarization of phase 3 (slowing down K+ release).[39][non-primary source needed] It also suppresses the norepinephrine-induced increase in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ leak and the spontaneous SR Ca2+ release, which are the major triggers for atrial fibrillation.[39][non-primary source needed]

Through this mechanism of selective blockade at beta-(β)-1 receptors, metoprolol exerts the following effects:

- Heart rate reduction, i.e., decrease of the resting heart rate (negative chronotropic effect) and reduction of excessive elevations resulting from exercise or stress.[38]

- Reduction of the force of contraction, i.e., decrease in contractility (negative inotropic effect), which lessens how hard each heartbeat contracts.[38]

- Decrease in cardiac output, i.e., decrease in both heart rate and contractility within myocardium cells, where beta-(β)-1 is predominantly located, overall blood output per minute lowers called cardiac output/dysfunction, allowing decreased demands placed onto impaired hearts, reducing oxygen demand-supply mismatch.[38]

- Lowering of blood pressure.[38]

- Antiarrhythmic effects, such as supraventricular tachycardia prevention. Metoprolol also prevents electrical wave propagation.[38]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Metoprolol is mostly absorbed from the intestine with an absorption fraction of 0.95. The systemic bioavailability after oral administration is approximately 50%.[38] Less than 5% of an orally administered dose of metoprolol is excreted unchanged in urine; most of it is eliminated in metabolized form through feces via bile secretion into the intestines.[38]

Metoprolol undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver, mainly α-hydroxylation and O-demethylation through various cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP2D6 (primary), CYP3A4, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9. The primary metabolites formed are α-hydroxymetoprolol and O-demethylmetoprolol.[38][40][10]

Metoprolol is classified as a moderately lipophilic beta blocker.[37] More lipophilic beta blockers tend to cross the blood–brain barrier more readily, with greater potential for effects in the central nervous system as well as associated neuropsychiatric side effects.[37] Metoprolol binds mainly to human serum albumin with an unbound fraction of 0.88. It has a large volume of distribution at steady state (3.2 L/kg), indicating extensive distribution throughout the body.[38]

Chemistry

[edit]Metoprolol was synthesized and its activity discovered in 1969.[12] The specific agent in on-market formulations of metoprolol is either metoprolol tartrate or metoprolol succinate, where tartrate is an immediate-release formulation and the succinate is an extended-release formulation (with 100 mg metoprolol tartrate corresponding to 95 mg metoprolol succinate).[41]

Stereochemistry

[edit]This section needs expansion with: a statement from secondary sources of the importance/relevance of this information. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

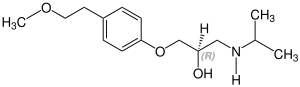

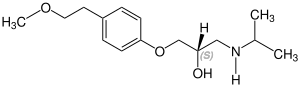

Metoprolol contains a stereocenter and consists of two enantiomers. This is a racemate, i.e. a 1:1 mixture of (R)- and the (S)-form:[42]

| Enantiomers of metoprolol | |

|---|---|

CAS-Number: 81024-43-3 |

CAS-Number: 81024-42-2 |

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]Metoprolol was approved for medical use in the United States in August 1978.[11]

Economics

[edit]In the 2000s, a lawsuit was brought against the manufacturers of Toprol XL (a time-release formula version of metoprolol) and its generic equivalent (metoprolol succinate) claiming that to increase profits, lower cost generic versions of Toprol XL were intentionally kept off the market. It alleged that the pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca AB, AstraZeneca LP, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, and Aktiebolaget Hassle violated antitrust and consumer protection law. In a settlement by the companies in 2012, without admission to the claims, they agreed to a settlement pay-out of US$ 11 million.[43][better source needed]

Sport

[edit]Because beta blockers can be used to reduce heart rate and minimize tremors, which can enhance performance in sports such as archery,[44][45] metoprolol is banned by the world anti-doping agency in some sports.[45]

References

[edit]- ^ "Lopressor Product information". Health Canada. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "Metolar 25/50 (metoprolol tartrate) tablet" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Jasek W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 916–919. ISBN 978-3852001814.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Metoprolol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Pillay VV (2012). "Diuretics, Antihypertensives, and Antiarrhythmics". Modern Medical Toxicology. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 303. ISBN 978-9350259658. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

- ^ Marx JA (2014). "Chapter 152: Cardiovascular Drugs". Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1455706051.

- ^ a b "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. p. 684. ISBN 978-0781728454. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

- ^ Regårdh CG, Jordö L, Ervik M, Lundborg P, Olsson R, Rönn O (1981). "Pharmacokinetics of metoprolol in patients with hepatic cirrhosis". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 6 (5): 375–388. doi:10.2165/00003088-198106050-00004. PMID 7333059. S2CID 1042204.

- ^ a b Blake CM, Kharasch ED, Schwab M, Nagele P (September 2013). "A meta-analysis of CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotype and metoprolol pharmacokinetics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 94 (3): 394–399. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.96. PMC 3818912. PMID 23665868.

- ^ a b "Lopressor: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b Carlsson B, ed. (1997). Technological systems and industrial dynamics. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. p. 106. ISBN 978-0792399728. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 461. ISBN 978-3527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Metoprolol Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013–2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Geffner DL, Hershman JM (July 1992). "Beta-adrenergic blockade for the treatment of hyperthyroidism". The American Journal of Medicine. 93 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90681-Z. PMID 1352658.

- ^ a b Morris J, Dunham A (2023). "Metoprolol". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30422518.

- ^ "Metoprolol vs Toprol-XL Comparison". Drugs.com. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Eske J (25 September 2019). "Metoprolol tartrate vs. succinate: Differences in uses and effects". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ a b c "Metoprolol (Oral Route)". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Costanzo L (2009). Physiology (3rd ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1416023203.

- ^ Turner MD (April 2016). "Hyposalivation and Xerostomia: Etiology, Complications, and Medical Management". Dental Clinics of North America. 60 (2): 435–443. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.003. PMID 27040294.

- ^ "Metoprolol". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010.

- ^ Cruickshank JM (2010). "Beta-blockers and heart failure". Indian Heart Journal. 62 (2): 101–110. PMID 21180298.

- ^ "Common questions about metoprolol". National Health Service (NHS). 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Metoprolol". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2006. PMID 30000215.

- ^ "Metoprolol". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 1994. PMID 35952115.

- ^ Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B, Wedel H, Waagstein F, Kjekshus J, et al. (March 2000). "Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). MERIT-HF Study Group". JAMA. 283 (10): 1295–1302. doi:10.1001/jama.283.10.1295. PMID 10714728.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Barron AJ, Zaman N, Cole GD, Wensel R, Okonko DO, Francis DP (October 2013). "Systematic review of genuine versus spurious side-effects of beta-blockers in heart failure using placebo control: recommendations for patient information". International Journal of Cardiology. 168 (4): 3572–3579. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.05.068. PMC 3819624. PMID 23796325.

- ^ Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML, Kjekshus J, Deedwania P, Gullestad L, Vitovec J, et al. (John Wikstrand; MERIT-HF Investigators) (March 2002). "Tolerability of beta-blocker initiation and titration in the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF)". Circulation. 105 (10): 1182–1188. doi:10.1161/hc1002.105180. PMID 11889011. S2CID 24119608.

- ^ a b c "Metoprolol (Oral Route) Precautions". Drug Information. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009.

- ^ Lafuente-Lafuente C, Valembois L, Bergmann J, Belmin J (2015). "Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005049. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005049.pub4. PMID 25820938.

- ^ Page C, Hacket LP, Isbister GK (September 2009). "The use of high-dose insulin-glucose euglycemia in beta-blocker overdose: a case report". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (3): 139–143. doi:10.1007/bf03161225. PMC 3550395. PMID 19655287.

- ^ Albers S, Elshoff JP, Völker C, Richter A, Läer S (April 2005). "HPLC quantification of metoprolol with solid-phase extraction for the drug monitoring of pediatric patients". Biomedical Chromatography. 19 (3): 202–207. doi:10.1002/bmc.436. PMID 15484221.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1023–1025.

- ^ a b c Cojocariu SA, Maștaleru A, Sascău RA, Stătescu C, Mitu F, Leon-Constantin MM (February 2021). "Neuropsychiatric Consequences of Lipophilic Beta-Blockers". Medicina. 57 (2): 155. doi:10.3390/medicina57020155. PMC 7914867. PMID 33572109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zamir A, Hussain I, Ur Rehman A, Ashraf W, Imran I, Saeed H, et al. (August 2022). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Metoprolol: A Systematic Review". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 61 (8): 1095–1114. doi:10.1007/s40262-022-01145-y. PMID 35764772. S2CID 250094483.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ a b Suita K, Fujita T, Hasegawa N, Cai W, Jin H, Hidaka Y, et al. (23 July 2015). "Norepinephrine-Induced Adrenergic Activation Strikingly Increased the Atrial Fibrillation Duration through β1- and α1-Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated Signaling in Mice". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0133664. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033664S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133664. PMC 4512675. PMID 26203906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Swaisland HC, Ranson M, Smith RP, Leadbetter J, Laight A, McKillop D, et al. (2005). "Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of gefitinib with rifampicin, itraconazole and metoprolol". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 44 (10): 1067–1081. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544100-00005. PMID 16176119. S2CID 1570605.

- ^ Cupp M (2009). "Alternatives for Metoprolol Succinate" (PDF). Pharmacist's Letter / Prescriber's Letter. 25 (250302). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Rote Liste Service GmbH (Hrsg.): Rote Liste 2017 – Arzneimittelverzeichnis für Deutschland (einschließlich EU-Zulassungen und bestimmter Medizinprodukte). Rote Liste Service GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, 2017, Aufl. 57, ISBN 978-3946057109, S. 200.

- ^ "$11 Million Settlement Reached in Lawsuit Involving the Heart Medication, Toprol XL, and its generic equivalent, metoprolol succinate". www.prnewswire.com (Press release).

- ^ Hughes D (October 2015). "The World Anti-Doping Code in sport: Update for 2015". Australian Prescriber. 38 (5): 167–170. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2015.059. PMC 4657305. PMID 26648655.

- ^ a b "The Prohibited List". World Anti Doping Agency. 3 January 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Dean L (2017). "Metoprolol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520381. Bookshelf ID: NBK425389.