Merovingian illumination

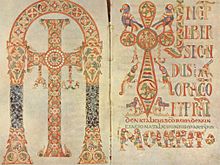

Merovingian illumination is the term for the continental Frankish style of illumination in the late seventh and eight centuries, named for the Merovingian dynasty. Ornamental in form, the style consists of initials constructed from lines and circles based on Late Antique illumination, title pages with arcades and crucifixes. Figural images were almost totally absent. From the eight century, zoomorphic decoration began to appear and become so dominant that in some manuscripts from Chelles whole pages are made up of letters formed from animals. Unlike the contemporary Insular illumination with its rampant decoration, the Merovingian style aims for a clean page.

One of the oldest and most productive scriptoria was Luxeuil Abbey, founded by the Irish monk Columbanus in 590 and destroyed in 732. Corbie Abbey, founded in 662, developed its own version of the style, while Chelles and Laon were further centres. From the middle of the eighth century, Merovingian illumination was strongly influenced by insular illumination. An evangeliary from Echternach (Trier, Dombibliothek, Cod. 61 olim 134.) indicates that it came into the abbey as the collaborative work of Irish and Merovingian scribes. The foundation of Willibrord strongly influenced continental illumination and led to the brought Irish culture into the Merovingian realm.

Historical context

[edit]

The Merovingian dynasty was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751.[1] They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gaulish Romans under their rule. They conquered most of Gaul, defeating the Visigoths (507) and the Burgundians (534), and also extended their rule into Raetia (537). In Germania, the Alemanni, Bavarii and Saxons accepted their lordship. The Merovingian realm was the largest and most powerful of the states of western Europe following the breaking up of the empire of Theodoric the Great.

The dynastic name, medieval Latin Merovingi or Merohingii ("sons of Merovech"), derives from an unattested Frankish form, akin to the attested Old English Merewīowing,[2] with the final -ing being a typical Germanic patronymic suffix. The name derives from King Merovech, whom many legends surround. Unlike the Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies, the Merovingians never claimed descent from a god, nor is there evidence that they were regarded as sacred.

The Merovingians' long hair distinguished them among the Franks, who commonly cut their hair short. Contemporaries sometimes referred to them as the "long-haired kings" (Latin reges criniti). A Merovingian whose hair was cut could not rule, and a rival could be removed from the succession by being tonsured and sent to a monastery. The Merovingians also used a distinct name stock. One of their names, Clovis, evolved into Louis and remained common among French royalty down to the 19th century.

The first known Merovingian king was Childeric I (died 481). His son Clovis I (died 511) converted to Christianity, united the Franks and conquered most of Gaul. The Merovingians treated their kingdom as single yet divisible. Clovis's four sons divided the kingdom among themselves and it remained divided—with the exception of four short periods (558–61, 613–23, 629–34, 673–75)—down to 679. After that it was only divided again once (717–18). The main divisions of the kingdom were Austrasia, Neustria, Burgundy and Aquitaine.

During the final century of Merovingian rule, the kings were increasingly pushed into a ceremonial role. Actual power was increasingly in the hands of the mayor of the palace, the highest-ranking official under the king. In 656, the mayor Grimoald I tried to place his son Childebert on the throne in Austrasia. Grimoald was arrested and executed, but his son ruled until 662, when the Merovingian dynasty was restored. When King Theuderic IV died in 737, the mayor Charles Martel continued to rule the kingdoms without a king until his death in 741. The dynasty was restored again in 743, but in 751 Charles's son, Pepin the Short, deposed the last king, Childeric III, and had himself crowned, inaugurating the Carolingian dynasty.

Types

[edit]

The manuscripts produced at this time are essentially intended for the practice of worship within monasteries and not for the evangelization of the population. Gospel books are therefore rarer than missals, sacramentaries, lectionaries, etc., at least among illuminated manuscripts. The books of the Church Fathers were also of great privilege, such as the writings of Augustine or Gregory.[3]

Characteristics

[edit]Ornaments

[edit]The style of Merovingian illuminations is largely ornamental, and representations of the human figure are extremely rare and only occur at the end of the Merovingian period. Several typical types of ornament are found in Merovingian manuscripts.

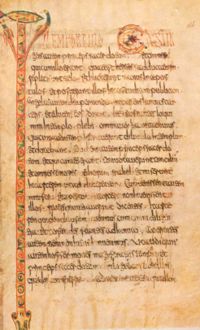

The manuscripts do not contain large initials occupying a full page, but the text generally begins with an integrated initial or a decorated title, accompanied by arches framing the text. The Gelasian sacramentary contains at the beginning of each part of the missal a large portico framing the text.[4][3]

Particular care is taken with the scribal work of the text. While Insular artists heavily ornamented entire pages of their manuscripts with interlacing motifs in freehand, the Merovingian artists systematically used the ruler and the compass to trace the initials. The initials and sometimes several whole words of the text were decorated with plant and zoomorphic motifs (especially birds and fish) which mingle with abstract geometric motifs. Gradually, these animals left their geometric form to take more and more a realistic appearance. In some manuscripts appear the first zoomorphic and anthropomorphic initials in the history of illumination. These are letters that do not serve as a framework for the representation of an animal or a human being, but which are constituted by one or more of these beings forming the letter or its various parts. For example, at f° 132 of the Gelasian Sacramentary, the letters of the word “NOVERIT” are made up of both birds and fish. The artist in charge of these decorations was generally the same scribe who copied the text.[5]

The almost ubiquitous Christian motif is the cross. It sometimes covers a full page, sometimes integrated into a carpet page, as in Irish manuscripts.[6]

First instance of human depiction

[edit]Human depictions appeared towards the end of this period, they are not strictly speaking historiated illuminations, that is to say representing a scene taken from the Bible or a historical scene. The first surviving manuscript to include human representations is the Sacramentary of Gellone. With portraits of evangelists found for the first time in the Gospel of Gundohinus.[3]

Influences

[edit]The Byzantine influence in particular is often noticed. Some historians have put forward the hypothesis that the Merovingian illuminators sometimes took as models motifs found on oriental fabrics having wrapped relics. The Sacramentary of Gellone, for example, seems in certain aspects very close to the Byzantine manuscripts.[7]

Several centers were also influenced by Insular illumination. Several abbeys, founded by abbots from Ireland or Northumbria, were places of production of manuscripts mixing the two styles and sometimes artists from the islands and the continent. This is particularly the case at the Abbey of Echternach, where the Trier Gospel Book was produced around 700–750. The style that developed there is sometimes referred to as Franco-Saxon.[8]

Centers of production

[edit]With a few exceptions, the precise localization of the place of production of the Merovingian manuscripts is not guaranteed and is sometimes called into question.

Laon

[edit]This episcopal see, founded by Remigius at the beginning of the sixth century, is a notable exception among others to the cultural decline of the cities. Always dominated by its bishops, Laon remained, during the Merovingian and Carolingian period, a living artistic and intellectual center, and in particular the Colombian abbey of Saint-Vincent.

Main manuscripts:

- Quaestiones in Heptateuchon of Saint Augustine (National Library of France).

- Codices 137 and 423 (Library of Laon).[9]

Luxeuil Monastery

[edit]

In 590, Columbanus founded the monastery of Luxeuil in the Vosges. The scriptorium of this abbey acquired a high reputation for Its quality a few decades later. Plundered and ravaged by the Saracens, who massacred all the monks, in 731 or 732, the abbey was relieved by Charlemagne who entrusted it to the Benedictines. The abbey gave its name to a particular script, without it being possible to say with certainty that it could have been created in its scriptorium. It is found in several manuscripts whose place of production remains controversial:

- In Epistolam Joannis ad Parthos tractatus decem, Augustine of Hippo, dated around 669, Pierpont Morgan Library (M.334).[10]

- The so-called Luxeuil Lectionary, National French Library, Lat. 9427.

- Missale Gothicum, sacramentary produced around 700.

- Vatican, Reg. Lat. 317. Codex Ragyntrudis, texts of the Church Fathers, Library of the Cathedral of Fulda (Hesse, Germany).

- Works of Saint Augustine, circa 730, currently at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel (Lower Saxony (Weissenburg 99), Germany).

Corbie Abbey

[edit]Located in the Somme, near Amiens, the abbey was founded by Balthild of Chelles. Manuscripts produced on site use less zoomorphic motifs but more ornaments such as the "bull's eye" (a circle with a dot in the middle). From the middle of the 8th century, we find more and more interlacing.[11]

Main manuscripts:

- Commentary on Ezekiel by Saint Gregory (2nd quarter of the 7th century. Saint Petersburg Library (Q.V.I.14).[12]

- Rule of Saint Basil, around 700. Book preserved in the Russian National Library in Saint Petersburg.

- Hexaemeron said of Ambrose,[13] 2nd half of the 8th century, National Library of France.

- A manuscript of The Mystical Exposition on the Song of Songs by Justus of Urgell, circa 700, Vallicelliane Library, Rome (B.62).

Chelles

[edit]Chelles, in Seine-et-Marne, was the seat of a Merovingian palace. In 584, Chilperic I was assassinated there on the orders of the mayor of the Landry palace, lover of Frédégonde, the king's own wife. A first abbey of nuns was founded by Clotilde in the sixth century. It was rebuilt in the 7th century by Bathilde, wife of Clovis II. The historian Bernard Bischoff has shown that nine nuns of this abbey, whose names are known, copied and illuminated at the end of the Merovingian era, three manuscripts for the archchaplain of Charlemagne, Bishop Hildebold of Cologne. These are Ms. 63, 65, 67, late 8th century, now in the library of Cologne Cathedral.

Saint-Denis Abbey

[edit]The scriptorium of the abbey of Saint-Denis, protected by Charles Martel and Pepin the Short, is, according to some historians, perhaps the place of production of one of the most famous Merovingian illuminated manuscripts: the Gelasian Sacramentary which keeps track transformations of the liturgy due to Gelasius. Vatican, Apostolic Library, Reg. Lat. 316.

Examples

[edit]| Image | Name | Date | Location, school | Contents, significance | Inventory number |

|

Sélestat Lectionary | c.700 | Humanist Library of Sélestat | ||

|

Gelasian Sacramentary | c.750 | Sacramentary | Rome, Vatican Library, Reg. Lat. 316 | |

|

c.750 | East West Francia (Burgundy?) | Bible | Autun, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms 2 | |

|

Gundohinus Gospels | 754/755 | Vosevio Abbey (location unknown), East West Francia, possibly Burgundy | Evangeliary | Autun, Bibliothèque Municipale. Ms 3 |

|

c.780 | Saint-Pierre de Flavigny (east West Francia) | Autun, Bibliothèque Municipale. Ms 5 | ||

|

Sacramentary of Gellone | End of the eighth century | Meaux | Sakramentar | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 12048 |

|

End of the eighth century | Burgundy | Evangeliary for the use of Saint-Pierre de Flavigny (Burgundy) | Autun, Bibliothèque Municipale. Ms 4 |

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Kunibert Bering: Kunst des frühen Mittelalters. 2nd revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-018169-0, (Kunst-Epochen. 2) (Reclams Universal-Bibliothek. 18169).

- Ernst Günther Grimme: Die Geschichte der abendländischen Buchmalerei. 3rd Edition. Köln, DuMont 1988. ISBN 3-7701-1076-5.

- Christine Jakobi-Mirwald: Das mittelalterliche Buch. Funktion und Ausstattung. Stuttgart, Reclam 2004. ISBN 978-3-15-018315-1, (Reclams Universal-Bibliothek 18315), (Besonders Kapitel Geschichte der europäischen Buchmalerei S. 222–278).

- Buchmalerei. In Severin Corsten / Günther Pflug / Friedrich Adolf Schmidt-Künsemüller (Edd.): Lexikon des Mittelalters 2: Bettlerwesen bis Codex von Valencia. Lizenzausgabe. Unveränderter Nachdruck der Studienausgabe 1999. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-22804-1, pp. 837–893, (Contributions by K. Bierbrauer, Ø. Hjort, O. Mazal, D. Thoss, G. Dogaer, J. Backhouse, G. Dalli Regoli, H. Künzl).

- Otto Pächt: Buchmalerei des Mittelalters. Eine Einführung. Edited by Dagmar Thoss. 5th Edition. Prestel, München 2004. ISBN 978-3-7913-2455-5.

- Ingo F. Walther / Norbert Wolf: Codices illustres. Die schönsten illuminierten Handschriften der Welt. Meisterwerke der Buchmalerei. 400 bis 1600. Taschen, Köln etc. 2005, ISBN 3-8228-4747-X.

References

[edit]- ^ Pfister, Christian (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–172.

- ^ Babcock, Philip (ed). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1993: 1415

- ^ a b c Nordenfalk, p.44

- ^ Patrick Périn, Encyclopædia Universalis, article « Mérovingiens / Art mérovingien ».

- ^ Nordenfalk, p.44-47 et 51

- ^ Nordenfalk, p.44-46

- ^ Nordenfalk, p.51

- ^ J.J.G. Carl Nordenfalk, Manuscrits Irlandais et Anglo-Saxons : L'enluminure dans les îles Britanniques de 600 à 800, Paris, éditions du Chêne, 1977, p.88

- ^ « Manuscrits de la bibliothèque de Laon »

- ^ Notice de la Morgan Lib.

- ^ Nordenfalk, p.52

- ^ Notice du manuscrit

- ^ L'Hexaemeron ou Ouvrage des six jours, est une œuvre de saint Basile (330-379) célèbre dans l'Antiquité ; Grégoire de Nysse (vers 330-vers 395 son frère, Grégoire de Nazianze (vers 330-vers 390) son ami et plusieurs autres, en ont fait le plus grand éloge. Saint Ambroise (vers 330/340-397) en a fait une traduction latine.