The Wire

The Wire is an American crime drama television series created and primarily written by American author and former police reporter David Simon for the cable network HBO. The series premiered on June 2, 2002, and ended on March 9, 2008, comprising 60 episodes over five seasons. The idea for the show started out as a police drama loosely based on the experiences of Simon's writing partner Ed Burns, a former homicide detective and public school teacher.[4]

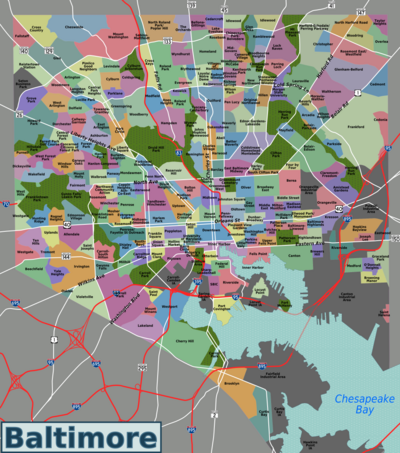

Set and produced in Baltimore, Maryland, The Wire introduces a different institution of the city and its relationship to law enforcement in each season while retaining characters and advancing storylines from previous seasons. The five subjects are, in chronological order; the illegal drug trade, the port system, the city government and bureaucracy, education and schools, and the print news medium. Simon chose to set the show in Baltimore because of his familiarity with the city.[4]

When the series first aired, the large cast consisted mainly of actors who were unknown to television audiences, as well as numerous real-life Baltimore and Maryland figures in guest and recurring roles. Simon has said that despite its framing as a crime drama, the show is "really about the American city, and about how we live together. It's about how institutions have an effect on individuals. Whether one is a cop, a longshoreman, a drug dealer, a politician, a judge or a lawyer, all are ultimately compromised and must contend with whatever institution to which they are committed."[5]

The Wire is lauded for its literary themes and its uncommonly accurate exploration of society, politics and urban life. Despite this, the series received only average ratings and never won any major television awards during its original run, but it is now widely regarded as one of the greatest television series of all time.[6]

Production

[edit]Conception

[edit]Simon has stated that he originally set out to create a police drama loosely based on the experiences of his writing partner Ed Burns, a former homicide detective and public school teacher who had worked with Simon on projects including The Corner (2000). Burns, when working on protracted investigations of violent drug dealers using surveillance technology, had often been frustrated by the bureaucracy of the Baltimore Police Department; Simon saw similarities with his own ordeals as a police reporter for The Baltimore Sun.

Simon chose to set the show in Baltimore because of his familiarity with the city. During his time as a writer and producer for the NBC program Homicide: Life on the Street, based on his book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (1991), also set in Baltimore, Simon had come into conflict with NBC network executives who were displeased by the show's pessimism. Simon wanted to avoid a repeat of these conflicts and chose to take The Wire to HBO, because of their working relationship from the miniseries The Corner. HBO was initially doubtful about including a police drama in its lineup but agreed to produce the pilot episode.[7][8] Simon approached the mayor of Baltimore, telling him that he wanted to give a bleak portrayal of certain aspects of the city; Simon was welcomed to work there again. He hoped the show would change the opinions of some viewers but said that it was unlikely to affect the issues it portrays.[7]

Casting

[edit]The casting of the show has been praised for avoiding big-name stars and using character actors who appear natural in their roles.[9] The looks of the cast as a whole have been described as defying TV expectations by presenting a true range of humanity on screen.[10] Many of the cast are black, consistent with the demographics of Baltimore.

Wendell Pierce, who plays Detective Bunk Moreland, was the first actor to be cast. Dominic West, who won the ostensible lead role of Detective Jimmy McNulty, sent in a tape he recorded the night before the audition's deadline of his playing out a scene by himself.[11] Lance Reddick received the role of Cedric Daniels after auditioning for the roles of Bunk and heroin addict Bubbles.[12] Michael K. Williams got the part of Omar Little after only a single audition.[13] Williams himself recommended Felicia Pearson for the role of Snoop after meeting her at a local Baltimore bar, shortly after she had served prison time for a second degree murder conviction.[14]

Several prominent real-life Baltimore figures, including former Maryland Governor Robert L. Ehrlich Jr.; Rev. Frank M. Reid III; radio personality Marc Steiner; former police chief and radio personality Ed Norris; Baltimore Sun reporter and editor David Ettlin; Howard County Executive Ken Ulman; and former mayor Kurt Schmoke have appeared in minor roles despite not being professional actors.[15][16]

"Little Melvin" Williams, a Baltimore drug lord arrested in the 1980s by an investigation that Burns had been part of, had a recurring role as a deacon beginning in the third season. Jay Landsman, a longtime police officer who inspired the character of the same name,[17] played Lieutenant Dennis Mello.[18] Baltimore police commander Gary D'Addario served as the series' technical advisor for the first two seasons[19][20] and had a recurring role as prosecutor Gary DiPasquale.[21] Simon shadowed D'Addario's shift when researching his book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets and both D'Addario and Landsman are subjects of the book.[22]

More than a dozen cast members previously appeared on HBO's first hour-long drama Oz. J. D. Williams, Seth Gilliam, Lance Reddick, and Reg E. Cathey were featured in very prominent roles on Oz, while a number of other notable stars of The Wire, including Wood Harris, Frankie Faison, John Doman, Clarke Peters, Domenick Lombardozzi, Michael Hyatt, Michael Potts, and Method Man, appeared in at least one episode of Oz.[23] Cast members Erik Dellums, Peter Gerety, Clark Johnson, Clayton LeBouef, Toni Lewis and Callie Thorne also appeared on Homicide: Life on the Street, the earlier and award-winning network television series also based on Simon's book; Lewis appeared on Oz as well. A number of cast members, as well as crew members, also appeared in the preceding HBO miniseries The Corner including Clarke Peters, Reg E. Cathey, Lance Reddick, Corey Parker Robinson, Robert F. Chew, Delaney Williams, and Benay Berger.

Crew

[edit]Alongside Simon, the show's creator, head writer, showrunner, and executive producer, much of the creative team behind The Wire were alumni of Homicide and Primetime Emmy Award-winning miniseries The Corner. The Corner veteran, Robert F. Colesberry, was executive producer for the first two seasons and directed the season 2 finale before dying from complications from heart surgery in 2004. He is credited by the rest of the creative team as having a large creative role as a producer, and Simon credits him for achieving the show's realistic visual feel.[5] He also had a small recurring role as Detective Ray Cole.[24] Colesberry's wife Karen L. Thorson joined him on the production staff.[19] A third producer on The Corner, Nina Kostroff Noble also stayed with the production staff for The Wire rounding out the initial four-person team.[19] Following Colesberry's death, she became the show's second executive producer alongside Simon.[25]

Stories for the show were often co-written by Burns, who also became a producer in the show's fourth season.[26] Other writers include three acclaimed crime fiction writers from outside of Baltimore: George Pelecanos from Washington, Richard Price from the Bronx and Dennis Lehane from Boston.[27] Reviewers drew comparisons between Price's works (particularly Clockers) and The Wire even before he joined.[28] In addition to writing, Pelecanos served as a producer for the third season.[29] Pelecanos has commented that he was attracted to the project because of the opportunity to work with Simon.[29]

Staff writer Rafael Alvarez penned several episodes' scripts, as well as the series guidebook The Wire: Truth Be Told. Alvarez is a colleague of Simon's from The Baltimore Sun and a Baltimore native with working experience in the port area.[30] Another city native and independent filmmaker, Joy Lusco, also wrote for the show in each of its first three seasons.[31] Baltimore Sun writer and political journalist William F. Zorzi joined the writing staff in the third season and brought a wealth of experience to the show's examination of Baltimore politics.[30]

Playwright and television writer/producer Eric Overmyer joined the crew of The Wire in the show's fourth season as a consulting producer and writer.[26] He had also previously worked on Homicide. Overmyer was brought into the full-time production staff to replace Pelecanos who scaled back his involvement to concentrate on his next book and worked on the fourth season solely as a writer.[32] Primetime Emmy Award winner, Homicide and The Corner, writer and college friend of Simon, David Mills also joined the writing staff in the fourth season.[26]

Directors include Homicide alumnus Clark Johnson,[33] who directed several acclaimed episodes of The Shield,[34] and Tim Van Patten, a Primetime Emmy Award winner who has worked on every season of The Sopranos. The directing has been praised for its uncomplicated and subtle style.[9] Following the death of Colesberry, director Joe Chappelle joined the production staff as a co-executive producer and continued to regularly direct episodes.[35]

Episode structure

[edit]Each episode begins with a cold open that seldom contains a dramatic juncture. The screen then fades or cuts to black while the intro music fades in. The show's opening title sequence then plays; a series of shots, mainly close-ups, concerning the show's subject matter that changes from season to season, separated by fast cutting (a technique rarely used in the show itself). The opening credits are superimposed on the sequence, and consist only of actors' names without identifying which actors play which roles. In addition, actors' faces are rarely seen in the title sequence.

At the end of the sequence, a quotation (epigraph) is shown on-screen that is spoken by a character during the episode. The three exceptions were the first season finale which uses the phrase "All in the game", attributed to "Traditional West Baltimore", a phrase used frequently throughout all five seasons including that episode; the fourth season finale which uses the words "If animal trapped call 410-844-6286" written on boarded up vacant homes attributed to "Baltimore, traditional" and the series finale, which started with a quote from H. L. Mencken that is shown on a wall at The Baltimore Sun in one scene, neither quote being spoken by a character. Progressive story arcs often unfold in different locations at the same time. Episodes rarely end with a cliffhanger, and close with a fade or cut to black with the closing music fading in.

When broadcast on HBO and on some international networks, the episodes are preceded by a recap of events that have a bearing upon the upcoming narrative, using clips from previous episodes.

Music

[edit]Rather than overlaying songs on the soundtrack, or employing a score, The Wire primarily uses pieces of music that emanate from a source within the scene, such as a jukebox or car radio. This kind of music is known as diegetic or source cue. This practice is rarely breached, notably for the end-of-season montages and occasionally with a brief overlap of the closing theme and the final shot.[36]

The opening theme is "Way Down in the Hole," a gospel-and-blues-inspired song, written by Tom Waits for his 1987 album Franks Wild Years. Each season uses a different recording and a different opening sequence, with the theme being performed by The Blind Boys of Alabama, Waits, The Neville Brothers, DoMaJe and Steve Earle. The season four version of "Way Down in the Hole" was arranged and recorded for the show and is performed by five Baltimore teenagers: Ivan Ashford, Markel Steele, Cameron Brown, Tariq Al-Sabir and Avery Bargasse.[37] Earle, who performed the fifth season version, is also a member of the cast, playing the recovering drug addict Walon.[38] The closing theme is "The Fall," composed by Blake Leyh, who is also the music supervisor of the show.

During season finales, a song is played before the closing scene in a montage showing the lives of the protagonists in the aftermath of the narrative. The first season montage is played over "Step by Step" by Jesse Winchester, the second "I Feel Alright" by Steve Earle, the third "Fast Train" written by Van Morrison and performed by Solomon Burke, the fourth "I Walk on Gilded Splinters" written by Dr. John and performed by Paul Weller and the fifth uses an extended version of "Way Down In The Hole" by the Blind Boys of Alabama, the same version of the song used as the opening theme for the first season.[28]

While the songs reflect the mood of the sequence, their lyrics are usually only loosely tied to the visual shots. In the commentary track to episode 37, "Mission Accomplished", executive producer David Simon said: "I hate it when somebody purposely tries to have the lyrics match the visual. It brutalizes the visual in a way to have the lyrics dead on point. ... Yet at the same time it can't be totally off point. It has to glance at what you're trying to say."[28]

Two soundtrack albums, called The Wire: And All the Pieces Matter—Five Years of Music from The Wire and Beyond Hamsterdam, were released on January 8, 2008, on Nonesuch Records.[39] The former features music from all five seasons of the series and the latter includes local Baltimore artists exclusively.[39]

Style

[edit]Realism

[edit]The writers strove to create a realistic vision of an American city based on their own experiences.[40] Simon, originally a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, spent a year researching a Baltimore homicide detective unit for his book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, where he met Burns. Burns served in the Baltimore Police Department for 20 years and later became a teacher in an inner-city school. The two of them spent a year researching the drug culture and poverty in Baltimore for their book The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood. Their combined experiences were used in many storylines of The Wire.

Central to the show's aim for realism was the creation of truthful characters. Simon has stated that most of them are composites of real-life Baltimore figures.[41] For instance, Donnie Andrews served as the main inspiration of Omar Little.[42] Martin O'Malley served as "one of the inspirations" for Tommy Carcetti.[43] The show often cast non-professional actors in minor roles, distinguishing itself from other television series by showing the "faces and voices of the real city" it depicts.[3] The writing also uses contemporary slang to enhance the immersive viewing experience.[3]

In distinguishing the police characters from other television detectives, Simon makes the point that even the best police of The Wire are motivated not by a desire to protect and serve, but by the intellectual vanity of believing they are smarter than the criminals they are chasing. While many of the police do exhibit altruistic qualities, many officers portrayed on the show are incompetent, brutal, self-aggrandizing, or hamstrung by bureaucracy and politics. The criminals are not always motivated by profit or a desire to harm others; many are trapped in their existence and all have human qualities. Even so, The Wire does not minimize or gloss over the horrific effects of their actions.[5]

The show is realistic in depicting the processes of both police work and criminal activity. There have even been reports of real-life criminals watching the show to learn how to counter police investigation techniques.[44][45] The fifth season portrayed a working newsroom at The Baltimore Sun and was described by Brian Lowry of Variety magazine in 2007 as the most realistic portrayal of the media in film and television.[46]

In a December 2006 Washington Post article, local black students said that the show had "hit a nerve" with the black community and that they themselves knew real-life counterparts of many of the characters. The article expressed great sadness at the toll drugs and violence are taking on the black community.[47]

Visual novel

[edit]Many important events occur off-camera and there is no artificial exposition in the form of voice-over or flashbacks, with the exceptions of two flashbacks – one at the end of the pilot episode that replays a moment from earlier in the same episode and one at the end of the fourth season finale that shows a short clip of a character tutoring his younger brother earlier in the season. Thus, the viewer needs to follow every conversation closely to understand the ongoing story arc and the relevance of each character to it. Salon has described the show as novelistic in structure, with a greater depth of writing and plotting than other crime shows.[27]

Each season of The Wire consists of 10 to 13 episodes that form several multi-layered narratives. Simon chose this structure with an eye towards long story arcs that draw in viewers, resulting in a more satisfying payoff. He uses the metaphor of a visual novel in several interviews,[7][48] describing each episode as a chapter, and has also commented that this allows a fuller exploration of the show's themes in time not spent on plot development.[5]

Social commentary

[edit]

Simon described the second season as "a meditation on the death of work and the betrayal of the American working class ... it is a deliberate argument that unencumbered capitalism is not a substitute for social policy; that on its own, without a social compact, raw capitalism is destined to serve the few at the expense of the many."[41] He added that season 3 "reflects on the nature of reform and reformers, and whether there is any possibility that political processes, long calcified, can mitigate against the forces currently arrayed against individuals." The third season is also an allegory that draws explicit parallels between the Iraq War and drug prohibition,[41] which in Simon's view has failed in its aims[45] and has become a war against America's underclass.[49] This is portrayed by Major Colvin, imparting to Carver his view that policing has been allowed to become a war and thus will never succeed in its aims.[citation needed]

Writer Ed Burns, who worked as a public school teacher after retiring from the Baltimore police force shortly before going to work with Simon, has called education the theme of the fourth season. Rather than focusing solely on the school system, the fourth season looks at schools as a porous part of the community that are affected by problems outside of their boundaries. Burns states that education comes from many sources other than schools and that children can be educated by other means, including contact with the drug dealers they work for.[50] Burns and Simon see the theme as an opportunity to explore how individuals end up like the show's criminal characters and to dramatize the notion that hard work is not always justly rewarded.[51]

Themes

[edit]Institutional dysfunction

[edit]Simon has identified the organizations featured in the show—the Baltimore Police Department, City Hall, the Baltimore public school system, the Barksdale drug trafficking operation, The Baltimore Sun, and the stevedores' union—as comparable institutions. All are dysfunctional in some way, and the characters are typically betrayed by the institutions that they accept in their lives.[5] There is also a sentiment echoed by a detective in Narcotics—"Shit rolls downhill"—which describes how superiors, especially in the higher tiers of the Police Department in the series, will attempt to use subordinates as scapegoats for any major scandals. Simon described the show as "cynical about institutions"[45] while taking a humanistic approach toward its characters.[45] A central theme developed throughout the show is the struggle between individual desires and subordination to the group's goals.

Surveillance

[edit]Central to the structure and plot of the show is the use of electronic surveillance and wiretap technologies by the police—hence the title The Wire. Salon described the title as a metaphor for the viewer's experience: the wiretaps provide the police with access to a secret world, just as the show does for the viewer.[27] Simon has discussed the use of camera shots of surveillance equipment, or shots that appear to be taken from the equipment itself, to emphasize the volume of surveillance in modern life and the characters' need to sift through this information.[5]

Cast and characters

[edit]The Wire employs a broad ensemble cast, supplemented by many recurring guest stars who populate the institutions featured on the show. The majority of the cast is black, which accurately reflects the demographics of Baltimore.

The show's creators are also willing to kill off major characters, so that viewers cannot assume that a given character will survive simply because of a starring role or popularity among fans. In response to a question on why a certain character had to die, David Simon said,

We are not selling hope, or audience gratification, or cheap victories with this show. The Wire is making an argument about what institutions—bureaucracies, criminal enterprises, the cultures of addiction, raw capitalism even—do to individuals. It is not designed purely as an entertainment. It is, I'm afraid, a somewhat angry show.[52]

Main cast

[edit]

The major characters of the first season were divided between those on the side of the law and those involved in drug-related crime. The investigating detail was launched by the actions of Detective Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West), whose insubordinate tendencies and personal problems played counterpoint to his ability as a criminal investigator. The detail was led by Lieutenant Cedric Daniels (Lance Reddick) who faced challenges balancing his career aspirations with his desire to produce a good case. Kima Greggs (Sonja Sohn) was a capable lead detective who faced jealousy from colleagues and worry about the dangers of her job from her domestic partner. Her investigative work was greatly helped by her confidential informant, a drug addict known as Bubbles (Andre Royo).

Like Greggs, partners Thomas "Herc" Hauk (Domenick Lombardozzi) and Ellis Carver (Seth Gilliam) were reassigned to the detail from the narcotics unit. The duo's initially violent nature was eventually subdued as they proved useful in grunt work, and sometimes served as comic relief for the viewer.[27] Rounding out the temporary unit were detectives Lester Freamon (Clarke Peters) and Roland "Prez" Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost). Freamon, seen as a quiet "house cat", soon proved to be one of the unit's most methodical and experienced investigators, with a knack for noticing important details and a deep knowledge of public records and paper trails. Prez faced sanction early on and was forced into office duty, but this setback quickly became a boon as he demonstrated natural skill at deciphering the communication codes used by the Barksdale organization.

These investigators were overseen by two commanding officers more concerned with politics and their own careers than the case, Deputy Commissioner Ervin Burrell (Frankie Faison) and Major William Rawls (John Doman). Assistant state's attorney Rhonda Pearlman (Deirdre Lovejoy) acted as the legal liaison between the detail and the courthouse and also had a sexual relationship with McNulty. In the homicide division, Bunk Moreland (Wendell Pierce) was a gifted, dry-witted, hard-drinking detective partnered with McNulty under Sergeant Jay Landsman (Delaney Williams), the sarcastic, sharp-tongued squad supervisor. Peter Gerety had a recurring role as Judge Phelan, the official who started the case moving.[27]

On the other side of the investigation was Avon Barksdale's drug empire. The driven, ruthless Barksdale (Wood Harris) was aided by business-minded Stringer Bell (Idris Elba). Avon's nephew D'Angelo Barksdale (Larry Gilliard Jr.) ran some of his uncle's territory, but also possessed a guilty conscience, while loyal Wee-Bey Brice (Hassan Johnson) was responsible for multiple homicides carried out on Avon's orders. Working under D'Angelo were Poot (Tray Chaney), Bodie (J. D. Williams), and Wallace (Michael B. Jordan), all street-level drug dealers.[27] Wallace was an intelligent but naive youth trapped in the drug trade,[27] and Poot a randy young man happy to follow rather than lead. Omar Little (Michael K. Williams), a renowned Baltimore stick-up man robbing drug dealers for a living, was a frequent thorn in the side of the Barksdale clan.

The second season introduced a new group of characters working in the Port of Baltimore area, including Spiros "Vondas" Vondopoulos (Paul Ben-Victor), Beadie Russell (Amy Ryan), and Frank Sobotka (Chris Bauer). Vondas was the underboss of a global smuggling operation, Russell an inexperienced port authority officer and single mother thrown in at the deep end of a multiple homicide investigation, and Frank Sobotka a union leader who turned to crime to raise funds to save his union. Also joining the show in season 2 were Nick Sobotka (Pablo Schreiber), Frank's nephew; Ziggy Sobotka (James Ransone), Frank's troubled son; and "The Greek" (Bill Raymond), Vondas' mysterious boss. As the second season ended, the focus shifted away from the ports, leaving the new characters behind.

The third season saw several previously recurring characters assuming larger starring roles, including Detective Leander Sydnor (Corey Parker Robinson), Bodie (J.D. Williams), Omar (Michael K. Williams), Proposition Joe (Robert F. Chew), and Major Howard "Bunny" Colvin (Robert Wisdom). Colvin commanded the Western district where the Barksdale organization operated, and nearing retirement, he came up with a radical new method of dealing with the drug problem. Proposition Joe, the East Side's cautious drug kingpin, became more cooperative with the Barksdale Organization. Sydnor, a rising young star in the Police Department in season 1, returned to the cast as part of the major crimes unit. Bodie had been seen gradually rising in the Barksdale organization since the first episode; he was born to their trade and showed a fierce aptitude for it. Omar had a vendetta against the Barksdale organization and gave them all of his lethal attention.

New additions in the third season included Tommy Carcetti (Aidan Gillen), an ambitious city councilman; Mayor Clarence Royce (Glynn Turman), the incumbent whom Carcetti planned to unseat; Marlo Stanfield (Jamie Hector), leader of an upstart gang seeking to challenge Avon's dominance; and Dennis "Cutty" Wise (Chad Coleman), a newly released convict uncertain of his future.

In the fourth season, four young actors joined the cast: Jermaine Crawford as Duquan "Dukie" Weems; Maestro Harrell as Randy Wagstaff; Julito McCullum as Namond Brice; and Tristan Wilds as Michael Lee. The characters are friends from a west Baltimore middle school. Another newcomer was Norman Wilson (Reg E. Cathey), Carcetti's deputy campaign manager.

The fifth season saw several actors join the starring cast. Gbenga Akinnagbe returns as the previously recurring Chris Partlow, chief enforcer of the now dominant Stanfield Organization. Neal Huff reprises his role as mayoral chief of staff Michael Steintorf, having previously appeared as a guest star at the end of the fourth season. Two other actors also joined the starring cast, having previously portrayed their corrupt characters as guest stars—Michael Kostroff as defense attorney Maurice Levy and Isiah Whitlock Jr. as State Senator Clay Davis. Crew member Clark Johnson appeared in front of the camera for the first time in the series to play Augustus Haynes, the principled editor of the city desk of The Baltimore Sun. He is joined in the newsroom by two other new stars; Michelle Paress and Tom McCarthy play young reporters Alma Gutierrez and Scott Templeton.

Episodes

[edit]| Season | Episodes | Originally aired | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aired | Last aired | |||

| 1 | 13 | June 2, 2002 | September 8, 2002 | |

| 2 | 12 | June 1, 2003 | August 24, 2003 | |

| 3 | 12 | September 19, 2004 | December 19, 2004 | |

| 4 | 13 | September 10, 2006 | December 10, 2006 | |

| 5 | 10 | January 6, 2008 | March 9, 2008 | |

Season 1 (2002)

[edit]

The first season introduces two major groups of characters: the Baltimore Police Department and a drug dealing organization run by the Barksdale family. The season follows the police investigation of the latter over its 13 episodes.

The investigation is triggered when, following the acquittal of D'Angelo Barksdale for murder after a key witness changes her story, Detective Jimmy McNulty meets privately with Judge Daniel Phelan. McNulty tells Phelan that the witness has probably been intimidated by members of a drug trafficking empire run by D'Angelo's uncle, Avon Barksdale, having recognized several faces at the trial, most notably Avon's second-in-command, Stringer Bell. He also tells Phelan that no one is investigating Barksdale's criminal activity, which includes a significant portion of the city's drug trade and several unsolved homicides.

Phelan reacts to McNulty's report by complaining to senior Police Department figures, embarrassing them into creating a detail dedicated to investigating Barksdale. However, owing to the department's dysfunction, the investigation is intended as a façade to appease the judge. An intradepartmental struggle between the more motivated officers on the detail and their superiors spans the whole season, with interference by the higher-ups often threatening to ruin the investigation. The detail's commander, Cedric Daniels, acts as mediator between the two opposing groups of police.

Meanwhile, the organized and cautious Barksdale gang is explored through characters at various levels within it. The organization is continually antagonized by a stick-up crew led by Omar Little, and the feud leads to several deaths. Throughout, D'Angelo struggles with his conscience over his life of crime and the people it affects.

The police have little success with street-level arrests or with securing informants beyond Bubbles, a well known West Side drug addict. Eventually the investigation takes the direction of electronic surveillance, with wiretaps and pager clones to infiltrate the security measures taken by the Barksdale organization. This leads the investigation to areas the commanding officers had hoped to avoid, including political contributions.

When an associate of Avon Barksdale is arrested by State Police and offers to cooperate, the commanding officers order the detail to undertake a sting operation to wrap up the case. Detective Kima Greggs is seriously hurt in the operation, triggering an overzealous response from the rest of the department. This causes the detail's targets to suspect that they are under investigation.

Wallace is murdered by his childhood friends Bodie and Poot, on orders from Stringer Bell, after leaving his "secure" placement with relatives and returning to Baltimore. D'Angelo Barksdale is eventually arrested transporting a kilo of uncut heroin, and learning of Wallace's murder, is ready to turn in his uncle and Stringer. However, D'Angelo's mother convinces him to rescind the deal and take the charges for his family. The detail manages to arrest Avon on a minor charge and gets one of his soldiers, Wee-Bey, to confess to most of the murders, some of which he did not commit. Stringer escapes prosecution and is left running the Barksdale empire. For the officers, the consequences of antagonizing their superiors are severe, with Daniels passed over for promotion and McNulty assigned out of homicide and into the marine unit.

Season 2 (2003)

[edit]The second season, along with its ongoing examination of the drug problem and its effect on the urban poor, examines the plight of the blue-collar urban working class as exemplified by dockworkers in the city port, as some of them get caught up in smuggling drugs and other contraband inside the shipping containers that pass through their port.[41] In a season-long subplot, the Barksdale organization continues its drug trafficking despite Avon's imprisonment, with Stringer Bell assuming greater power.

McNulty harbors a grudge against his former commanders for reassigning him to the marine unit. When thirteen unidentified young women are found dead in a container at the docks, McNulty successfully makes a spiteful effort to place the murders within the jurisdiction of his former commander. Meanwhile, police Major Stan Valchek gets into a feud with Polish-American Frank Sobotka, a leader of the International Brotherhood of Stevedores, a fictional dockers' union, over competing donations to their old neighborhood church. Valchek demands a detail to investigate Sobotka. A detail is assigned, but staffed with "humps".

Valcheck threatens Burrell with a disruption of Burrell's confirmation hearings and insists on Daniels. Cedric Daniels is interviewed, having been praised by Prez, Major Valchek's son-in-law, and also because of his work on the Barksdale case. He is eventually selected to lead the detail assigned just to investigate Sobotka; when the investigation is concluded Daniels is assured he will move up to head a special case unit with personnel of his choosing.

Life for the blue-collar men of the port is increasingly hard and work is scarce. As union leader, Sobotka has taken it on himself to reinvigorate the port by lobbying politicians to support much-needed infrastructure improvement initiatives. Lacking the funds needed for this kind of influence, Sobotka has become involved with a smuggling ring. Around him, his son and nephew also turn to crime, as they have few other opportunities to earn money.

It becomes clear to the Sobotka detail that the dead girls are related to their investigation, as they were in a container that was supposed to be smuggled through the port. They again use wiretaps to infiltrate the crime ring and slowly work their way up the chain towards The Greek, the mysterious man in charge. But Valchek, upset that their focus has moved beyond Sobotka, gets the FBI involved. The Greek has a mole inside the FBI and starts severing his ties to Baltimore when he learns about the investigation.

After a dispute over stolen goods turns violent, Sobotka's wayward son Ziggy is charged with the murder of one of the Greek's underlings. Sobotka himself is arrested for smuggling; he agrees to work with the detail to help his son, finally seeing his actions as a mistake. The Greek learns about this through his mole inside the FBI and has Sobotka killed. The investigation ends with the fourteen homicides solved but the perpetrator already dead. Several drug dealers and mid-level smuggling figures tied to the Greek are arrested, but he and his second-in-command escape uncharged and unidentified. The Major is pleased that Sobotka was arrested; the case is seen as a success by the commanding officers, but is viewed as a failure by the detail.

Across town, the Barksdale organization continues its business under Stringer while Avon and D'Angelo Barksdale serve prison time. D'Angelo decides to cut ties to his family after his uncle organizes the deaths of several inmates and blames it on a corrupt guard to shave time from his sentence. Eventually Stringer covertly orders D'Angelo killed, with the murder staged to look like a suicide. Avon is unaware of Stringer's duplicity and mourns the loss of his nephew.

Stringer also struggles, having been cut off by Avon's drug suppliers in New York and left with increasingly poor-quality product. He again goes behind Avon's back, giving up half of Avon's most prized territory to a rival named Proposition Joe in exchange for a share of his supply, which is revealed to be coming from the Greek. Avon, unaware of the arrangement, assumes that Joe and other dealers are moving into his territory simply because the Barksdale organization has too few enforcers. He uses his New York connections to hire a feared assassin named Brother Mouzone.

Stringer deals with this by tricking his old adversary Omar into believing that Mouzone was responsible for the vicious killing of his partner in their feud in season one. Seeking revenge, Omar shoots Mouzone but, realizing Stringer has lied to him, calls 9-1-1. Mouzone recovers and leaves Baltimore, and Stringer (now with Avon's consent) is able to continue his arrangement with Proposition Joe.

Season 3 (2004)

[edit]

In the third season, the focus returns to the street and the Barksdale organization. The scope is expanded to include the city's political scene. A new subplot is introduced to explore the potential positive effects of de facto "legalizing" the illegal drug trade, and incidentally prostitution, within the limited boundaries of a few uninhabited city blocks—referred to as Hamsterdam. The posited benefits, as in Amsterdam and other European cities, are reduced street crime city-wide and increased outreach of health and social services to vulnerable people. These are continuations of stories hinted at earlier.

The demolition of the residential towers that had served as the Barksdale organization's prime territory pushes their dealers back out onto the streets of Baltimore. Stringer Bell continues his reform of the organization by cooperating with other drug lords, sharing with one another territory, product and profits. Stringer's proposal is met with a curt refusal from Marlo Stanfield, leader of a new, growing crew.

Against Stringer's advice, Avon decides to take Marlo's territory by force and the two gangs become embroiled in a bitter turf war with multiple deaths. Omar Little continues to rob the Barksdale organization wherever possible. Working with his new boyfriend Dante and two women, he is once more a serious problem. The violence related to the drug trade makes it an obvious choice of investigation for Cedric Daniels' permanently established Major Crimes Unit.

Councilman Tommy Carcetti begins to prepare himself for a mayoral race. He manipulates a colleague into running against the mayor to split the black vote, secures a capable campaign manager and starts making headlines for himself.

Approaching the end of his career, Major Howard "Bunny" Colvin of Baltimore's Western District wants to effect some real change in the troubled neighborhoods for which he has long been responsible. Without the knowledge of central command, Colvin sets up areas where police would monitor, but not punish, the drug trade. The police crack down severely on violence in these areas and also on drug trafficking elsewhere in the city.

For many weeks, Colvin's experiment works and crime is reduced in his district. Colvin' superiors, the media and city politicians eventually find out about the arrangement and the "Hamsterdam" experiment ends. With top brass outraged, Colvin is forced to cease his actions, accept a demotion and retire from the Police Department on a lower-grade pension. Tommy Carcetti uses the scandal to make a grandstanding speech at a weekly Baltimore city council meeting.

In another strand, Dennis "Cutty" Wise, once a drug dealer's enforcer, is released from a fourteen-year prison term with a street contact from Avon. Cutty initially wishes to go straight partly to reignite his relationship with a former girlfriend. He tries to work as a manual laborer, but struggles to adapt to life as a free man. He then flirts with his former life, going to work for Avon. Finding he no longer has the heart for murder, he quits the Barksdale crew. Later, he uses funding from Avon to purchase new equipment for his nascent boxing gym.

The Major Crimes Unit learns that Stringer has been buying real estate and developing it to fulfill his dream of being a successful legitimate businessman. Believing that the bloody turf war with Marlo is poised to destroy everything the Barksdale crew had worked for, Stringer gives Major Colvin information on Avon's weapons stash. Brother Mouzone returns to Baltimore and tracks down Omar to join forces. Mouzone tells Avon that his shooting must be avenged. Avon, remembering how Stringer disregarded his order which resulted in Stringer's attempt to have Brother Mouzone killed, furious over D'Angelo's murder to which Stringer had confessed, and fearing Mouzone's ability to harm his reputation outside of Baltimore, informs Mouzone of Stringer's upcoming visit to his construction site. Mouzone and Omar corner him and shoot him to death.

Colvin tells McNulty about Avon's hideout and armed with the information gleaned from selling the Barksdale crew pre-wiretapped disposable cell phones, the detail stages a raid, arresting Avon and most of his underlings. Barksdale's criminal empire lies in ruins and Marlo's young crew simply moves into their territory. The drug trade in West Baltimore continues.

Season 4 (2006)

[edit]The fourth season concentrates on the school system and the mayoral race. It takes a closer look at Marlo Stanfield's drug gang, which has grown to control most of western Baltimore's trafficking, and Dukie, Randy, Michael, and Namond – four boys from West Baltimore – as they enter the eighth grade. Prez has begun a new career as a mathematics teacher at the same school. The cold-blooded Marlo has come to dominate the streets of the west side, using murder and intimidation to make up for his weak-quality drugs and lack of business acumen. His enforcers Chris Partlow and Snoop conceal their numerous victims in abandoned and boarded-up row houses where the bodies will not be readily discovered. The disappearances of so many known criminals come to mystify both the major crimes unit investigating Marlo and the homicide unit assigned to solve the presumed murders. Marlo coerces Bodie into working under him.

McNulty is a patrolman and lives with Beadie Russell. He politely refuses offers from Daniels who is now a major and commanding the Western District. Detectives Kima Greggs and Lester Freamon, as part of the major crimes unit, investigate Avon Barksdale's political donations and serve several key figures with subpoenas. Their work is shut down by Commissioner Ervin Burrell at Mayor Clarence Royce's request, and after being placed under stricter supervision within their unit, both Greggs and Freamon request and receive transfer to the homicide division.

Meanwhile, the city's mayoral primary race enters its closing weeks. Royce initially has a seemingly insurmountable lead over challengers Tommy Carcetti and Tony Gray, with a big war chest and major endorsements. Royce's lead begins to fray, as his own political machinations turn against him and Carcetti starts to highlight the city's crime problem. Carcetti is propelled to victory in the primary election.

Howard "Bunny" Colvin joins a research group attempting to study potential future criminals in the middle school population. Dennis "Cutty" Wise continues to work with boys in his boxing gym, and accepts a job at the school rounding up truants. Prez has a few successes with his students, but some of them start to slip away. Disruptive Namond is removed from class and placed in the research group, where he gradually develops affection and respect for Colvin. Randy, in a moment of desperation, reveals knowledge of a murder to the assistant principal, leading to his being interrogated by police. When Bubbles takes Sherrod, a homeless teenager, under his wing, he fails in his attempts to encourage the boy to return to school.

Proposition Joe tries to engineer conflict between Omar Little and Marlo to convince Marlo to join the co-op. Omar robs Marlo who, in turn, frames Omar for a murder and organizes attempts to have him murdered in jail but Omar manages to beat the charge with the help of Bunk. Omar is told that Marlo set him up, so takes revenge on him by robbing the entire shipment of the co-op. Marlo is furious with Joe for allowing the shipment to be stolen. Marlo demands satisfaction, and as a result, Joe sets up a meeting between him and Spiros Vondas, who assuages Marlo's concerns. Having gotten a lead on Joe's connection to the Greeks, Marlo begins investigating them to learn more about their role in bringing narcotics into Baltimore.

Freamon discovers the bodies Chris and Snoop had hidden. Bodie offers McNulty testimony against Marlo and his crew, but is shot dead on his corner by O-Dog, a member of Marlo's crew.[53] Sherrod dies after snorting a poisoned vial of heroin that, unbeknownst to him, Bubbles had prepared for their tormentor. Bubbles turns himself in to the police and tries to hang himself, but he survives and is taken to a detox facility. Michael has now joined the ranks of Marlo's killers and runs one of his corners, with Dukie leaving high school to work there. Randy's house is firebombed by school bullies for his cooperation with the police, leaving his caring foster mother hospitalized and sending him back to a group home. Namond is taken in by Colvin, who recognized the good in him. The major crimes unit from earlier seasons is largely reunited, and they resume their investigation of Marlo Stanfield.

Season 5 (2008)

[edit]The fifth and final season focuses on the media and media consumption.[54] The show features a fictional depiction of the newspaper The Baltimore Sun, and in fact elements of the plot are ripped-from-the-headlines events (such as the Jayson Blair New York Times scandal) and people at the Sun.[55] The season, according to David Simon, deals with "what stories get told and what don't and why it is that things stay the same."[54] Issues such as the quest for profit, the decrease in the number of reporters, and the end of aspiration for news quality would all be addressed, alongside the theme of homelessness. John Carroll of The Baltimore Sun was the model for the "craven, prize hungry" editor of the fictional newspaper.[56]

Fifteen months after the fourth season concludes, Mayor Carcetti's cuts in the police budget to redress the education deficit force the Marlo Stanfield investigation to shut down. Cedric Daniels secures a detail to focus on the prosecution of Senator Davis for corruption. Detective McNulty returns to the Homicide unit and decides to divert resources back to the Police Department by faking evidence to make it appear that a serial killer is murdering homeless men.

The Baltimore Sun also faces budget cuts and the newsroom struggles to adequately cover the city, omitting many important stories. Commissioner Burrell continues to falsify crime statistics and is fired by Carcetti, who positions Daniels to replace him.

Marlo Stanfield lures his enemy Omar Little out of retirement by having Omar's mentor Butchie murdered. Proposition Joe teaches Stanfield how to launder money and evade investigation. Once Joe is no longer useful to him, Stanfield has Joe killed with the help of Joe's nephew Cheese Wagstaff and usurps his position with the Greeks and the New Day Co-Op. Michael Lee continues working as a Stanfield enforcer, providing a home for his friend Dukie and younger brother Bug.

Omar returns to Baltimore seeking revenge, targeting Stanfield's organization, stealing and destroying money and drugs and killing Stanfield enforcers in an attempt to force Stanfield into the open. However, he is eventually shot and killed by Kenard, a young Stanfield dealer.

Baltimore Sun reporter Scott Templeton claims to have been contacted by McNulty's fake serial killer. City Editor Gus Haynes becomes suspicious, but his superiors are enamored of Templeton. McNulty backs up Templeton's claim in order to further legitimize his fabricated serial killer. The story gains momentum and Carcetti spins the resulting attention on homelessness into a key issue in his imminent campaign for Governor and restores funding to the Police Department.

Bubbles is recovering from his drug addiction while living in his sister's basement. He is befriended by Sun reporter Mike Fletcher, who eventually writes a profile of Bubbles.

Bunk is disgusted with McNulty's serial killer scheme and tries to have Lester Freamon reason with McNulty. Instead, Freamon helps McNulty perpetuate the lie and uses resources earmarked for the case to fund an illegal wiretap on Stanfield. Bunk resumes working the vacant house murders, leading to a murder warrant against Partlow for killing Michael's stepfather.

Freamon and Leander Sydnor gather enough evidence to arrest Stanfield and most of his top lieutenants, seizing a large quantity of drugs. Stanfield suspects that Michael is an informant, and orders him killed. Michael realizes he is being set up and kills Snoop instead. A wanted man, he leaves Bug with an aunt and begins a career as a stick-up man. With his support system gone, Dukie lives with drug addicts.

McNulty tells Kima Greggs about his fabrications to prevent her wasting time on the case. Greggs tells Daniels, who, along with Rhonda Pearlman, takes this news to Carcetti, who orders a cover-up because of the issue's importance to his campaign.

Davis is acquitted, but Freamon uses the threat of federal prosecution to blackmail him for information. Davis reveals Maurice Levy has a mole in the courthouse from whom he illegally purchases copies of sealed indictments. Herc tells Levy that the Stanfield case was probably based on an illegal wiretap, something which would jeopardize the entire case. After Levy reveals this to Pearlman, she uses Levy's espionage to blackmail him into agreeing to a plea bargain for his defendants. Levy ensures Stanfield's release on the condition that he permanently retires, while his subordinates will have to accept long sentences. Stanfield sells the connection to The Greeks back to the Co-Op and plans to become a businessman, although he appears unable or unwilling to stay off the corner.

As the cover-up begins, a copy-cat killing occurs, but McNulty quickly identifies and arrests the culprit. Pearlman tells McNulty and Freamon that they can no longer be allowed to do investigative work and warns of criminal charges if the scandal becomes public. They opt to retire. Haynes attempts to expose Templeton, but the managing editors ignore the fabrications and demote anyone critical of their star reporter. Carcetti pressures Daniels to falsify crime statistics to aid his campaign. Daniels refuses and then quietly resigns rather than have his FBI file leaked.

In a final montage, McNulty gazes over the city; Freamon enjoys retirement; Templeton wins a Pulitzer; Carcetti becomes Governor; Haynes is sidelined to the copy desk and replaced by Fletcher; Campbell appoints Valchek as commissioner; Carcetti appoints Rawls as Superintendent of the Maryland State Police; Dukie continues to use heroin; Pearlman becomes a judge and Daniels a defense attorney; Bubbles is allowed upstairs where he enjoys a family dinner; Michael Lee becomes the new stick up boy, replacing Omar; Chris serves his life sentence alongside Wee-Bey; the drug trade continues; and the people of Baltimore go on with their lives.

Prequel shorts

[edit]During the fifth season, HBO produced three shorts depicting moments in the history of characters in The Wire. The three prequels depict the first meeting between McNulty and Bunk; Proposition Joe as a slick business kid; and young Omar.[57] The shorts are available on the complete series DVD set.[58]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Critical response

[edit]| Season | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86% (36 reviews)[59] | 79 (22 reviews)[60] |

| 2 | 95% (21 reviews)[61] | 95 (17 reviews)[62] |

| 3 | 100% (21 reviews)[63] | 98 (11 reviews)[64] |

| 4 | 100% (24 reviews)[65] | 98 (21 reviews)[66] |

| 5 | 93% (44 reviews)[67] | 89 (24 reviews)[68] |

All seasons of The Wire have received positive reviews from major television critics, with seasons two through five in particular receiving near universal acclaim, with several naming it the best contemporary show and one of the best drama series of all time. The first season received mainly positive reviews from critics,[69][59] some even calling it superior to HBO's better-known "flagship" drama series such as The Sopranos and Six Feet Under.[70][71][72] On the review aggregator Metacritic, the first season scored 79 out of 100 based on 22 reviews.[60] One reviewer pointed to the retread of some themes from HBO and David Simon's earlier works, but still found it valuable viewing and particularly resonant because it parallels the war on terror through the chronicling of the war on drugs.[73] Another review postulated that the series might suffer because of its reliance on profanity and slowly drawn-out plot, but was largely positive about the show's characters and intrigue.[33]

Despite the critical acclaim, The Wire received poor Nielsen ratings, which Simon attributed to the complexity of the plot; a poor time slot; heavy use of esoteric slang, particularly among the gangster characters; and a predominantly black cast.[74] Critics felt the show was testing the attention span of its audience and that it was mistimed in the wake of the launch of the successful crime drama The Shield on FX.[73] However, anticipation for a release of the first season on DVD was high at Entertainment Weekly.[75]

After the first two episodes of season two, Jim Shelley in The Guardian called The Wire the best show on TV, praising the second season for its ability to detach from its former foundations in the first season.[34] Jon Garelick with the Boston Phoenix was of the opinion that the subculture of the docks (second season) was not as absorbing as that of the housing projects (first season), but he went on to praise the writers for creating a realistic world and populating it with an array of interesting characters.[76]

The critical response to the third season remained positive. Entertainment Weekly named The Wire the best show of 2004, describing it as "the smartest, deepest and most resonant drama on TV." They credited the complexity of the show for its poor ratings.[77] The Baltimore City Paper was so concerned that the show might be cancelled that it published a list of ten reasons to keep it on the air, including strong characterization, Omar Little, and an unabashedly honest representation of real world problems. It also worried that the loss of the show would have a negative impact on Baltimore's economy.[78]

At the close of the third season, The Wire was still struggling to maintain its ratings and the show faced possible cancellation.[79] Creator David Simon blamed the show's low ratings in part on its competition against Desperate Housewives and worried that expectations for HBO dramas had changed following the success of The Sopranos.[80]

As the fourth season was about to begin, almost two years after the previous season's end, Tim Goodman of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that The Wire "has tackled the drug war in this country as it simultaneously explores race, poverty and 'the death of the American working class,' the failure of political systems to help the people they serve, and the tyranny of lost hope. Few series in the history of television have explored the plight of inner-city African Americans and none—not one—has done it as well."[81] Brian Lowry of Variety wrote at the time, "When television history is written, little else will rival 'The Wire.'"[82] The New York Times called the fourth season of The Wire "its best season yet."[83]

Doug Elfman of the Chicago Sun-Times was more reserved in his praise, calling it the "most ambitious" show on television, but faulting it for its complexity and the slow development of the plotline.[84] The Los Angeles Times took the rare step of devoting an editorial to the show, stating that "even in what is generally acknowledged to be something of a golden era for thoughtful and entertaining dramas—both on cable channels and on network TV—The Wire stands out."[85] Time magazine especially praised the fourth season, stating that "no other TV show has ever loved a city so well, damned it so passionately, or sung it so searingly."[86]

On Metacritic, seasons three and four received a weighted average score of 98.[64][66] Andrew Johnston of Time Out New York named The Wire the best TV series of 2006, and wrote, "The first three seasons of David Simon's epic meditations on urban America established The Wire as one of the best series of the decade, and with season four--centered on the heart-breaking tale of four eighth-graders whose prospects are limited by public-school bureaucracy--it officially became one for the ages."[87]

Several reviewers called it the best show on television, including Time,[86] Entertainment Weekly,[77] the Chicago Tribune,[88] Slate,[54] the San Francisco Chronicle,[89] the Philadelphia Daily News[90] and the British newspaper The Guardian,[34] which ran a week-by-week blog following every episode,[91] also collected in a book, The Wire Re-up.[92] Charlie Brooker, a columnist for The Guardian, has been particularly enthusiastic in his praise of the show, both in his "Screen Burn" column and in his BBC Four television series Screenwipe, calling it possibly the greatest show of the last 20 years.[93][94]

In 2007, Time listed it among the one hundred best television series of all-time.[95] In 2013, the Writers Guild of America ranked The Wire as the ninth best written TV series.[96] In 2013, TV Guide ranked The Wire as the fifth greatest drama[97] and the sixth greatest show of all time.[98] In 2013, Entertainment Weekly listed the show at No. 6 in their list of the "26 Best Cult TV Shows Ever," describing it as "one of the most highly praised series in HBO history" and praising Michael K. Williams's acting as Omar Little.[99] Entertainment Weekly also named it the number one TV show of all-time in a special issue in 2013.[100]

In 2016, Rolling Stone ranked it second on its list of the 100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time and ranked it fourth in 2022.[101] In September 2019, The Guardian, which ranked the show #2 on its list of the 100 best TV shows of the 21st century, described it as "polemical, panoramic, funny, tragic or all of those things at once", saying it was "beautifully written and performed" and was both "TV as high art and TV wrenched from the soul" and "an exemplar of a certain brand of intelligent, ambitious and uncompromising television".[102] In 2021, Empire ranked The Wire at number four on their list of the 100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time.[103] Also in 2021, The Wire was ranked first by the BBC on its list of the 100 greatest TV series of the 21st century.[104] In 2023, Variety ranked The Wire as the seventh-greatest TV show of all time.[105]

Critics have often described the show in literary terms: the New York Times calls it "literary television;" TV Guide calls it "TV as great modern literature;" the San Francisco Chronicle says the series "must be considered alongside the best literature and filmmaking in the modern era;" and the Chicago Tribune says the show delivers "rewards not unlike those won by readers who conquer Joyce, Faulkner or Henry James."[81][83][106][107] 'The Wire Files', an online collection of articles published in darkmatter Journal, critically analyzes The Wire's racialized politics and aesthetics of representation.[108] Entertainment Weekly put it on its end-of-the-decade, "best-of" list, saying, "The deft writing—which used the cop-genre format to give shape to creator David Simon's scathing social critiques—was matched by one of the deepest benches of acting talent in TV history."[109]

Former President of the United States Barack Obama has said that The Wire is his favorite television series.[110] The 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature Laureate, Mario Vargas Llosa, wrote a very positive critical review of the series in the Spanish newspaper El País.[111] The comedian turned mayor of Reykjavík, Iceland, Jón Gnarr, has gone so far as to say that he would not enter a coalition government with anyone who has not watched the series.[112]

Robert Kirkman, creator of The Walking Dead, is a strong follower of The Wire; he has tried to cast as many actors from it into the television series of the same name as possible, so far having cast Chad Coleman, Lawrence Gilliard Jr., Seth Gilliam, and Merritt Wever.[113]

Awards

[edit]

The Wire was nominated for and won a wide variety of awards, including nominations for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing for a Drama Series for "Middle Ground" (2004) and "–30–" (2008), NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Drama Series for each of its five seasons, Television Critics Association Awards (TCA), and Writers Guild of America Awards (WGA).

Most of the awards the series won were for season 4 and season 5. These included the Directors Guild of America Award and TCA Heritage Award for season 5, and the Writers Guild of America Award for Television: Dramatic Series for season 4, plus the Crime Thriller Award, Eddie Award, Edgar Award, and Irish Film & Television Academy Award. The series also won the ASCAP Award, Artios Award, and Peabody Award for season 2.[114]

The series won the Broadcasting & Cable Critics' Poll Award for Best Drama (season 4) and won Time's critics choice for top television show for season 1 and season 3.

Despite the above mentioned awards and unanimous critical approval, The Wire never won a single Primetime Emmy Award, receiving only two writing nominations in 2005 and 2008. Several critics recognized its lack of recognition by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences.[115][116][117] According to a report by Variety, anonymous Emmy voters cited reasons such as the series' dense and multilayered plot, the grim subject matter, and the series' lack of connection with California, as it is set and filmed in Baltimore.[118]

Academia

[edit]In the years following the end of the series' run, several colleges and universities such as Johns Hopkins, Brown University, and Harvard College have offered classes on The Wire in disciplines ranging from law to sociology to film studies. Phillips Academy, a boarding high school in Massachusetts, offers a similar course as well.[119][120] University of Texas at San Antonio offers a course where the series is taught as a work of literary fiction.[121]

In an article published in The Washington Post, Anmol Chaddha and William Julius Wilson explain why Harvard chose The Wire as curriculum material for their course on urban inequality: "Though scholars know that deindustrialization, crime and prison, and the education system are deeply intertwined, they must often give focused attention to just one subject in relative isolation, at the expense of others. With the freedom of artistic expression, The Wire can be more creative. It can weave together the range of forces that shape the lives of the urban poor."[122]

University of York's Head of Sociology, Roger Burrows, said in The Independent that the show "makes a fantastic contribution to their understanding of contemporary urbanism", and is "a contrast to dry, dull, hugely expensive studies that people carry out on the same issues".[123] The series is also studied as part of a Master seminar series at the Paris West University Nanterre La Défense.[124] In February 2012, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek gave a lecture at Birkbeck, University of London titled The Wire or the clash of civilisations in one country.[125] In April 2012, Norwegian academic Erlend Lavik posted online a 36-minute video essay called "Style in The Wire" which analyzes the various visual techniques used by the show's directors over the course of its five seasons.[126]

The Wire has also been the subject of growing numbers of academic articles by, amongst others, Fredric Jameson (who praised the series' ability to weave utopian thinking into its realist representation of society);[127] and Leigh Claire La Berge, who argues that although the less realistic character of season five was received negatively by critics, it gives the series a platform not only for representing reality, but for representing how realism is itself a construct of social forces like the media;[128] both commentators see in The Wire an impulse for progressive political change rare in mass media productions. While most academics have used The Wire as a cultural object or case study, Benjamin Leclair-Paquet has instead argued that the "creative methods behind HBO's The Wire evoke original ways to experiment with speculative work that reveal the merit of the imaginary as a pragmatic research device." This author posits that the methods behind The Wire are particularly relevant for contentious urban and architectural projects.[129]

Broadcast

[edit]HBO aired the five seasons of the show in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2008. New episodes were shown once a week, occasionally skipping one or two weeks in favor of other programming. Starting with the fourth season, subscribers to the HBO On Demand service were able to see each episode of the season six days earlier.[130] American basic cable network BET also aired the show. BET adds commercial breaks, blurs some nudity, and mutes some profanity. Much of the waterfront storyline from the second season is edited out from the BET broadcasts.[131]

The series was remastered in 16:9 high-definition in late 2014. As the series was shot with a 16:9-safe area, the remastered series is an open matte of the original 4:3 framing.[132] Creator David Simon approved the new version, and worked with HBO to remove film equipment and crew members, and solve actor sync problems in the widened frame.[133] The remastered series debuted on HBO Signature, airing the entire series consecutively, and on HBO GO on December 26, 2014.

In the United Kingdom, the show has been broadcast on FX until 2009 when the BBC bought terrestrial television rights to The Wire in 2008, when it was broadcast on BBC Two,[134] although controversially it was broadcast at 11:20 pm[135] and catchup was not available on BBC iPlayer.[136] In a world first, British newspaper The Guardian made the first episode of the first season available to stream on its website for a brief period[137] and all episodes were aired in Ireland on the public service channel TG4 approximately six months after the original air dates on HBO.[138]

The series became available in Canada in a remastered 16:9 HD format on streaming service CraveTV in late 2014.[139]

Home media

[edit]Every season was released on DVD, and were favorably received, though some critics have faulted them for a lack of special features.[9][10][140][141]

The remastered version is on iTunes, and was released as a complete series Blu-ray box set on June 2, 2015.[142][143][144]

DVD releases

[edit]| Season | Release dates | Episodes | Special features | Discs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 4 | ||||

| 1 | October 12, 2004 | April 18, 2005 | May 11, 2005 | 13 |

|

5 |

| 2 | January 25, 2005 | October 10, 2005 | May 3, 2006 | 12 |

|

5 |

| 3 | August 8, 2006 | February 5, 2007 | August 13, 2008 | 12 |

|

5 |

| 4 | December 4, 2007 | March 10, 2008 | August 13, 2008 | 13 |

|

4 |

| 5 | August 12, 2008 | September 22, 2008 | February 2, 2010 | 10 |

|

4 |

| All | December 9, 2008 | December 8, 2008 | February 2, 2010 | 60 |

|

23 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "'The Wire': David Simon reflects on his modern Greek tragedy". Variety. March 8, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (March 6, 2018). "The Wire, 10 years on: 'We tore the cover off a city and showed the American dream was dead'". The Guardian. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c Talbot, Margaret (October 22, 2007). "Stealing Life". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ a b "Real Life Meets Reel Life With David Simon". The Washington Post. September 3, 2002. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f David Simon (2005). "The Target" commentary track (DVD). HBO.

- ^ Sources that refer to The Wire's being praised as one of the greatest television shows of all time include:

- Traister, Rebecca (September 15, 2007). "The best TV show of all time". Salon.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "The Wire: arguably the greatest television programme ever made". Telegraph. London. April 2, 2009. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- Wilde, Jon (July 21, 2007). "The Wire is unmissable television". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- Carey, Kevin (February 13, 2007). "A show of honesty". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- "Charlie Brooker: The Wire". The Guardian. London. July 21, 2007. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- Roush, Matt (February 25, 2013). "Showstoppers: The 60 Greatest Dramas of All Time". TV Guide. pp. 16–17.

- "TV: 10 All-Time Greatest". Entertainment Weekly. June 27, 2013. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Sheffield, Rob (September 21, 2016). "100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- Jones, Emma (April 12, 2018). "How The Wire became the greatest TV show ever made". BBC. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- "The 100 Greatest TV Series of the 21st Century". BBC. October 19, 2021. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c Rothkirch, Ian (2002). "What drugs have not destroyed, the war on them has". Salon.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007.

- ^ Alvarez, Rafael (2004). The Wire: Truth Be Told. New York: Pocket Books. pp. 18–19, 35–39.

- ^ a b c Barsanti, Chris (October 19, 2004). "Totally Wired". Slant Magazine. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Wyman, Bill (February 25, 2005). "The Wire The Complete Second Season". NPR. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Abrams, Jonathan (February 13, 2018). "How Every Character Was Cast on The Wire; excerpt from book, All the Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of The Wire". GQ. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Murphy, Joel (2005). "One on one with ... Lance Reddick". Hobo Trashcan.

- ^ Murphy, Joel (August 23, 2005). "One on One With Michael K. Williams". Hobo Trashcan. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ "Michael K. Williams on Playing Omar on 'The Wire,' Discovering Snoop, and How Janet Jackson Changed His Life". Vulture. January 2, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Deford, Susan (February 14, 2008). "Despite Past With Bill Clinton, Ulman Switches Allegiance". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Zurawik, David (July 12, 2006). "Local figures, riveting drama put The Wire in a class by itself". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Character profile – Jay Landsman". HBO. 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ "Character profile – Dennis Mello". HBO. 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c "The Wire season 1 crew". HBO. 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ "The Wire season 2 crew". HBO. 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ "Character profile – Grand Jury Prosecutor Gary DiPasquale". HBO. 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ^ Simon, David (2006) [1991]. Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets. New York: Owl Books.

- ^ "The Wire + Oz". Cosmodrome Magazine. January 26, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ "Org Chart – The Law". HBO. 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ^ "The Wire season 3 crew". HBO. 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c "The Wire season 4 crew". HBO. 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kois, Dan (2004). "Everything you were afraid to ask about The Wire". Salon.com. Archived from the original on November 19, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "The Wire Complete Third Season on DVD", ASIN B000FTCLSU

- ^ a b Birnbaum, Robert (April 21, 2003). "Interview: George Pelecanos". Identity Theory. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Goldman, Eric. "IGN Exclusive Interview: The Wire's David Simon". Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Alvarez 10.

- ^ ""The Wire" on HBO: Play Or Get Played, Exclusive Q&A With David Simon (page 17)". 2006. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Weiser, Todd (June 17, 2002). "New HBO series The Wire taps into summer programming". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c Shelley, Jim (August 6, 2005). "Call The Cops". The Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Joe Chappelle biography". HBO. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ^ "On The Corner: After Three Seasons Shaping The Wire's Background Music, Blake Leyh Mines Homegrown Sounds For Season Four". Baltimore City Paper. 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ ""The Wire" on HBO: Play Or Get Played, Exclusive Q&A With David Simon (page 16)". 2006. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ "Character profile – Walon". HBO. 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ a b "Nonesuch to Release Music from Five Years of "The Wire"". November 12, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ^ Ryan Twomey, Examining The Wire Authenticity and Curated Realism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, ISBN 978-3-030-45992-5

- ^ a b c d Vine, Richard (2005). "Totally Wired". The Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Fenton, Justin (December 14, 2012). "Donnie Andrews, inspiration for Omar character on "The Wire," dies". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ^ Edwards, Haley Sweetland (June 2, 2013). "Should Martin O'Malley Be President?". Washington Monthly. May/June 2013. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Rashbaum, William K. (January 15, 2005). "Police Say a Queens Drug Ring Watched Too Much Television" (Subscription required). The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Walker, Jesse (2004). "David Simon Says". Reason.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (December 21, 2007). "'The Wire' gets the newsroom right". Variety. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Carol D., Leonnig (December 11, 2006). "'The Wire': Young Adults See Bits of Their Past". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ Alvarez 28, 35–39.

- ^ Alvarez 12.

- ^ "Interviews – Ed Burns". HBO. 2006.

- ^ "Behind The Scenes Part 1 – A New Chapter Begins". HBO. 2006.

- ^ Simon, David (2003). "David Simon Answers Fans' Questions". HBO. Archived from the original on December 4, 2003.

- ^ "Season 4 – Ep. 50 – Final Grades – Synopsis". HBO.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c Weisberg, Jacob (September 13, 2006). "The Wire on Fire: Analyzing the best show on television". Slate. p. 1.

- ^ NPR interview with Simon broadcast the week of January 12, 2008

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan (June 14, 2015). "John Carroll, Former Editor of Los Angeles Times, Dies at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ "HBO Releases Three Prequel Videos for 'The Wire'". BuddyTV. December 5, 2007. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ Bailey, Jason (December 11, 2008). "The Wire: The Complete Series". DVD Talk. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Wire: Season 1". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Wire: Season 1". Metacritic. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 2". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 2". Metacritic. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 3". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Wire: Season 3". Metacritic. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 4". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Wire: Season 4". Metacritic. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 5". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "The Wire: Season 5". Metacritic. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "Television Critics Association Introduces 2003 Award Nominees". Television Critics Association. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Sepinwall, Alan (August 6, 2006). "Taut 'Wire' has real strength". Newark Star-Ledger. p. 1.

- ^ Barnhart, Aaron (2006). "'The Wire' aims higher: TV's finest hour is back". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

- ^ Ryan, Leslie (2003). "Tapping The Wire; HBO Police Drama Tops Television Week's Semiannual Critics Poll List". Television Week.

- ^ a b Robert David Sullivan (2002). "Slow Hand". Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ Simon, David (2004). "Ask The Wire: David Simon". HBO. Archived from the original on May 16, 2007.

- ^ "DVD Request of the Week". Entertainment Weekly. July 11, 2003.

- ^ Garelick, Jon (September 24–30, 2004). ""A man must have a code" – listening in on The Wire". Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Flynn, Gillian (December 23, 2004). "The Best of 2004". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007.

- ^ McCabe, Brent; Smith, Van (2005). "Down To The Wire: Top 10 Reasons Not To Cancel The Wire.". Baltimore City Paper. Archived from the original on April 16, 2005. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Stevens, Dana (December 24, 2004). "Moyers Says "Ciao" to Now, but HBO had better not retire The Wire.". Slate magazine. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Guthrie, Marisa (December 15, 2004). "The Wire fears HBO may snip it". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Goodman, Tim (September 6, 2006). "Yes, HBO's 'Wire' is challenging. It's also a masterpiece". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (September 7, 2006). "Review: "The Wire"". Variety. Retrieved August 21, 2013.