The Fortune Cookie

| The Fortune Cookie | |

|---|---|

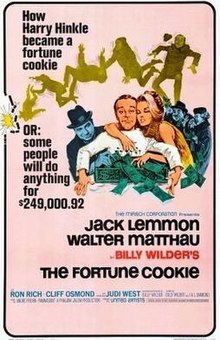

theatrical film poster | |

| Directed by | Billy Wilder |

| Written by | Billy Wilder I.A.L. Diamond |

| Produced by | Billy Wilder |

| Starring | Jack Lemmon Walter Matthau Ron Rich Cliff Osmond Judi West |

| Cinematography | Joseph LaShelle |

| Edited by | Daniel Mandell |

| Music by | André Previn |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3,705,000 |

| Box office | $6,800,000[2] |

The Fortune Cookie (alternative UK title: Meet Whiplash Willie) is a 1966 American black comedy film directed, produced and co-written by Billy Wilder. It is the first film on which Jack Lemmon collaborated with Walter Matthau. Matthau won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance.

Plot

[edit]CBS cameraman Harold "Harry" Hinkle is injured when football player Luther "Boom Boom" Jackson of the Cleveland Browns runs into him during a home game at Municipal Stadium. Harry's injuries are minor, but his conniving lawyer brother-in-law, William H. "Whiplash Willie" Gingrich, convinces him to pretend that his leg and hand have been partially paralyzed so that they can receive a huge indemnity from the insurance company.[3]

Harry reluctantly goes along with the scheme because he is still in love with his ex-wife, Sandy, and being injured might bring her back. The insurance company's lawyers at O'Brien, Thompson and Kincaid suspect that the paralysis is fake, but all but one of their medical experts say that it is real. The experts are convinced by the remnants of a compressed vertebra (in fact, Hinkle suffered the injury as a child), and Hinkle's responses, helped by the numbing injections of novocaine that Gingrich has had a paroled dentist provide. The one holdout, Swiss Professor Winterhalter, is convinced that Hinkle is a fraud.

With no medical evidence to base their case on, O'Brien, Thompson and Kincaid hire Cleveland's best private detective, Chester Purkey, to keep Hinkle under constant surveillance. Gingrich, however, sees Purkey entering the apartment building across the street and lets Hinkle know that they are being watched and recorded. After Sandy arrives, he also warns Hinkle not to indulge in any hanky-panky with her. He proceeds to feed misinformation to Purkey; he incorporates the "Harry Hinkle Foundation", a non-profit charity to which all the proceeds of any settlement are to go, above and beyond the medical expenses.

When Sandy questions Gingrich about this in private, he tells her that it is just a scam to put pressure on the insurance company to settle, and that there will be enough money in the settlement for everyone. Hinkle begins to enjoy having Sandy back again, but he feels bad when he sees that Boom-Boom is so guilt-ridden that his performance on the field suffers. He is booed by the fans, then grounded by the team for getting drunk and involved in a bar fight.

Hinkle wants Gingrich to represent Boom-Boom, but to Hinkle's displeasure, Gingrich says that he is too busy negotiating with O'Brien, Thompson and Kincaid. Hinkle learns that Sandy has returned to him strictly out of greed. Hinkle obtains a $200,000 settlement check. However, Purkey has a plan to expose the scam. He shows up at the apartment supposedly to collect his microphones. He begins to make racist remarks about Boom-Boom. Hinkle, incensed, jumps up from his wheelchair and decks Purkey, but Purkey's assistant Max is not sure if he recorded it on film because "it's a little dark". Hinkle asks Purkey if he would like a second take, turns on a light and advises the cameraman on how to set his exposure. He punches Purkey again, and follows up by swinging from curtain rods and bouncing on the bed. Sandy is crawling on the floor looking for her lost contact lens, and just before Hinkle leaves the apartment, he pushes her down to the ground with his foot.

Gingrich claims that he had no idea that his client was deceiving him, and announces his intention to sue the insurance company lawyers for invasion of privacy, as well as report Purkey's racist remarks to various organizations. Hinkle drives to the stadium, where he finds Boom-Boom leaving the team to become a wrestler named "The Dark Angel". He manages to snap him out of the state, and the two run down the field passing a football back and forth.

Cast

[edit]- Jack Lemmon as Harold "Harry" Hinkle

- Walter Matthau as William H. "Whiplash Willie" Gingrich

- Ron Rich as Luther "Boom Boom" Jackson

- Judi West as Sandy Hinkle

- Cliff Osmond as Chester Purkey

- Lurene Tuttle as Hinkle's mother

- Harry Holcombe as O'Brien

- Les Tremayne as Thompson

- Lauren Gilbert as Kincaid

- Marge Redmond as Charlotte Gingrich

- Noam Pitlik as Max

- Keith Jackson as football announcer[4]

- Harry Davis as Dr. Krugman

- Ann Shoemaker as Sister Veronica

- Ned Glass as Doc Schindler

- Sig Ruman as Professor Winterhalter

- Archie Moore as Mr. Jackson

- Howard McNear as Mr. Cimoli

- William Christopher as Intern (credited as Bill Christopher)

- Dodie Heath as Nun

Production

[edit]

Wilder had Matthau in mind when he wrote the part of "Whiplash Willy". He hoped it would boost his career in movies, but the studio wanted a bigger name.[5] Lemmon originally had two other actors proposed to star with him—Frank Sinatra and Jackie Gleason—but Wilder insisted that he do the picture with Walter Matthau.[citation needed]

Production on the film was halted for weeks after Matthau had a heart attack. By the time he was healthy enough to work and filming started up again, he had slimmed down from 190 to 160 pounds and had to wear a heavy black coat and padded clothing to conceal the weight loss.[6]

Scenes were filmed at Cleveland Municipal Stadium during the Cleveland Browns' 27–17 loss to the Minnesota Vikings at Cleveland Stadium in the afternoon of October 31, 1965. Over 10,000 Clevelanders served as extras.[7] According to The Saturday Evening Post, additional footage was shot the day after the game with Browns players as themselves and the Vikings.[4][citation needed]

Luther "Boom Boom" Jackson's uniform number 44 was actually worn by Leroy Kelly, who was deemed "too small to pass for actor Ron Rich at close range" according to the Post. Ernie Green and a stunt performer stood in for Rich, with the latter for only the sideline-collision scene. In the third consecutive day of shooting, the Kent State University freshman football team replaced the Browns, who were unavailable due to beginning preparations for their next opponent.[4]

Saint Mark's Hospital in the film is the newly completed St. Vincent Charity Hospital, a curved building considered ultramodern at that time. An exterior scene was filmed on East 24th Street, outside an older section of the hospital. Terminal Tower served as the exterior of the law firm. In one scene, one can see Erieview Tower and the steel skeleton of the Anthony J. Celebrezze Federal Building under construction.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "a fine, dark, gag-filled hallucination, peopled by dropouts from the Great Society" and "an explosively funny live-action cartoon about petty chiselers who regard the economic system as a giant pinball machine, ready to pay off to anyone who tilts it properly".[8][9]

Variety found the film "generally amusing (often wildly so), but overlong".[10]

The Hollywood Reporter asserted that The Fortune Cookie was "Billy Wilder's best picture since The Apartment, his funniest since Some Like It Hot".[11]

Box office

[edit]The film grossed $6,000,000 at the North American box office,[12] making it the 31st highest-grossing film of 1966. The film earned $6.8 million worldwide.[2]

Awards and Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Walter Matthau | Won | [13] |

| Best Story and Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Billy Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction – Black-and-White | Robert Luthardt and Edward G. Boyle | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography – Black-and-White | Joseph LaShelle | Nominated | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Walter Matthau | Nominated | [14] |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Won | [15] | |

| Laurel Awards | Top Male Supporting Performance | Won | ||

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Written American Comedy | Billy Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond | Nominated | [16] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b The Fortune Cookie at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b Box Office Information for The Fortune Cookie. IMDb via Internet Archive. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Gingrich initially sues the Cleveland Browns, CBS and Municipal Stadium for $1 million; the settlement is $200,000, equivalent to $1,880,000 in 2023. In the script Gingrich calls this the largest personal injury settlement in Ohio to that time.

- ^ a b c "A 50-year-old ‘Fortune Cookie’ brings some tasty memories of filming at Cleveland stadium," Akron Beacon Journal, Sunday, November 22, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Hazelton, Lachlan (2001). Team Work. The Films of Jack Lemmon & Walter Matthau. Sydney: Sideline Books. p. 15. ISBN 0958007500.

- ^ Stowe, Madelaine (June 25, 2016) Outro to the Turner Classic Movies presentation of the film.

- ^ "Cleveland on Film". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. May 30, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ "'The Fortune Cookie,' Funny Fantasy of Chiselers, Begins Its Run". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (October 20, 1966) "Screen: 'The Fortune Cookie,' Funny Fantasy of Chiselers, Begins Its Run:3 Manhattan Theaters Have Wilder's Film Walter Matthau Stars As Farcical Villain A Western and a Horror Film Also Open Here" The New York Times

- ^ "The Fortune Cookie". Variety. 1 January 1966. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "'The Fortune Cookie': THR's 1966 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 19 October 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "The Fortune Cookie, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "The 39th Academy Awards (1967) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ "The Fortune Cookie". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1966-69". Kansas City Film Critics Circle. 11 December 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

External links

[edit]- The Fortune Cookie at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Fortune Cookie at IMDb

- The Fortune Cookie at the TCM Movie Database

- The Fortune Cookie at AllMovie

- The Fortune Cookie at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1966 films

- 1966 black comedy films

- 1960s satirical films

- American black-and-white films

- American black comedy films

- American football films

- American satirical films

- Cleveland Browns

- 1960s English-language films

- Films scored by André Previn

- Films directed by Billy Wilder

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films set in Cleveland

- Films shot in Cleveland

- Films with screenplays by Billy Wilder

- Films with screenplays by I. A. L. Diamond

- United Artists films

- 1960s American films

- English-language black comedy films