McLean House (Appomattox, Virginia)

McLean House | |

McLean house in April 1865 | |

| Location | Appomattox County, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Appomattox, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°22′37.6″N 78°47′50″W / 37.377111°N 78.79722°W |

| Area | 1,800 acres (728 ha) |

| Built | 1848 |

| Architect | Charles Raine |

| Visitation | 102,397[1] (2019) |

| Part of | Appomattox Court House National Historical Park (ID66000827[2]) |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[2] |

The McLean House near Appomattox, Virginia is within the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park. The house was owned by Wilmer McLean and his wife Virginia near the end of the American Civil War. Hosted by Union General Ulysses S. Grant, the house served as the location of the surrender conference for the Confederate army of General Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, after a nearby battle.[3]

The farmhouse represents the historical style of construction in Piedmont Virginia of the mid-nineteenth century. The current building is a reconstructed form of the original using the original materials. It was carefully deconstructed in the 1890s for shipment and display in Washington, D.C., but those plans fell through, and the materials remained on site. In the 1940s, it ended up in the hands of the National Park Service and was reconstructed on its original foundation, opening to the public in 1949. It was recorded in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966 and in the National Park Service's database of Official Structures in 1989.[4]

History

[edit]

The McLean House was originally constructed by Charles Raine in 1848.[5] Eliza D. Raine's estate sold the house to Wilmer McLean in 1863. It had formerly been a tavern (not to be confused with the nearby Clover Hill Tavern, which Raine had previously owned). One of the first battles of the American Civil War took place on the farm of Wilmer McLean at the Bull Run tributary, the First Battle of Bull Run (First Battle of Manassas). Soon after that battle the McLeans, seeking to avoid the war, moved to the village of Clover Hill, Virginia (the name of which was changed to "Appomattox Court House," having just become the county seat). Because of the name of the village, many mistakenly think the surrender was signed in the courthouse building. (In years past, the county seats of many rural counties, especially in Virginia, had names that were simply the name of the county plus "Court House"; some of these remain today.)[6] The courthouse is about 3 miles (5 km) from the Appomattox Station where the trains came into Appomattox, Virginia.[7]

Because the First Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, took place on Wilmer McLean's farm about 120 miles (190 km) to the north in Virginia, it can be said that the Civil War started in McLean's backyard in 1861 and ended in his parlor in 1865 (although neither event marked the true beginning or ending of hostilities). McLean was a retired major in the Virginia militia. He was too old to enlist at the outbreak of the Civil War and decided to move to get away from the Civil War. After the war, he would say of himself that he moved because he loved peace, but he made a small fortune running sugar through the Union blockade. He was also a slave owner, and there are slave quarters next to McLean's house. Nonetheless, in the morning of Palm Sunday April 9, 1865, the war came back to McLean when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant at his home.[8]

The terms of surrender were: "The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander to sign a like parole for the men of their commands,"... neither "side arms of the officers nor their private horses or baggage" to be surrendered; and, as many privates in the Confederate Army owned horses and mules, all horses and mules claimed by men in the Confederate Army to be left in their possession. The table and chairs used by Lee and Grant when negotiating the surrender are now part of the collections of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, and the Chicago History Museum.[9] After the surrender, many Union soldiers purchased some of McLean's furniture; however, some was stolen.[7] McLean sold pictures of his house after the Civil War; however, he failed financially.[7]

Preservation

[edit]Although he had made a considerable fortune smuggling sugar, McLean's money was in Confederate currency, which became worthless with the collapse of the Confederacy, and he was nearly ruined by the end of the war. In the fall of 1867 the McLeans left Appomattox Court House for Mrs. McLean's estate in Prince William County, Virginia. The banking house of Harrison, Goddin, and Apperson of Richmond, Virginia, obtained a judgment against Wilmer McLean when he defaulted on loans against the property. The house, by then known as the "Surrender House", was sold at public auction on November 29, 1869, and purchased by John L. Pascoe. Records show he then rented it to the Ragland family of Richmond, Virginia.[10]

The renter Nathaniel H. Ragland then purchased the property for $1,250 (~$31,792 in 2023) in 1872. After Nathaniel died in 1888, his widow Martha sold the property in 1891 for $10,000 to a Captain Myron Dunlap of Niagara Falls, New York. Dunlap and some other investors who participated devised a few plans intending to capitalize on the historical significance of the property. One scheme they came up with was to move the disassembled house to Washington, D.C., to become a permanent display as a Civil War museum.[11] There they would charge entrance fees to view the "surrender house" that ended the Civil War. They hired architects to measure drawings including elevations. They also hired contractors for materials specifications lists. The house was disassembled piece by piece and packed for shipping. At this point the investors involved ran out of money and legal problems came about. This scheme was never brought to fruition. The house became just a heaping piles of boards and bricks and sat prey to vandals, collectors, and the environment for fifty years.[10]

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

[edit]Appomattox Court House National Historical Park was created by Congress on April 10, 1940. It included approximately 970 acres (390 ha) at the village once known as Clover Hill. The meticulous reconstruction archeological work began at the site in 1941 amongst overgrown brushes and honeysuckle. One of the first steps was to collect historical data so architectural plans could be drawn up to work from.[10] From the original materials salvable the project included some five thousand original bricks.[7]

The project came to an abrupt stop on December 7, 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces. The United States entered into World War II. Bids for the reconstruction of the McLean House were reopened on November 25, 1947, and work continued. Eighty-four years after the historic surrender, reuniting the country, the McLean House was opened by the National Park Service for the first time to the public on April 9, 1949. In front of a crowd of approximately twenty thousand people a speech was given by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Douglas Southall Freeman.[10] A ribbon was cut by the guests of honor at the dedication ceremony by Major General Ulysses S. Grant III and Robert E. Lee IV on April 16, 1950.[5] The McLean House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[2]

Elizabeth Bacon Custer's will of November 18, 1926, presented to the Probate court of New York City on May 11, 1933, stated: "the two flags of truce, one made of a white towel and the other' of a white handkerchief, which were used on the occasion of the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox, and also a table on which the surrender of General Lee to General Grant was written."[12] The will further explained that these items were at the Memorial Hall of the War Department Building in Washington, D.C.[12]

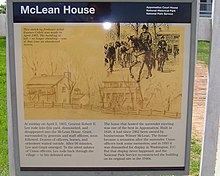

A McLean house marker is at the front gate to the house. The inscription reads:

- At midday on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee rode into this yard, dismounted, and disappeared into the McLean House. Grant, surrounded by generals and staff officers, soon followed. Dozens of officers, horses, and onlookers waited outside. After 90 minutes, Lee and Grant emerged. To the silent salutes of Union officers, Lee rode back through the village – to his defeated army.

- The home that hosted the surrender meeting was one of the best in Appomattox. Built in 1848, it had since 1862 been owned by businessman Wilmer McLean. The house became a sensation after the surrender. Union officers took some mementos; and in 1893 it was dismantled for display in Washington, D.C. But that display never happened, and the National Park Service reconstructed the building on its original site in the 1940s.[13][14]

Historical significance

[edit]The McLean House has meaningful value because of its association with the site of General Robert E. Lee's surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865. It also preserves the distinctive characteristics embodying the style and method of construction typical in Piedmont Virginia in the mid-nineteenth century as well as being typical of a county government seat of that time period. It also represents a typical farming community in Virginia of the mid-nineteenth century.[5]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Visitation By State and by Park for Year: 2019". National Park Service. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "DHR". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Marvel 2000, p. 369.

- ^ "List of Classified Structures-McLean House". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c Jon B. Montgomery; Reed Engle & Clifford Tobias (May 8, 1989). National Register of Historic Places Registration: Appomattox Court House / Appomattox Court House National Historical Park (version from Virginia Department of Historic Resources, including maps) (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (pdf) on January 15, 2009. and Accompanying 12 photos, undated (version from Federal website) (32 KB) and one photo, undated, at Virginia DHR

- ^ Fiske 1902, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d "1961 Park tour guide brochure". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ Kantor 2016, pp. 75–88.

- ^ Kurin 2013, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d "The McLean House – The Post War Years". National Park Service. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ "The McLean House write-up". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ a b "Custer Souvenirs left to Museum". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. May 12, 1933. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Mclean house sign". Flickr - Steve. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Mclean House". Stone Sentinels. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

References

[edit]- Fiske, John (1902). Old Virginia and Her Neighbours. Vol. 2. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. OCLC 03732525.

- Kantor, MacKinlay (2016). Lee and Grant at Appomattox. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-5226-7.

- Kurin, Richard (2013). The Smithsonian's History of America in 101 Objects. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-312815-1.

- Marvel, William (2000). A Place Called Appomattox. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-2568-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Catton, Bruce (1953). A Stillness at Appomattox. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04451-8. LCCN 53-9982.

- Davis, Burke (1992). To Appomattox - Nine April Days, 1865. Eastern Acorn Press. ISBN 0-915992-17-5.

- Kaiser, Harvey H. (2008). The National Park Architecture Sourcebook. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-742-2.

- National Park Service (2002). Appomattox Court House: Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, Virginia. U.S. Dept. of the Interior. ISBN 0-912627-70-0.