Matango

| Matango | |

|---|---|

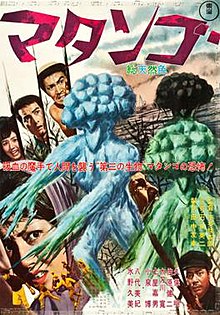

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ishirō Honda |

| Screenplay by | Takeshi Kimura |

| Story by | Shinichi Hoshi Masami Fukushima[1] |

| Based on | "The Voice in the Night" by William Hope Hodgson |

| Produced by | Tomoyuki Tanaka |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Hajime Koizumi |

| Edited by | Reiko Kaneko[2] |

| Music by | Sadao Bekku |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes[2] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Matango (マタンゴ) is a 1963 Japanese horror film directed by Ishirō Honda. The film stars Akira Kubo, Kumi Mizuno and Kenji Sahara. Partially based on William Hope Hodgson's short story "The Voice in the Night", it centers on a group of castaways on an island who are unwittingly altered by a local species of mutagenic mushrooms.

Matango was different from Honda's other films of the period as it explored darker themes and featured a more desolate look. Upon the film's release in Japan, it was nearly banned due to scenes that depicted characters resembling victims of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The film was released directly to television in the United States in a shortened form. Retrospective reviews generally commented on how the film varied from Honda's other work, with its darker tone.

Plot

[edit]Quarantined in a Tokyo mental hospital, a psychology professor named Kenji Murai is visited by a group of doctors asking him about the events that led him there. Murai proceeds to explain how, despite only two of his party being dead, he was the only one to be rescued. He then relates the story of his band of day trippers on a yacht: Murai, wealthy industrialist Masafumi Kasai (the owner of the yacht), salaryman skipper Naoyuki Sakuda, his shipmate assistant Senzō Koyama, celebrity writer Etsurō Yoshida, professional singer Mami Sekiguchi, and student Akiko Sōma. A sudden storm causes the yacht to nearly capsize. Though the boat remains upright, it sustains severe damage during the storm and drifts uncontrollably. The group arrive at a seemingly deserted island and begin to explore. They come across ponds full of fresh rainwater and a forest populated by unusually-large mushrooms.

As they cross the island, they come upon a wrecked ship on the shore whose sails are rotted and its interior is covered with a mysterious mold. Murai, after reading the ship's log, warns them not to eat the mushrooms because they might be poisonous since the former crew had hallucinations after eating them. Finding that the mold is killed by cleaning products, they work to clear it from the ship. In doing so, they begin to suspect that the ship was connected to nuclear tests conducted in the vicinity of the island, with the resultant fallout forcing a bizarre mutation on various organisms native to the surrounding area, including the mushrooms. As the days pass, the group grows restless as their supply of food stores starts to run low. Kasai refuses to help find a way off the island and insists on living in the captain's quarters alone. One night, as Kasai is raiding the food stores, he is attacked by a grotesque-looking man who promptly disappears after encountering the group.

A drunk Yoshida decides to try eating the mushrooms for their hallucinogenic properties. After scuffling with Koyama over Mami, Yoshida pulls a gun and declares his intent to have his way with the women after murdering the others (accepting that if the mushrooms do turn him into a monster, then there will be no consequences for his actions). Subdued by the others, Yoshida is locked in the captain's quarters, ironically ousting Kasai. Kasai tries to convince Naoyuki to abscond together with the food and repaired yacht. Naoyuki violently rebukes this notion, but an unstated amount of time later hogties Kasai and flees with all the gathered food (including Koyama's secret stash that they had been hoarding to extort money from Kasai). Faced with this dire prospect, Mami frees Yoshida and they attempt to take over the ship, shooting and killing Senzō in the process. Murai and Kasai manage to take the gun from Yoshida and force the two off the ship. Some time later, Kasai is confronted by Mami, who entices him to follow her into the forest and eat the mushrooms. Perpetual rainfall has caused wild fungal growth, and Kasai realizes that those who have been eating the mushrooms have turned into humanoid mushroom creatures themselves. The mushrooms are delicious and cannot be resisted after the first bite. Kasai eats the mushrooms, hallucinates scenes of Tokyo nightlife, and falls to his knees amongst the creatures.

Murai finds the yacht adrift and swims out towards it. He finds a note left behind by Naoyuki listing the names of those on the island as dead and how, having now run out of food and energy, he has decided to jump into the sea. Murai draws a large X over the note. Others who have turned into mushroom creatures attack Akiko and Murai. They are separated and Akiko is kidnapped. As Murai tracks her down, he discovers that she has been fed mushrooms and is under their influence along with Mami, Yoshida, and Kasai. Murai attempts to rescue Akiko, but he is overwhelmed by the mushroom creatures and flees without her, making his way onto the yacht and escaping the island. Several days pass later, Murai is finally rescued. As he waits in the hospital, he begins to wonder if he should have stayed with Akiko on the island. His face is revealed to show signs of being infected with fungal growths. Murai states after that it did not matter whether he stayed or not, but he would have been happier there with Akiko. The screen fades as Murai notes that humans are not much different from the mushroom creatures.

Cast

[edit]- Akira Kubo as Professor Kenji Murai

- Kumi Mizuno as Mami Sekiguchi

- Kenji Sahara as Senzō Koyama

- Hiroshi Tachikawa as Etsurō Yoshida

- Yoshio Tsuchiya as Masafumi Kasai

- Hiroshi Koizumi as Naoyuki Sakuda

- Miki Yashiro as Akiko Sōma

- Jiro Kumagai as Doctor at Tokyo Medical Center[3]

- Yutaka Oka as Doctor at Tokyo Medical Center[3]

- Keisuke Yamada as Doctor at Tokyo Medical Center[3]

- Hideyo Amamoto as Matango[4]

- Haruo Nakajima as Matango[3]

- Masaki Shinohara as Matango[3]

- Kōji Uruki as Matango[3]

- Toku Ihara as Matango[3]

- Tokio Ōkawa as Matango[3]

- Kuniyoshi Kashima as Matango[3]

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]The film was based on a story in S-F Magazine which Masami Fukushima was an editor of.[5][1][6][7][8][9] A treatment was written on the film by Shinichi Hoshi and Fukushima which was then made into a screenplay by Takeshi Kimura.[5][6] The story itself was based on William Hope Hodgson's short story "The Voice in the Night", which originally appeared in the November 1907 issue of Blue Book.[5][1][6][7][8][9]

The script was relatively faithful to Hodgson's story, but added a number of extra characters.[5] Honda was also inspired by a news story about a group of rich kids who took their father's yacht far into the sea and had to be rescued. Early drafts featured characters paralleling their real-life counterparts, as well as reports of ships and aircraft vanishing in the Bermuda Triangle.[10]

Filming

[edit]Around this time, there were people who started to be Americanized, or have a very modern lifestyle. There were rich people who sent their kids to school in foreign cars, that kind of thing. We tried to show that type of social background in this film.

— Honda on the film's social themes.[10]

Director Ishirō Honda was better known for his kaiju (giant monster) films, but occasionally developed horror films such as The H-Man (1958) and The Human Vapor (1960), where characters become bizarre transformed beings.[11] Honda's last film in this style was Matango.[11] Critic Bill Cooke noted in Video Watchdog that Matango defies easy categorization as a film belonging to either the kaiju (monster) or kaidan (ghost) genres of the era.[5] In his book Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films, Stuart Galbraith IV described it as a psychological horror film that "contains science fiction elements".[12]

In their book Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa, Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski stated that both thematically and visually, Matango was "uniquely dark" among Honda's films and was a radical departure from his brightly lit and lighthearted films Mothra and King Kong vs. Godzilla.[13] Art director Shiegkazu Ikuno designed the stark look of the film.[13] Ikuno was the apprentice of the production designer of Godzilla, Satoru Cuko. Assistant director Koji Kajita described Ikuno as being known for set designs that were "vanguard, experimental sets".[13] Tomoyuki Tanaka produced the film, with music by Sadao Bekku and cinematography by Hajime Koizumi.[1]

According to Yoshio Tsuchiya, Honda took the project seriously, telling actors before production that the film was "a serious drama picture, so please keep this in mind and work accordingly".[13] Tsuchiya also explained that in addition to the official ending of the film, a different ending was shot where Kubo's face was normal.[14]

Special effects

[edit]Matango was Honda's first film to use the Oxberry optical printer, which Toho purchased from the United States to allow for better image compositing.[13] The printer allowed the ability to superimpose up to five composite shots, allowing the crew to avoid costly hand-painted mattes and glass shots.[15]

Release

[edit]

Toho released the film in Japan on August 11, 1963.[1] Honda described it later as a film that was not "a typical Japanese mainstream movie at all", saying, "When critics saw it, [they] didn't like it, so that was pretty much the end of that film".[14] Matango was nearly banned in Japan because some of the makeup resembled the facial disfigurements characteristic of the victims of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[11]

Matango was Honda's first science fiction film not to receive a theatrical release in the United States. There, American International Television released it directly to television in 1965 as Attack of the Mushroom People.[1][14] This version of the film had a run-time of 88 minutes. Toho produced an English-dubbed version of the film, but it is uncertain when it was officially released.[1]

Prior to Matango's release on home video, Galbraith noted that the film was shown frequently on American television during the 1960s and 1970s, but as of 1994, it "ha[d] all but disappeared".[12] Ryfle and Godziszewski stated that Matango was considered an obscure film for many years after its release.[14]

The film was released on home video in the United Kingdom in the 1980s under the title Fungus of Terror.[11] Media Blasters issued Matango on DVD in the United States on March 15, 2005. It featured a generous selection of extras, including commentary by the film's male lead, Kubo, production sketches, an interview with special effects team member Teruyoshi Nakano, and other features.[16] Tim Lucas of Sight & Sound described Tokyo Shock's release of the film as "a revelation to those of us who grew up watching pan-and-scanned, re-edited bastardisations of these films on television".[11] Lucas also noted that "Matango looks splendid on Tokyo Shock's disc, its anamorphic transfer retaining the naturalistic colour of the earlier Toho Video laserdisc release with brighter contrast and a slightly more generous (2.53:1) screen width". He felt that "the English subtitles access adult dimensions of the story that were never apparent in the old television prints".[11] Toho released the film on Blu-ray in Japan on November 3, 2017.[17]

Reception

[edit]In a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin assessed an 89-minute English dub of the film.[18] The review noted that the film was "not one of the best of Toho's special effect exercises though the mushroom people are quite fanciful and the mushrooms come in all shapes, sizes and colours", and that most scenes were "disappointingly dull" as "the whole thing sags miserably in the middle when characters get down to bickering among themselves".[18]

Matango has been described as a "virtually unknown film", except to "aficionados of Asian cult cinema, fans of weird literature, and sleepless consumers of late-night television programming".[19] The film has received relatively little scholarly attention.[19] Galbraith described Matango as one of Toho's "most atypical and interesting films".[12] He noted that the film was not as strong as its source story, and that the creatures in their final form were "rubbery and unconvincing", but that the film was "one of the most atmospheric horror films to ever come out of Japan".[7] In his book Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo!, Galbraith later compared the English version with the Japanese original, giving the versions 2.5 and 3.5 stars, respectively.[20] In another retrospective review, Lucas stated that the film was the best of Honda's non-kaiju themed horror films, and that it was a "well-crafted picture that parallels 1956's Invasion of the Body Snatchers".[11] Cooke described the film as "a classic from Japan's early-Sixties horror boom" and as "some of the finest work of Ishiro Honda".[6] He also opined that the film was one of Toho's "most colorful science-fiction productions" with a "rich and varied palette".[21] In Leonard Maltin's film guide, the film received 2.5 out of 4 stars, with Maltin writing, "Initially slow-paced [it] grows into a disturbing, peculiarly intimate kind of horror, unusual for director Honda".[22]

Aftermath and influence

[edit]Honda reflected on Matango decades afters its initial release, stating that it was a comment on the "'Rebel era" in which people were becoming addicted to drugs. Once you get addicted, it's a hopeless situation". He added that "no matter how good friends people are, even if they're the very best of friends, under certain conditions things can get very ugly".[23][24] Actor Kubo declared that of the few monster or outer space-themed films which he acted in, Matango was his favorite.[21] Filmmaker Takashi Yamazaki said that Matango may have been the first film he ever saw during his childhood.[25] Director Steven Soderbergh stated he had wanted to make a remake of Matango, describing it as a film that he watched as a child that "scared the shit out of me".[26] Soderbergh said he was unable to reach a deal with Toho, so the remake did not happen.[26] Filmmaker John Carpenter and actor Nicolas Cage are also fans of the film.[27] According to Carpenter, Toho once asked him to create a remake of Matango but he rejected the offer.[28]

In his book analyzing the kaiju film, Jason Barr noted that Matango was the most famous of films of the genre between the 1960s and 1970s that focused on themes of metamorphosis and assault on human bodies.[29] In the book Monsters and Monstrosity from the Fin de Siecle to the Millennium: New Essays, Camara stated that Matango would leave an imprint on Japanese cyberpunk influenced body horror films of the future such as Sogo Ishii's Electric Dragon 80.000 V, Shozin Fukui's Pinocchio 964 and Yoshihiro Nishimura's Tokyo Gore Police.[30]

See also

[edit]- List of horror films of 1963

- List of Japanese films of 1963

- The Last of Us – a 2013 video game featuring creatures infected by a mutated fungus

- Cordyceps – a genus of fungi often parasitic on insects and other arthropods

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Galbraith IV 2008, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d "マタンゴ". Toho (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 71.

- ^ Tanaka 1983, p. 527.

- ^ a b c d e Cooke, Bill (2006). "Matango". Video Watchdog. No. 124. p. 55. ISSN 1070-9991.

- ^ a b c d Cooke, Bill (2006). "Matango". Video Watchdog. No. 124. p. 54. ISSN 1070-9991.

- ^ a b c Galbraith IV 1994, p. 86.

- ^ a b Camara 2015, p. 70.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 198.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lucas, Tim (February 2006). "You Are What You Eat". Sight & Sound. Vol. 16, no. 2. British Film Institute. pp. 87–88. ISSN 0037-4806.

- ^ a b c Galbraith IV 1994, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 199.

- ^ a b c d Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 200.

- ^ Camara 2015, p. 88.

- ^ "Matango (1963) - Ishiro Honda". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "マタンゴ Blu-ray" (in Japanese). Toho. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Matango (Matango - Fungus of Terror)". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 36, no. 420. London: British Film Institute. 1969. p. 216.

- ^ a b Camara 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Galbraith IV 1998, p. 139.

- ^ a b Cooke, Bill (2006). "Matango". Video Watchdog. No. 124. p. 56. ISSN 1070-9991.

- ^ Maltin 2015, p. 439.

- ^ Camara 2015, p. 79.

- ^ Camara 2015, p. 80.

- ^ "『ゴジラ-1.0』山崎貴監督 作りながら感じたゴジラ映画と神事". Nikkei xTREND (in Japanese). November 24, 2023. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Steven Soderbergh: 'There's no new oxygen in this system'". Little White Lies. August 23, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Ongley, Hannah (November 28, 2022). "Nicolas Cage and John Carpenter are cinema's most studious eccentrics". Document Journal. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "I Don't Worry About My Oeuvre: A Conversation with John Carpenter". Los Angeles Review of Books. November 2, 2022. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ Barr 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Barr 2017, p. 10.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Barr, Jason (2016). The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema's Biggest Monsters. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476623955.

- Barr, Jason (2017). Mustachio, Camille D.G.; Barr, Jason (eds.). Giant Creatures in Our World: Essays on Kaiju and American Popular Culture. ISBN 978-1476629971.

- Camara, Anthony (2015). Hutchinson, Sharla; Brown, Rebecca A. (eds.). Monsters and Monstrosity from the Fin de Siecle to the Millennium: New Essays. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476622712.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1994). Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-853-7.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1998). Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo!: The Incredible World of Japanese Fantasy Films. Feral House. ISBN 0922915474.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461673743.

- Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0819577412.

- Maltin, Leonard (2015). Classic Movie Guide: From the Silent Era Through 1965. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-14-751682-4.

- Medved, Michael; Medved, Harry (1980). The Golden Turkey Awards. Perigee Trade. ISBN 978-0399504631.

- Motoyama, Sho; Matsunomoto, Kazuhiro; Asai, Kazuyasu; Suzuki, Nobutaka; Kato, Masashi (September 28, 2012). Toho Special Effects Movie Complete Works (in Japanese). villagebooks. ISBN 978-4864910132.

- Tanaka, Tomoyuki (1983). The Complete History of Toho Special Effects Movies (in Japanese). Toho Publishing Business Office. ISBN 4-924609-00-5.

External links

[edit]- Matango at IMDb

- Matango at the TCM Movie Database

- Matango at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1963 films

- 1963 horror films

- 1960s science fiction horror films

- Japanese natural horror films

- 1960s Japanese-language films

- Japanese science fiction horror films

- 1960s monster movies

- Films based on British short stories

- Films set on islands

- Toho tokusatsu films

- Films directed by Ishirō Honda

- Films produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka

- Fictional fungi

- Films based on adaptations

- Films set on ships

- 1960s Japanese films

- Films about vacationing

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Films scored by Sadao Bekku

- Kaiju films