Mastaba of Hesy-Re

The Mastaba of Hesy-re is an ancient Egyptian tomb complex in the great necropolis of Saqqara in Egypt. It is the final resting place of the high official Hesy-re, who served in office during the Third Dynasty under King Djoser (Netjerikhet). His large mastaba is renowned for its well-preserved wall paintings and relief panels made from imported Lebanese cedar, which are today considered masterpieces of Old Kingdom wood carving. The mastaba itself is the earliest example of a painted tomb from the Old Kingdom and the only known example from the Third Dynasty. The tomb was excavated by the Egyptologists Auguste Mariette and James Edward Quibell.

Discovery and excavation

[edit]

The mastaba of Hesy-re was originally excavated in 1861 by Auguste Mariette and Jacques de Morgan. Mariette quickly discovered the famous niched gallery with its wooden panels and had these valuable artefacts brought to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. He found the grave shafts empty. In his journal, Mariette records his amazement at the wall paintings and wooden panels. However he erroneously described the mudbrick from which the tomb is built as "yellowish" when it is black. In the opinion of the later excavator James Edward Quibell, he had not worked very carefully and after the removal of the objects, the Hesy-re mastaba was covered over and again and abandoned. He completely neglected to have the mastaba included in the plans of de Morgan or to note its location himself.

The excavations of James Edward Quibell began in 1910 and ended in 1911. A second season ran from 1911 until 1912. Quibell initially had trouble finding Hesy-re's tomb on account of the poor account left by Mariette. However, a former excavation assistant remembered the tomb's location and led Quibell there. The first thing which Quibell's team located was the niched gallery decorated with wall paintings. The passage was filled in and roofed over with reeds, wood planks and some rubble on the same day, since the paint had begun to peel immediately on exposure to the sun. Additionally, Quibell claimed that the corridor was so narrow that visitors and excavators were at risk of rubbing the paint off the walls with their shoulders as they walked through it. Thus it was decided to fill the passage in again after a complete survey, illustrations and photographs had been carried out. Quibell reported also that he had to employ security personnel in exceptional quantity, to keep watch over the tomb day and night, in order to prevent theft and damage by graverobbers and vandals seeking either treasure or controversy.

Significance of the tomb

[edit]The mastaba of Hesy-re is of exceptional significance for both archaeology and Egyptology, since it demonstrates clear developments in the structure and decoration of tombs when compared to earlier mastabas. In addition, innovations and precursors of ideas and practices pertaining to ancient Egyptian funerary cult and beliefs about the afterlife are found here.

Earlier mastabas, especially from the late Second Dynasty, contained offering steles and the depiction of the deceased was limited to these. In the tomb of Hesy-re, the so-called false doors in which the deceased are portrayed standing or walking appear for the first time. Furthermore, the tomb of Hesy-re is the first of its kind in which a full offering list appears, which would become an essential part of the tombs in later generations (as for example in the mastabas of Khabawsokar, Rahotep, and Metjen). There, the depictions of grave goods were completed by images of people bringing offerings. With the new form of tomb decoration begun by Hesy-re, the tomb owner gained more possibilities for symbolic representation: he could now leave and re-enter the tomb through the false door and more offerings were now available to him.[2] In addition, the figural images on the cedar wood panels mark a first key point in the artistic development of tomb decoration: the deceased was no longer indicated by an anthropomorphic silhouette, he is now depicted more naturalistically. A somewhat similar style has since been uncovered in the underground galleries under the contemporary Pyramid of Djoser, in which the Pharaoh is depicted running in the Sed festival.[3]

Description

[edit]Location

[edit]Hesy-re's mastabe (S2405) is located in the northern part of Saqqara, about 260 metres northeast of the pyramid complex of King Djoser in tomb sector G2-G3. The tomb is squeezed in between about a dozen other official graves, which date from between the Protodynastic period and the Fourth Dynasty, which are themselves packed close together.

Size and materials

[edit]The mastaba of Hesy-re was originally about 43 metres long and at least 5 metres high; it is oriented only ca. +11° off a north-south axis. Black, baked mudbrick was used as the building material. Interior rooms, including corridors and the exterior walls of the mastaba were originally carefully covered in white limestone plaster. The exterior walls were also decorated with an imitation of a palace facade. The entire monument is a massive mudbrick building, completed with grey granite door frames and decorative cedar wood panels.

Exterior and interior architecture

[edit]

The 'official' entrance is located on the east side. A wall stands in front of the east wall of the mastaba, forming a narrow corridor. This corridor leads south and then turns to the west after 16 metres in order to run along the south side of the mastaba. There it widens into a kind of anteroom, which was blocked up immediately after completion. The north side of the anteroom was decorated with a frieze at the time of excavation depicting people, livestock and a crocodile. This is now in the Cairo museum. Slight remains indicate that the south side of the anteroom may also have been decorated. The anteroom led on to the serdab, which extended in a southerly direction and contained the stone base of a ka-statue which was not preserved. The corridor led on from the serdab in a westerly direction. Another corridor branches off to the north after 6 metres, where it terminates in a 23 metre long passage. This was originally sealed with six blocks of granite, but grave robbers destroyed these in antiquity. After this first branch, the entrance corridor continued another 4 metres to the west, where it turned off to the north and ended in a 37 metre long niched gallery. The niches were painted and contained eleven decorated wooden panels.

In the centre of the mastaba is an isolated, elongated niched room, which was walled with mudbricks; Quibell suggested that the room was either installed for religious/magical practice or because of an alteration to the plan of the building in the course of construction.

Near the west end of the mastaba, an isolated vertical shaft sinks 21 metres down to the underground grave chambers. These are oriented to the south and divided into three levels. The top level contains two main passages which lead to several rooms and magazines. The west passage divides into two and ends in stairs which descend to the other two levels and lead to unfinished passages. The actual grave chamber had already been plundered when it was discovered.

Wood panels

[edit]

The most significant objects from the grave of Hesy-re are the decorated Lebanese cedar panels. From the very fact that cedar wood was imported and worked in such quantity, it seems that Hesy-re was not just a high-ranking and influential man, but also very rich. Typical Egyptian woods like palm and sycomore were only suitable for very limited work, since they are very soft. For steles, ship planks, and architectural elements, it was necessary to use to use better wood, like the Lebanon cedarwood.

The panels of Hesy-re were originally 1.14 metres high and 0.57 metres wide. Of the eleven panels which were found, six were nearly whole, while only fragments could be recovered from the other five. They were found in the niches of a palace facade and each was fastened by a square peg to a small rectangular opening in the wall of the niche. Today the panels are on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

All the wooden panels are decorated with reliefs of high artistic quality. They preserve figural depictions of Hesy-re, who is shown standing in an official role or sitting at an offering table. While his face is shown in profile, his body is shown in a 3/4 view, so that all parts of his body can be seen. This style of perspective is entirely typical of the relief art of the Old Kingdom, as is the fact that Hesy-re's angular face with a false beard is modelled on that of his king Djoser. With each portrait, Hesy-re appears older: in the first panel, Hesy-re is depicted as a young, upstanding man and already has the high rank of "royal scribe" and "royal confidant." On the last relief, Hesy-re is depicted as a very old man sitting at an offering table. Here he is probably shown at the high point of his career, bearing titles such as Elder of Qed-Hetep and Chief of Pe.

The inscriptions accompanying the portraits name the high offices and titles which Hesy-re held. In addition, the normal numerous offering are listed, such as bread (Egypt. ta), beer (henket), incense (senetjer) and meat (kaw).

These panels are almost without parallel in Egyptian art. The closest example is the stele of the high official Merka from Saqqara, which dates to the end of the First Dynasty. In his grave, a single stele depicting Merka sitting down and including his titles, was found in a niche in the facade of the tomb. The main differences from Hesy-re's panels are the number of them (Merka had only one) and the fact that Merka's stele was carved in stone.[5]

Individual panels

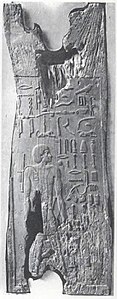

[edit]CG 1426

[edit]Relief "Cairo Museum CG 1426" is well-preserved. It shows Hesy-re sitting at an offering table. All other panels show him standing opposite it (at least in the well preserved ones). In this panel, he wears a long tight garment, which covers his left shoulder but leaves the right one free. On the left shoulder is some kind of knot. The garment reaches down to his ankles. In his left hand, Hesy-re holds two rods. Scribal utensils hang from his right shoulder. These consist of an inkpot with two holes for red and black paint, a reed writing stick and a bag. Hesy-re's right arm is extended toward the offering table. The offering table reaches up to his left. On the actual offering plate are eight loaves of bread. Directly above the table is a short offering list, including wine, incense, cool water, beef(?) meat and antelope meat. In the upper part of the relief is a full list of Hesy-re's titles: Chief dentist,[6] Heka Priest of Mehyt, Elder of Qed-hetep,[7] He who sees Min,[8] Acquaintance of the King, Overseer of the Craftsmen of the King, Great one of the Headscarf (?),[9] Father of Min, Overseer of the Cult Building of Mehyt, Great one of Buto,[10] Foremost of the Couriers (?),[11] Great One of the Ten of Upper Egypt, Priest of Horus of the Harpoon-place of Buto (?).[12]

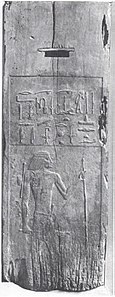

CG 1427

[edit]The relief "Cairo Museum CG 1427" is very fully preserved. Hesy-re is depicted standing. He wears a large wig. In his left hand he holds scribal utensils: an inkpot with two openings for red and black ink, and a rod in which his writing brushes would be stored. He also holds a long rod in this hand. In the other hand, which hangs at his side, he holds a Kherep sceptre, a symbol of power. In the space above Hesy-re is a selection of his titles: Elder of Qed-hetep, Father of Min, Overseer of the Cult Building of Mehyt, King's Acquaintance, Overseer of the Craftsmen of the King, and Great One of the Ten of Upper Egypt. Above the titles is an empty space, which was probably originally incorporated into the niche of the mastaba and thus not visible. A slot is also visible, which was used to fasten the panel to the wall.

CG 1428

[edit]The relief "Cairo Museum CG 1428" is almost completely preserved, although it has some damage in the lower and upper parts. Hesy-re is depicted standing. He wears a short wig with ringlets. Scribal utensils hang over his right shoulder, which consist of an inkpot with two openings for red and black paint, a bag and a long rod, which would hold writing brushes. Both arms hang at his sides and Hesy-re seems not to hold anything in his hands, although the right hand is largely destroyed. In front of Hesy-re is a short offering list, which includes beef, poultry, drinks (e.g. wine) and incense. In the upper part of the panel are Hesy-re's titles: Great One of the Ten of Upper Egypt, Heka Priest of Mehyt, Father of Min, He who sees Min, Overseer of the Royal Scribes,[13] and Overseer of the Craftsmen of the King.

CG 1429

[edit]The relief "Cairo Museum CG 1429" is largely preserved. Hesy-re is shown standing. In his left hand he holds a long rod, in his right a khereb sceptre. Hesy-re wears a shoulder-length wig and a short loincloth. The lower part of the image is largely lost. Above the image is a portion of his titulature, which is identical to panel CG 1427.

CG 1430

[edit]The relief "Cairo Museum CG 1430" is now about 86 cm high and 41 cm wide. The lower part is lost. Hesy-re is depicted standing. He wears a short wig with locks. In his left hand, he holds a rod to his chest. Scribal utensils hang over his right shoulder, of which the inkpot with red and black ink holes are most visible. In front of Hesy-re is a short offering list. Above is the titulature of Hesy-re, which is identical to panel CG 1427.

- The individual panels

-

Cairo Museum CG 1426

-

Cairo Museum CG 1427

-

Cairo Museum CG 1428

-

Cairo Museum CG 1429

-

Cairo Museum CG 1430

Wall paintings

[edit]The niches in which the panels were found were plastered and painted with geometric designs. At the time of the excavation the colours were still clearly recognisable: red, green, black, yellow and white. The aforementioned palace facade does not really form the outer wall of the west wall, since a free-standing wall stands opposite it. The inner side of this wall was originally completely decorated with paint. The paintings of the west wall can be separated into three registers: the lowest consisted of a smooth red band with black spaces above and below.

Above this was a series of reed motifs with various green and yellow patterns. Above this was another red band. On the east wall, the lowest register consisted of a green and yellow diamond pattern. Above this was a painted depiction of the grave offerings of Hesy-re, which include offerings like bread, poultry, dates and wine; in addition there were images of oil and ornamental vessels as well as equipment for hunting and writing. Various types of beds and couches and a table with feet, whose upper side is decorated with a soiled snake, decorated the west wall. Each of these objects was accompanied by a short inscription, which were also painted, and describe the objects and the contents of the vessels.

Above the depictions of the grave offerings is a pattern of ten lined designs in red, white and black. To protect these valuable wall paintings, the mastaba has been closed to any further excavation. Unfortunately, large parts of the decoration had already been destroyed by the elements and fire damage from grave robbers' torches.

Objects discovered

[edit]Numerous smashed ornamental and storage vessels were discovered. The majority were made of alabaster, breccia or clay and seem to have had inscriptions in black paint. Broken jug seals were also found. Among these were two cylinder sealings with the Horus name of King Djoser "Hor-Netjerikhet", which allows the tomb to be dated to this reign. The few remaining intact clay pots contained the valuable "Seti-shemai" oil, among other things. Among the bones found in the tomb were two skulls and other body parts, which J. E. Quibell believed to derive from two different people. Since the skeletal remains have been lost in the meanwhile, certainty is not possible.

References

[edit]- ^ J. E. Quibell: Excavations at Saqqara 1911–1912. The Tomb of Hesy. Cairo 1913, Bildtafel 28; Obj. No. 28.

- ^ Emad El-Metwally. Entwicklung der Grabdekoration in den altägyptischen Privatgräbern. pp. 21 - 23 & 81

- ^ W. S. Smith, W. K. Simpson: The art and architecture of ancient Egypt. Haven 1998, p. 33.

- ^ J. E. Quibell: Excavations at Saqqara 1911–1912. The Tomb of Hesy. Cairo 1913, table 29; Obj. No. 2.

- ^ Stan Hendricks. "Les grands mastabas de la Ire dynastie a Saqqara." Archeo-Nil 19 (2008), fig. 5 on p. 65

- ^ Dilwyn Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I. (= BAR international series. Vol. 866). Archaeopress, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-84171-069-5, p. 318, No. 1412 (The translation and reading of the title is not certain, but is accepted by a large portion of academics. Other possibilities are Chief of Ivory or Arrow carver).

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, II. Oxford 2000, p. 905, No. 3320.

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I. Oxford 2000, p. 423, No. 1566.

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I. Oxford 2000, p. 384, No. 1421 (the translation of the title is not certain).

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I.Oxford 2000, p. 385, No. 1424

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I. Oxford 2000, p. 495, No. 1853 (The translation of the title is very uncertain).

- ^ D. Jones. An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, II. Oxford 2000, p. 556, No. 2059 (The translation of the title is very unclear).

- ^ D. Jones: An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom, I. Oxford 2000, pp. 467-68, No. 1739.

- ^ J. E. Quibell: Excavations at Saqqara 1911–1912. The Tomb of Hesy. Cairo 1913, table 28; Obj. No. 23.

Bibliography

[edit]- James Edward Quibell. Excavations at Saqqara 1911–1912. The Tomb of Hesy. Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Kairo 1913 (Online version).

- Henriette Antonia Groenewegen-Frankfort. Arrest and movement. An essay on space and time in the representational art of the ancient Near East. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1987, ISBN 0-674-04656-0, pp. 29–31.

- Emad El-Metwally. Entwicklung der Grabdekoration in den altägyptischen Privatgräbern. Ikonographische Analyse der Totenkultdarstellungen von der Vorgeschichte bis zum Ende der 4. Dynastie (= Göttinger Orientforschungen, Reihe 4: Ägypten, Band 24). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-447-03270-7 (Dissertation, Universität Göttingen 1991).

- Jochem Kahl, Nicole Kloth, Ulrike Zimmermann. Die Inschriften der 3. Dynastie. Eine Bestandsaufnahme (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, Vol. 56). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-447-03733-4.

- William Stevenson Smith, William Kelly Simpson. The art and architecture of ancient Egypt. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Yale University Press, New Haven (Connecticut) 1998, ISBN 0-300-07747-5.

- Michael Rice. Who's who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London u. a. 1999, ISBN 0-415-15448-0, p. 67.

- Whitney Davis. "Archaism and Modernism in the Reliefs of Hesy-Ra." In John Tait (Ed.): Never had the like occurred. Egypt's View of Its Past (= Encounters with ancient Egypt). UCL Press, London 2003, ISBN 1-84472-007-1, pp. 31–60 (Extracts on Google Books).

- Hermann A. Schlögl. Das Alte Ägypten. Geschichte und Kultur von der Frühzeit bis zu Kleopatra. Beck, München 2006, ISBN 3-406-54988-8; p. 85, 380.