Massasoit (statue)

| Massasoit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Cyrus Dallin |

| Completion date | 1921 |

| Location | Plymouth, Massachusetts, U.S. |

Massasoit is a statue by the American sculptor Cyrus Edwin Dallin in Plymouth, Massachusetts. It was completed in 1921 to mark the three hundredth anniversary of the Pilgrims' landing. The sculpture is meant to represent the Pokanoket leader Massasoit welcoming the Pilgrims on the occasion of the first Thanksgiving.

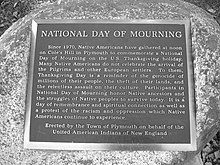

Several replicas of the statue exist across the United States, including numerous small-scale souvenir reproductions.[1] Since 1970, the statue has been the site of the National Day of Mourning, a Native American protest on Thanksgiving Day.[2]

History

[edit]

The Improved Order of Red Men fraternal organization commissioned the statue for the 1921 Pilgrim Tercentenary. Despite the group's name, they only allowed white male members at that time.[3] Massasoit's last surviving relative, Wootonekanuske, was invited to the statue's unveiling.[4] The statue sits atop Cole's Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, across from Plymouth Rock.[5] Historian Lis Blee criticized it for reflecting settler colonialism.[6]

An annual protest occurs at the statue on Thanksgiving Day in order to reclaim the space for Native Americans.[7] The National Day of Mourning began in 1970 and the United American Indians of New England continues the event to correct historical inaccuracies around the holiday and to raise awareness for Indigenous issues.[2] The Town of Plymouth later added a plaque near the statue to acknowledge the annual tradition.[8]

Replicas

[edit]Replicas of the statue are located at:

- Statue of Massasoit (Salt Lake City), in the Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City. Dallin, a Utah native, donated the cast to the State of Utah a year after the original statue was erected.[9]

- Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah[10]

- The Dayton Art Institute in Dayton, Ohio[11]

- Mill Creek Park in Kansas City, Missouri

-

The statue at the Utah State Capitol

See also

[edit]

- Pilgrim Tercentenary half dollar

- List of sculptures by Cyrus Dallin in Massachusetts

- List of Improved Order of Red Men buildings and structures

References

[edit]- ^ Blee, Lisa; O'Brien, Jean (2019). Monumental Mobility. UNC Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-4839-2.

- ^ a b Hill, Jessica (November 19, 2020). "Not all Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. Find out why". Cape Cod Times. Hyannis, Massachusetts: Gannett. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Deloria, Philip J. (1998). Playing Indian. Yale University Press. pp. 59–65.

- ^ Museum, Mattapoisett (2021-11-26). "The Last of Massasoit's Line". Mattapoisett Museum. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Sargent, Mark L. (December 1993). "The Encounter on Cole's Hill: Cyrus Dallin's "Massasoit" and "Bradford"". Journal of American Studies. 27 (3): 399–408. doi:10.1017/S0021875800032096. ISSN 1469-5154.

- ^ "Pieces of history or ugly reminders of injustice? Historians discuss monuments' meaning over time". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. 2020-11-17. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (1999). Lies Across America: What Our Historic Markers and Monuments Get Wrong. New York: The New Press. pp. 144–147. ISBN 0-684-87067-3.

- ^ Jarzombek, Mark (February 2021). "The "Indianized" Landscape of Massachusetts". Places Journal. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ "Chief Massasoit | Utah State Capitol". utahstatecapitol.utah.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Writer, NewsNet Staff (2002-02-04). "Indian statue a welcoming symbol". The Daily Universe. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Brockman, Eric (2021-02-26). "Chief Massasoit". Dayton Art Institute. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- 1921 sculptures

- Statues in Massachusetts

- Buildings and structures in Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Sculptures of men in Massachusetts

- Plymouth Colony

- Sculptures of Native Americans in Massachusetts

- Works by Cyrus Edwin Dallin

- 1921 establishments in Massachusetts

- Thanksgiving (United States)

- Improved Order of Red Men buildings and structures

- 1970 establishments in Massachusetts

- Protests in Massachusetts

- Annual events in Massachusetts

- Massachusetts sculpture stubs

- Sculptures of Native Americans in Ohio

- Sculptures of Native Americans in Utah