Marshall Holloway

Marshall Holloway | |

|---|---|

Marshall G. Holloway | |

| Born | November 23, 1912 |

| Died | June 18, 1991 (aged 78) |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of Florida Cornell University |

| Known for | Hydrogen bomb |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Nuclear physics |

| Institutions | Los Alamos National Laboratory MIT Lincoln Laboratory |

| Thesis | Range and Specific Ionization of Alpha Particles (1938) |

Marshall Glecker Holloway (November 23, 1912 – June 18, 1991) was an American physicist who worked at the Los Alamos Laboratory during and after World War II. He was its representative, and the deputy scientific director, at the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific in July 1946. Holloway became the head of the Laboratory's W Division, responsible for new weapons development. In September 1952 he was charged with designing, building and testing a thermonuclear weapon, popularly known as a hydrogen bomb. This culminated in the Ivy Mike test in November of that year.

Early life

[edit]Marshall Glecker Holloway was born in Oklahoma, on November 23, 1912,[1] but his family moved to Florida when he was young.[2][3] He graduated from Haines City High School,[4] and entered the University of Florida, which awarded him a Bachelor of Science in education in 1933,[5] and a Master of Science degree in physics in 1935.[2] He went on to Cornell University, where he wrote his Doctor of Philosophy thesis on the Range and Specific Ionization of Alpha Particles.[6][7]

Holloway married Wilma Schamel, who worked in the Medical Office at Cornell as a medical technologist, on August 22, 1938. During a picnic at Taughannock Falls on June 3, 1940, she and a graduate student, Henry S. Birnbaum, drowned while trying to rescue two women in the water. The women were subsequently rescued by Jean Doe Bacher, the wife of physicist Robert Bacher, and Helen Hecht, a graduate student, but the bodies of Wilma and Birnbaum had to be retrieved with grappling hooks two days later.[8][9]

World War II

[edit]

In 1942, Holloway arrived at Purdue University on a secret assignment from the Manhattan Project. His task was to modify the cyclotron there to help the group there, which included L.D. P. King and Raemer Schreiber and some graduate students, measure the cross section of the fusion of a deuterium nucleus, when bombarded with a tritium nucleus to form a 4

2He nucleus (alpha particle), and the cross section of a deuterium-tritium interaction to form 3

2He. These calculations were for evaluating the feasibility of Edward Teller's thermonuclear "Super bomb", and the resulting reports would remain classified for many years.[10]

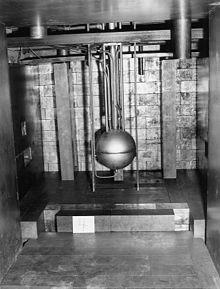

The fusion cross section calculations were finished by September 1943, and the Purdue group moved to the Los Alamos Laboratory, where most of them, including Holloway, worked on the Water Boiler, an aqueous homogeneous reactor that was intended for use as a laboratory instrument to test critical mass calculations and the effect of various tamper materials. The Water Boiler group was headed by Donald W. Kerst from the University of Illinois, and the group designed and built the Water Boiler, which achieved its criticality in May 1944 under the control of Enrico Fermi, after one final addition of uranium enriched to 14% uranium 235.[11] It was the world's third reactor[12] but the first reactor to use enriched uranium as a fuel, using most of the world's supply at the time, and the first to use liquid nuclear fuel in the form of soluble uranium sulfate dissolved in water.[13]

Holloway studied the safety of the Little Boy bomb, particularly what would happen if the active material became immersed in water.[14] He was also involved in experiments to measure the critical mass of plutonium. These proved hazardous, taking the lives of Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin after the war.[15] Holloway was part of Robert Bacher's "pit team" that assembled the Gadget for the Trinity nuclear test, and he helped Bacher fabricate the plutonium hemispheres of the Nagasaki Fat Man bomb.[16]

Later life

[edit]Holloway remained at Los Alamos after the war ended in 1945. He was its representative, and the deputy scientific director, at the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific in July 1946, when atomic bombs were tested against an array of warships.[17] Holloway became the head of the Laboratory's W Division, responsible for new weapons development.[18]

The Los Alamos National Laboratory had continued research into fusion weapons for many years after Holloway's work in 1942 and 1943,[19] and in 1951 the Atomic Energy Commission, which had replaced the Manhattan Project in 1947,[20] ordered the Laboratory to proceed with designing, building and testing a thermonuclear weapon, popularly known as a hydrogen bomb. Laboratory director Norris Bradbury placed Holloway in charge of the hydrogen bomb program.[21]

Although Holloway had a well-earned reputation for his administrative ability, Bradbury's decision to put him in charge was not popular, especially with Edward Teller. The two men had clashed a number of times over a number of different issues. Holloway's appointment was therefore "like waving a red flag in front of a bull".[22] Teller wrote that:

Bradbury could not have appointed anyone who would have slowed the work on the programme more effectively, nor anyone with whom I would have found it more frustrating to work. Norris had announced, in effect, that he did not care whether I worked on the project or not.[23]

Teller left the project on September 17, 1952, just a week after the announcement of Holloway's appointment. Nor was Teller the only one who chafed under Holloway's leadership style. Before the Ivy Mike test, Wallace Leland and Harold Agnew put a shark in Holloway's bed.[23][24][25] "He never said anything," Agnew recalled, "but after that he was much more collegial."[23][25]

The Ivy Mike test on November 1, 1952 was a complete success, but it was not a weapon so much as an experiment to verify the Teller and Stanislaw Ulam's design. Years of work was still required to produce a usable weapon.[21]

In 1955, Holloway left the Los Alamos National Laboratory for the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, where he worked on air defense projects. In 1957 he became head of the Nuclear Products-ERCO Division of ACF Industries. He was vice president of Budd Company from 1967 to 1969, when he retired to live in Jupiter, Florida, Holloway and his wife Harriet subsequently moved to Winter Haven, Florida, where his son Jerry, a retired United States Air Force officer, lived.[21] Holloway died there on June 18, 1991.[2]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hall 2008, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Schreiber 1993, p. 73.

- ^ Schreiber 1993, p. 259.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Inductees". Polk County Public School. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Bulletin of the Graduate School with Announcements for the Year 1932–1933". The University Record of the University of Florida. 27: 728. 1933. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Range and specific ionization of alpha particles". Cornell University. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ Holloway, M. G.; Livingston, Stanley (July 1938). "Range and Specific Ionization of Alpha-Particles". Physical Review. 54 (1). American Physical Society: 18–37. Bibcode:1938PhRv...54...18H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.54.18.

- ^ "Grapplers Recover Bodies of Two in Taughannock Pool" (PDF). Star-Gazette. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "On the Campus and Down the Hill" (PDF). Cornell Alumni News. 43 (16): 219. January 30, 1941. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "A History of Physics at Purdue: The War Period (1941–1945)". Purdue University. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Bunker, Merle E. (1983). "Early Reactors From Fermi's Water Boiler to Novel Power Prototypes" (PDF). Los Alamos Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory: 124–131.

- ^ Bunker 1983, p. 124.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 199–203.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 258.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 330–333, 367–369.

- ^ Schreiber 1993, p. 74.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1962, p. 529.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1962, p. 133.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1962, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Schreiber 1993, p. 75.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1962, p. 556.

- ^ a b c Goodchild 2004, p. 191.

- ^ "Harold Agnew's Interview (1994)". Manhattan Project Voices. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1995, p. 501.

References

[edit]- Goodchild, Peter (2004). Edward Teller: the Real Dr. Strangelove. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01669-9.

- Hall, Carl W. (2008). A Biographical Dictionary of People in Engineering: from earliest records until 2000. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-459-0.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1962). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- Schreiber, Raemer (1993). "Marshall G. Holloway". Memorial Tributes. 6. National Academy of Engineering: 72–77.