Marmaris

Marmaris | |

|---|---|

District and municipality | |

Marmaris harbour | |

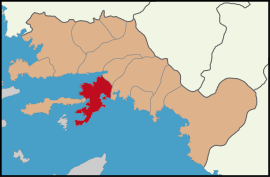

Map showing Marmaris District in Muğla Province | |

| Coordinates: 36°51′N 28°16′E / 36.850°N 28.267°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Muğla |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Acar Ünlü (CHP) |

| Area | 906 km2 (350 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 97,818 |

| • Density | 110/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 48700 |

| Area code | 0252 |

| Website | www |

Marmaris (Turkish pronunciation: [ˈmaɾmaɾis]) is a municipality and district of Muğla Province, Turkey.[2] Its area is 906 km2,[3] and its population is 97,818 (2022).[1] It is a port city and tourist resort on the Mediterranean coast, along the shoreline of the Turkish Riviera.

Although Marmaris is known for its honey, its main source of income is international tourism. It is located between two intersecting sets of mountains by the sea, though following a construction boom in the 1980s, little is left of the sleepy fishing village that Marmaris was until the late 20th century.

As an adjunct to the tourism industry, Marmaris is also a centre for sailing and diving, possessing two major and several smaller marinas. It is a popular wintering location for hundreds of cruising boaters.

Dalaman Airport is an hour's drive to the east.

Ferries operate from Marmaris to Rhodes and Symi in Greece.[4]

Etymology

[edit]During the period of the Beylik of Menteşe; the city became known as Marmaris, a name derived from the Greek màrmaron (marble; Turkish: mermer), in reference to the rich marble deposits in the region, and the prominent role of the city's port in the marble trade.

History

[edit]

Antiquity

[edit]It is not certain when Marmaris was founded but in the 6th century BC the site was known as Physkos (Ancient Greek: Φύσκος or Φοῦσκα, Phouska) in Greek, also Latinised as Physcus. It was in a part of Caria that belonged to Rhodes and contained a magnificent harbour and a grove sacred to Leto.[5][6]

According to the historian Herodotus, there had been a castle on the site since 3000 BC.[citation needed] The area eventually came under the control of the Persian Empire. In 334 BC, Caria was invaded by Alexander the Great and Physkos Castle was besieged.[citation needed] The town's 600 inhabitants realised that they had no chance against the invading army and burned their valuables in the castle before escaping to the hills. Aware of the strategic value of the castle, the invaders repaired the destroyed sections to house a few hundred soldiers before the main army returned home.[citation needed]

Ottoman period

[edit]

In the later Middle Ages, Marmaris formed part of the Beylik of Menteşe.[citation needed] Then In the mid-fifteenth century, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror conquered and united the various tribes and kingdoms of Anatolia and the Balkans, and acquired Constantinople. The Knights of St. John, based in Rhodes, had fought the Ottoman Empire for many years and managed to withstand the onslaughts of Mehmed II too.[citation needed] When Suleiman the Magnificent set out to conquer Rhodes, Marmaris served as a base for the Ottoman navy; Marmaris Castle was rebuilt from scratch in 1522 to accommodate an Ottoman army garrison.[citation needed]

In 1798, Admiral Nelson assembled his fleet in the harbour at Marmaris before setting sail for Egypt and the Battle of the Nile which put an end to Napoleon's ambitions in the Mediterranean.[7]

In 1801, a British force of 120 ships under Admiral Keith and 14,000 troops under General Abercromby anchored in the bay for eight weeks, using the time to train and resupply ready their mission to end the French campaign in Egypt and Syria.[8]

Modern times

[edit]Throughout Ottoman rule, Marmaris retained its majority Greek population up until the end of World War I. In the aftermath of the 1919–1922 Greco-Turkish War and the subsequent population exchange, the majority Greek population of Marmaris left for Greece and the town was settled by Turkish migrants from the Balkans. The two Fethiye earthquakes of 1957 almost completely destroyed the city. Only the castle and the historic buildings surrounding it were left undamaged.[citation needed]

Renovation work on the castle started in 1979. Under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, it was converted into a museum with seven galleries, the largest of them used as an exhibition hall. The courtyard is full of seasonal flowers. Built at the same time as the castle, there is also a small Ottoman caravanserai built by Süleyman's mother Ayşe Hafsa Sultan in the bazaar.[citation needed]

There were many forest fires in the early 2020s.[9]

Tourism

[edit]Marmaris is now a major package-holiday destination popular in particular with British visitors. Although adjacent İçmeler is theoretically a separate resort, these days the two more or less run into each other.

Most visitors to Marmaris come for the beaches and watersports. There are also popular cruises that take in islands in the surrounding bay, including Sedir Island (Turkish: Sedir Adası), commonly known as Cleopatra's Island, which is famous for its soft, white - and now protected - sand. Summer visitors can also take day trips to the Greek islands of Symi and Rhodes.

Archaeology

[edit]In 2018, archaeologists discovered the 2300 year-old pyramid-shaped tomb of the ancient Greek boxer Diagoras near the city of Marmaris. The following words were inscribed on it in Greek: "I will be vigilant at the very top so as to ensure that no coward can come and destroy this grave,"[10] The structure had been believed to be the grave of a saint and was visited by locals seeking answers to their prayers, but once it was realised that it was not a holy site, the mausoleum was looted.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][excessive citations]

Natural history

[edit]

Nimara Cave is located at the highest point of Heaven Island near Marmaris.[18] Since ancient times, it was used as a place of worship. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, human presence in the cave dated back to 3000 BC but excavations carried out by the Municipality of Marmaris in 2007 pushed this back by almost 12,000 years.[19] Research conducted in the cave revealed the existence of a cult of the Mother Goddess Leto, the mother of God Apollo and Goddess Artemis, in the ancient city of Physkos. Worship took place around the main rock which is surrounded by stone altars in a semi-circle raised about 30 cm from the ground. Offerings in the form of cremations, glass beads, terracotta, and sculptures of Leto were placed on these elevated stones. The cave was also used during the Roman period.

Nimara Cave was declared a protected area in 1999. It shelters trogloxene butterflies, identical to those living in Fethiye's Butterfly Valley (Turkish: Kelebekler Vadisi).[20]

The Marmaris peninsula is the westernmost habitat for Tulipa armena, which normally grows in Eastern Turkey, Iran, and Transcaucasia at much higher altitudes.[21] The plants may have been introduced during the Ottoman period.

Composition

[edit]There are 25 neighbourhoods in Marmaris District:[22]

Climate

[edit]

Marmaris has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) characterised by hot dry summers and mild rainy winters. Showers and rain are very unlikely between May and October. Summers are hot and dry, and temperatures are especially high during the heatwaves in July and August. Temperatures start to cool in September and October is still warm and bright, though with spells of rain. Winter is the rainy season, with most precipitation falling after November. Annual average rainfall is 1,257 millimetres (49.488 in) and heavy cloudbursts can cause flash floods in flood prone areas.[20] Winter temperatures are usually mild.

| Climate data for Marmaris (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

42.2 (108.0) |

43.1 (109.6) |

45.5 (113.9) |

40.7 (105.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

45.5 (113.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 255.98 (10.08) |

178.92 (7.04) |

125.74 (4.95) |

73.3 (2.89) |

29.04 (1.14) |

6.38 (0.25) |

5.6 (0.22) |

0.76 (0.03) |

22.1 (0.87) |

87.92 (3.46) |

182.3 (7.18) |

289.01 (11.38) |

1,257.05 (49.49) |

| Average rainy days | 11.4 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 11.2 | 68 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 127.1 | 137.2 | 192.2 | 222 | 285.2 | 324 | 344.1 | 328.6 | 273 | 217 | 144 | 111.6 | 2,706 |

| Source: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

Sports

[edit]The Final Four matches of the 2013 Men's European Volleyball League were held in the Amiral Orhan Aydın Sports Hall in Marmaris from July 13 to 14,.[24]

The Presidential Cycling Tour of Turkey (Turkish: Cumhurbaşkanlığı Bisiklet Turu) is a professional road bicycle racing stage race held each spring.

Every year in late October Marmaris hosts a regatta attracting domestic and international boats and crews.

International relations

[edit]Twin towns/sister cities

[edit]Marmaris is twinned with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Büyükşehir İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Sea Dreams - Ferry Booking, timetables and tickets". www.directferries.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, xiv; Stadiasmus Maris Magni § 245; Ptol., Geography 5.2.11.

- ^

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Physcus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Physcus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- ^ "Cornucopia Magazine: A Connoisseur's Guide to Marmaris & Bozburun Peninsula". www.cornucopia.net. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Mackesy, Piers (1995). British Victory in Egypt, 1801: The End of Napoleon's Conquest. p. 16.

- ^ "Forest fire ravages 25 hectares in southwestern Turkey". bianet.org. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ "Turkish locals stunned to find out sacred tomb belongs to ancient Greek boxer". Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Turkish locals stunned to find out sacred tomb belongs to ancient Greek boxer". Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Smith, John. "Turkey 'Shrine' Turns Out to be Tomb of Ancient Greek Boxer | Greek Reporter Europe". Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ "Yıllarca türbe sanıldı; mozole çıktı". www.trthaber.com. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ "Shrine in Turkey uncovered as tomb of ancient Greek boxer | Neos Kosmos". English Edition. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ TM (21 May 2018). "Previous holy site in Turkey's Marmaris revealed to be tomb of Greek boxer - Turkish Minute". Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ Team, G. C. T. "2,300 year old shrine in Turkey turns out to be tomb of ancient Greek Boxer Diagoras". Greek City Times. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ "Aegean villagers mistook Greek boxer's tomb for Islamic holy site, archaeologists discover". Ahval. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ "Marmaris Heaven Island". Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Nimara Cave, Marmaris". Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Climate of Marmaris". Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Anna Pavord, The Tulip (London, Bloomsbury 1999) 289

- ^ Mahalle, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Marmaris". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "CEV Avrupa Ligi eşleşmeleri bell oldu". Hürriyet Spor (in Turkish). 2013-07-09. Retrieved 2013-07-14.

- ^ "MARTAB: "Kardeş şehir Fürth'de Marmaris Meydanı"". Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Belediyesi, Marmaris. "Marmaris Belediyesi Resmi Web Sitesi". www.marmaris.bel.tr. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "MARTAB: "Marmaris - Ordu kardeş şehir"". Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Municipality of Ashkelon: "ערים תאומות לאשקלון "". Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ^ "Дзержинский О городе" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

External links

[edit] Marmaris travel guide from Wikivoyage

Marmaris travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Marmaris

- Marmaris District

- Turkish Riviera

- National parks of Turkey

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Turkey

- Populated places in Muğla Province

- Tourist attractions in Muğla Province

- Populated coastal places in Turkey

- Districts of Muğla Province

- Metropolitan district municipalities in Turkey

- Ancient Greek tombs

- Greek colonies in Caria